Grace Paley

Grace Paley wrote highly acclaimed short stories, poetry, and reflections on contemporary politics and culture. Paley dropped out of college, but a later course she took with W.H. Auden proved transformative: the poet suggested she use the language of her own time and community rather than mimicking other writers. Her stories often reflected on a range of Jewish identity issues of concern to largely assimilated urban American communities, but most often her speakers are women pondering the nature of friendship, love, or family. A rare example of a writer deeply engaged with the world, Paley made an impact as much through her activism as her writing. The combination of neighborhood and increasingly global concerns led her to a prominent role in the peace movement of the 1960s; she also became an outspoken advocate of Palestinian rights.

Career Overview

“‘Men are different than women,’ said Joanna, ‘and it’s the only thing she says in this entire story’” (“A Woman, Young and Old”). Much of Grace Paley’s fiction elaborates this apparently simple observation, calling attention to the act of writing, which complicates all such simplicities.

Paley wrote highly acclaimed short stories, poetry, and reflections on contemporary politics and culture. Her settings are primarily urban, taking her readers to the apartments, playgrounds, and streets of New York. Her characters are usually women who speak in the first person. Often they are Jewish, and always they are concerned with questions of relationship. The protagonists she created are not heroic in the traditional sense of the word, but they manage surprisingly well in a world that is often less than friendly.

Paley’s literary prominence is the result of almost three decades of writing during which she produced three volumes of short stories critics invariably describe as highly crafted. After The Little Disturbances of Man appeared in 1959, she received a Guggenheim Fellowship (1961) and a National Endowment for the Arts Award (1966). Enormous Changes at the Last Minute was published in 1974, followed by Later the Same Day in 1985, the year in which her first collection of poems, Leaning Forward, appeared. In 1980, she was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters. In 1986, she was awarded a PEN/Faulkner Prize for fiction and also named the first State Author of New York. In 1987, she received a National Endowment for the Arts Senior Fellowship. In addition to Paley’s New and Collected Poems (1992), she and her friend Vera B. Williams produced two volumes of stories, poems, essays on contemporary life, and illustrations: 365 Reasons Not to Have Another War was first published as a date book by the War Resisters League and New Society Publishers (1988) and reissued with additions by the Feminist Press as Long Walks and Intimate Talks (1991).

Family and Education

The youngest of three children, Grace Goodside Paley was born into a comfortably middle-class family living in the Bronx. Her parents were Ukrainian socialists who came to the United States in 1906, after both had been arrested for participating in workers’ demonstrations and one year after her father’s brother had been killed by the czarist police. (Paley memorialized this event in her story “In This Country, but in Another Language, My Aunt Refuses to Marry the Men Everyone Wants Her To.”) Within a few months, the couple’s first child, Victor, was born, followed two years later by a daughter, Jeanne. Grace was born fourteen years later, on December 11, 1922. By then, her working-class father had gone to medical school and established a successful practice. His mother and two sisters had followed the young couple to America and lived with them. The family’s native Russian was augmented by the Yiddish spoken by the elder Mrs. Goodside and on the Bronx streets, where English vied for prominence with other languages. The cadences of Russian and Yiddish speech continued to resonate in Paley’s fiction.

Following an undistinguished period of study in high school and college, Paley dropped out of school and held various office jobs, occasionally taking courses as well. A class she took with W.H. Auden at the New School for Social Research was to prove especially significant. Auden read his young student’s poetry and advised her to echo the spoken language in which she lived rather than the language of some literary ideal about which she may have read. She took his advice both in the poetry she continued to write and the short stories she began writing more than a decade later.

In 1942, Grace married Jess Paley. They had two children (Nora, born in 1949, and Danny, born in 1951). The couple separated in the late 1960s and divorced in 1972, the year in which she married Bob Nichols, a family friend and political ally. She taught briefly at a number of New York universities (Columbia, NYU, Syracuse, and City) and for twenty-two years (1966–1988) at Sarah Lawrence, whose Bronxville campus is geographically near but socially remote from the Bronx neighborhood of her childhood.

