Lilith Magazine

Founder and editor of Lilith, the "independent Jewish women's magazine," Susan Weidman Schneider is devoted to the many causes of concern to Jewish women and to highlighting the unique challenges and possibilities facing those who make a commitment to both Judaism and feminism. Photograph by Joan Roth.

Institution: Lilith

Founded in 1976 and named after the biblical figure who represents the quintessential female rebel, Lilith magazine seeks to create a space where Jewish women can learn about and discuss feminism and women’s issues. The magazine’s content is not confined to a specific genre and is very broad, ranging from the efforts to begin ordaining women rabbis to women’s health issues. Lilith’s articles are written by authors of all backgrounds and ages, and the magazine also offers other resources, such as a traveling exhibition that used literature from the publication to examine issues pertinent to Jewish women. The topics discussed in Lilith have stimulated a great deal of thinking and, indeed, fostered change within the Jewish community.

History and Naming

Founded in 1976 by a small group of women led by Susan Weidman Schneider “to foster discussion of Jewish women’s issues and put them on the agenda of the Jewish community, with a view to giving women—who are more than fifty percent of the world’s Jews—greater choice in Jewish life,” Lilith: The Independent Jewish Women’s Magazine has remained true to its mission. From its inception, it has intentionally, though not exclusively, emphasized religious and social issues, with somewhat less focus on areas such as economics or politics. In 2004 the editors changed the tag line on the cover to read “independent, Jewish & frankly feminist.” The contours of the Jewish women’s movement and its own consciousness of a role that exceeds that of a magazine can be traced through nearly three decades of publication.

Although during its initial years publication was sporadic, the magazine has settled into a regular rhythm of quarterly issues. About half of the ten thousand copies printed go to subscribers; the rest are sold on newsstands or distributed as single copies. The readership is estimated to be twenty-five thousand. Advertising, sparse since Lilith’s inception, has grown, but it continues to cover a relatively small proportion of the cost of the magazine. Subscriptions, tax-deductible contributions, and grants cover the rest.

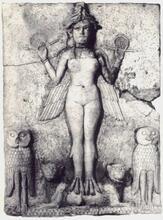

The character Lilith, whom the magazine honors in its name, was the mythic first partner of Adam. While absent from the biblical text of the creation story, she is assumed by later interpreters to have merited banishment from the Garden of Eden because she refused to do Adam’s bidding, particularly in sexual matters. She is the quintessential female rebel, a woman who would not take direction from a man. According to some rabbinic versions of this legend, her children were killed, leading her to attempt vengeance by killing infants. By taking her name, Lilith attempts a rehabilitation of her reputation and underscores the extent to which it identifies with the voices of women who are not afraid to take some risks to ensure gender equality.

Content

Lilith attempts both to engage the interest of feminists in Judaism and to heighten the feminist consciousness of Jews, particularly Jewish women. Its proudly proclaimed independence is not to be misconstrued as a lack of position. Rather, its position is precisely that women, specifically Jewish women, ought to strive to define themselves rather than passively accept the expectations of others. The range of features Lilith has covered over the years is fairly broad, as is the variety of its contributors. In the initial years, it focused on the religious and organizational establishment of the Jewish community. The struggle to ordain women at the Jewish Theological Seminary was, for example, carefully covered with frequent updates and articles.

The position of women in Jewish education and culture has also been examined, as has the place of women in Jewish organizational life. Lilith has chronicled the development of new women’s religious rituals and liturgy, reported on the position of women in Israeli life, and regularly addressed women’s health issues. Lesbianism is often a particularly difficult issue to deal with in a magazine like Lilith, but it is regularly covered and, indeed, the magazine has served as a “safe space” to raise this issue, along with giving voice to other often marginalized populations within the Jewish community. Lilith also publishes fiction and poetry, as well as thought-provoking reviews of books, films, theater, and music.

The topics discussed in Lilith have stimulated a great deal of thinking and, indeed, fostered change within the Jewish community. For example, Cynthia Ozick’s article “Notes toward Finding the Right Question: A Vindication of the Rights of Jewish Women” moved the question of women’s rights in Judaism from the sacred to the social domain. In so doing, she opened the issue for many who had considered the question in exclusively theological terms. The issue of so-called JAP-baiting on campus was also brought to the attention of a broad public through the pages of Lilith. An ongoing series by Susan Weidman Schneider has explored the differing ways women and men approach philanthropy. This research has had an impact on the United Jewish Communities-Federation world and on many others seeking to fund Jewish causes. Finally, an issue devoted to hair confronted Jewish women’s self-image.

Founder and editor of Lilith, the "independent Jewish women's magazine," Susan Weidman Schneider is devoted to the many causes of concern to Jewish women and to highlighting the unique challenges and possibilities facing those who make a commitment to both Judaism and feminism. Photograph by Joan Roth.

Institution: Lilith

The writers range from professional writers to professors to graduate students, and the articles are intended for well-educated laypeople rather than an academic audience. The letters to the editor reveal the breadth of the readership: North America and Israel clearly dominate geographically; many more women than men write letters, and they have a wide range of interests.

Mission

Lilith is impelled by a vision that is broader than a magazine. Both within its pages and beyond them, it is clearly attempting to effect fundamental change in Judaism and Jewish society. Thus, for example, the “Kol Ishah” [Woman’s voice] section presents short news items of particular interest to Jewish women. “Tsena Rena” [Go out, see] is subtitled “where to go for what if you’re Jewish and female.” It describes products and programs and includes information about contacting the providers. Each of these features draws its name from a piece of the traditional Jewish past and each challenges the original concept. Both of these features, part of the magazine since its inception, help Lilith foster change in the Jewish community.

It is the activities fostered by Lilith beyond the covers of the magazine that are most distinctive. Its editor-in-chief is, for example, regularly invited to speak at the General Assembly of the Council of United Jewish Communities, Jewish community centers, conferences, and other venues. Lilith has also developed a talent bank of more than four hundred Jewish women who can serve as resources in many fields. In 2002 Lilith created a traveling exhibition of ten large wall panels that explore, through excerpts from the magazine’s articles and illustrations, the most urgent issues in the lives of Jewish women since the magazine’s inception in 1976. The exhibition, traveling across North America, and the creation of a website (www.Lilith.org) with a searchable database of the Table of Contents of all back issues, have brought Lilith’s subject matter to new audiences. The partnership between the magazine and activists strengthens Lilith’s impact on the community.