Phyllis Chesler

Feminist, author, and scholar Phyllis Chesler is an Emerita Professor of Psychology and Women’s Studies at City University of New York. She has pioneered many issues in her research, writing, and activism, including the mistreatment of women in cases of rape and incest; the psychological importance of female role models; the class, race, sexuality, and sex biases of psychotherapists; the importance of believing women’s testimony; rape; prostitution; pornography; surrogacy; and antisemitism among Western intellectuals and Islamists. Her involvement in feminism was forged during a period of captivity in Afghanistan and in her involvement in the civil rights and anti-war movements of the 1960s. After encountering antisemitism on the left, she became involved in Jewish feminism. Her outspokenness on antisemitism and Muslim misogyny have made her a controversial figure.

Overview

Phyllis Chesler is an Emerita Professor of Psychology and Women’s Studies at City University of New York; the author of twenty books and thousands of articles, which have been translated into many European languages and into Japanese, Korean, Chinese, and Hebrew; a pioneering radical feminist leader, and a former psychotherapist. She is also a committed Jew and Zionist. Chesler currently submits courtroom affidavits on behalf of women who are in flight from being honor-killed.

Chesler’s books include the landmark classic Women and Madness (1972), which has sold three million copies (the first feminist work to receive a front-page review in the New York Times Book Review).

Family and Education

Born on October 1, 1940, Chesler and her two younger brothers grew up in an Orthodox Jewish family in Borough Park, Brooklyn. Her mother, Lillian (Hammer), was eventually a school secretary, and her father, born in Lutzk and orphaned when his mother was murdered by Cossacks, delivered seltzer and soda. Chesler believes she was a born rebel, but she also traces her understanding of oppression and liberation back to her experiences as a child when, at age eight, she joined Ha-Shomer ha-Tza’ir, a radically left and secular Zionist youth organization, and later En Harod, an even more visionary Zionist youth group.

Chesler attended Bard College on a scholarship, where she met and married an Afghan reformer who took her to see his family. There he reverted to traditional mores, while her mother-in-law tried to convert her to Islam. Chesler managed to escape with the help of her father-in-law, but she never forgot the experience of gender apartheid that shaped her and every woman’s life in Afghanistan.

Upon return, she worked full-time while attending graduate school at the New School for Social Research. She worked in a Brain Research Lab, obtained a fellowship in Neurophysiology at New York Medical College, published two articles in Science Magazine—and then received her PhD in psychology in 1969.

Chesler also co-founded the Association for Women in Psychology in 1969 and the National Women’s Health Network in 1975. She delivered a keynote speech at the first-ever “Speak-Out on Rape” in 1971 in New York City. She also taught the first course in women’s studies at Richmond College at City University of New York in 1970; it later became an accredited course of study at every campus within the CUNY system.

Pioneering Writer and Activist

Chesler has pioneered many issues in her research, writing, and activism, including the mistreatment of women in cases of rape and incest, the psychological importance of female role models, the class, race, sexuality, and sex biases of most psychotherapists, the importance of believing women’s testimony (Women and Madness), rape, prostitution, pornography (About Men), woman-battering, and the scandal of good mothers losing custody even when pitted against abusive husbands and fathers (Mothers on Trial).

In addition, Chesler documented the misogynist nature of commercial surrogacy, and the ways in which this practice is yet another kind of custody battle between the wealthy and the impoverished (Sacred Bond). She co-edited Feminist Foremothers and wrote Letters to a Young Feminist in an attempt to transmit a Second Wave legacy to the coming generations.

In 2002, Chesler co-edited Women of the Wall, an anthology of the original women leaders and those who prayed with them at the Western Wall in Jerusalem for the first time on December 1, 1988. In the same year, she also published Woman’s Inhumanity to Woman, which documented the ways in which women are aggressive and competitive towards each other and have internalized sexist beliefs. She continued this work in A Politically Incorrect Feminist.

In 2003, Chesler published The New Anti-Semitism in response to the alarming rise of antisemitism among Western intellectuals and Islamists. In a series of articles, she discussed the nature of Islamic Jew-hatred, Jihad terrorism and the treatment of women, dissidents, apostates, and gays in Muslim countries. She expanded this work in a series of books (An American Bride in Kabul; Islamic Gender Apartheid; A Family Conspiracy: Honor Killing). She also mourned the failure of most feminists to confront misogyny in Arab and Muslim culture (The Death of Feminism).

