Fiction in the United States

Institution: Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Literature by American Jewish women reflects the changing issues facing writers who work to define their identities as Americans, Jews, and women. Affluent eighteenth- and nineteenth-century writers tended to play up the commonalities between Judaic and Western/Christian traditions. As Eastern European immigration increased the number of Jews in America in the nineteenth century, many first- and second-generation authors depicted the Jewish immigrant experience and how women struggled with the competing pulls of American and Jewish civilizations. In contrast, other authors wrote as self-declared citizens of the world, devoting little space to their religious/ethnic heritage. In the mid-twentieth century, female writers responded to the misogynist stereotypes of Jewish women flourishing in fiction by Jewish men. In the late twentieth century, a significant trend in writing by American Jewish women was a dramatic turn toward Jewish subjects, characters, and themes; during the past few decades a significant group of female writers have focused on the American Jewish experience from the inside, exploring the intersection between gender/ethnic/religious identity.

Literature by American Jewish women reflects historical trends in American Jewish life and indicates the changing issues facing writers who worked to position themselves as Americans, Jews, and women. Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century writers descending from affluent Descendants of the Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal before the explusion of 1492; primarily Jews of N. Africa, Italy, the Middle East and the Balkans.Sephardic and German families tended to portray Jews and Judaism though a Judeo-Christian lens, playing up the commonalities between Judaic and Western/Christian traditions. As Eastern European immigrants exponentially increased the number of Jews in American cities, many first- and second-generation authors depicted the distinctive Jewish immigrant experience and the ways in which women struggled with the competing pulls of American and Jewish civilizations. In contrast, other authors, who identified with socialist or secular, international intellectual circles, wrote from a virtually deracinated vantage point, self-declared citizens of the world, devoting little space to their religious or ethnic heritage; some wrote closeted, encoded stories of the American Jewish minority situation, using their own experiences of Jewish marginality to inform their empathetic depiction of other American ethnic and religious groups. In the mid-twentieth century, female writers created diverse literary ways to respond to the misogynist stereotypes of Jewish women flourishing in fiction by Jewish men. In the late twentieth century, a significant trend in writing by American Jewish women was a dramatic turn toward more particularistic Jewish subjects, characters, and themes; while some American Jewish women writers were only marginally interested in Judaic materials, during the last decades of the century an increasingly significant group of female writers focused directly on the American Jewish experience from the inside, many of them exploring the intersection between gender and ethnic and religious identity.

Finding Commonalities: Literary Women Prior to 1880

Literature that emphasizes the perceived moral and spiritual similarities between Judaism and Christianity is common among Jewish women whose families came to the United States when Jews comprised a gradually increasing but still extremely small American religious minority, prior to the mass immigrations of Jews from 1880 to 1924. Descended from wealthy, aristocratic Sephardic families who had participated in the formative decades of the country or from German Jewish families who had come to the United States and established themselves financially and socially during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, these cultivated middle- and upper-class American Jewish women produced primarily poetry, devotional verse, hymns, and memoir-type literature, in addition to personal correspondence. From their gracious homes in well-established Jewish communities, American Jewish women writing in the early to mid-nineteenth century tended especially to conform to what they perceived as a synthesis between Christian and Jewish ideals of feminine behavior. In both religious cultures they felt they saw women placed firmly in the domestic realm and in the extended domesticity of communal good works.

One important prototype of the issues concerning early literary Jewish women is provided by Rebecca Gratz (1781–1869), the daughter of a wealthy, socially prominent, well-traveled, entrepreneurial Philadelphia German Jewish family, whose words blend American and Jewish family ideals in an expressed devotion to domestic, communal, and religious concerns. Like other acculturated Jewish women of her time, Gratz was much influenced by the reigning cultural Christian Myth of True Womanhood, and she promoted the image of Jewish women as the equals of their Christian sisters in piety, spirituality, and literary sensitivity.

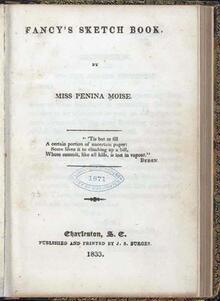

Other nineteenth-century American Jewish women writers who wrote from similar milieus reflect parallel concerns and influences. For example, Penina Moïse (1797–1880), a southern Jewish woman of Sephardic and German ancestry, wrote what is believed to be the first American book of poetry by a Jew, Fancy’s Sketch Book (1833).

A variation on the literary glorification of maternal qualities is provided by Rebekah Gumpert Hyneman (1812–1875). Her poetic output, including The Leper and Other Poems (1853), presents biblical women such as the matriarchs and female prophets and judges as representatives of the valiant but meek and gentle, angel-of-the-hearth type of woman.