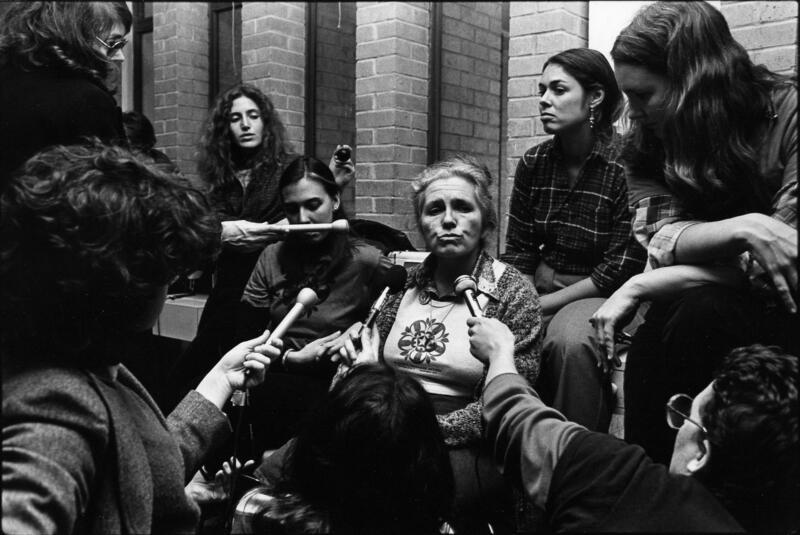

Political Activism

Recognized as an accomplished writer of short fiction, Paley was equally renowned as a political activist, a role that began, as it might have for many of the characters she created, as an extension of PTA activities in her children’s school. The combination of neighborhood and, increasingly, global concerns led her to a prominent role in the peace movement of the 1960s and a series of often controversial trips to some of the world’s most troubled nations, among them North Vietnam in 1969, Chile in 1972, the Soviet Union in 1973, Nicaragua and El Salvador in 1985, and Israel in 1987.

Paley was one of the founders in 1987 of the Jewish Women’s Committee to End the Occupation of the West Bank and Gaza and was an outspoken advocate of Palestinian rights. That activity is significant as an indication of her engagement in women’s issues, as well as her concern with Israel. In her fiction, she created characters who speak eloquently on behalf of the diaspora. One of the most explicit and often-cited examples of such views can be found in “The Used-Boy Raisers,” written in the 1950s, when Israel was barely a decade old. In this story, Faith, the central character of a cycle of short stories that span Paley’s writing career, reflects on her relationship to her two husbands and to Jewish concerns. Denying any knowledge of the significance of the Lit. (Aramaic) "holy." Doxology, mostly in Aramaic, recited at the close of sections of the prayer service. The mourner's Kaddish is recited at prescribed times by one who has lost an immediate family member. The prayer traditionally requires the presence of ten adult males.Kaddish (mourner’s prayer), Faith rejects Israel “on technical grounds” as well. “I believe in the Diaspora,” she tells her former and present husbands, insisting that once Jews are “huddled in one little corner of a desert, they’re like anyone else.... Jews have one hope only—to remain a remnant in the basement of world affairs ... a splinter in the toe of civilizations, a victim to aggravate the conscience,” a function Paley herself certainly served in her political life.

Writing About Jewish and Female Identity

Paley’s stories often reflect on a range of Jewish identity issues of concern to contemporary, largely assimilated urban American communities. She did not create characters who are religiously observant, or Zionists, or committed to particularly Jewish causes. No matter what their age, marital status, or work, her Jewish characters are liberal, modern figures. Those who are immigrants speak a Yiddish-inflected English. Their offspring speak in less foreign tones but share the political and social commitments of the elders with whom they may nonetheless argue. In “Zagrowsky Tells,” for example, readers once again meet Faith, this time confronting the old pharmacist Zagrowsky and the black child whom Faith cannot believe is his grandson. Faith reminds Zagrowsky that in the past he was considered a racist and sexist, asserting that the only reason his attitudes were tolerated was that “it wasn’t time yet in history to holler.” His rejoinder is to note parenthetically “(an American-born girl has some nerve to mention history).” In such invocations of the Eastern European Jewish past, readers encounter a characteristic of Paley’s writing that may be thought of as oblique confrontation. Differences between opposing figures—men and women, parents and children, young and old, police and demonstrators—are not minimized in Paley’s stories. Rather, conflicts are resolved or left suspended among pithy, trenchant verbal exchanges that activate a psychic or physical world the interlocutor may not have considered.

