Jewish Feminist Texts Help Me Get through the Pandemic

Ten months into a global pandemic, after a summer of sorely needed racial justice agitation, post-election anxiety, and sociopolitical upheaval, I am tired. I turned 20 this fall, and I am trying to grow up to be a responsible, purposeful adult in the middle of all this. While the events of 2020 have in many ways buoyed community strength and promoted togetherness, I am struggling to feel connected while combating burnout and staying safe.

But when my burnout reaches its nadir, I find myself drawing strength from a collection of Jewish feminist writings I discovered in my first semester of college. That semester, I wrote a research project about Jewish feminist poetry from the second wave movement. Early in the semester, in my college’s library, I found an anthology copy of a themed 1986 issue of the radical lesbian feminist periodical Sinister Wisdom titled “The Tribe of Dina.” In the editors’ notes, Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz and Irena Klepfisz write that “Dina” has a dual purpose: first, to create “coalitions among Jews…and to connect Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jews, observant and secular, gay and heterosexual, on issues of concern to some or all of us;” and second, to fight antisemitism as it intersects with sexism, racism, xenophobia, and classism to oppress Jewish women and all women. I read the book in one sitting, without once getting up from my chair in the library basement.

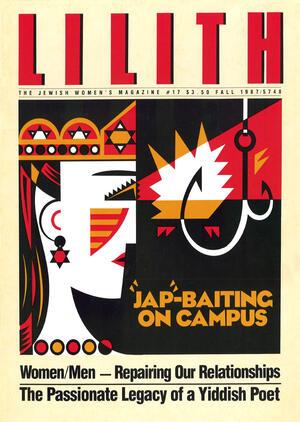

I won’t say that I was immediately radicalized or spurred to action by “The Tribe of Dina.” If anything, I felt intimidated by the goliathan pursuit of justice to which the editors and authors in the work dedicated themselves. Having grown up in the Trump era, I was discouraged that many of the “issues of concern” for Kaye/Kantrowitz and Klepfisz are challenges my generation is still striving to overcome. But later in my research, I found an article in a 1987 issue of Lilith that stayed with me through the rollercoaster of 2020.

In a powerful and uplifting exposé called “Mother Nature and Human Nature: The Poetry of Malka Heifetz Tussman,” Marcia Falk celebrates Tussman as a midcentury Yiddish writer, activist, mother, and mentor. Tussman, a Ukranian immigrant, wrote stories and poems in Russian, Hebrew, English, and Yiddish. The two women met at a Jewish arts festival in Berkeley, California, and afterwards Falk began to translate Tussman’s poetry into English. They became friends and exchanged poetry, letters, and recipes.

Laid out at the beginning of the article, Tussman’s poem “I AM WOMAN” claims Jewish womanhood in a series of statements that begin with “I am” and emphasize Jewish women’s multifaceted natures. In the first part of the poem, each verse characterizes the sacrifices Jewish women made throughout history to enable their communities’ and families’ survival. At a turning point in the poem, the speaker declares herself an able rebel, a “barrier-breaker / who distributed Bread and Freedom / and freed love from the wedding canopy.” “Bread and Freedom” is a reference to Tussman’s work in Chicago’s anarchist-socialist political scene of the 1920s, where she advocated for economic justice and Marxism at the risk of deportation and arrest. This woman seems very different from the “obedient bride” who was exalted earlier in the poem, and yet she is given equal weight, attention, and praise. Throughout the poem, Tussman creates a developmental arc that begins within patriarchal norms and ends outside of such norms. The woman described in Tussman’s poem is one who works for justice as outlined in “The Tribe of Dina,” and I was encouraged to see complexity and vulnerability in Tussman’s narrator.

Tussman concludes by writing “I am all these and many more. / And everywhere, always, I am woman.” “I AM WOMAN” fiercely reminds its audience that Jewish women are anything and everything they wish to be: powerful, spiritual, sexual, intellectual, and faithful. Falk ends her article with a copy of a letter sent to her by Tussman in 1975, near the end of her life. Tussman notes the purpose of her writing, exemplifying the spirit of community so often conjured by poetry of the second wave: “And so my poetry is still travelling the endless road of ‘the Self’ to reach ‘the You.’ It knows no other road… Love, Malka.” This correspondence and the poem reinforced the importance of the message of “Dina.” Tussman, and this letter to Falk, embody the fullness of Jewish feminism that seeks to bridge generations, reclaim and redefine Judaism for women, and elevate anyone, anywhere, who is struggling. .

Throughout the turmoil of 2020, Tussman’s work and the “Dina” collection remains some of the only media that have both kept me grounded and challenged my sense of self and community. I see a declaration of purpose throughout these writings. Feminist Judaism invokes a higher calling in service of marginalized people and those in need, a call that has echoed loud and clear through every social media post and news article relevant to the pandemic, to Black Lives Matter, or to voter suppresion. While I have felt lost and unmoored when confronting the tragedies that permeated the American public consciousness in 2020, Falk’s article has shown me two important things. First, I am not alone. Even in the most isolating and scary moments, I can return to the community created within Jewish feminist literature from my COVID-safe bubble. Second, even when it feels like no progress is possible, Tussman’s powerful affirmation of Jewish womanhood reminds me that I have the strength to take up the mission for empowerment outlined in “The Tribe of Dinah.”

I started my project on Jewish feminist poetry when I was wrangling with self-definition and independence as a first semester college student. Returning to these writings has motivated me, grounded me, and guided me through the challenges of the past year—and I know I will continue to access Jewish feminist texts for wisdom and fortitude when I need them.

A powerful, inspiring article. I will be reading I AM WOMAN soon.