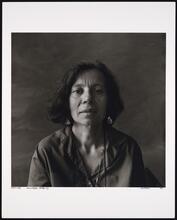

Fradel Shtok

Fradel Shtok’s Yiddish poetry and prose is distinctive for its treatment of the inner sensual lives of Jewish women. Immigrating to America from the Galician shtetl of Skale at age seventeen in 1907, she published poems and short stories in several anthologies and literary journals, especially those of the literary group Di Yunge [The Young Generation]. Although she showed great promise as a poet and prose writer, she was discouraged by the unenthusiastic reception of her collection of short stories by leading critics in New York in 1919 and withdrew from the Yiddish literary scene. No collection of her poetry ever appeared. In recent decades, feminist poets and literary historians have rediscovered Shtok’s work and made it known to English-language readers through translation and critical interpretation.

Early Life and Writing

Fradel Shtok holds a place among the pioneers of modern Yiddish literature for her treatment of the inner sensual lives of Jewish women. Although her work showed great promise, her career as a Yiddish writer was brief. Very little biographical information is available about her. Born in Skale, Galicia, in 1890, she was a lively child, musically talented and academically gifted, but her early childhood was marred by the death of her mother when Shtok was two years old. A few years later, her father, Shimen, was sent to prison for his involvement in a murder and died there when Shtok was ten. Thereafter, she was raised by an aunt.

Immigrating to New York in 1907, Shtok published poems and short stories in several anthologies and literary journals, especially those of the literary group Di Yunge [The young generation]. In 1914, eight of her sonnets were published in the anthology Di Naye Heym [The new home], which she co-edited with Yoysef Opatoshu, Y. Y. Shvarts, and Yoysef Rolnik. In 1915, her essay “Vos iz poezye?” [What is poetry?] appeared in Moyshe Leyb Halpern’s anthology Fun mentsh tsu mentsh: a zamlbukh far poezye [From person to person: an anthology of poetry]. She contributed five poems and five sonnets to Moyshe Basin’s landmark anthology Antologye fun Finf Hundert Yor Yidishe Poezye [Anthology of five hundred years of Yiddish poetry] (1917). Shtok was one of the first poets to write sonnets in Yiddish. According to literary historian Avrom Tabatshnik, she was the first woman poet who stood “at the same artistic level as the male poets of her era. If she had only written the five sonnets that were included in Basin’s anthology, her place in Yiddish poetry would have been assured.”

In 1919, Shtok published a collection of thirty-eight stories entitled Gezamlte Ertseylungen [Collected stories]. The stories are set in Eastern Galician (Yiddish) Small-town Jewish community in Eastern Europe.shtetlekh of Shtok’s childhood and the Jewish immigrant milieu of early twentieth-century New York. They portray the inner lives of characters constrained by the social strictures of traditional Jewish society in the Old World and by proletarianization in the New. Themes of female eroticism and sexual repression are prominent in stories with female protagonists, while male characters grapple with gendered expectations of men in changing social and economic circumstances. Shtok’s clear-eyed view of the constraints imposed on individuals by the circumstances of ibershikhtung (class restructuring) informs her modernist storytelling.

Critical Response in the United States

Responses from critics to Gezamlte Ertseylungen were mixed. Reviews by three leading critics appeared in 1919 and 1920. Writing in Der Tog [The day] in December 1919, the poet Aaron Glanz-Leyeles acknowledged Shtok’s unique talent, praising the individuality in her writing style and use of language, but arguing that, as a whole, the collection was monotonous. Referring to Shtok several times as a beginning writer, he complained that all of her stories were set either in the shtetl or the sweatshop and advised her to “crawl out” of these milieus if she possibly could. Shtok was said to have been deeply angered by Glanz’s review.

An even more unsympathetic review of Gezamlte Ertseylungen by the radical critic Moissaye Olgin appeared in the socialist weekly Di Naye Velt [The new world] in January 1920. Olgin charged Shtok with taking a condescending attitude both toward the characters in her stories and her reading audience and writing with detachment and pessimism. He likened her portrayals of characters to a biologist’s examination of microbes in a petri dish.

