Poetry in the United States

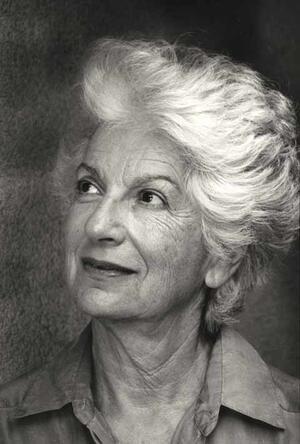

"I wanted to use what I was, to be what I was born to be—not to have a 'career,' but to be that straightforward obvious unmistakable animal, a writer," Cynthia Ozick once said. She has certainly achieved her goal. The winner of numerous literary awards, Cynthia Ozick is a writer par excellence, author of essays, plays, short stories and novels.

Institution: The Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives, Cincinnati, OH, www.americanjewisharchives.org and Gerard Murrell.

The tremendous diversity of Jewish American women’s poetry is a result of a balancing act between being Jewish, American, and female. Of course, the relationship among these three identities of a poet can shift from one poem to the next. Poetry allows for such contradiction: a poet may argue with traditional Judaism in one poem and celebrate it in another. American Jewish women poets share a sense of marginality. Jewish women’s poetry is often transformational, whether it is from within the Jewish world, or in American society at large. Writing from the margins—as Jews, as women—these poets often become the modern equivalent of prophets, critically evaluating and condemning existing circumstances and envisioning better ones.

What is a Jewish Poem?

What is a Jewish poem? Does it wear a yarmulke

and a tallis?

Does it live

in the Lit. (Greek) "dispersion." The Jewish community, and its areas of residence, outside Erez Israel.Diaspora

and yearn for homeland?

Myra Sklarew’s poem entitled “What Is a Jewish poem?” frames the question within the traditionally male stereotypes of what it is to be Jewish. Since she herself is a contemporary Jewish woman poet, a survivor of the Holocaust living in America, her poem forces the reader to confront a deeper, unspoken question: What constitutes a Jewish poem written by a woman in America? The male-centered attitude of Sklarew’s poem, which ludicrously refers to the Jewish poem as “little yeshiva bokher,” is, unfortunately, a fairly accurate assessment of the way in which literary critics have defined Jewish poetry.

In the essay “American-Jewish Poetry: An Overview,” R. Barbara Gitenstein points out the narrow focus of critics. She suggests that a student conducting an overview of American-Jewish literature might conclude that “there are no American-Jewish writers who are women, no writers who have lived in towns smaller than Chicago—and surely no writers who are poets.” Even among the few anthologies and literary surveys that emphasize poetry over prose, editors and scholars have favored primarily male poets, with token references to women. Few have attempted to evaluate the poetry of Jewish American women as a collective. While in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries Jewish women poets dotted the landscape of American poetry, more recently there has been a flourishing of women poets, many of whom choose to write on Jewish themes. Efforts, mostly by Jewish women poets and scholars, to anthologize and examine the tremendous range of these works have been the first tentative explorations in this rich and complex territory.

The Diversity of Jewish American Women’s Poetry

The question remains: What makes a poem “Jewish”? Is it enough that the poet is Jewish? Must the theme be Jewish? Is there such a thing as a Jewish “sensibility” or attitude in poetry? From the nineteenth century to the present, Jewish American women have written poetry to varied audiences in a dramatic range of form, style, and theme. To look exclusively at poems with Jewish content would be misleading. It ignores the possibility that the desire to write poetry that is not thematically Jewish may itself be a defining feature of the complex position of Jewish American women, and it overlooks poets whose Judaism influences their writing in more subtle ways. Just as poets whose work is not primarily Jewish deserve attention, it is also important to address women poets who identify themselves as Jews, although they may not be considered Jewish by The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhic law. A poet of such force and popularity as Adrienne Rich (1929-2012), for example, is often left out of anthologies because her mother was not Jewish.

The tremendous diversity of Jewish American women’s poetry is caused by a balancing act, or, in some cases, a full-scale war, between the three parts that make up the identity of the poet: Jewish, American, and female. What value does the poet place on each of these attributes? How is the poem able to integrate or juxtapose them? How does each poet define herself as a Jew, a woman, and an American? The compatibility of these three competing identities changes most significantly over historical time, but it is also affected by the poet’s position in society and religious commitment. Of course, the relationship among the Jewish, female, and American identities of a poet can shift from one poem to the next. One of the virtues of poetry is that it allows for such contradiction, so that a poet may argue with traditional Judaism in one poem and celebrate it in another.

To take a closer look at the history of Jewish poetry by American women, then, is to bring together a collection of poets rarely considered to have anything to do with each other. There is, however, a common thread: The poets share a sense of marginality, of viewing the world from outside the mainstream. Jewish women’s poetry is often transformational, whether it is from within the Jewish world, or in American society at large. Writing from the margins—as Jews, as women—these poets often become the modern equivalent of prophets, critically evaluating and condemning existing circumstances and envisioning better ones. It is worth noting how many Jewish women poets write with a strong sense of social responsibility, a desire to create poetry that can shape reality, perhaps drawing on the Jewish teachings of tikkun olam [repairing the world]. In addition, the poet’s place on the outskirts of literary movements and circles has led in many cases to greater innovation and experimentation.