Southern writers added regional patriotism to their other American attributes. Posthumously published verses by Octavia Harby Moses (1823–1904), mother of seventeen children, fourteen of whom survived, deal primarily with feminine responsibilities, family life, and praise of her “native” Confederate “beautiful land” of South Carolina. Rachel Mordecai Lazarus (1788–1838), who began her professional career by teaching in her father’s academy for young ladies in Virginia, wrote to non-Jewish novelist Maria Edgeworth complaining that Edgeworth’s character Mordecai in the novel The Absentee (1812) was based on a negative Jewish stereotype. From her vantage point in North Carolina, Lazarus wrote glowingly about “the spirit of unity and benevolence” that animated the relationship between Jews and non-Jews in antebellum Wilmington, although she did note that some non-Jews seemed to feel some “regret” at her religious persuasion (Lichtenstein, p. 100).

As increasing numbers of Jews began to arrive at America’s shores during the second half of the nineteenth century, American Jews—and writing Jewish women—expressed their awareness of seemingly growing levels of conflict between Jews and non-Jews, including overt antisemitism. Hostility to Jews evoked two responses in female Jewish authors: (1) to defend the Jewish “race,” and/or (2) to rid fellow Jews and Jewesses of “undesirable” qualities, as defined by Christian culture. In essays, poetry, correspondence, and the occasional piece of fiction, Jewish women writing in the later decades of the nineteenth century turned their discomfort with Christian anti-Jewish feeling both inward and outward. Still influenced by societal preferences for the domestic angel, they were less able than the women who preceded them to assume serene harmony between Christian and Jewish persons and value systems.

Emma Lazarus (1849–1887), the most talented and renowned of American Jewish female writers emerging from the cocoon of upper-class respectability into creative interaction with a changing world, began her career rather removed intellectually from her Jewish heritage, declaring herself to be a transcendentalist and a humanist. As the years passed, however, several factors contributed to Lazarus’s growing intellectual fascination with Jewish history and the fate of Jews worldwide, including some personal interactions with anti-Semites, the much-publicized vulnerability and suffering of Jews in pogrom-afflicted Europe and in new American immigrant communities, and literary catalysts such as Heine’s Jewishly conscious writings. For Lazarus, the creative rediscovery of the Jews was a passage into peoplehood and ethnic responsibility, rather than an overtly spiritual journey. This preference marked Lazarus not only as reflective of her own assimilated class, but also powerfully predictive of the secularized Jews who would dominate the American scene half a century later, with their cult of sacred civic survival.

Acculturation Through Writing During the Immigrant Years

Writer Mary Antin (1881-1949).

Institution:The Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives, Cincinnati, OH, and the New York Public Library.

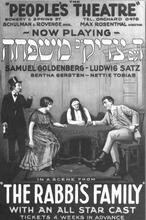

A different order of personal reinvention faced the large numbers of European women who immigrated to the United States from 1880 to 1924, and their literature illustrates very different attitudes and concerns. Jewish immigrants and their children found themselves in an environment where few traditional Jewish values were salient. Society was often turned upside down, as formerly middle-class, well-educated families found themselves plunged into abject poverty, while formerly impoverished and ignorant émigrés became entrepreneurial successes. Although immigrant women and men came to the New World hoping for comfort and opportunity, many found confusion, poverty, and exploitation instead. As their stories, novels, and letters indicate, life for immigrant women was especially difficult. Relationships between husbands and wives, and between parents and children, were often disrupted. Despite the American preference for the full-time “true woman” homemaker mother, few families were able to survive on the earnings of the husband alone, and both girls and married women worked long hours. Later immigrants provided the major workforce in the mushrooming garment industry, with girls typically working in the factories and married women doing piecework at home. Many immigrant women felt confused and almost powerless in this strange new society.

While American-born aristocrats writing before the mass immigrations conflated American and Jewish cultures into a comforting hybrid, first- and second-generation American Jewish women writers often made themselves over in their writings, creating personal histories only loosely based on the actual facts of their lives, which dramatized the transformative struggle of the immigrant experience. Mary Antin (1881–1949) and Anzia Yezierska (c. 1885–1970) are especially illustrative of this tendency, but a number of lesser-known women writers of this period also follow the pattern. For such writers, Jewish societies became a literary counterpoint to mainstream American culture; they pictured themselves as heroic women negotiating between conflicting demands.

Mary Antin’s memoir, The Promised Land (1912), was read for years as a factual description of the experiences of a young immigrant who traveled from pogroms in Polotsk to higher culture in Boston. Antin tells a mostly happy story, glorifying the process through which immigrants who would have had only narrow scope in their countries of origin are emancipated and joyously encounter the opportunities of America’s wide world. Later readers, deconstructing Antin’s sanitized description, have noted that her own life demonstrated a far more rocky interaction between Jewish and American traditions.