In 2020, Chesler published Requiem for a Female Serial Killer, which focuses on violence against prostituted women and a prostitute’s right to kill in self-defense.

Her work has been translated in many European languages, and into Japanese, Korean, Chinese, and Hebrew.

Jewish Feminism

Chesler’s involvement with feminism predated her involvement with Jewish feminism and was forged in the fires of her captivity in Kabul and in her involvement in the civil rights and anti-war movements of the 1960s. Chesler has always believed that “the kind of feminist I am has everything to do with my Jewish passion for justice.”

Chesler’s feminist tendencies first appeared in 1952 when she wanted a bat-mitzvah, something Orthodox congregations did not yet accept. Her direct involvement with Jewish feminism began in 1971, when she encountered different forms of Jew-hatred among leftists and among lesbian feminists. She started wearing a large Jewish star around her neck when she delivered radical and left feminist speeches. Her first visit to Israel in December 1972 began a long-standing connection with the then-nascent Israeli feminist movement. She gave feminist speeches and held meetings in Tel Aviv, Haifa, and Jerusalem during the 1970s and 1980s.

In the United States, with a handful of other Jewish feminists, including Aviva Cantor Zuckoff and Cheryl Moch, Chesler issued a press release and helped plan the first-ever conference about Judaism and feminism, which took place in 1973 at the McAlpin Hotel in New York City. In the 1970s, she also sought feminist signatories for petitions that opposed the UN’s Zionism=Racism resolution. In an interview with Lilith Magazine (winter 1976–1977), Chesler advocated the creation of “feminist sovereign space,” drawing a parallel between feminism and Zionism.

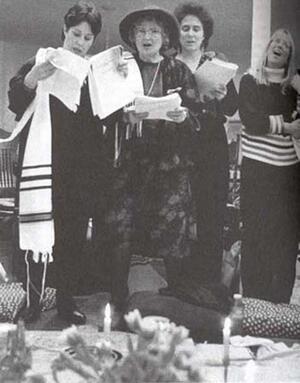

In the 1970s and 1980s, Chesler created alternative rituals for Jewish holidays and life-cycle events. She also organized and hosted the first feminist seders, based on a preliminary Haggadah written by E.M. Broner and Naomi Nimrod, in Chesler’s Manhattan apartment. As Chesler became more Torah-literate, she left the more secular, political, and Consciousness-Raising style of feminist Lit. "order." The regimen of rituals, songs and textual readings performed in a specific order on the first two nights (in Israel, on the first night) of Passover.seder. She now attends an Orthodox synagogue and sometimes publishes commentaries on the Torah.

In 1988, at an international conference of Jewish women, Chesler participated in the first-ever women’s prayer service at the Kotel (Western Wall). She was asked to open the Torah, and that act wedded her to the grassroots, legal, and religious struggle to secure women’s right to pray at this holy site. Together with Rivka Haut, her Torah study partner (chevrutah), Chesler co-founded the International Committee for Women of the Wall; she was a named plaintiff in the ongoing Israeli legal struggle on behalf of Jewish women’s prayer rights in Jerusalem.

Feminist seders have provided an important context for developing women’s spirituality. In 1975, a group of Israeli and American women decided to create their own Passover seder based on their experiences as Jewish women. Now an annual event held in Manhattan, it has been attended by Esther Broner, Gloria Steinem, Letty Cottin Pogrebin, Bella Abzug, Grace Paley and several other "Seder Sisters" who have played important roles in the development of Jewish feminism. Shown here are Bella Abzug, Phyllis Chesler and Letty Cottin Pogrebin at the Women's Seder in 1991.

Photo: Joan Roth

Confronting Antisemitism

In 1980, while working for the United Nations, Chesler attended the UN’s World Conference on Women in Copenhagen, where the NGO panels scapegoated Israel as the world’s whipping girl and focused upon “Palestine,” not women. She then published a second article in Lilith, this time using the pseudonym she had been assigned to expose the conference’s antisemitism/anti-Zionism. She also organized a panel at the 1981 National Women’s Studies Association to address the issue of Jews and Israel among feminists.