Emma Lazarus and Nineteenth-Century Poets

Most scholars name Emma Lazarus as the first American Jewish poet, male or female, to be recognized by mainstream America. Born in 1849 to an established American family, Lazarus differed from many other Jewish women poets of her time due to her privileged background and the support of her influential father. Her early poems did not reflect a Jewish awareness but were rooted in classical texts and clearly inspired by the great male poets of her time. The collection of poems that proudly pronounced Lazarus a Jewish poet was Songs of a Semite. Published in 1882, the book coincides with the influx of Russian immigrants to America in response to harsh pogroms, an event that profoundly affected Lazarus.

The poetry of Emma Lazarus embraced the many diverse and often contradictory parts of her identity—the American citizen praising tolerance and liberty, the secular Jew concerned about a Jewish homeland as well as growing antisemitism at home, and the woman who, “late-born and woman-souled,” chose a career in writing over marriage. Despite her traditional use of poetic form, she was in many ways a forerunner to the vocal activism of Jewish women poets writing in the 1960s and 1970s.

Lazarus is best known for her poem “The New Colossus” (1883), engraved at the base of the Statue of Liberty. Most Americans are familiar only with “Give me your tired, your poor, / Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” but the poem as a whole hints at the three parts of Lazarus’s identity—the powerful figure of the welcoming mother, the theme of exile, and the affirmation of America’s tolerance. The Statue of Liberty becomes “A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame / Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name / Mother of Exiles.” It may be that Lazarus’s genuine belief in America as the land of opportunity allowed her to embrace her Jewish heritage publicly, partly out of an idealist hope that America could not harbor antisemitism, and partly as a defiant stand in the face of antisemitism when she could no longer ignore it.

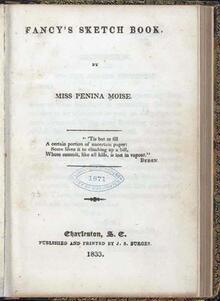

While Lazarus remains the best-known Jewish woman poet of the nineteenth century, there were many other Jewish women writing poetry, many of whom did not venture beyond traditional Jewish themes. Diane Lichtenstein’s book Writing Their Nations: The Tradition of Nineteenth-Century American Jewish Women Writers (1992) was the first book to examine critically the writing of early Jewish women poets. Lichtenstein views the poets in the context of American and Jewish cultural myths, making the claim that these poets attempted to synthesize the American and Jewish ideals of womanhood. Penina Moïse (1797–1880) wrote the first Jewish hymnal, as well as one of the first volumes of poetry published by a Jew in America, Fancy’s Sketch Book (1833). Her poem “Daughters of Israel” calls, as Lazarus did, Jewish women into action, but here it is a battle to maintain and uphold traditional Jewish roles. “Wife! mother! sister! on ye all / A tender task devolves / Child husband, brother, o ye all, / To nerve their best resolves.” She also wrote poems reflecting the immigrant’s dream of acceptance in the New Land. That there was a need for lines such as “Oh! not as Strangers shall your welcome be / Come to the homes and bosoms of the free” suggests wishful thinking, an attempt to comfort and inspire those new immigrants who, perhaps, did not receive such a warm welcome. It is difficult to know whether poets like Lazarus and Moïse wrote these poems out of pride and conviction, or out of fear of antisemitism and a desire, conscious or not, to align with the American side.

Lichtenstein includes many lesser-known poets in the “tradition” of Jewish women’s poetry. Rebekah Gumpert Hyneman (1812–1875) wrote poems in praise of biblical women, celebrating rather than questioning them, as modern poets would later begin to do. Octavia Harby Moses (1823–1904) was another poet who accepted her position as the traditional Jewish mother and wife. In the 1890s, Jewish women’s poetry gained greater prominence, as Jewish women took advantage of the expanded freedoms offered to all white American women.

Jewish Women’s Poetry in Yiddish

There was, of course, another group of women poets writing in the early twentieth century who offered tremendous innovations of musicality and form. Immigrating to the United States from Eastern Europe, these poets wrote poems in Yiddish clearly inspired by modernist trends in Europe. Despite the nonpolitical nature of most Yiddish American poetry by women, socialist and communist journals often published their work, as well as the elitist literary journals of the Yunge and Inzikh movements. While women writers hovered on the fringes of the Yunge, a literary movement that emphasized personal voice over nationalistic rhetoric, experimentation with mood and language over traditional form, and the aesthetic beauty of the poem independent of political associations, they incorporated many of its values. In fact, women poets had an ironic advantage. Their marginal position allowed them the freedom to explore unique variations of meter and sound as well as personal subject matter, surpassing some of the better-known male poets in originality and intensity of mood.

Anna Margolin (1887–1952) and Celia Dropkin (1888–1956) were two of the most significant and inventive women poets writing in Yiddish. Margolin’s poetry characterizes the modernist leanings of Yiddish American poets in its attention to form, sound, and intimate subject matter. Mysterious, impassioned, and linguistically complex, her poems mirror the writing of European modernists with their references to classical texts. She herself lived a modern life unrestricted by traditional roles; she had several lovers and allowed her son to be raised by his father. While Celia Dropkin’s life was more suited to traditional family values—she married and raised five children—her poetry was not. Her poetry seemed to dance along the edge of the acceptable, with an almost erotic fascination with the dark and dangerous. In “I Am a Circus Lady,” the speaker of the poem dances between knives, lured by the danger of touching them, of falling. Fradel Shtok (b. 1890) was another poet of exceptional originality, although her work is more difficult to find in translation. She couched striking imagery in a brashly erotic tone and highly experimental poetic forms.

