Women's Studies in the United States

Jewish women were instrumental in creating women’s studies as an academic discipline and contributed significantly to its growth and evolution. The first phase of the field of women’s studies was profoundly affected by scholars who had their political roots in the women’s movement. By the mid-1970s, feminist thinking adopted a woman-centered focus that located specific virtues in the historical and psychological experiences of women. Debates in the late 1980s anticipated the third phase of women’s studies scholarship, in which several interrelated issues became paramount: woman as a universal category, multiculturalism, and how to link feminism to other sociopolitical approaches and poststructuralist criticism. Jewish women’s prominence within the field of women’s studies may be due to their experiences of marginalization, both as women and as women within the Jewish tradition.

Introduction

What we have at present is a man-centered university, a breeding ground not of humanism, but of masculine privilege.

Adrienne Rich, On Lies, Secrets, and Silences

Women’s studies has been variously referred to as a “process,” a “field of inquiry,” a “critical perspective”, and/or “the academic arm of the Women’s Movement” (Coyar, 1991). Although women’s studies grew out of the women’s movement, faculty and students recognized that women’s poor representation in the professional and political sphere was in part a reflection of and produced by the invisibility of women’s experiences in the curricula, research priorities, and methodologies in higher education (Jaschik, 2009; National Women’s Studies Association, 1990). Early formulations posited that, as an academic discipline informed by feminist activism, women’s studies was specifically “by, for, and about” women. That has changed.

The first wave of feminism began with the 1848 Women’s Rights Conference at Seneca Falls and is typically understood to have ended with the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, when women’s right to vote was ratified. Not until the 1960s did second wave feminism emerge and with it a new academic discipline, Women’s Studies. Hester Eisenstein (1983) characterizes Women’s Studies as having several overlapping phases of intellectual inquiry, each of which influenced the debates considered central to the development of the discipline. The first phase focuses on equal rights and gender differences, the second approaches gender differences from a woman-centered perspective, and the third revolves around woman as a universal category, multiculturalism, intersectionality, and how to link feminism to other existing or emerging socio-political and poststructuralist criticisms. Although these phases of women’s studies scholarship overlap in significant ways and are not mutually exclusive, they do provide a way of categorizing different intellectual concerns across a changing field of inquiry, one that has moved in name and content among many universities and colleges from women’s studies to women’s, gender, and sexuality studies. Moreover, the third phase, as Eisenstein names it, is considered by some to be better labeled the beginning of third-wave feminism.

Jewish women have contributed significantly to the academic arm of women’s studies from its inception. Their significant contribution may be due to their experiences as the “other” in both secular society and in the world of Jewish patriarchy. They have been crucial not only as researchers, writers, scholars, teachers, political activists, administrators, and editors of some of the key women’s studies journals, but also as prominent thinkers in the intellectual debates within their respective disciplines. As heads of and participants in women’s studies programs, they help shape the angle of vision for scholarship, maintain the programs’ credibility on campuses through curricula and research development, and support and recruit other scholars. Their efforts represent an immeasurable and often undervalued task of keeping women’s studies and its many scholarly offshoots vibrant.

Phase One

In her intellectual history of feminist thought, Hester Eisenstein (1983) outlined the chief argument of the first phase of women’s studies scholarship: that the socially constructed differences in power and opportunity between the sexes are the chief source of female oppression. In this phase, discussions emphasized the distinctions between sex and gender (biology and the social construction of sex roles, later to be referred to as gender roles) and how to minimize differences between men and women. This first phase of women’s studies scholarship included women who had their political roots in the women’s movement and whose arguments set the stage for some of the key debates in the field and for feminist theory. Shulamith Firestone’s The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution (1971), Susan Brownmiller’s Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape (1975), and Andrea Dworkin’s Our Blood: Prophecies and Discourses on Sexual Politics (1976) were central to women’s studies scholarship and feminist theory in that they addressed the relationship among and between reproductive roles, sexual violence, and the physical and psychological oppression of women. Each put forth a radical, historical critique of reproduction and sexual violence that highlighted the extent to which reproduction and sexual violence are a result of masculine social power, not female biology.

Many of the women responsible for editing the first feminist academic journals and airing some of the major debates were not only tied closely to the feminist movement and the New Left but were also central in defining the discipline and the content of women’s studies within the university. Frontiers, Feminist Studies, and SIGNS were among the three earliest academic journals that covered interdisciplinary feminist scholarship and research. Perhaps because it initially drew on women from a consciousness-raising group organized around Columbia University’s women’s liberation group, a women’s studies lecture series at Sarah Lawrence College, and community activists in New York City (where Jews are demographically overrepresented), Feminist Studies since its inception has had a clear presence of Jewish editors, contributing editors, and consultants. Its association with the prestigious Berkshire Conference on the History of Women made it, in its time, the leading publication of social history and materialist feminist analysis. Therefore, it is not surprising that its editorial staff was primarily made up of historians and historical sociologists with roots in the New Left.