In 2003, she published a book about the rise of a “new anti-Semitism” in the wake of the Intifada of 2000. It was barely reviewed in the mainstream and feminist media; most feminists did not read it, and those who did objected to her criticism of antisemitism among the Western “progressive” intelligentsia and the Islamic world.

Experiences with the Muslim World

In 2013, Chesler published An American Bride in Kabul, which won the National Jewish Book Award that year. She describes her love affair with a young Muslim man from Afghanistan whom she met at college. They married in a secular ceremony and traveled to Kabul, where her American passport was taken away. She became the property of a large, polygamous family. She discovered that her father-in-law had three wives and twenty-one children, and that she was expected to live with her mother-in-law—all pro forma in the Muslim world. In essence, she found herself in captivity, in fairly posh purdah. Once she was able to escape and return to college, she found intellectuals, including feminists, remarkably resistant to reports on the misogyny there. They categorically refused to take a position on the burqa, hijab, child marriage, polygamy, and honor-killings, all of which Chesler termed “gender apartheid.” This reluctance arose from their commitment to multi-cultural relativism and anti-imperialism, which resulted in Western feminists refusing to condemn misogynist crimes committed by men of color toward women of color. Those who dared condemn such misogyny were themselves condemned as colonial racists. Increasingly, Chesler believed, many Western feminists were more concerned about the occupation of a country that has never existed—Palestine—than with the occupation of women’s bodies in the Muslim world

Chesler’s outspokenness on antisemitism and Muslim misogyny, combined with her Zionism, have elicited some hostility from feminists and Islamists.

Chesler is the author of four studies about honor killing (“intimate family femicide” or “shame-murders”), and based on these studies, she submits affidavits for Muslim and ex-Muslim women in flight from being honor killed and in search of political asylum.

Chesler serves on the editorial board of Dignity: A Journal of Analysis of Exploitation and Violence and is a Senior Fellow at the Investigative Project on Terrorism and a Fellow at the Middle East Forum and the Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy.

In addition to her many books, Chesler has also published widely in the press, including in the Globe and Mail, LA Times, Guardian, New York Times, Times of London, Washington Post, American Thinker, FOX, FrontpageMag, Israel National News, Middle East Quarterly, New English Review Press, New York Post, Tablet Magazine, etc.

Chesler has one son, Ariel David Chesler, the child she had with her Israeli husband, and who is now a judge and married to Shannon Berkowsky. She and her partner, Susan L. Bender, are proud grandmothers to two spirited and beautiful granddaughters.

Selected Works

Women and Madness. New York: Doubleday and Company, 1972.

Women, Money and Power. New York: William Morrow & Company, 1976.

About Men. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1978.

With Child: A Diary of Motherhood. Philadelphia: Lippincott & Crowell, 1979.

Mothers on Trial: The Battle for Children and Custody. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1986, 2011 (Chicago Review Press, updated with eight new chapters).

Sacred Bond: The Legacy of Baby M. New York: Times Books/Random House, 1988.

Patriarchy: Notes of an Expert Witness. Monroe, ME: Common Courage Press, 1994.

Feminist Foremothers in Women's Studies, Psychology, and Mental Health. Contributor and Co-editor with Ellen Cole and Esther Rothblum. Philadelphia: The Haworth Press, 1996.

Letters to a Young Feminist. New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 1998.

Woman's Inhumanity to Woman. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press/Nation Books, 2002.

Women of the Wall: Claiming Sacred Ground at Judaism’s Holy Site. Co-editor, with Rivka Haut. Woodstock, VT: Jewish Lights Publishing, 2002.

The New Anti-Semitism: The Current Crisis and What We Must Do About It. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Wiley, 2003. Republished by Gefen Publishing with new Introduction, 2014.

The Death of Feminism: What’s next in the Struggle for Women’s Freedom? London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

An American Bride in Kabul. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Living History: On the Front Lines for Israel and the Jews 2003-2015. Jerusalem: Gefen Publishing House, 2015.

Islamic Gender Apartheid: Exposing a Veiled War Against Women. Nashville, TN: New English Review Press, 2017.

A Family Conspiracy: Honor Killing. Nashville, TN: New English Review Press, 2018.

A Politically Incorrect Feminist. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2018.

Requiem for a Female Serial Killer. Nashville, TN: New English Review Press, 2020.