Fiction, Popular in the United States

As Jewish women came to constitute a strong presence in American popular fiction, their work increasingly featured an assertively Jewish component combined with the construction of strong women characters. This writing expressed a wide mix of attitudes and writer experiences. Along with pride in Jewishness, there was ambivalence and at times self-hatred, but the wide variety of books and stories published revealed many ways to be Jewish in the contemporary world and many opportunities open to women. To the extent that this kind of writing had mass appeal, these authors spread an awareness of Jewishness into the mainstream of American popular culture. At the same time, they used the formulas of genre fiction to explore Jewish identity.

Introduction

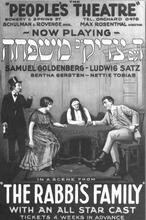

The explosion of writing by American Jewish women in the twentieth century produced not only serious fiction, poetry, essays, and autobiography but also a range of popular literature geared to pleasure reading and light entertainment. Jewish women authors experimented with many genres: regional novels, sagas, historical novels, romances, mysteries and crime fiction, science fiction, fantasy, and humor. This fiction, with its popular appeal, was often adapted to the cinema, and a number of these women authors also wrote screenplays or television scripts. Works by Jewish women appeared on best-seller lists with increasing frequency in the later decades of the twentieth century. Some of the best-selling titles did not deal directly with Jewish content, but attention to overtly Jewish themes became more and more widespread through the 1980s and 1990s.

Early Decades

Two of the early figures who achieved exceptional success and influence were Edna Ferber and Fannie Hurst, who began publishing in the 1910s and whose titles first reached the best-seller lists in the 1920s and 1930s. Each wrote more than a dozen novels, as well as short stories, and their fiction served as the basis for successful motion pictures.

Edna Ferber (1885–1968) was the first Jewish American woman to win the Pulitzer Prize (1925), for the novel So Big (1924). Ferber is famous for her regional novels, which stress the history, attitudes, local color, and typical characters of various parts of the United States. Her best-known books include Show Boat (1926), which deals with life on the Mississippi River; Cimarron (1930), which focuses on the Oklahoma territory; and Giant (1952), which portrays Texas ranchers and oil tycoons. While a number of Jewish characters enter these fictions peripherally, they are central to Ferber’s Fanny Herself (1917), a semiautobiographical novel about a young girl growing up in the Midwest. Fanny strikes out on her own to make a spectacularly successful career in business. After a period of trying to deny her Jewishness, this character comes to take pride in her identity. Indeed, she becomes convinced that Jews possess special talents and sensibilities because of the suffering they have endured over the ages. Here, as in other novels by Ferber, a strong female character helps to build America as she herself achieves the American dream of success.

Fannie Hurst (1889–1968) expressed more ambivalent feelings about Jewish identity than did Ferber, and she treated the topic less openly in her fiction. Notable exceptions are the novel Family (1960), which deals with intermarriage, and Humoresque (1919), short vignettes that deal with Jewish characters. Hurst wrote frequently on gender politics, highlighting the constricting roles that women in her day faced in marriage and domestic life, as well as the challenges and inequities they met in the labor force. Though Hurst’s own success brought her affluence and connections with high society—Hurst was said to be the highest-paid short-story writer of her time, and she earned considerable income from movie rights—she often wrote about ordinary people and expressed solidarity with the poor. Her best-known novel, Imitation of Life (1933), recounts the life of a single mother who makes a fortune by opening a chain of restaurants. Hollywood produced two movie versions of this tale.

Rebellion Against Stereotypes

During the middle decades of the twentieth century, the image of Jewish women in popular fiction was dominated by negative stereotypes. The most prevalent figures were the Jewish mother, seen as an overly anxious, stifling parent who lives through her children’s accomplishments, and the JAP—the Jewish American Princess—a spoiled, self-absorbed, materialistic character who is at once shallow and sexually frigid. The assumption underlying this denigrating image of young women is the idea that their entire goal in life is marriage for the sake of financial security. Consequently, the logic of the stereotype dictates that since these women care only about money, they withhold sexual favors until they obtain the kind of marriage that will bring them affluence. The JAP thereby comes to represent the emptiness of affluent suburban life and of the Jews as a whole, who are seen to be greedy and ostentatious social climbers.