Most often, Paley’s speakers are women pondering the nature of friendship, love, or family. The stories in which we find them frequently parody traditional romantic tales, as the subtitle of her first volume would indicate. When The Little Disturbances of Man appeared in 1959, it carried the subtitle “Stories of Women and Men at Love,” calling attention to the deliberate skewing of established tropes. (When it was reissued, that bold title was tamed, rendered into the less oppositional “Stories of Men and Women in Love.”) Paley’s protagonists speak in equally irreverent, earthy tones about social and sexual intercourse, “that noisy disturbance,” as the latter is called in “Enormous Changes at the Last Minute.” At the same time, such women also take enormous pleasure in love. Despite their abandonment by men, their struggles to raise children alone in a community of other mothers, or the presence of men who are able to father children but not to raise them, these women revel in the life of the body. Only on the last page of her last volume of stories did Paley include a character whose physical life has nothing to do with men. In “Listening,” Cassie complains that Faith is willing to tell “everyone’s story but mine.” Rather than the insistent focus on women and men, she asks, “Where the hell is my woman and woman, woman-loving life in all this? ... Why have you left me out of everybody’s life?” It is an accusation that Faith, often a stand-in for the writer herself, immediately accepts as just. To be left out of the story, silenced or unheard, is a wrong individuals must counter as if their very lives depended on it.

The Importance of Speech

Although questions about both Jewish and female identity are significant in Paley’s stories, they yield to the unmistakable precedence she gives to speech. Central to the structure and themes of every text Paley wrote is talk: the words of anger, uncertainty or, more commonly, love and acceptance that characters utter to one another, to themselves, and to the reader.

The ability to reconcile the sounds of Yiddish, Russian, and English, along with the signs of Jewish and Christian culture, depends on the ability to speak up loudly and clearly. Nowhere is this more pronounced than in “The Loudest Voice,” a short story in her first collection of stories. In their commonsense approach to the world around them, as in their use of irony and clever banter, Paley’s characters give new, quite literal significance to the idea of living by one’s wits.

Telling stories is, then, an enterprise that matters tremendously in Paley’s stories, which contain frequent allusions to the craft of writing. The autobiographical narrator of “A Conversation with My Father” wants to please her father, who wishes she would write “a simple story ... just recognizable people and then write down what happened to them next.” But she cannot write a story driven by plot, “the absolute line between two points,” because such a construction “takes all hope away. Everyone, real or invented, deserves the open destiny of life.” It is certainly not simplicity or comprehensibility that Paley disavows, but rather the determinism of conclusive, linear stories. As another autobiographical narrator in “Debts” explains, uttering what may serve as Grace Paley’s literary manifesto, the storyteller’s obligation to family and friends is “to tell their stories as simply as possible, in order, you might say, to save a few lives.”

Grace Paley died on August 27, 2007.

Selected Works

A Grace Paley Reader: Stories, Essays, and Poetry. New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux, 2017.

Fidelity. New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux, 2008 (posthumously).

Begin Again: Collected Poems. New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux, 2000.

Just As I Thought. New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux, 1998.

The Collected Stories. New York: Macmillan, 1994.

New and Collected Poems. Thomaston, ME: Tilbury House, 1992.

Long Walks and Intimate Talks. New York: The Feminist Press, 1991.

Later the Same Day. New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux,1985.

365 Reasons Not to Have Another War. New York: War Resisters League, 1988.

Leaning Forward: Poems Granite Press,1985.

Enormous Changes at the Last Minute. New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux, 1974.

The Little Disturbances of Man. New York: Doubleday, 1959.

Aarons, Victoria. “A Perfect Marginality: Public and Private Telling in the Stories of Grace Paley.” Studies in Short Fiction 27, no. 1 (Winter 1990): 35–43.

Arcana, Judith. Grace Paley’s Life Stories: A Literary Biography. Champaign-Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993.

Baba, Minako. “Faith Darwin as Writer-Heroine: A Study of Grace Paley’s Short Stories.” Studies in American Jewish Literature 7, no. 1 (Spring 1988): 40–54.

Hirsch, Marianne, “What We Need Right Now is to Imagine the Real”: Grace Paley Writing Against War, PMLA, January 2009.

Kamel, Rose. “To Aggravate the Conscience: Grace Paley’s Loud Voice.” Journal of Ethnic Studies 11 (1989): 305–319.

Lyons, Bonnie. “Grace Paley’s Jewish Miniatures.” Studies in American Jewish Literature 8, no. 1 (Spring 1989): 26–33.

Oates, Joyce Carol. “The Miniaturist Art of Grace Paley.” London Review of Books, April 16, 1998.

Satz, Martha. “Looking at Disparities: An Interview with Grace Paley.” Southwest Review 72 (Autumn 1987): 478–489.

Taylor, Jacqueline. Grace Paley: Illuminating the Dark Lives. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1990.