Anzia Yezierska’s memoir, Red Ribbon on a White Horse (1950), diverged in different ways from the plain autobiographical facts. Yezierska used her Old World heritage to enhance her persona and to make herself seem more vivid. Yezierska builds on the Hollywood public relations hyperbole that described her as “the Cinderella of the tenements,” an impoverished young immigrant whose writing talents catapulted her into Hollywood, only to find that she was by nature too sensitive and principled for the falsehoods of this glamorous but shallow world. Like Antin, Yezierska experienced conflicts that would have been dramatic enough, had she cared to write about them: various life crises apparently precipitated nervous breakdowns, flirtations with Christian Science and Eastern spirituality, and volatile relationships with a series of American celebrities, including John Dewey (Dearborn, Love, pp. 152–157).

Jewish Women Articulating America

American-born Jewish writers were far less likely than immigrants to focus openly on the Jewish experience in their writing. Gertrude Stein (1848–1946), Edna Ferber (1885–1968), Fannie Hurst (1889–1968), Lillian Hellman (1906–1984), and others, perhaps regarding the world of Jews and Judaism as too narrow and parochial for their literary concerns, created intellectual realms in which some characters might have distinctive Jewish surnames but their Jewishness had little overt significance.

The image of a minority woman moving across ethnic lines through sexual liaisons and intermarriage is a recurring motif in many of Ferber’s works. Ethnic women are presented as doubly marginal, subjected to insider/outsider status; their affection for mainstream males is explored both as transgressive behavior that meets with punishment (Show Boat) and as a positive, supremely American melting-pot response to ethnic difference (Cimarron). Despite her virtual public silence on the subject of Jewishness during the actual war years, in her notes Ferber privately dedicates the Jewishly silent first portion of her autobiography, A Peculiar Treasure (1939): “To Adolph Hitler who made of me a better Jew and a more understanding and tolerant human being, as he has millions of other Jews, this book is dedicated in loathing and contempt.” The second half of her memoirs, A Kind of Magic (1963), deals more overtly with her Jewish childhood and later trips to Nazi death camps (Walden, pp. 72–79).

An important figure in American literary and dramatic worlds, but only marginally identified as a Jew, Lillian Hellman earned her place in history through the writing of twelve serious dramas and her memoirs, as well as her political presence.

Many second-generation American Jewish literary women of Eastern European family origin seemed to avoid overtly Jewish subjects or references. American Jewish authors writing out of the Depression depicted the social activism that was typical of many immigrant Jewish women and their daughters, but much of the proletarian fiction of such writers as Tess Slesinger (1905–1945) or Jo Sinclair has little focus on the Jewish identity of characters or Jewish subject matter.

The author of essays, fiction, and poetry, Tillie Olsen (1912-2007) wrote both of women who have lost their sense of direction and of strong women involved in socialist activities. In the compelling story “Tell Me a Riddle” (1962), one of Olsen’s few works in which the Jewish identity of her characters is salient, Olsen drew on her own familial revolutionary, antireligious background.

Women's Voices at Mid-Century

Passionate attention to social problems characterized some Jewish women writers, most successfully Grace Paley (1922-2007).

Although she published books of fiction only about once a decade, with The Little Disturbances of Man in 1959, Enormous Changes at the Last Minute in 1974, and Later the Same Day in 1985, Paley’s distinctive, elliptical short story style and deft characterizations won her a devoted audience. Much of Paley’s energy was poured into social activism and political protests, concerns that are incorporated into her stories. Faith Darwin Asbury, the frequent protagonist of Paley’s short stories, is a searching, idealistic Jewish woman, the urban daughter of two aging socialists. In the stories, Faith negotiates her destiny as she becomes a single mother to her two sons. In Paley’s fiction, Jewishness is a moral consciousness, a tone of voice, the Yiddish expressions and urban accents of relatives and friends. While Paley’s concerns are universal and she expressed what many consider to be anti-Zionist sentiments, neither she nor her characters attempted to suppress their Jewishness, and the stories convey an unselfconscious comfort level with the Jewish aspects of her life.

During the 1950s and 1960s, American Jewish female writers were creating their works of fiction in an extremely hostile environment, in which their male—and far more successful—colleagues were scornfully depicting young women whose parents were grooming them to fit into upper-middle-class American norms, as they saw them.

In the early 1970s, several young female authors emerged on the literary scene whose works provided their own, woman-oriented vantage point on societal pressures. Rejecting the image of the materialistic, libidinously timid Jewish female, Erica Jong (b. 1942) created a Jewish protagonist, Isadora Wing, who overcomes her symbolic Fear of Flying (1973) by trying to live as lustily and fearlessly as any ribald male hero of picaresque sagas. Alix Kates Shulman’s (b. 1932) novel Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen (1972) and Gail Parent’s (b. 1940) satiric Sheila Levine Is Dead and Living in New York (1972) depicted the social forces shaping and distorting the self-perceptions and behaviors of one beautiful, popular and one plain, unpopular Jewish young woman, respectively. Marge Piercy’s (b. 1936) diligent chronicle of the stormy, experimental cultural environment of the late 1960s and early 1970s insists that despite the appearance of enormous external change early in the emergence of the contemporary feminist movement, Jewish women were often deluded and denuded, left with what were in actuality Small Changes (1972).