These stereotypes took on currency in the 1950s in large measure through Herman Wouk’s novel Marjorie Morningstar (1955) and Philip Roth’s Goodbye, Columbus (1959). These images became entrenched and flourished throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Beginning in the 1970s, however, Jewish women began to challenge those stereotypes and voice opinions about their own lives and experiences. Women writers rejected the narrow roles conferred on them as Jewish daughters, wives, and mothers. Time and again in fiction, female characters present themselves as individuals with thoughts and feelings of their own who are aware of their sexuality and are unwilling to serve merely as symbols of upward mobility. Gail Parent’s Sheila Levine Is Dead and Living in New York (1972), Louise Blecher Rose’s The Launching of Barbara Fabrikant (1974) and Susan Lukas’s Fat Emily (1974) are notable for presenting protagonists who do not play the marriage game because they are not attractive enough. These novels construct funny, brash female characters who lay bare the destructiveness of social norms that place exaggerated importance on women’s appearance and do not take seriously their accomplishments. Alix Kates Shulman’s Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen (1972) features a protagonist who is beautiful and finds suitors easily, but she agonizes constantly that her looks will deteriorate as she moves past the age of twenty-five. These and other writers (Myrna Bluthe, Cousin Suzanne, 1975; Marie Brenner, Tell Me Everything, 1976; Sandra Harmon, A Girl Like Me, 1975) highlight norms of behavior for women that were often a prescription for self-hatred. That is, women who were urged to invest all of their self-esteem in their appearance were also adjured not to look Jewish, even to the point of using cosmetic surgery to reshape their noses.

These novels, as they protest against narrowly defined expectations for women, are products of the foment that gave rise to the women’s movement in the 1970s. Among the best-known texts of the period are Sue Kaufman’s Diary of a Mad Housewife (1967) and Anne Roiphe’s Up the Sandbox (1970), both of which were turned into popular films. These novels do not explicitly enter into questions of Jewishness or examine the mores and foibles of the Jewish middle class, but they are part of the same phenomenon as they protest against the strictures of domestic life for women and against submissiveness to husbands. Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying (1973) merits special mention in this regard. This novel met with enormous commercial successes (over six million copies sold) and came to be seen as emblematic of the success of the women’s movement. Jong’s protagonist-narrator, Isadora Wing, flaunts her sexuality and her enjoyment of it while also expressing clearly her ambitions for a career. She is confused about how to balance her need for men and her love life with her professional aspirations, but she is a far cry from the JAP who seeks only material security through marriage. Fear of Flying, with the celebrity it achieved, also helped redefine popular fiction. While Jong’s detractors dismissed her fiction as a contemptible phenomenon of mass culture, accusing it of positing a shallow view of life in prose marked by vulgarities and clichés, Jong’s supporters have argued that her success allowed a silent, unrecognized female majority to express itself, to question women’s roles in marriage, and to transform sexual norms previously defined by men.

In her later novel, Parachutes and Kisses (1984), Jong continues the tale of Isadora Wing, again joining a picaresque mode with a female sensibility to recount a series of sexual adventures. This novel, however, pays considerably more attention to the protagonist’s Jewishness. A now forty-year-old Isadora seeks to understand her creativity and artistic talent as assets inseparable from her Jewish roots and family heritage. Serious attention to these themes makes for an uneasy combination with the comic sexual escapades, and Parachutes and Kisses was not so well received either by critics or by the public.

Historical Novels and Family Sagas

Historical novels and family sagas have long been a staple of best-seller lists in the United States, and interest in this kind of fiction increased toward the end of the twentieth century. From the 1960s to the 1990s, judging by sales figures, the historical novel was the most popular of all genres. This trend in reading coincided with another: Whereas at mid-century, American Jewish authors commonly depicted Jews as outsiders or as universal symbols, in later decades, American Jewish fiction increasingly showed an overt interest in Jewish tradition, religion, and history. Not surprisingly, then, during the 1970s and 1980s, historical fiction and family sagas frequently became a forum for the exploration of Jewish identity. As they present a panoramic view of a family over several generations, highlighting births and deaths, love affairs, and the ways family members are swept up in historic events, such novels have shown a fascination for the Jewish past and Jewish milieus.