Yiddish women poets were generally well-versed in European literary trends, but they also lived their daily lives immersed in the rich cultural texture of yiddishkeit. They were twice alienated—as immigrants to America and as women on the outskirts of Yiddish politics and the literary elite. Thus their poetry reflects an even greater complexity in terms of identity than that found in the poetry of the early poets writing in English. Yiddish women poets grappled with their changing relationship to traditional Jewish roles as well as to a traditional God. Kadya Molodowsky (1894–1974) was already an established poet when she immigrated to America in 1935. Respected for her poetry, journalism, and scholarship, she fought through her poetry against the condescending treatment of women poets by the male-dominated intellectual circles of the time. Playing off the concept of the Jews as the chosen people, in the poem “God of Mercy,” she asks God in an ironic, but seriously plaintive tone to “choose another people.” While not doubting the existence of God, she is able to argue with the injustice and tragedy God allows the Jewish people to suffer: “O God of Mercy / For the time being / Choose another people. / We are tired of death, tired of corpses, / We have no more prayers.” She asks God to “grant us one more blessing—/ Take back the gift of our separateness.”

Malka Heifetz Tussman (1893–1987), whose work was published in Insikh, the journal of the radical Introspectivists, also engaged in a dialogue with God through humor as well as debate and plea. She speaks to God intimately, finding connection to the divine through nature. To her, a sunset is a “Godset.” She views the creative process of the poet as a divine process and at one point writes simply that “The Holy One is a poem.” This intimate and playful battle of words captures a uniquely Yiddish approach to the divine—celebrating, teasing, and questioning in the same breath.

In addition to the more literary poets, many Yiddish women chose to write politically and socially motivated poetry for communist presses. These poets were less concerned with God and poetics and more concerned with the need to change the place of women in society. Speaking out against the oppression of women, poets such as Esther Shumiatcher, Sara Barkan, and Shifre Weiss wrote poetry designed to motivate and inspire.

When looking at the Yiddish poetry of women in America, it is important to acknowledge the Jewish women, many of them poets themselves, who have made Yiddish poetry the subject of literary criticism through research and translation. Given the emphasis on sound and form, it is unfortunate that most Jewish readers are unable to read the poems in their original language. Norma Fain Pratt, Kathryn Hellerstein, Adrienne Rich, Ruth Whitman, and Marcia Falk have done invaluable work in making these poems accessible through careful translation and scholarship.

Modernist Poets in the Twentieth Century: Gertrude Stein and Muriel Rukeyser

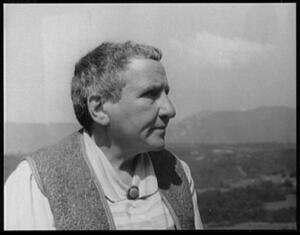

The well-known modernist poet Gertrude Stein shares in common with the Yiddish poets a devotion to stylistic experimentation. But how is it possible to compare this first major poet of the twentieth century to her predecessors, poets such as Lazarus and Moïse, who exemplified the ideals of Judaism, womanhood, and America? Rather than attempting to balance or reconcile the Jewish, female, and American aspects of her identity, Stein chose to disregard them. She lived her life in antithesis to all expectations and stereotypes—a Jew who bordered on antisemitism, a lesbian who played out the traditional male role of husband to Alice B. Toklas, and an American who chose to live and write in Paris. She was also an art collector and hostess of a successful salon, maintaining close connections with painters and composers as well as poets. As the child of prosperous German Jewish immigrants, this appreciation for art and culture was itself a trait of the Jewish upper middle class from which she came. Yet Stein was determined to forge her own unique path. Her defiance of traditional rules and boundaries was applied with equal enthusiasm and conviction to her poetry. She was one of the greatest modernist writers of her time, experimenting with form, language, and musicality, attempting to rid herself of nouns as she rid herself of any preconception of how she must behave. It was precisely her ability to follow her own unique path that earned her a prominent place in American literary history.

Naomi Replansky, another noteworthy Jewish poet of the early twentieth century, did not achieve such fame. Her first book of poems, Ring Song, was not published until 1952, although it included poems written as early as 1934, when Replansky was just sixteen years old. Replansky wrote lyrical, carefully worded poems that belied their intensity. A few of these poems centered around Jewish themes, such as the poem entitled “The Six Million,” which recounts a godless Holocaust, but other poems reflect a related theme of otherness. In “Housing Shortage,” published in The Dangerous World, the speaker of the poem feels she is taking up too much emotional space. “I tried to live small / I took a narrow bed. I held my elbows to my sides. I tried to step carefully / And to breathe shallowly / In my portion of air / And to disturb no one.” Replansky was not a prolific writer, publishing only two collections, but her accomplished voice and quietly intense response to the Holocaust are worth further exploration.

