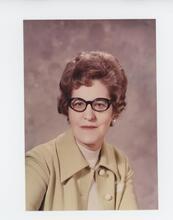

Carolyn G. Heilbrun

A leader in the American feminist movement, Carolyn G. Heilbrun earned her Ph.D. from Columbia University in 1959 and was appointed to an instructorship in English at Columbia’s adult extension program. Heilbrun was tenured in 1971 and given an endowed chair in 1986. She retired early in 1993 to protest the university’s continued discrimination against women. Heilbrun wrote some of the women’s movement’s most widely read texts, including Toward a Recognition of Androgny (1973) and Reinventing Womanhood (1979). These texts encouraged readers to reconceive the role of women in society and challenge conventional notions of masculinity. In Writing a Woman’s Life (1988) she analyzed ecamples of independent women intellectuals. In 1995 Heilbrun published a biography of Gloria Steinem. Heilbrun also published mystery novels beginning in 1964 under her pen name, Amanda Cross.

Throughout her life, Carolyn G. Heilbrun successfully managed to sustain a triple career. As wife and mother, literary academic, and mystery writer, her ultimate goal was to encourage women to strive for intellectual and professional independence.

Family

Carolyn (Gold) Heilbrun was born on January 13, 1926, in East Orange, New Jersey, the only child of Archibald and Estelle (Roemer) Gold. Her father, who came to America from Russia around 1900 as a destitute, Yiddish-speaking child, became a certified public accountant and rose to riches as a partner in a brokerage firm. He lost his wealth in the Depression, and in 1932 the family moved to Manhattan on borrowed money. Although Carolyn’s father gradually rebuilt his fortune, her mother remained deeply traumatized by the family’s sudden loss of security and social status. Born in America to religious Austrian-Jewish parents as the first of seven children, Estelle Roemer cut her ties to the Jewish world as a young woman. According to Heilbrun, she “identified all that limited her life as Judaism.” Archibald Gold, whom she married in 1919 when both were twenty-three years old, had also distanced himself from his Jewish past.

Education & Teaching Career

Not surprisingly, the family turned to a consoling form of American Protestantism in times of spiritual need. Socially and financially still fragile, the Golds began to attend the Divine Science Church of the Healing Christ in the mid-1930s and sent their daughter to its Sunday school. She was educated at an all-girls private preparatory school in Manhattan. She went on to Wellesley College, where she earned her B.A. in 1947. On February 20, 1945, she married James Heilbrun, with whom she had three children. Her marriage, which she called probably the single most fortunate factor in her life, offered her some of the resilience and strength she needed to pursue a career as an English literary scholar in the still male-dominated world of Ivy League academe. Having earned her M.A. in 1951 and her Ph.D.—with a biography of The Garnett Family (1961)—in 1959 from Columbia University, she was appointed, after a brief teaching stint at Brooklyn College, to an instructorship in English at Columbia’s School of General Studies, the university’s adult extension program. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the School of General Studies served as the only gateway to academic careers for women scholars at Columbia. Heilbrun was tenured in 1971, appointed to a full professorship in 1972, and given an endowed chair in 1986. In 1993, she took early retirement to protest the university’s continued discrimination against women.

Heilbrun received many honors and awards over the course of her lifetime. She was a Guggenheim Fellow (1966, 1970), a Bunting Institute Fellow at Radcliffe College (1976), a Rockefeller Fellow (1976–1977), and a National Endowment for the Humanities Senior Research Fellow (1983). She served as a member of the executive council of the Modern Language Association (1976–1979) and as MLA president in 1984.

Publications & Involvement in the Women’s Movement

Although Heilbrun claimed that she “had been born a feminist and never wavered from that position,” men rather than women dominated her early career. Her father was her acknowledged role model, Lionel Trilling (Columbia’s éminence grise) was her academic idol, and her second book was a study of the poet Christopher Isherwood (1970). But as the women’s movement gathered momentum, Heilbrun began to write some of its most widely read texts. In 1973, she published Toward a Recognition of Androgyny, in which she pleaded for a modification of conventional notions of masculinity in the direction of feminine traits, in order to stem the self-brutalization and destructiveness experienced by an American society unable to extricate itself from the Vietnam War. Six years later, Heilbrun sharpened her plea by urging women to reinvent their role in society. Her book Reinventing Womanhood(1979) was not only an analysis of women’s contribution to English literature and culture, but a manifesto of independence, containing suggestions on “how a woman might convert the materials of her male-centered education into a guide for female accomplishment.”

Heilbrun’s next book, Writing a Woman’s Life (1988), provided examples of independent women intellectuals. Its six chapters were devoted to George Sand, Dorothy Sayers, women poets and their fathers, women novelists and marriage, and women writers and friendship. The last chapter explained the invention of Amanda Cross in 1963, Heilbrun’s persona as a mystery writer, and Cross’s creation of professorial sleuth Kate Fansler. Heilbrun rounded off her academic work with the publication in 1990 of Hamlet’s Mother and Other Women, a collection of her essays on women in fiction and culture written during the 1970s and 1980s. In 1995, Heilbrun ventured into new territory with her biography of a living person, The Education of a Woman: The Life of Gloria Steinem. With this book, Heilbrun intellectual life came full circle. As a young girl, she had been an avid reader of biographies because they allowed her, as she explained, “to enter the world of daring and achievement.” As a seasoned cultural critic, she put her pen to the service of future readers by chronicling the daring and achievement of one of America’s most prominent feminist activists.