A most familiar scenario is that of impoverished Eastern European Jews who come to America, adjust to immigrant society, and then move on to middle-class comfort or, frequently, to fabulous wealth (in, for instance, Belva Plain’s Evergreen, 1978, and Gloria Goldreich’s Leah’s Journey, 1978). The rags-to-riches theme, a perennial favorite in the American novel and particularly prominent in light entertainment reading, here coincides with Jewish perceptions of America as a land of opportunity for immigrants. Another preoccupation of popular fiction, increasingly evident over time, is the Holocaust. Family sagas focusing on this issue often emphasize how families have dispersed—some relatives stay in Europe and meet their doom, while others make their way to America or to Israel. Carolyn Haddad’s A Mother’s Secret (1988), Marge Piercy’s Gone to Soldiers (1987), and Cynthia Freeman’s No Time for Tears (1981) suggest a strong feeling of kinship among Jews in different nations and a keen sense that “there but for the grace of God go I.” One of the most touching characters in this regard appears in Piercy’s Gone to Soldiers. A young Parisian who reaches safety and finds refuge in Ohio while her twin sister is interned in a concentration camp, Naomi is wracked by guilt over her own comfortable survival. As if by telepathy, she dreams the experiences and vicariously feels the torments that her sister undergoes far away.

Other novels have explored a variety of more exotic settings or less familiar milieus. Faye Kellerman’s historical thriller, The Quality of Mercy (1989), features converso characters in Elizabethan England who practice their religion in secret. Belva Plain’s Crescent City (1984) places its protagonist in Louisiana during the Civil War. There she faces the dilemmas of being at once a wealthy Southerner, a Jew who cannot condone slavery, and a woman who must take over the family business and intervene in politics due to personal hardships and the tragedies of the war. Julie Ellis’s East Wind (1983) takes the reader to a more remote location as it focuses on turn-of-the-century Hong Kong and highlights the small Jewish community of Chinese Jews in Kaifeng. Again, however, the unusual setting provides an opportunity to recount a plot with a familiar pattern. This novel, too, follows the major life events of a protagonist aware of the many strata in her identity, even as the author insists on images of female strength, independence, and ability to transcend stereotyped roles and limitations. The protagonist of East Wind is a Jew, a woman, and an American (though living in the East). Circumstances bring her to take full responsibility for her finances, for raising a family, and for respecting and defending her Jewish identity, even as she pursues fulfillment in passionate love.

Much of this fiction is formulaic in nature, and part of its appeal for readers is its predictability. One of the standard features of such writing is a beautiful and wealthy main character who proves brilliant in whatever endeavor she undertakes. Often unhappy in love, she nevertheless remains glamorous and overcomes all manner of adversities. Promising page-turning excitement, romance, scandal, and heartbreak, this genre offers fantasies of opulent living and melodramatic emotional highs and lows. Infused with a steady dose of tragedy, historical fiction and family sagas allow readers to identify with the rich and famous but finally not to envy them too much.

These qualities link this fiction with the romance, a related genre that focuses more closely on the life of a single protagonist and pays less attention to wide family ties or to broad historical sweep. Among the prolific writers who have produced more than a dozen such titles are Cynthia Freeman (born Bea Feinberg) and Julie Ellis. Concerned as they are with love and marriage, romances and family sagas are a natural venue for discussion of intermarriage, an important component of Freeman’s Portraits (1979), Come Pour the Wine (1980), Illusions of Love (1984), and The Last Princess (1988), as well as Ellis’s Glorious Morning (1982), The Velvet Jungle (1987), The Only Sin (1986), Loyalties (1989), and Trespassing Hearts (1992). These novels express a range of attitudes toward assimilation and antisemitic prejudice—sometimes true love prevails despite differences in religious background, sometimes the discovery of Jewish roots and connections becomes paramount in defining who is a worthy object of love—but all of this fiction creates opportunity for exploring Jewish identity through the lens of love and marriage. Tending toward clichés, contrived plots, and melodrama, this kind of writing nevertheless provides a remarkable indication of how Jewish themes and positive Jewish characters developed wide appeal for the mass market.