Writing in the socialist literary journal Di Tsukunft [The future] in October 1920, Shmuel Niger praised Shtok’s “half-humorous, half-ironic” style and language, but he seemed to damn the collection with faint praise, noting the similarity among the characters, all of whom are dreamers who “seek to throw off the yoke of ordinary dailiness by attaching themselves to a dream or a fantasy in order to brighten the grayness of their real existence.”

Shtok’s collection appeared at a moment when Yiddish writing was developing in radically new directions. With fellow modernist poets Yankev Glatstein and Nokhem Borekh Minkov, Glanz-Leyeles had co-authored the Introspectivist Manifesto in 1919, making a sharp break with the poetics of Di Yunge, the literary trend with which Shtok had associated herself. In January 1920, he wrote: “(For the poet), words can—and should—become tones and colors only.” In 1918, Olgin had completed a PhD in literature from Columbia University with a dissertation on Russian realism. By 1920, he was deeply involved in struggles within the Jewish socialist movement, which would soon split over loyalty to the newly established Soviet Union. These critics evidently saw no place on the contemporary Yiddish literary scene for Shtok’s eygnartik (original, idiosyncratic) approach to writing. Condescendingly, they sought to correct her errors and set her on a different artistic path.

None of the three critics took note of the innovative thematic content in the collection Gezamlte Ertseylungen—namely, Shtok’s foregrounding of the inner lives of female characters.

Shtok is reputed to have abandoned writing in Yiddish because of the unenthusiastic critical reception of the book. During the 1920s, she switched to writing in English and published one novel, Musicians Only (1927), which received little critical attention. A handwritten manuscript of a play entitled Der amerikaner [The American] is among the holdings of the Marwick Collection in the Library of Congress. It was copyrighted in 1923, but there is no record of its having been published or produced. [See Zachary M. Baker, Copyrighted Yiddish Plays at the Library of Congress: An Annotated Bibliography (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 2004), 152.]

Critical Response in the Soviet Union and Poland

Shtok’s Yiddish poetry and prose were reviewed by critics in both the Soviet Union and Poland during the 1920s, but it appears she had already withdrawn from the American Yiddish literary scene by the time they became aware of her contributions.

Melekh Ravitsh reviewed Gezamlte Ertsyelungen in the Warsaw literary journal Bikher-velt in 1923. He acknowledged Shtok’s talent but complained that the stories were so light and playful that they created “the aroma of a girl’s bedroom.” He went on to compare the book to an album of well-crafted and finely colored etchings, mainly depicting the heads of girls, brides, and children.

In his groundbreaking 1928 anthology Yidishe dikhterins [Yiddish women poets], Ezra Korman reprinted six of Shtok’s poems and five of her sonnets, recognizing her work as that of an innovative, modernist poet.

In their 1928 handbook entitled Literatur-kentenish, Soviet critics Dovid Hofshteyn and Fube Shames commented briefly on the sonnet form, noting that it requires precise rhyming and rich musicality. They reprinted one of Shtok’s sonnets as an example and credited her with being the first Yiddish poet to write sonnets, a claim later disputed by Avrom Tabatshnik in Dikhter un Dikhtung (1965).

Writing in the Lemberg literary journal Tsushtayer in 1930, Rukhl Oyerbakh (Rachel Auerbach) discounted Shtok’s poetry as derivative of earlier European trends but praised her “original, (nearly) authentic, polished characterizations” of Galician shtetl-dwellers in Gezamlte Ertseylungen. Oyerbakh lauded Shtok for maintaining “a certain artistic distance, in order to reveal the characters’ qualities and not her own.” Apparently unaware of earlier American criticism or of the publication of Musicians Only, Oyerbakh asked what internal and external obstacles had prevented Shtok from publishing in recent years and encouraged her to resume her writing career, noting that her early accomplishments as a prose writer were impressive.

