How “TimTum: A Trans Jew Zine” Taught Me to Be a Sexy, Smart, Creative, Productive Jewish Genderqueer

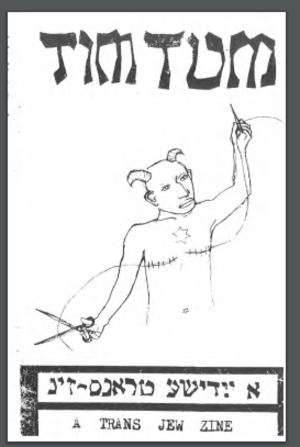

Cover of Micah Bazant's zine "TimTum: A Trans Jew Zine."

I discovered Micah Bazant’s “TimTum: A Trans Jew Zine” in early high school, at a critical juncture (read: identity crisis) in my new understandings of myself as a Jew, a gender-questioning person, a queer person, a woman, and a feminist. I was beginning my social transition after years of intense questioning and mental health issues. I was also starting to explore my Jewish identity again, which I had for so long suppressed out of shame and fear.

When I first started to question my gender and socialization, Judaism felt distant, closed, and unreachable. I believed that Jews couldn’t be queer. To be Jewish, I would have to find my place in a culture of strict law and gender rigidity or face social and spiritual exile from my community. If I was Jewish, then I couldn’t be queer, and if I was queer, I’d have to reject my Jewishness.

I decided that I would be queer, and my Judaism faded into some kind of old relic of my boy-self. I felt empty and identity-less. One of my friends, after unsuccessfully prodding me to go to Jewish Student Union at school, showed me an essay by Rabbi Elliot Kukla, the first openly trans person to be ordained by Hebrew Union College. In this essay, Rabbi Elliot Kukla introduced me to the timtum, which Kukla’s teacher described as a “mythical beast” or a gender unicorn of sorts, designed by the Sages to test the limits of halacha.

“Timtum” is a Yiddish word (from the Hebrew word tumtum) with a meaning as defined and as nebulous as gender itself. It can mean an androgynous person whose gender is ambiguous or even nonexistent, an effeminate man without facial hair and a high-pitched voice, or a misfit. Or, in the words of Micah Bazant, it can mean “a sexy, smart, creative, productive Jewish genderqueer.”

During my research on timtumim I stumbled upon Micah Bazant’s zine. It was surreal to read, and it felt impossible that writing like this could even exist. For the first time, I saw a concrete expression of my gender trouble—and it was so unapologetically Jewish. It articulated what I never could about the often-violent intersections of queer and Jewish identities and histories, the powerful push to assimilate in a Christian cisheteropatriarchal society, and the queerness of Judaism and the Jewishness of queer experience.

The zine is at times dark and disturbing—and also hopeful and beautifully subversive. As I traveled through Bazant’s essays, drawings, letters, emails, prayers, and accounts of queer Jewish history, I found myself following a basic thread: to be Jewish and to be queer is to survive, and to survive is to rebel.

While I used to see my queerness and Jewishness as fundamentally incompatible, through this zine I felt empowered to consider how these identities informed and enriched each other, and also function as remarkably similar realities (while by no means existing as homogenous categories). Both share that isolation, repression, beauty, and disruption of societal pigeonholing.

According to Bazant, being Jewish is about a common narrative of exile, of “being in a place, but not fully being there—a sense of displacement, millennia of wandering, of watching your back.” I felt, and feel, so much comfort in the Jewish precedents for my internal battle as a trans/queer person between “pride” and “passing” (as if they are mutually exclusive), for feeling in a state of constant exile while also rooted to the past. The zine doesn’t confine Judaism or queerness to labels defined only by oppression and suffering, but also by their manifestations in joy and creativity. To me, Bazant is not saying that to be Jewish is to survive, and survival is good, but rather that to be Jewish is to survive, and survival is nourishing and queer and revolutionary. Bazant says that “we [Jews] didn’t survive in spite of [our tradition], but because of it.” They offer that Judaism and queerness aren’t “un-normal” themselves but are touchstones for resisting structures that dictate normalcy and assimilation in the first place.

While I used to think Judaism was only rooted in trauma, painful memory, and an instinctive urge to survive, I now see Judaism as inventive, whimsical, and unambiguously queer because its existence challenges societal norms and conformity to a specific system of hegemony.

“I feel like Judaism is a secret package delivered to me through time, disguised and concealed, hidden from the enemy, smuggled through hell under layers and layers of protective cover,” Bazant writes. “With parts so dangerous and large that they were sometimes unknown to the smugglers themselves.” Jewishness and queerness are coded legacies of disruption, sometimes passed down and sometimes covered-up, but always transgressive. I understand Judaism and queerness not as surviving despite oppression, but as surviving in order to dismantle oppression.

My transness is not defined by my dysphoria or my gendered otherness; my transness informs me to deconstruct systems of power that keep me and others othered. Jewishness and queerness may not be revolutionary on their own (the politicization of trans identity is another conversation), but they do give us the tools to revolt.

I find myself revisiting “TimTum” again and again—for comfort, and to challenge my conceptions of Jewishness, queerness, gender, and rebellion. I reread “TimTum” on the day of my name-change ceremony at my synagogue. It still makes me cry, gives me strength, and inspires me to destruct, create, rebel, and survive. “TimTum” allows me to say: “I Am Not One Thing. I Am My Own Very Special Thing.” It gives me permission to take up space. It teaches me to resist and to embrace my being as something sexy, smart, creative, productive, Jewish, and queer.

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.

A work of art! Thank you! Blessings to you!

Aloha, Gail

What a brilliant and beautiful essay! I have shared it with friends gay and straight, trans and cis, Jewish and gentile. Thank you, Avivit, for helping me reimagine Judaism as "inventive, whimsical, and unambiguously queer because its existence challenges societal norms and conformity to a specific system of hegemony."

The self awareness of young people coming of age within the Queer Jewish community gives me such naches and hope. I am so deeply moved, thank you for sharing and putting these words into the world!

This piece is incredibly moving and insightful. The weaving of your language and self-empathy makes my heart sing.

In reply to This piece is incredibly… by Jessie

Amen!