The impact of external forces on the women portrayed in Jewish fiction evolved perceptibly from decade to decade. American Jewish women struggled with a plethora of challenges in the shifting landscape of America from the 1970s through the 1990s. The whole world was seemingly open to them—they could pursue education as far as their intellectual capacities and ambitions could take them; they could enter any vocational field; they could follow their sexual inclinations into numerous or monogamous, lesbian or heterosexual liaisons; they could combine childbearing and career, juggle or sequence the two, or avoid having children altogether; they could attain rabbinical ordination or completely estrange themselves from Jewish life. The choices were at times bewildering. American Jewish literature depicted and interpreted the battles undertaken by Jewish women in this extraordinary time of change.

Many American Jewish women writers focused on gender role redefinition, often as part of an interface between Jewish values and mores and contemporary American life-styles and demographics. A gay man’s lover and former wife both show up at his son’s Lit. "son of the commandment." A boy who has reached legal-religious maturity and is now obligated to fulfill the commandmentsbar mitzvah in Marian Thurm’s short story collection These Things Happen (1988). Linda Bayer’s (b. 1948) The Blessing and the Curse (1988) and Julie Salamon’s White Lies (1987) depict the special pressures infertility and adoption create for Jews. Jewish peoplehood, in all its permutations, attracted much literary attention. The award-winning fiction of Johanna Kaplan (b. 1948) richly and often humorously captures the flavor of urban Jewish middle-class life. In Kaplan’s work, such as Other People’s Lives (stories, 1975) and O My America (novel, 1980), conflict between Jewish-radical ideals, the more traditional historical Jewish heritage, and classical American dreams is played out alongside the conflict between several generations of American Jews. Although her characters and milieus are unselfconsciously Jewish, her fiction functions as a social critique of the 1960s New Age sensibility as well as a parody of assimilationist behavior. Roberta Silman also depicted the volatile relationships between Eastern European Jews and their assimilated offspring in books such as Somebody Else’s Child (1976), Blood Relations (1977), and Boundaries (1979).

Other authors showed how negative feelings about womanhood, and specifically Jewish womanhood, could poison the relationship between Jewish mothers and daughters. Explorations of mother-daughter relationships, already an intriguing element in earlier American Jewish fiction, emerged as a major motif in women’s mid- and late-twentieth-century novels and short stories. Some female characters were portrayed as no longer content to follow in their mothers’ footsteps, yet unsure what they wished to be instead. For some, the exploration of new paths was further complicated by anguished feelings of resentment and guilt toward the mothers they loved and hated and, at least psychologically and often physically as well, were leaving behind. In a society that often vented its dislike of Jewish women, Jewish daughters feared to be too close to their mothers because they did not wish to become like them, but they felt that in abandoning their mother’s life-styles they were adding to the burdens that had already oppressed and diminished the older women.

Vivian Gornick’s (b. 1935) memoir, Fierce Attachments (1987), focused on thwarted women who turn inward, blighting the lives of subsequent generations of women. In a pattern that recalls some of the immigrant fiction, a daughter’s entire life is lived in reaction to her mother. Obsessed by the conviction that she does not want to repeat her mother’s mistakes, the daughter never truly achieves independence from the past. Mothers can withdraw from their daughters for other reasons, as editor and novelist Daphne Merkin (b. 1954) illustrated in her novel Enchantment (1986). In Merkin’s novel, Hannah Lehman grows up in an affluent German Jewish Orthodox home on New York’s Upper West Side. In contrast with the more familiar stereotype of the “smothering” Jewish mother, Hannah feels that her mother ignores her. Her mother’s emotional withdrawal controls Hannah’s life just as surely as another mother’s direct manipulation.

Some of the most fascinating literature by American Jewish women in the 1980s and 1990s explored the dialectic of appetite and repulsion that female sexuality evokes in some men. While fascinating as a psychological phenomenon, this love-hate relationship has been the basis of profound discrimination against women at many times and in many cultures. American Jewish women often included male characters who project their own psychological ambivalence onto female physical characteristics and virtually convert normal female physiology into a type of pathology. Not infrequently, a mother internalizes restricted expectations of womanhood and passes them along to her daughter.