Mysteries of Shtok’s Later Life

There is scant evidence of Shtok’s life and literary activity after the 1920s. United States census and naturalization documents show that she married Samuel (Simcha) Zinn in 1918. An exchange of letters between Shtok (writing as Frances Zinn) and Abraham Cahan in 1942 [in the Archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, Abraham Cahan Collection, part 2] suggests she had recently written several pieces that she hoped to publish in the Forverts. Shtok’s story “A soykher fun fel” (A Hide Merchant) appeared there on November 19, 1942. Apparently, this single publication did not result in renewed interest in her truncated career. No other works by Shtok published after this date are currently known to scholars.

Records of the Rockland State Psychiatric Hospital in Orangeburg, New York, show that Shtok spent her last years there, arriving in or before 1966, and dying possibly as late as 1990.

In recent years, scholars of Yiddish literary modernism have begun to reexamine Shtok’s oeuvre, finding rich material to research and analyze in both her poetry and prose. A fuller exploration of the early critical reception of her work has yet to be undertaken.

WORKS BY FRADEL SHTOK

Poetry

Di naye heym [The New Home]. Edited by Yoysef Opatoshu, Y. Y. Shvarts and Yoysef Rolnik and Fradl Shtok (1914): 8 poems.

Antologye fun Finf Hundert Yor Yidishe Poezye band 2 [Anthology of five hundred years of Yiddish poetry] vol. 2. Edited by Moyshe Basin (1917): 10 poems.

Nyu-York in ferzn [New York in verse]. Edited by Mani Leyb (1918): 1 poem.

Antologye: di yidishe dikhtung in Amerike biz yor 1919 [Anthology of Yiddish poetry until 1919]. Edited by Zishe Landoy (1919): 1 poem.

Yidishe dikhterins – antologye [Yiddish Women Poets - Anthology]. Edited by Ezra Korman (1928): 11 poems.

Fiction

Gezamlte Ertseylungen [Collected stories] (1919).

Musicians Only (1927)

Translations of Shtok’s stories into English

“The Shorn Head” (Opgeshnitene hor) (translated by Irena Klepfisz). In The Tribe of Dina: A Jewish Women’s Anthology, edited by Irena Klepfisz and Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz, 176-179. Boston: Beacon Press, 1989. Reprinted in Jewish American Literature: A Norton Anthology (2001): 291-293.

“The Veil” (Der shleyer) (translated by Brina Menachovsky Rose). In Found Treasures: Stories by Yiddish Women Writers, edited by Frieda Forman, Ethel Raicus, and Sarah Silberstein Swartz, 99-104. Toronto: Second Story press, 1995.

“The Archbishop” (Der erts-bishof) (translated by Joachim Neugroschel). In No Star Too Beautiful: Yiddish Stories From 1382 to the Present, edited by Joachim Neugroschel, 462-469. New York: Norton, 2002.

“Winter Berries” (Kalines) (translated by Irena Klepfisz). In Beautiful as the Moon, Radiant as the Stars: Jewish Women in Yiddish Stories – an Anthology. (2003): 21-27.

“At the Mill” (Bay der mil) (translated by Irena Klepfisz). In Beautiful as the Moon, Radiant as the Stars: Jewish Women in Yiddish Stories – an Anthology, edited by Sandra Bark and Francine Prose, 75-81. New York: Warner Books, 2003.

“A Dance” (A tants) (translated by Sonia Gollance). In In geveb; a Journal of Yiddish Studies (December 2017).

From the Jewish Provinces: Selected Stories (translated by Jordan D. Finkin and Allison Schachter). Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2021). This volume contains translations of 23 stories from Gezamlte ertseylungen: “Di ershte ban,” “A tants,” “Fridrikh Shiler,” “Der ershter patsient,” “Vayse futerlekh,” “A rede,” “Komediantn,” “Vayn,” “Shvester,” “In dorf,” “Bay der mil,” “Dos glezl,” “Der shleyer,” “Hinde Gitls shnur,” “Mandlen,” “Der erts-bishof,” “A shnit,” “A varim-bod,” “Opgeshnitene hor,” “Der bar-boym,” “Nokh a kale,” “Kalines,” “Di kholere,” plus “A soykher fun fel” (published in Forverts November 19, 1942).