Muriel Rukeyser (1913–1980), one of the most significant Jewish American poets in history, grappled fully and passionately with all aspects of her identity. Hers is not only the story of a tremendously gifted, driven, and prolific writer, but it is the story of twentieth-century America, told from the point of view of one Jewish activist. Born on the eve of World War I, Rukeyser witnessed and condemned a host of injustices around the world. Despite Rukeyser’s contribution as a modern writer, her story is also one of invisibility; she is rarely included in the all-male roster of modernists such as Wallace Stevens, William Carlos Williams, and Ezra Pound. Her inventive writing style, range of themes, and unique capacity for embracing contradiction make her work difficult to classify, and many critics have dismissed her for that reason. Jewish poets such as Adrienne Rich and Denise Levertov, however, praise Rukeyser as a mentor and role model. Rich, in her introduction to A Muriel Rukeyser Reader (1994), writes:

To enter this book is to enter a life of tremendous scope, the consciousness of a woman who was a full actor and creator in many ways. Muriel Rukeyser was beyond her time—and seems, at the edge of the twenty-first century, to have grasped resources we are only now beginning to reach for: connections between history and the body, memory and politics, sexuality and public space, poetry and physical science, and much else.

Rukeyser, like Lazarus and many of the poets to follow, was not only a poet but a;sp a brilliant and persuasive essayist. In addition to publishing fifteen collections of poetry, Rukeyser wrote numerous articles and books of prose. But writing in the mid-twentieth century as a lesbian, she chose very different means of expressing the conflict between her Jewish and female identities. Her first book of poems, Theory of Flight, written when she was twenty-one, was awarded the Yale Younger Poets Prize. Already in this early collection she writes in her “Poem of Children,” “Breathe-in experience, breathe-out poetry.” This is precisely what she continued to do in her work, chronicling her personal experiences alongside those of the entire planet. Her rich and inspiring life led her to Alabama to report on the Scottsboro trial, to Spain on the eve of Civil War, and to North Vietnam to speak out in the 1960s. Every one of her political actions was recorded in poetry. “The Book of the Dead,” a poem written in response to miners in West Virginia, represents a new way of writing poetry, in which Rukeyser’s voice intertwines with the minutes of meetings, workers’ letters, graphs and equations, stock quotations, and even X-rays. Rukeyser saw poetry as a necessary way to combat the terrible silence of nations in the face of World War II and other tragedies.

While she experimented with a range of traditional and new forms, her most innovative work captures the rapid, disjunctive movements of modern life. Rukeyser herself compared this type of writing to the collage of camera angles used in film. In her book The Life of Poetry (1949), Rukeyser was able to contain the full multiplicity of the self—vast, paradoxical, and infinitely rich. The book not only offers up a philosophy of what poetry can mean, but also a unique perspective on what poetry can do. As Rich wrote, “What does poetry have to do with democracy? Read it here.”

Muriel Rukeyser wrote openly of her experiences as a woman and a Jew, tossing her Jewish identity into the complex range of ideas present in her poetry. The poem “Letter to the Front,” published in 1944, merges the atrocities of the Holocaust with a long list of political injustices occurring during her lifetime. “To be a Jew in the twentieth century,” she writes, “Is to be offered a gift.” But the second stanza continues, “The gift is torment.” What makes being a Jew in the twentieth century “torment”? That it requires living as the whole self, feeling a sense of responsibility for all those in need, and daring to “live for the impossible.” Rukeyser is a key poet in the course of Jewish women’s poetry, not only because her poetry stands as a memoir to a dramatic and volatile era in American history, but because Rukeyser so willingly accepted the “gift” of her Judaism at a time when, as Stein demonstrates, it was possible to ignore it.

Adrienne Rich: Sexual Identity and Politics

It is hard to imagine a feminist anthology or university course that would not include the poetry of Adrienne Rich. Much of the praise she extended to Rukeyser’s body of work could be applied to her own. She, too, was a passionate and prolific writer, unleashing the possibilities of poetic form and subject matter to meet her needs. Like Rukeyser, she took on the role of poet-prophet, refusing to shy away from the most difficult and painful events and emotions. And yet the all-consuming passion with which she wrote and lived, sometimes manifesting as rage, sometimes love, suggest that Rich was hopeful about our capacity to effect change. Her involvement in the political and feminist movements of the 1960s led her to write with eloquence about the relationship between the personal and political, power and powerlessness. Much of Rich’s poetry was an attempt to break down the barriers between sexual identity and politics, “between Vietnam and the lover’s bed.” The poem “Diving into the Wreck,” which marked a turning point in Rich’s poetry, perhaps best describes the way in which Rich bravely delved into the “wreck” of flawed societal structures that reside around and within her: “I came to explore the wreck. / The words are purposes. / The words are maps. / I came to see the damage that was done / and the treasures that prevail.”

While Rich is best known for the fragmented, often angry poems inspired by her changing politics in the 1960s and 1970s, her poetry had a very different beginning. Like Rukeyser, she was awarded the Yale Younger Poets Prize in her early twenties. This first collection of poems, A Change of World (1951), was carefully shaped and structured, the poems neatly worded and understated. Even in this early work, however, Rich was beginning to write about the hierarchy of male-female roles in poems such as “Aunt Jennifer’s Tigers,” but through implication and metaphor rather than direct statement. That Rich began writing in the tight, controlled forms of modern American writing in the 1950s suggests that the open, fragmented style of her later work was equally controlled and deliberate, a style chosen by Rich to encompass a rage and a vision that could no longer be contained in more traditional forms.