Lynne Sharon Schwartz (b. 1939) explored the deadening effect of bourgeois expectations for women in several pieces of fiction, especially Leaving Brooklyn (1989), an extraordinary short novel. Schwartz’s protagonist, Audrey, is a young adolescent girl with one normal eye, through which she sees the ordinary, proper world of middle-class Brooklyn, and one damaged eye, through which she glimpses a sinister world of dark impulses, sexuality, and chaotic, uncharted possibilities. The ophthalmologist hired by Audrey’s mother to cure Audrey’s wandering eye with a specialized contact lens also enters into a sexual relationship with the child. When the relationship is ended and Audrey reevaluates the Brooklyn world of her parents and their card-playing friends, she discovers that human beings—even middle-class Jewish parents—are far more complex than she had imagined: Memory plays tricks, and everyday realities shift and blur with or without a trick eye. In her parents and their friends she discovers a political liberalism that amounts to heroism in the repressive anticommunist era, and in herself she discovers an ineradicable piece of Brooklyn from which she will be forever departing.

In another response to perceived misogyny and patriarchal oppression, some Jewish authors championed lesbianism as both a physical/social orientation and as a political statement. These authors described the worldview and experiences of those Jewish women who reject male-identified gender behavior and identify primarily with other women. Fiction depicting the lives of identified Jewish lesbians, once difficult to find, began to proliferate. Some titles include Alice Bloch’s (b. 1947) The Law of Return (novel, 1983), Lesléa Newman’s (b. 1955) A Letter to Harvey Milk (stories, 1988), Jyl Lynn Felman’s (b. 1954) Hot Chicken Wings (stories, 1992), and Joan Nestle’s (b. 1940) A Restricted Country (1987). While some works were highly critical of Jewish tradition, which they perceived as hostile, much significant Jewish lesbian writing was deeply committed to Jewish peoplehood and Jewish survival, and several anthologies were largely dedicated to Jewish-content feminist and lesbian writing.

Sephardi women have had their own special relationship with patriarchal family and community systems. Many Sephardi Jewish women have stated that women in Sephardi society today have been far more cloistered and restricted in their activities than women deriving from German or Eastern European Jewish societies. Beyond the boundaries of the Sephardi community, some Sephardi Jewish women write that they endure a double discrimination—they are suspect because they are women and because they are not of Ashkenazi derivation. The characters and milieus treated by contemporary Sephardic women writers diverge from those dealt with by aristocratic women of Sephardi descent in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as well as those of Ashkenazi writers. In literature such as Gloria Kirschheimer’s “The Voyager” (1984) or “Nona: A Recollection” (1991), Ruth Knafo Setton’s “Songs from My Mother’s House” (1993) or “Street of Whores”, or Rosaly De Maios Roffman’s “Sometimes People Think: Puffin Rhapsody” (1988) or “My Japanese Lady” (1992), the reader encounters Jewish and female visions that differ from those of other Jewish societies.

An Unexpected Turn Toward Jewish Culture

In addition to the increasing consciousness of women’s issues produced by the varieties of the women’s movement, Jewish consciousness was being raised as well. Starting in the late 1960s and 1970s and continuing through the 1990s, enormous changes occurred in the Jewish literary world, in which Jewish women were full and important participants. A significant group of contemporary American Jewish writers produced an inward-turning genre of fiction that explored the individual Jew’s connection to other Jewish people, to the Jewish religion, culture, and tradition, and to the chain of Jewish history. Jewishly literate fiction flourished in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s on every level; it attracted a broader reading audience than anyone might have predicted. In women’s fiction ranging from highly serious to middlebrow to frankly pulp fiction, aspects of Jewish life that earlier in the century might have seemed to be inaccessible esoterica were transformed into exotica. Contrary to the expectations of assimilationists and the example of Jewish literature during the first half of the twentieth century, particularistic women’s Jewish fiction became a commonplace.

Among major themes that emerged in late twentieth-century American Jewish fiction focusing on women, some of the most important included: the role of the Holocaust in the identity of survivors, their children, and the broader Jewish community; Israel as a focal point of American Jewish identity and a setting for the exploration of Jewish identity; a variety of religious and cultural subgroups within Jewish life, such as Sephardi Jewish communities, ultra-Orthodox communities, and feminist groups; sexual subgroups, such as Jewish lesbians and homosexuals; gendered relationships and the tension between intellectual and sensual, personal and professional, or Jewish and humanistic agendas in the lives of contemporary American Jewish women.

Orthodox Characters, Settings, and Concerns

"I wanted to use what I was, to be what I was born to be—not to have a 'career,' but to be that straightforward obvious unmistakable animal, a writer," Cynthia Ozick once said. She has certainly achieved her goal. The winner of numerous literary awards, Cynthia Ozick is a writer par excellence, author of essays, plays, short stories and novels.

Institution: The Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives, Cincinnati, OH, www.americanjewisharchives.org and Gerard Murrell.