More in-depth attention to Judaism and to traditional customs and values animates the novels of Naomi Ragen, such as Jephthe’s Daughter (1989), Suspected adulteressSotah (1992) and The Sacrifice of Tamar (1995). Falling into a category of its own, this fiction is written by an American-born woman who has lived for many years in Jerusalem, but whose books, written in English, were at first published and distributed primarily in the United States. (Later translated into Hebrew, they achieved best-seller status in Israel.) They are of special interest, as they describe the private lives of ultra-Orthodox women, thus giving the general public entree to a milieu ordinarily inaccessible to outsiders. Drawing on some of the usual elements of the romance genre—heroic women of stunning beauty, vast wealth, passionate loves—Ragen also explores young An ultra-Orthodox Jewharedi women’s schooling, their education about sexuality and the Jewish laws of sexual purity (Ritual bathmikveh and Menstruation; the menstruant woman; ritual status of the menstruant woman.niddah), and their emotional responses to the intimacies of marriage and to family dynamics. This fiction thereby creates a striking intersection of Jewish values and secular ones. Thematically, the author condemns the emptiness, crass materialism, and selfishness of the secular world. At the same time, this highly secular genre, promising sensationalism or scandal, allows the author to explore the inner workings of a community that discourages secular reading of any sort and shuns commercial popular fiction. The result is entertainment, romance with a new slant, but also a thoughtful contrasting of worlds. Ragen uses fiction as a way to examine which Jews live out a decent and spiritually fulfilling life and which ones merely observe Jewish law without true devotion.

Mystery, Detective Fiction, and Spy Thrillers

A somewhat jarring combination of secular and religious values also characterizes the detective and crime fiction by Jewish women that came into vogue in the 1980s and 1990s. Preceded by mysteries in which Jewish topics were incidental—for example, novels by Amanda Cross (pen name of Carolyn Heilbrun), such as Death in a Tenured Position (1981), and whodunits that featured Jewish characters and milieus without a focus on Jewish identity or Judaism, such as Susan Isaacs’s Compromising Positions (1978)—women mystery writers with distinctly, assertively Jewish topics found an enthusiastic readership and gained national visibility in the late 1980s. Their commercial success led to series of novels, appearing more or less annually, centered around Jewish women private investigators or amateur sleuths. A confluence of social and literary forces enabled this development. A boom of crime fiction in all its forms took place in the 1980s, and this was a period in which women became more prominently recognized as mystery writers. In addition, as publishers turned increasingly to specialized interests and subcultures, mysteries by and about Jewish women became a highly sought specialty.

The best known of the writers in this genre is Faye Kellerman. She has produced a series of novels featuring Rina Lazarus, a beautiful, young Orthodox widow, and police detective Pete Decker: The Ritual Bath (1986), Sacred and Profane (1987), Day of Atonement (1991), Grievous Sin (1993), False Prophet (1992), Sanctuary (1994), and Prayers for the Dead (1996). Attracted by Lazarus’s charms, the gentile Decker is drawn, too, to Judaism. Together, the two solve crimes, and eventually he adopts Orthodoxy and they marry. Attention to Orthodox settings accounts in part for the popularity Kellerman achieved. This element of local color defines for Kellerman a distinctive angle on crime fiction. Rina Lazarus and Pete Decker, for instance, track down a homicidal kidnapper who has lured a boy away from an ultra-Orthodox family in New York. The boy’s sheltered environment has left him unworldly and naive in terms of street smarts but also curious about the allure of the secular world. Consequently, he is unusually vulnerable to kidnapping. Centering on this kind of tension, Kellerman poses the question: Is the world of strict religious practice a prison or a refuge?

While some readers identify with things Jewish and seek light reading that reflects their interests, other readers are curious about a set of mores and a milieu that are unfamiliar. Since Harry Kemelman’s hugely successful mystery series featuring Rabbi David Small, beginning with Friday the Rabbi Slept Late (1965), the combination of Jewish themes with mystery fiction has included efforts to explain Jewish culture to those who know little about it. While Kemelman emphasizes the sleuthing skills of the rabbi, which derive from his talmudic thinking and his ratiocinations, Kellerman’s novels place more emphasis on Judaism as comforting contrast to the violent, crime-ridden world so familiar to contemporary America. If readers take pleasure in seeing criminals brought to justice and order restored, Orthodoxy with its orderliness and clear guidelines for behavior appears as an appealing alternative. At the same time, Kellerman’s themes and her chosen genre do create jarring incompatibilities. Her mysteries at once present Jews in a positive way but also allow for a kind of titillating voyeurism. This fiction provides readers a chance to peek into the world of the pious and to see when it has gone awry: when it is most vulnerable, how it has been targeted by hatred, and when that world itself has produced criminals who find its strictures overbearing and so respond in pathological ways.