The mysteries that Heilbrun began publishing in 1964 under the pen name Amanda Cross (eleven to date) offer occasional glimpses of life in academe. Her amateur detective, Kate Fansler—a gutsy, childless, elegant literature professor of WASP descent and upper-class upbringing, who in ripe middle age marries a man younger than herself—has charmed a large audience and allowed her author to familiarize, in an entertaining way, a readership outside the university with issues alien to their everyday world. A number of the books deal with the precarious situation of women (and minorities) in academe (Poetic Justice, 1970; Death in a Tenured Position, 1981; Sweet Death, Kind Death, 1984; A Trap for Fools, 1989; An Imperfect Spy, 1995). Others portray the eccentric lives of women writers and their ambitious biographers (The Question of Max, 1976; No Word from Winifred, 1986; The Players Come Again, 1990).

Legacy & End of Life

Like many American Jewish women who grew up materially privileged but estranged from their Jewish roots, Carolyn G. Heilbrun worked hard to create a significant identity for herself. The women’s movement provided her with a framework within which she could rethink not only her field (modern British literature), but also herself. In the process, she wrote inspiring critical studies that reconsidered the stature of European women writers, encouraged her readers to reconceive the role of women in society, and propelled her to the forefront of American feminism.

Carolyn Heilbrun died on October 9, 2003, having chosen to end her own life. “She wanted to control her destiny,” her son Robert said, “and she felt her life was a journey that had concluded.” Heilbrun had reflected on the appropriateness of suicide for the elderly some years earlier, in The Last Gift of Time: Life Beyond Sixty, in which she wrote of being “half in love with easeful death,” and confided her determination to commit suicide at seventy. Ultimately, she waited an additional seven years before choosing—consciously and rationally—to write the ending of her own existence.

Selected Works by Carolyn G. Heilbrun

Christopher Isherwood. New York: Columbia University Press, 1970

The Education of a Woman: The Life of Gloria Steinem. New York: Ballantine Books, 1995

The Garnett Family. London: Allen & Unwin, 1961

Hamlet’s Mother and Other Women. New York: Columbia University Press, 1990

Lady Ottoline’s Album: Snapshots and Portraits of her Famous Contemporaries (and of Herself), editor. New York: Knopf, 1976.

The Last Gift of Time: Life Beyond Sixty. New York: Ballantine, 1998

Reinventing Womanhood. New York: Norton, 1979

The Representation of Women in Fiction, editor, with Margaret R. Higgonet. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983

Toward a Recognition of Androgyny. New York: Knopf, 1973

Writing a Woman’s Life. New York: Ballantine, 1988

Mysteries Written as Amanda Cross

Death in a Tenured Position. New York: Ballantine, 1981

An Imperfect Spy. New York: Ballantine, 1995

In the Last Analysis. New York: Macmillan, 1964

The James Joyce Murders. New York: Macmillan 1967

No Word from Winifred. New York: Ballantine, 1986

The Players Come Again. New York: Random House, 1990

Poetic Justice. New York: Avon, 1970

The Question of Max. New York: Knopf, 1976

Sweet Death, Kind Death. New York: Ballantine, 1984

The Theban Mysteries. New York: Avon, 1979

A Trap for Fools. New York: Ballantine, 1989)

Bibliography

Directory of American Scholars. Vol. 2, English, Speech and Drama (1982)

The International Who’s Who of Women. London, Europa Publications, 1992

Klingenstein, Susanne. “‘But My Daughters Can Read the Torah’: Careers of Jewish Women in Literary Academe.” American Jewish History 83 (1995): 247–286, and Enlarging America: The Cultural Work of Jewish Literary Scholars, 1930–1990 (1998)

Who’s Who in America (1996)

McFadden, Robert; “Carolyn Heilbrun, Pioneering Feminist Scholar, Dies at 77.” New York Times, October 11, 2003

Gilbert, Sandra and Susan Gubar. “Carolyn Gold Heilbrun.” The Guardian, October 30, 2003.

Directory of American Scholars. Vol. 2, English, Speech and Drama (1982)

The International Who’s Who of Women. London, Europa Publications, 1992

Klingenstein, Susanne. “‘But My Daughters Can Read the Torah’: Careers of Jewish Women in Literary Academe.” American Jewish History 83 (1995): 247–286, and Enlarging America: The Cultural Work of Jewish Literary Scholars, 1930–1990 (1998)

Who’s Who in America (1996)

McFadden, Robert; “Carolyn Heilbrun, Pioneering Feminist Scholar, Dies at 77.” New York Times, October 11, 2003

Gilbert, Sandra and Susan Gubar. “Carolyn Gold Heilbrun.” The Guardian, October 30, 2003.