Characteristic of American Jewish women’s literature during the last quarter of the twentieth century is a depiction of diverse Orthodox societies and characters. This trend differs markedly from American Jewish literature of earlier periods, in which Orthodox characters tended to be cranky old men or force-feeding mothers and aunts. Orthodox Jewish characters and settings now enjoy an unprecedented and variegated focus in new American Jewish fiction. Among contemporary younger authors, Nessa Rapoport’s (b. 1953) moving first novel, Preparing for the Sabbath (1981), portrays a young woman struggling with the conflicting demands of youthful passion and spirituality, and of Orthodoxy and secularism, in both American and Israeli settings. Both the title of Allegra Goodman’s (b. 1967) first collection of short stories, Total Immersion (1989), and the themes, imagery, and subject matter of many of the stories reflect her childhood in an Orthodox family in Hawaii. Her second collection, The Family Markowitz (1996), focuses largely on the tendency of modern/liberal/traditional Jews to merge American and Jewish values and behaviors—sometimes comically—in their everyday lives. Goodman’s first novel, National Book Award finalist Kaaterskill Falls (1999), captures the inner and outer worlds of a fervently Orthodox woman: the conflict between her love of tradition and her yearning to expand her cultural horizons is set against her community’s social and religious dynamics as they summer en masse in the mountains of upstate New York.

Savagely humorous depictions of the idiosyncrasies and foibles of Orthodox environments are found in the pages of Tova Reich’s (b. 1942) Mara: A Novel (1978), which knowingly depicts wealthy contemporary Orthodox New Yorkers, and The Master of the Return (1988), which wickedly satirizes the spiritual searchings of a motley collection of ba’alei teshuvah [born-again Jews], who have gathered under the aegis of the Breslover Hasidic group in Israel.

The focus on Orthodox Judaism is a reflection of the interest Orthodox societies evoked among some seemingly secularized American Jews. The story of such unlikely Orthophilism is found in Anne Roiphe’s (b. 1935) popular and much-excerpted Lovingkindness (1987), a tale of an ultra-assimilated, intermarried, and widowed feminist whose daughter becomes a devoutly Orthodox Jew, much to her mother’s initial astonishment and distress. A journey toward exploration of classical Jewish texts and ideas is found in the works of novelist and essayist Norma Rosen (b. 1925).

Another version of the trajectory in which an intellectual fascination with Judaica is followed by the writing of fiction that deals with it is found in the work of Rhoda Lerman (1936-2015). Lerman’s New York suburban, ritually observant Jewish family sent her to Sunday school only, because she was a girl. Lerman’s resulting feelings of alienation from the patriarchalism of traditional Jewish life (Satlof, pp. 197–208) were captured in her irreverent, explicit novel Call Me Ishtar (1973). However, later contact with a Hasidic rabbi led her to embark on a course of formal Jewish text study in several settings. Her novel God’s Ear (1989), based in part on her Hasidic mentor, features a protagonist who is first a Hasidic rabbi, then an affluent insurance salesman, and finally once again a rabbi and spiritualist in unlikely Kansas.

This fascination with Orthodox settings extended to mystery novels and to popular fiction as well. For example, Faye Kellerman’s homicide detective hero meets the widow of a kollel yeshiva student in her mystery The Ritual Bath (1986); their relationship continues, with the detective serendipitously discovering in Sacred and Profane (1987) that he has Jewish origins and is thus an appropriate romantic interest for the Orthodox widow. The series proved so popular that this seemingly odd couple went on to numerous adventures in subsequent books. Similarly, Naomi Ragen’s popular novel Jepthe’s Daughter (1989) brought a beautiful young Orthodox woman from affluent America to the extremism of a cloistered Jerusalem neighborhood in a disastrous marriage to a rigid and unpleasant Hasidic Jew; she escapes the nightmare by falling in love with a seemingly gentile gentleman who turns out to have had a Jewish mother. Romances especially have mined the exotic settings offered by biblical, Eastern European, Sephardic, and Orthodox worlds, often in combination with American Jewish settings. In scores of popular romances by authors such as Cynthia Freeman, Belva Plain, Julie Ellis (b. 1933) and Iris Rainer Dart, landmarks of Jewish history previously relegated to textbooks became plot devices in the pages of glossy-covered novels. As expected, their female protagonists are almost always breathtakingly beautiful and, no matter how agonizing their experiences, almost always achieve the romantic and material successes that are a sine qua non of the genre. However, unlike such heroic characters in the past, these beautiful protagonists are often identifiably, proudly Jewish and achieve their goals not through the ministrations of a handsome and mysterious gentleman but through their own intelligent, energetic efforts. The image of the Jewish woman in contemporary American Jewish literature was affected even at the most basic, grass-roots level.