Kellerman was not alone in her attention to religion. Rochelle Krich, for example, adopts an Orthodox setting in Till Death Do Us Part (1992), where she combines a focus on Jewish law with feminist themes. In this novel a young Woman who cannot remarry, either because her husband cannot or will not give her a divorce (get) or because, in his absence, it is unknown whether he is still alive.agunah, a woman whose husband refuses to give her a writ of divorce, wishes that he were dead. Subsequently, he is murdered, and she becomes the prime suspect. In Krich’s Angel of Death (1994), a police detective discovers Jewish connections in her own mysterious past, even as she finds that the High Holiday liturgy contains important clues to the murder mystery she must solve. And in Speak No Evil (1995), Krich creates another Orthodox protagonist, a defense attorney who puzzles over ways to reconcile Jewish law and ethical teachings with American civil law in order to pursue justice.

Other writers emphasized Jewish ethnicity more than religious practice. Marissa Piesman, for instance, in her Nina Fischman mysteries (Unorthodox Practices, 1989; Personal Effects, 1991; Heading Uptown, 1993; Close Quarters, 1994) creates a very funny protagonist-narrator who flaunts her ethnic background and comments at length on the attitudes, values, and humor of a secular Jewish New York milieu. Israeli author Batya Gur found great popularity in English translation, thus adding to the trend for Jewish settings and characters. Her novels The Saturday Morning Murder (1988), A Literary Murder (1991), and Murder on A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.Kibbutz (1994) have a subversive edge as they examine what has gone rotten and led to murder in the elite institutions of Israeli society: a psychoanalytic institute, a kibbutz, a university. Serita Stevens and Rayanne Moore offer a spoof of the mystery genre in several novels featuring Fanny Zindel, a grandmother in her sixties who recounts her adventures in a thick, stylized Yiddish accent (Red Sea, Dead Sea, 1993; Bagels for Tea, 1993). As the stereotype dictates, she kvetches about her arthritis, frets that her granddaughter does not eat enough, plays the busybody, and acts the matchmaker with acquaintances she barely knows. At the same time, she stumbles repeatedly onto murder scenes and bumbles her way successfully through tangled webs of deception and international intrigue. Fanny foils villains right and left, and even outmaneuvers the Mossad on her first visit to Israel.

The Fanny Zindel mysteries overlap generically with the spy thriller. At times, that genre has been approached seriously by women authors. For instance, Susan Isaacs’s Shining Through (1990) features a female protagonist who spies on Nazi Germany and rediscovers her own Jewish ancestry in the process. Carolyn Haddad published a number of thrillers with Israeli settings. Haddad also contributed to this genre, however, by spoofing it, much as do Stevens and Moore. In The Academic Factor (1980), a professor of sociology travels from Columbus, Ohio, to Europe to attend a conference and inadvertently finds herself embroiled in international espionage. Hunted by an assortment of double agents, she ends up in Israel, confounding a husband, a pretend husband, and a lover—all named Saul. As was the case with Fanny Zindel, this fiction presents a comic rejoinder to the narrow or limited roles often demanded of women. Both the grandmother and the bookish academic break out of their stereotypes in rollicking escapades that allow them to outsmart and outfight the most macho of spies and thugs.

These examples indicate that women have explored a spectrum of possibilities in crime fiction and thrillers: From whodunits (Isaacs and Piesman) to entertainment with a serious side (Kellerman’s positive portraits of Orthodoxy and Krich’s protest on behalf of agunot), to detective stories that emphasize social observation (Gur), to the comic action-packed escape fantasies of Haddad or Stevens and Moore, all of this fiction envisions new roles and new images of Jewish women.