What makes Rich such a central figure in terms of Jewish American poetry is that she wrote openly about her divided self in her later work. Rich pushed the already marginal status of the Jewish American women even further than her predecessors, presenting herself as the half-Jewish American woman, ostracized by and struggling to come to terms with both halves. In an essay in Nice Jewish Girls: A Lesbian Anthology (1982), Rich challenged herself to confront her relationship to the Jewish part of her heritage and identity. The essay “Split at the Root: An Essay on Jewish Identity” grapples with Rich’s relationship with her secular Jewish father, her own latent antisemitism, and her process of growing awareness and commitment as a Jew. Her father was relatively silent about his Judaism, and Rich grew up in a Christian environment of proper manners and hidden racism. “Sometimes I feel I have seen too long from too many disconnected angles: white, Jewish, anti-Semite, racist, anti-racist, once-married, lesbian, middle-class, feminist, exmatriate southerner, split at the root—that I will never bring them whole.”

Rich’s prose work can articulate and break down the inconsistencies of the whole self, but only a poem can bring them together in one fragile effort of will, like a broken vase whose pieces are put back together without glue, threatening to shatter at any moment. In a longer poem, “Sources,” Rich engages in a poetic battle with her contradictory roots. The phrase “split at the root” forms the haunting chorus of this difficult poem; “From where does your strength come, you Southern Jew? / split at the root, raised in a castle of air?” Rich holds her life up against the Jews of the Holocaust—“All during World War II / I told myself I had some special destiny ... there had to be a reason / I was growing up safe, American / with sugar rationed in a Mason jar” and the Zionist women who forged a new life in Palestine—“socialists, anarchists, jeered / as excitable, sharp of tongue / too filled with life / wanting equality in the promised land,” trying to map out her place among them, a way to connect. In another poem in the same collection, “The Day of Atonement, which falls on the 10th day of the Hebrew month of Tishrei and is devoted to prayer and fasting.Yom Kippur 1984,” Rich does not distinguish her Jewish identity from social consciousness. She interrelates a move cross-country, the renewal and communal spirit of The Day of Atonement, which falls on the 10th day of the Hebrew month of Tishrei and is devoted to prayer and fasting.Yom Kippur, and the daily injustices she reads in the paper into a textured collage reminiscent of Walt Whitman. “What is a Jew in solitude?” she asks, then immediately extends the question: “What is a woman in solitude: a Queer woman or man?”

While the impetus of her writing was often raw emotion—need, anger, sorrow, love—it was examined from a highly intellectual perspective that exposes the pain, but also distances from it. Mind and heart, like Jew and gentile, woman and American, personal and political, wrestle in her poems. Although Rich’s background may be more ambivalent than some other Jewish writers, her work is profoundly Jewish in that she dared to ask the question, and to take responsibility for a heritage she must seek out for herself. She became a strong advocate of peace between Palestinians and Jews in Israel and cofounded the Jewish women’s journal Bridges.

Feminist Jewish Women’s Poetry

Many Jewish poets writing poetry from the 1970s to the present have aligned themselves with the feminist movement and believed in the poetic power to make changes in terms of gender equality and political justice. Denise Levertov shared Rich’s tenuous relationship with her Jewish heritage, feminist approach, and sense of social responsibility, but these elements enter her poetry in a more subtle way. Her father was raised a Hasidic Jew, then converted to Christianity before she was born. Her Irish mother treasured story, magic, and mysticism. This connection to the spiritual and to myth is evident in Levertov’s poetry. Levertov wrote several poems drawing on biblical texts. “The Jacob’s Ladder,” which is shaped like a series of steps, uses the biblical image as metaphor. In Levertov’s version, the ladder is made of stone, and the angels must hop down, while “a man climbing / must scrape his knees.” This interchange of human effort and spiritual visitation becomes a metaphor for writing poetry. “Wings brush past him. / The poem ascends.”

Other feminist writers, such as Erica Jong and Marge Piercy, wrote poetic commentary on the relationship between women and men in society. Many of Piercy’s poems revolve around cultural notions of beauty, and the tension between the individual identity and societal expectations. In “Barbie Doll,” the “girlchild,” criticized by a classmate, eventually cuts off the offending body parts and dies. Made to look beautiful in her coffin, the guests exclaim over how pretty she looks. Other fiction writers who have also published books of poetry include Grace Paley and Cynthia Ozick.

Piercy and other feminist poets have attempted to rewrite the cultural myths held by the society in which they live. But the changes in the 1970s moved beyond a heightened awareness of universal political and social injustice. The celebration of ethnic culture and emphasis on individual awareness and discovery in the past few decades have drawn many Jewish poets to look openly at what makes them Jewish, examining their relationship with the past as well as present Jewish community.