Emblematic of the new Jewish American women’s literature at its highest level are the novels, short stories, and essays of Cynthia Ozick (b. 1928). Ozick’s signature preoccupation is the conflict between the Jewish intellectual, spiritual, and cultural tradition, on one hand, and the Hellenistic sweep of artistic creativity and secular Western humanism, on the other hand. The conflict between art and Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah is no mere intellectual game for Ozick; she expresses it in numerous stories and novels as a deep, ongoing struggle.

Like Ozick, Rebecca Goldstein (b. 1950) demonstrates in her short stories and novels a thorough familiarity with diverse issues in Jewish society and in traditional Jewish life. Her work explores topics as different as the respective difficulties experienced by children of Holocaust survivors and by urban New York Jews in preppy suburban Princeton. Goldstein’s protagonist in The Mind-Body Problem (1983) is a “beautiful, brainy” young woman, Renee Feuer, who grew up in a strictly Orthodox home. After leaving home for college and then graduate school, Renee moves incrementally away from her training. When Renee abandons religious ritual for the study of philosophy, there is more than a little religious intensity and spiritual searching in her choice. Much to her surprise, she finds that her graduate school professors and her intellectual but Jewishly ignorant husband are at least as sexist as the Orthodox world she left. Renee comes to see her mind as the enemy that threatens her marriage. Her friend, in contrast, sees her body as the enemy that threatens her intellectual career. Even in the secular world, women are often pathologically divided, according to authors such as Goldstein. After writing several novels and short story collections not so directly focused on Jewish themes, Goldstein returned to the theme of Jewish women’s identity as women and as Jews in her multigenerational saga Mazel (1995). Goldstein captures both the warmth of the traditional Jewish home and the tragic constrictions traditional Jewish societies often impose on creative women, in prose that is moving and playful in turn.

The quandaries experienced by Goldstein’s protagonists are paradigmatic of realities in American Jewish societies, which during the final quarter of the twentieth century have seen simultaneous attenuation and intensification of Jewishness among different segments of the population. Even among those writers and readers with little interest in or knowledge of traditional Jewish texts and life-styles, fierce secularism found few voices. Instead, the hostility of earlier generations often mellowed into nostalgia, leaving Jews who once fled from the sights, sounds, and social pressures of the urban ghetto now anxious to read literature that recaptured for them scenes and experiences from their childhood and youth.

The Holocaust Reconsidered

Both Ozick and Goldstein have written powerful fiction dealing with yet another characteristic preoccupation of American Jewish women’s writing—the Holocaust and the lost communities of Eastern Europe. Ozick argues against an attempt to try to explain Jewish suffering in the Holocaust as a Christological activity. In The Shawl (1989) and The Messiah of Stockholm (1987), Ozick mourns the Holocaust destruction of European Jewish culture and portrays survivors as idiosyncratic, flawed human beings, rather than as bland or mystical symbols, at the same time making their pain and confusion palpable. Goldstein’s story “The Legacy of Raizel Kaidish” (1985) portrays a mother who tries to mold her daughter into a selfless, dispassionately altruistic saint—all in an effort to expiate her own profound moral failure within the hell of the concentration camps. Only on her deathbed does she acknowledge that she has been wrong to sacrifice her daughter’s autonomy.

The scores of Holocaust-related novels and memoirs, both autobiographical and fictional, published by women in the United States run the gamut from simply told personal tales to philosophical explorations of the meaning of evil to lightly fictionalized historical chronicles to cinematic soap operas. Norma Rosen’s Touching Evil (1969), mentioned earlier, and Susan Fromberg Schaeffer’s (b. 1941) Anya (1974) are stirring depictions of the Holocaust and its impact. Among Gloria Goldreich’s (1934) best-selling, well-researched popular historical sagas, which look backward to explore the transformation of Jewish life in American immigrant societies and then trace its progress through contemporary times, one of the most moving is her Holocaust novel, Four Days (1980).

Other recent Holocaust memoirs include Gerda Klein’s All But My Life (1995), the basis for the Emmy-winning documentary “One Survivor Remembers,” about Klein’s concentration camp ordeal and her liberation by the American soldier who became her husband, and Magda’s Daughter: A Hidden Child’s Journey Home (2003), Evi Blaikie’s story of her struggle to adapt—to new countries, religions, names and even genders (at the age of two she was smuggled from Paris to Budapest on a male cousin’s passport)—a search for identity and a “home” that has lasted a lifetime.

Feminism and Spirituality

Some feminist literature was experimental in theme, style, or content, and Jewishly spiritual in its concerns. Esther Broner’s (1930-2011) mystical fiction, A Weave of Women (1978), described a dozen women and three girls who dream of and plan for a feminist vision of utopia in Israel. Broner’s experimental style in this novel, which blends Hebrew, Yiddish, and biblical motifs within narrative, drama, and poetic forms, might be termed mythic exploration of feminist issues. A nonfiction book, The Telling (1992), deals with the creation of Jewish women’s religious rituals in the form of a feminist Lit. "order." The regimen of rituals, songs and textual readings performed in a specific order on the first two nights (in Israel, on the first night) of Passover.seder involving Broner, Gloria Steinem, Letty Cottin Pogrebin, [link to new entry on Letty Cottin Pogrebin] Bella Abzug, Phyllis Chesler, and other Jewish activists.