Science Fiction and Fantasy

Jewish themes, once unheard of in science fiction, emerged in that genre after the end of World War II, and particularly beginning in the 1970s. While Jewish authors once sought pseudonyms to disguise their Jewishness, more and more writers came to recognize rich potential in Jewish content for science fiction stories and novels. Two anthologies of Jewish science fiction and fantasy, Wandering Stars (1974) and More Wandering Stars (1982), edited by Jack Dann, include a number of stories by women. Carol Carr (in “Look, You Think You’ve Got Troubles”) imagines a Jewish father lamenting that his daughter has married a Martian. “Tauf Aleph” by Canadian author Phyllis Gotlieb raises the question, Who (or what) is a Jew? In this story, the last Jew in the universe lies dying on the planet Tau Ceti IV. He worries that he has no one to say Lit. (Aramaic) "holy." Doxology, mostly in Aramaic, recited at the close of sections of the prayer service. The mourner's Kaddish is recited at prescribed times by one who has lost an immediate family member. The prayer traditionally requires the presence of ten adult males.Kaddish for him, except for the walruslike creatures of his planet, whom he has instructed in prayer, plus the robot (Og Hagolem), who has vast information stored in his memory regarding Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah, Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmud, (Aramaic) A work containing a collection of tanna'itic beraitot, organized into a series of tractates each of which parallels a tractate of the Mishnah.Tosefta, Commentaries, Halakhic decisions written by rabbinic authories in response to questions posed to them.responsa and more. Posing the question, Do they qualify to say Kaddish or not? Gotlieb’s story plants hope for the continuity of Jewish tradition far into the distant future.

Marge Piercy, well-known for her fiction, essays, and poetry, draws on conventions of science fiction in some of her novels. The best known of these is Woman on the Edge of Time (1976), in which the main character lives simultaneously in contemporary America and in the year 2137. In He, She and It, Piercy combines elements of science fiction with her interest in Jews and feminism. The Jewish, female protagonist of this dystopia lives in the mid-twenty-first century. She helps create a cyborg, a kind of robot endowed with feeling as well as thought. Deliberately recalling the legends of the golem and the mysticism of the The esoteric and mystical teachings of JudaismKabbalah, Piercy raises questions about what constitutes personhood and whether the needs for personal and communal defense justify violence. Depicting a world devastated by war and ecological ruin, the author imagines innovative sexual and family relationships that provide an alternative to oppression as well as hope for a revitalized and nurturing future.

Along with Piercy, Rhoda Lerman has been recognized as an innovative author who combines elements of science fiction and fantasy with Jewish thematics. Though difficult to categorize generically, Call Me Ishtar (1973) addresses the exclusion of Jewish women from religious and social power by imagining a return of the goddess Ishtar.

Conclusion

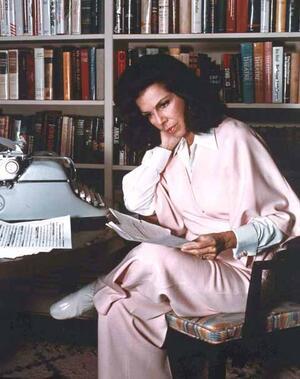

Many other Jewish women authors achieved great popularity and renown in the last decades of the twentieth century. Names such as Judith Krantz and Jacqueline Susann became synonymous with commercial success in the publishing world. (As of 1997, Susann’s Valley of the Dolls (1966) was still the world’s bestselling adult novel of all time, having sold over twenty million copies.) It should be noted that some of these writers did not write explicitly on Jewish topics. Some also had tenuous or complicated connections with their Jewishness. Susann, for example, was born Jewish and was buried as a Jew, but lived much of her adult life as a Catholic. Other writers explicitly incorporated Jewish characters and themes of social prejudice into their best-selling fiction, for example, Rona Jaffe, Class Reunion (1979).

A notable number of women writers were known for their humor. Bel Kaufman, granddaughter of Sholem Aleichem, wrote the well-loved, humorous account of high-school teaching, Up the Down Staircase (1965). Comedian Joan Rivers hit the best-seller charts in 1984 with The Life and Hard Times of Heidi Abromowitz, as did Bette Midler with her madcap illustrated fable in verse, The Saga of Baby Divine, in 1983. In Heartburn (1984), a witty, bittersweet account of a marriage and its breakup, Nora Ephron writes of her protagonist’s Jewish background with humor and irreverent affection. Iris Rainer Dart offers portraits of Jewishness itself as a heritage of humor. Whether writing on romantic love (Till The Real Thing Comes Along, 1987), friendships between women (Beaches, 1985), or unusual family issues of the twentieth century, such as surrogate mothering and test-tube pregnancies (The Stork Club, 1992), Dart presents warmth, humor, and family closeness as enduring, unpretentious values. Her Jewish characters cherish everyday moments. For them, not losing sight of their heritage or of humble beginnings is at once a source of strength and an antidote to glitz, glamour, and superficial values. The humor of Nora Ephron and Iris Rainer Dart is as well known from their scriptwriting (screenplays and television) as from their fiction.