Holocaust and Yiddishkeit Poetry

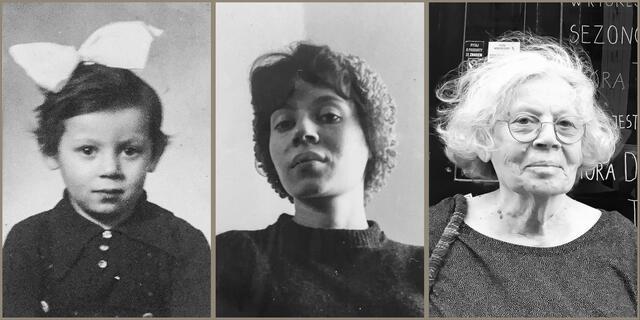

Poets such as Myra Sklarew and Irena Klepfisz write poetry that attempts to repair the ties to ancestors and the culture of Eastern European Jewry severed by the Holocaust. Other poets write from the perspective of outsiders, not to America, but to the land of Israel. Irena Klepfisz is a powerful and significant voice in Jewish women’s poetry. As a lesbian Jewish poet, she writes about themes of feminism and lesbianism, as well as activist poetry about Israel. Her poetry is most notable, however, for her struggles to revive the Yiddish culture that has been lost both through the Holocaust and through assimilation in America. Klepfisz attempts to make peace with the duality of her immigrant status, further complicated by the reality that Yiddish was not, as she was told, her mame loshen [mother tongue], by juxtaposing Yiddish and English on the page in a fascinating dance of dueling identities. These lyrical poems do not translate the Yiddish but engage with it, bringing it back to life and making the poem, like the poet, incomplete without both halves interwoven. She writes that “this Yiddish of mine, this fragmentary language ... might prove worth salvaging and sheltering.” The revival of the Yiddish language, then, is in some way a tribute to the sustaining life force of a culture and people who have survived, and a way for the poet to remember and reach out to them. She expresses this in “Di Rayze Aheym / The Journey Home”:

Zi shemt zikh.

She has forgotten

alts fargesn

forgotten it all.

Myra Sklarew also writes about the Holocaust from a personal perspective. Her poems reflect a playfulness with language even as the content is intensely serious. Those who died in the Holocaust continue to walk through her thoughts and poems. In “Benediction,” she writes, “Sometimes I see them coming / and going along the road / where they were swallowed up / carrying their empty luggage.” Having written seven books of poetry, including From the Backyard of the Diaspora (1976), Sklarew’s greatest accomplishment is the collection entitled Lithuania (1995). The poem “Lithuania,” written in ten sections that interweave Sklarew’s return to the sites of massacres with documentation and story drawn from accounts by Holocaust survivors and Lithuanian citizens, family letters, and diaries, is a moving account of both the suffering and loss of Lithuanian Jewry, and the effort of one Jewish woman in America to record and remember it as her own experience. Sklarew, disturbed by the beauty of the landscapes where such horror took place, writes that “the poem attempts to penetrate beneath the pastoral beauty of these habitations of death, to peel back the layers of earth and time, to touch the places where our people once lived and, by so doing, to touch them.”

Zionist and Anti-Zionist Poetry

American women living in Israel and beyond grapple with their relationship to Israel during times of political tension. The desire for a just and peaceful world wrestles at times with love and support for a Jewish homeland. There are several women poets writing in English in Israel, but the work of Shirley Kaufman, Linda Zisquit, and Rachel Tvia Back is read in America, providing through the intensity of poetry an account of the events and mood of Israel.

Shirley Kaufman is often included in anthologies of contemporary American poetry, though she resides primarily in Israel. One of her most significant and powerful poems, “Looking at Henry Moore’s Elephant Skull Etchings in Jerusalem During the War,” is a long poem that records the fear and alienation of living in Israel in wartime through fragments of image and dream. “There is a way to enter / if you remember / where you came from / how to breathe under water / make love in a trap.”

In the first collection of poems by Linda Zisquit, sparse and elusive poems rest uneasily against a backdrop of war and tension. “When war broke out I was unloosed,” she begins in a sensual and disturbing poem about love entitled “Summer at War,” written in 1982. Zisquit is not only an American Jew living in Israel but a modern Orthodox Jewish woman, coping with the hurt and alienation of being a woman in a male-dominated tradition, revisiting Talmudic and biblical texts. The voice in her poems is distant and restrained, giving a sense of barely controlled emotion. “My body like a poem / admires itself, tries to make itself / perfect,” she states in the poem “In Hebrew the Word Compassion Is Plural for Womb.” Rachel Tvia Back presents a newly emerging voice, experimenting with language and collage to transpose the experiences of the Gulf War onto the page. In “Notes from a Sealed Room,” the room becomes a cave, a womb: “place of hiding and hidden (heart’s / cave, heart’s caution: calcareous regions).” Women writers living in America also write poems about Israel, some describing how it feels to be there, others writing from a more political point of view. The anthology Without a Single Answer: Poems on Contemporary Israel (1990), edited by the poets Elaine Marcus Starkman and Leah Schweitzer, includes beautifully written poems on a variety of perspectives and from a surprising range of voices, such as a poem by Julia Vinograd, a Berkeley street personality and poet, on a Jerusalem she has never seen.

Religious Tradition, Midrash, and Spiritual Poetry

As women poets are turning their attention toward their heritage and culture, they are taking a new look at traditional texts. The poet Deena Metzger, inspired by quests for spiritual fulfillment, also drew on the fertile environment of the 1970s. Her spiritual poetry is framed within a primarily Jewish mystical perspective, drawing on the teachings and language of the Kabala. Through poetry, Jewish women have both criticized and reconnected with the texts and rituals that excluded them for so long. A growing trend, one that is rooted in the English and Yiddish poetry of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, is for Jewish women poets to add their voices to the sacred texts of Judaism through poetry that takes the form of A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).midrash on biblical sources in the form of stories.