Another example of Jewish feminist/spiritualist writing was Kim Chernin’s (b. 1940) The Flame Bearers (1986), a historical novel depicting a sect of Jewish women devoted to a female aspect of godhead called Chochma, the Bride. Other works by the prolific Chernin include feminist-oriented and Jewishly intense essays, such as those found in Reinventing Eve (1987), her memoir, In My Mother’s House: A Daughter’s Story (1983, subsequently paralleled by a spiritual memoir, In My Father’s Garden: A Daughter’s Search for a Spiritual Life, 1996), and The Woman who Gave Birth to her Mother (1999). Chernin was among those Jewish feminists who believed that merely giving women access to male forms of Jewish worship, liturgy, and religious imagery does little for truly woman-oriented spiritual expression. Like other writers, Chernin found Israel a particularly felicitous literary setting to make contact with previous suppressed images of female divinity.

Conclusion

The literary passage from Rebecca Gratz to Rebecca Goldstein incorporates nearly two centuries of cultural change. From the pedestal of heroic, restricted, self-consciously Judeo-Christian “true” womanhood, through the dislocating crucible of mass immigration, into the passionate Americanization of the first half of the twentieth century, Jewish women’s literature preserved women’s voices. Nevertheless, for many years, Jewish female writers, doubly marginal, avoided direct literary encounters with some primary aspects of their identity; indeed, Jewish male writers also catered for decades to the predominantly non-Jewish literary establishment either by ignoring Jewish subject matter or by treating Jewish characters as a species of precocious existential or comical “others,” whose value consisted in their standing both inside and outside of and commenting on Christian or secular societies. When Jewish men did write directly about Jews, they often cast Jewish women in satirical stereotypes, deflecting cultural antisemitism onto the female of the species. However, American Jewish women’s literature of the 1980s and 1990s drew on the full, complex, often contradictory and conflicting particularisms of the female Jewish American experience and vision. The female protagonists of late twentieth-century American Jewish fiction struggled with a multiplicity of identities: They were Jewish, Americans, daughters and wives and lovers and mothers; they were moderns—they were heirs to an ancient tradition. The proliferation of Jewish women writing—and being published—as America has crossed into the twenty-first century literally speaks volumes about the preservation of women’s visions and women’s voices for the coming generations.

Antler, Joyce. America And I: Short Stories By American Jewish Women (1990).

Batker, Carol. “Fannie Hurst.” In Jewish American Women Writers: A Bio-Bibliographical And Critical Sourcebook (1994).

Blaikie, Evi. Magda’s Daughter: A Hidden Child’s Journey Home. The Helen Rose Schueur Jewish Women’s Series. New York: 2003.

Calisher, Hortense. Kissing Cousins: A Memory (1988), and “No Important Woman Writer.” In Women’s Liberation and Literature, edited by Elaine Showalter (1971).

Dearborn, Mary V. Love in the Promised Land: The Story of Anzia Yezierska (1988), and Pocahontas’s Daughters: Gender and Ethnicity in American Culture (1986).

Fishman, Sylvia Barack. “American Jewish Fiction Turns Inward.” AJYB 91 (1991).

Henderson, Bruce. “Lillian Hellman.” In Jewish American Women Writers.

Hindus, Milton. “Ethnicity and Sexuality in Gertrude Stein.” Midstream 20 (January 20, 1974).

Lichtenstein, Diane. Writing Their Nations: The Tradition of Nineteenth-Century Jewish Women Writers (1992).

Matza, Diane. Writing the Culture: Sephardic American Literature (1997).

Satlof, Claire R. “Rhoda Lerman.” In Jewish American Women Writers.

Shapiro, Ann R., Sara R. Horowitz, Ellen Schiff, and Miriyam Glazer, eds. Jewish American Women Writers: A Bio-Bibliographical and Critical Sourcebook (1994).

Wald, Alan. The New York Intellectuals: The Rise and Decline of the Anti-Stalinist Left from the 1930s to the 1980s (1987).

Walden, Daniel. “Edna Ferber.” In Jewish American Women Writers.

Weinberg, Sydney Stahl. “Longing to Learn: The Education of Jewish Immigrant Women in New York City, 1900–1934.” Journal of American Ethnic History (Spring 1989), and The World of Our Mothers: The Lives of Jewish Immigrant Women (1988).

Wilentz, Gay. “Jo Sinclair.” In Jewish American Women Writers.