As Jewish women came to constitute a strong presence in American popular fiction, their work increasingly featured an assertively Jewish component combined with the construction of strong women characters. To be sure, this writing expressed a mix of attitudes. Along with pride in Jewishness, there is ambivalence and at times self-hatred, but the wide variety of books and stories published reveals many ways to be Jewish in the contemporary world and many opportunities open to women. Even a brief survey shows female characters as Orthodox Jews, as ethnic Jews, as indifferent Jews, as Jews concerned with the Holocaust, as JAPs and as women who rebel against the JAP stereotype, as futuristic, visionary Jews, and as Jews intent on rewriting and reconceiving women’s place in religion. And, to the extent that popular fiction lets out the reins of the imagination, relying as it does on fantasy and a spectrum of imagined worlds and actions, women characters in this literature can be anything—from royalty to inhabitants of outer space, from heroic figures in the Civil War to high fashion models, not to mention entrepreneurs, writers, actors, detectives, doting grandmothers, and spies.

To the extent that this kind of writing has mass appeal, these authors spread an awareness of Jewishness into the mainstream of American popular culture. At the same time, they used the formulas of genre fiction to explore Jewish identity. Regional novels comfortably accommodated portraits of Jewish immigrants and pioneers and their contributions to the American dream. Historical fiction and romance lent themselves naturally to themes of assimilation and intermarriage. Mysteries just as naturally became a forum for examining Jewish law and transgressions of it, highlighting the security and the restrictions that traditional Judaism offers observant Jews. Thrillers focusing on Israel tussled with the twentieth-century redefinition of the Jew as warrior, not as scholar. Science fiction discovered that it lends itself to Jewish themes in the most imaginative and whimsical ways. Drawing on Jewish legends, it projects age-old Jewish concerns into limitless future worlds.

Antler, Joyce. “Jewish American Writing: Overview.” In The Oxford Companion to Women’s Writing in the United States, edited by Linda Wagner-Martin (1995).

Baum, Charlotte, Paula Hyman, and Sonya Michel, eds. The Jewish Woman in America (1976).

Burch, Beth. “Jewish American Writing: Fiction.” In The Oxford Companion to Women’s Writing in the United States, edited by Linda Wagner-Martin (1995).

Fishman, Sylvia Barack. “American Jewish Fiction Turns Inward, 1960–1990.” AJYB 91 (1991): 35–69.

Fishman, Sylvia Barack. “The Faces of Women: An Introductory Essay.” In Follow My Footprints: Changing Images of Women in American Jewish Fiction, edited by Sylvia Barack Fishman (1992).

Forman, Ed, Martin H. Greenberg, and Larry Segriff, eds., with Jon L. Breen. The Mystery Reader’s Indispensable Companion (1993).

Greene, Suzanne Ellery. Books for Pleasure, 1914–1945 (1974).

Hackett, Alice. Eighty Years of Best Sellers, 1895–1975 (1977).

Hinckley, Karen, and Barbara Hinckley. American Best Sellers: A Reader’s Guide to Popular Fiction (1989).

Lichtenstein, Diane. “Fannie Hurst and Her Nineteenth-Century Predecessors.” Studies in American Jewish Literature 7, no. 1 (1988): 26–39.

Lichtenstein, Diane. Writing Their Nations: The Tradition of Nineteenth-Century American Jewish Women Writers (1992).

Prell, Riv-Ellen. “Cinderellas Who (Almost) Never Become Princesses: Subversive Representations of Jewish Women in Post-War Popular Novels.” In Talking Back: Images of Jewish Women in American Popular Culture, edited by Joyce Antler (1998).

Shands, Kerstin W. The Repair of the World: The Novels of Marge Piercy (1994).

Shapiro, Ann R., ed. Jewish American Women Writers: A Bio-Bibliographical and Critical Sourcebook (1994).

Templin, Charlotte. Feminism and the Politics of Literary Reputation: The Example of Erica Jong (1995).

Uffen, Ellen Serlen. “The Novels of Fannie Hurst: Notes Toward a Definition of Popular Fiction.” Journal of American Culture 1 (1978): 574–83.

Uffen, Ellen Serlen. “The Orthodox Detective Novels of Faye Kellerman.” Studies in American Jewish Literature 11, no. 2 (1992): 195–203.