Alicia Ostriker (b. 1937) is one of the more playful experimenters with poetic midrash. Ostriker has contributed to the face of women’s poetry in America through her feminist critiques and political poetry. Her critical work Stealing the Language: The Emergence of Women’s Poetry in America (1986) analyzes an astounding range of poetry by women, drawing connections between them and highlighting their compromised position in the essentially male literary world. Ostriker’s midrash inspired poetry wages a similar war within the boundaries of Jewish tradition. These poems are angry and forthright but are often laced with humor and absurdity. Retelling the story of the covenant with Abraham, for example, she writes from the perspective of a modern-day Abraham, reading over a slightly fishy contract. The poem “The Story of Abraham,” included in David Curzon’s anthology Modern Poems on the Bible (1994), presents a bold headline that paraphrases the biblical rendition of the blessings promised to Abraham. But the small print adds several conditions, including “a mark of absolute / Distinction,” circumcision. When Abraham interrupts, saying, “I’d like to check / Some of this out with my wife,” God responds: “NO WAY. THIS IS BETWEEN US MEN.” Ostriker’s humorous but telling re-envisioning of biblical text is fully explored in her book The Nakedness of the Fathers (1994), a book that integrates poetry and critical prose.

Ostriker’s midrashic poem speaks through the voice of a man, but many poems by Jewish women allow the women in the Bible, who often play a secondary role to the men, a chance to speak, sometimes for the first time. The act of re-creating the voices of these women provides a new and rich connection to biblical sources for women by either allowing the contemporary woman to enter into the biblical story or drawing the biblical character into a modern context. The titles of recent anthologies of Jewish women’s writing are evidence in themselves of this trend. One anthology, entitled Sarah’s Daughters Sing (1990), brings together poems by Jewish women writing in America and beyond. It is an important work because it draws together poetry on Jewish themes, such as poetic midrash, and poetry by Jewish women on non-Jewish themes, such as love and the home. The anthology of work by lesbian Jewish writers, edited by Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz and Irena Klepfisz, alludes to the forgotten sister of the male leaders of the twelve tribes of Israel in its title, The Tribe of Dina (1986). And the Jewish women’s magazine Lilith celebrates in its title the reclaiming of the first wife of Adam. Seen through male eyes as a traitor, temptress, and demoness, Lilith is hailed by contemporary women as a feminist visionary. Women poets rescue the figure of Lilith, reinvent Eve and the matriarchs, and take over the role previously granted to Adam to observe and name the world around them.

In 1984, Shirley Kaufman wrote a poem in which the biblical Sarah and Hagar become two women living in modern Jerusalem. Entitled “Déjà Vu,” the poem imagines a meeting at the Dome of the Rock, the place Muslims believe Abraham brought Ishmael to be sacrificed. Sarah is “showing the tourists with their Minoltas / around their necks the place / where Mohammed flew up to heaven,” while Hagar prays in the women’s section.

They bump into each other at the door,

the dark still heavy on their backs

like the future always coming after them.

Sarah wants to find out what happened

to Ishmael but is afraid to ask.

Hagar’s lips make a crooked seam

over her accusations.

The juxtaposition of the two stories provides a powerful commentary on the lives of Jewish and Palestinian women in contemporary Israel, while adding a creative and beautifully written midrash to the rabbinic commentaries.

Poets such as Chana Bloch and Linda Pastan do not confront directly their Jewish selves in their work, but their Jewish identities and love of biblical text are simply an integral part of who they are and what they write about. Bloch, who is also well known as a translator of Israeli poets, writes poems that have been whittled down to the core like the smallest Russian doll in her poem “The Family.” Writing about family and personal experience, Bloch is able to enter the remembered world of the child. In a poem recalling the small joys of childhood, she asks innocently, “If we were so happy / why weren’t we happy?” When writing on biblical themes, Bloch imaginatively enters biblical texts, making startling leaps of imagery with grace and skill. Her midrashic poems are not political commentaries about the stories, but paths for the reader to follow into the story itself, captured through sound, mood, and image.

Linda Pastan’s poetic world is also a small one, as she keenly observes and delights in the simple pleasures and common experiences of her life. She describes the everyday, from the stationary bicycle to an article of clothing, with such a fresh approach and skilled crafting of language that it becomes memorable and meaningful. “Long after Eden, the imagination flourishes with all of its unruly weeds.” Among these daily experiences, she writes of setting the A seven-day festival to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nissan. Also called the "Festival of Mazzot"; the "Festival of Spring"; Pesah.Passover table and visiting Jerusalem, and constantly draws hints of biblical story into her poems. A poem entitled “Lumberjacks” views the cutting down of the forest as a symbolic destruction of Eden, as Eve watches their work until “even the complicitous apple was felled, and the smell / of sawdust was like death / in the nostrils” (An Early Afterlife).