Bibliography of criticism published during Shtok’s lifetime

“Fradl Shtok.” Leksikon fun der Nayer Yidisher Literatur 8, no. 608 (1981): 39–45.

Auerbach, Rachel. “Fradl Shtok.” Tsushtayer (June 1930): 39-45.

Glanz, Aaron. “Temperament.” Der Tog (December 7, 1919): 9.

Glatshteyn, Yankev. “Tsu der Biografye fun a Dikhterin” [Toward the biography of a woman writer]. Tog-Morgn-zhurnal. Sunday supplement (September 19, 1965), 14: 7.

Hofshteyn, D., and P. Shames. “Poetik: Elementn fun Ritm un Stil” [Poetics: Elements of rhythm and style]. In Literatur Kentenish (Ershter Teyl) (1928).

Niger, Sh. “Di Ertseylungen fun Fradl Shtok” [The short stories of Fradel Shtok]. Tsukunft (October 1920): 608–609.

Olgin, Moissaye. “Pesimizm” [Pessimism]. Di Naye Velt (January 9, 1920): 16–17.

Ravitsh, Melekh. “Gezamlte ertseylungen fun Fradl Shtok” [Collected stories of Fradel Shtok]. Bikher velt (January-April, 1923): 64-66.

Reyzen, Zalmen. “Fradl Shtok.” Leksikon fun der Yidisher Literatur, Prese un Filologye 4 (1929): 572–574.

Tabatshnik, Avrom. “Fradl Shtok un der Sonet” [Fradel Shtok and the sonnet]. In Dikhter un Dikhtung (1965).

Bibliography of Scholarship Treating Shtok’s Poetry and Prose (1986 to the present)

Fain Pratt, Norma. “Culture and Radical Politics: Yiddish Women Writers in America, 1890-1940.” In Women of the Word: Jewish Women and Jewish Writing, edited by Judith Baskin, 111-135. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1994.

Fain Pratt, Norma. “Fradel Schtok: Memory and Storytelling in the Early Twentieth Century.” In Di Froyen: Women and Yiddish, 85-88. New York: National Council of Jewish Women, 1997.

Gollance, Sonia. “A Dance: Fradl Shtok Reconsidered.” In geveb; a Journal of Yiddish Studies (December 2017): 1-20.

Hellerstein, Kathryn. "Gender and the Anthological Tradition in Modern Yiddish Poetry.” In The Anthology in Jewish Literature, edited by David Stern, 259-280. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Hellerstein, Kathryn. “The Art of Sex in Yiddish Poems: Celia Dropkin and Her Contemporaries.” In Modern Jewish Literatures: Intersections and Boundaries, edited by Sheila E. Jelen, Michael P. Kramer, and L. Scott Lerner, 189-212. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010.

Hellerstein, Kathryn. “The Idea of a Literary Tradition.” In A Question of Tradition: Women Poets in Yiddish 1586-1987. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2014: 1-28.

Klepfisz, Irena. “Fradel Schtok.” In The Tribe of Dina: a Jewish Women’s Anthology, edited by Irena Klepfisz and Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz, 176-177. Boston: Beacon Press, 1986.

Lyubas, Anastasiya. “Gender, Language and Territory: the Tsushtayer Literary Journal in Galicia and the Contributions of Yiddish Women Writers.” Nashim 37 (2020): 163-184.

Schachter, Allison. “Fradl Shtok’s Aesthetic Desire.” In Women Writing Jewish Modernity 1919-1939. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2021.

Literary works inspired by Shtok’s Oeuvre

Klepfisz, Irena. “Fradel Schtok.” In A Few Words in the Mother Tongue: Poems Selected and New (1971-1990). Portland, OR: Eighth Mountain Press, 1990: 228-229.

Fain Pratt, Norma. “What Remains Is Random.” Lilith 17 (Fall, 1987): 26-30.