Rejection of Jewish Themes in Poetry

Two of the most significant women poets of the 1980s and 1990s, Louise Glück and Maxine Kumin, write poetry that renders their Jewish backgrounds practically invisible. This is not to say that they reject their Jewish heritage, only that it does not appear as a theme in their poems. Louise Glück, who won the Pulitzer Prize for The Wild Iris (1992), does explore biblical mythology along with Greek, but does not do so from a particularly Jewish perspective. Glück’s tight, meticulously crafted, and lyrical poetry uses paradox and deliberate ambiguity to describe the “thrust and ache” of the human condition. An earlier poem, “The Garden,” encompasses the human fear of birth, love, and burial in the creation myth. Her later collection, The Wild Iris, returns to the scene of the garden, but in this work it is the modern-day garden superimposed on the mythological. In this poem, everyone speaks—the gardener, the flowers, even a God who is voiced by seasons and changes of weather. Despite allusions to Eden and Moses, the structure of the book revolves around the daily Christian prayers of Matins and Vespers. It is an ambitious and moving work, merging the eternal resonance of the mythological garden with the present-tense urgency of caring for an actual garden, in which there is constant change, and all movement is overshadowed by inevitable winter.

Although she was “raised on the Old Testament,” the closest thing to God in the poems of Maxine Kumin is the natural world, which she turns to for signs of survival and regeneration. Often mesmerized by the everyday, Kumin places humans, animals, and vegetables on equal footing in her poems. Ordinary places become magical, the kitchen “a harem of good smells / where we have bumped hips and / cracked the cupboards with our talk.” Like Pastan, the gift of her poetry lies in the balance of powerful observation and skilled shaping of line and experience. Inside a pea pod, “nine little fetuses / nod their cloned heads” (“The Pea Patch”).

Jewish Prayer as Poetry

While Jewish women can forge new links with sacred text through poetic midrash, Jewish women poets have returned to the timeless ritual of prayer. Poets such as Ruth Whitman in her collection The Marriage Wig (1968) challenge traditional women’s roles and ritual in the Jewish community. The need for new liturgy to accompany changing approaches to women’s ritual has led women rabbis and leaders to seek out poems and songs to replace and supplement traditional prayers. There is traditionally in Judaism a fine line between poetry and prayer, and Jewish women in recent years have crossed over it. A diverse collection of poems edited by Marcia Cohn Spiegel and Deborah Lipton Kremsdorf, Women Speak to God: The Prayers and Poems of Jewish Women (1987), contains in one book Miriam’s Song of the Sea, poems by Yiddish and English poets that address, question, and rebel against God, and newly written prayers by women for a variety of occasions. Marge Piercy has written several poems that work as more inclusive and relevant alternatives to traditional prayers, such as the Lit. "standing." The primary element of each of the three daily prayer services.Amidah [the central section of prayer at each service].

Marcia Falk’s Book of Blessings: New Jewish Prayers for Daily Life, the Sabbath and the New Moon Festival (1996), renders poetry and prayer nearly indistinguishable. It may seem strange to include a prayer book in a survey of Jewish women’s poetry, but this siddur is also a collection of poems. Falk’s quiet, meditative poems, along with her lyrical translations and adaptations of Israeli and Yiddish poets and traditional psalms, serve as prayers and meditations. Even her genderless re-creations of blessings demonstrate a movement and lilting lyricism, clearly written through the eyes and ears of a poet. Poetic devices such as line breaks, alliteration, and rhyme are used when necessary to highlight the theme of each blessing. Marcia Falk has been noted for her poetry and scholarship, as well as her translations of the Hebrew poet Zelda and the Yiddish poet Malka Heifetz Tussman, but this work may prove to be her crowning achievement. It reminds us of the power of poetry to lift us out of the material world into a more sacred and awesome space, and makes prayer more relevant and accessible to contemporary Jews, particularly women, who have been alienated by traditional liturgy.

Legacy and Contribution to American Literary History

The contributions of Jewish women poets to American literary history and political activism, as well as to the enrichment of Jewish culture and practice, are astounding. With the recent flourishing of Jewish women poets, it is impossible to name them all. Feminist Jewish journals such as Lilith and Bridges feature their work, as does the Jewish literary journal Agada, edited by Reuven Goldfarb, and the politically based magazine Tikkun, of which Marge Piercy is poetry editor. But these glimpses at the poetry of Jewish women in feminist anthologies and Jewish journals do not tell the whole story. A definitive anthology of poetry by Jewish American women poets has yet to be published.

ANTHOLOGIES OF JEWISH WOMEN POETS

Kaye/Kantrowitz, Melanie, and Irena Klepfisz, eds. The Tribe of Dina: A Jewish Women’s Anthology (1986).

Spiegel, Marcia Cohn, and Deborah Lipton Kremsdorf. Women Speak to God: The Prayers and Poems of Jewish Women (1987).

Wenkart, Henny, ed. Sarah’s Daughters Sing (1990).

LITERARY CRITICISM

Baskin, Judith. Women of the Word: Jewish Women and Jewish Writing (1994).

Gittenstein, R. Barbara. “American-Jewish Poetry: An Overview.” In Handbook of American-Jewish Literature: An Analytical Guide to Topics, Themes, and Sources, edited by Lewis Fried (1988).

Hellerstein, Kathryn. “Poetry.” In “Jewish American Writing.” Oxford Companion to Women’s Writing in the United States, edited by Cathy Davidson and Linda Wagoner-Martin.

Lichtenstein, Diane Marilyn. Writing Their Nations: The Tradition of Nineteenth-Century American Jewish Women Writers (1992).

Ostriker, Alicia Suskin. Stealing the Language: The Emergence of Women’s Poetry in America (1986).

Stern, Gerald. “Poetry.” In Jewish American History and Culture: An Encyclopedia (1992).