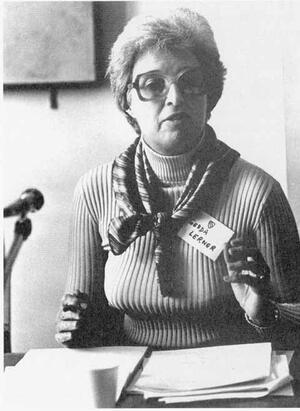

The politically informed scholarship of Marxist-oriented social historians and sociologists in the pages of Feminist Studies was best formulated by such scholars as Nancy Cott, Linda Gordon, Alice Kessler-Harris, Gerda Lerner, Sherry Ortner, Rosalind Petchesky, Elaine Showalter, Kathryn Kish Sklar, and Judith Stacey. All later published their work with mainstream scholarly presses and became leading women’s studies scholars in their respective fields. They focused on such issues as the division of labor into public and private spheres, the family as a unit of production, housework and mothering as unpaid labor, and society’s control of female sexuality and reproduction. Even those who were not historians emphasized how women’s experiences and oppression were shaped by their relations to historically specific contexts.

Gerda Lerner’s earliest works were critical to the development of some of the first women’s studies courses in the country: “The Lady and the Mill Girl” (1969) was an early example of class analysis in women’s history; her documentary anthology Black Women in White America (1972) demonstrated the importance of African American women in women’s history; and in The Female Experience (1976), she reorganized history around life-cycle stages. Lerner was the Robinson Edwards Professor Emerita at the University of Wisconsin (until her death in 2013). One among many of her lasting legacies was her founding of the PhD program in Women’s History at the University (earlier she had established the first graduate program in Women’s History at Sarah Lawrence).

Katherine Kish-Sklar, Distinguished Professor Emerita at the State University of N.Y., Binghamton, 1996 winner of the Berkshire Book prize for the best book written by a woman historian in North America in any field (Florence Kelley and the Nation's Work: The Rise of Women's Political Culture, 1830-1900 (1995)), and earlier the recipient of the Berkshire prize for her book Catharine Beecher: a Study in American Domesticity (1974), helped to create the field of women’s history by co-directing (with Gerda Lerner) an NEH-sponsored conference on graduate training in U.S. Women’s History.

Alice Kessler-Harris, co-author with Katharine Kish-Sklar and Linda Kerber of U.S. History as Women’s History: New Feminist Essays (1995) and R. Gordon Hoxie Professor Emerita of American History at Columbia University, has earned wide acclaim for bringing working-class women into historical focus with her classic book, Out to Work (1982). Nancy F. Cott, one of the first historians in the early 1970s to specialize in women’s history, is the Jonathan Trumbull Professor of American History at Harvard University. Some of her groundbreaking books concerning women, gender, marriage, feminism, and citizenship from the eighteenth century to the contemporary United States include the pathbreaking anthology Root of Bitterness: Documents of the Social History of American Women (1972), The Bonds of Womanhood: “Woman's Sphere” in New England, 1780–1835 (1977), and The Grounding of Modern Feminism (1987).

Professor Emerita in the History Department at Yale University, Linda Gordon’s early work, Woman's Body, Woman's Right: A Social History of Birth Control in America (1976; 1977; revised 2nd edition, 1990) and Heroes of Their Own Lives: The Politics and History of Family Violence (1988; 1989; winner of numerous awards and prizes including American Historical Association's Joan Kelly Prize for the best book in women's history or theory), give testimony to her place in the field of women’s history. Rosalind Pollack Petchesky, an American political scientist and Distinguished Professor of Political Science at Hunter College, City University of New York, recipient of a 1995 MacArthur Fellow award, founder of the International Reproductive Rights Research Action Group (IRRAG), and former Coordinator of Women's Studies, is known for her historically informed work in the field of women’s studies. Her influential article "Abortion and Woman's Choice: The State, Sexuality, and Reproductive Freedom" (1990) is a significant example of such early interdisciplinary contributions to history and women’s reproductive rights.

As activist, educator, scholar, and publisher of the Feminist Press, Florence Howe played a critical part in legitimating women’s studies scholarship by establishing a place for the publication of women’s studies monographs. Similarly, Barbara Haber (1981) brought together the scholarly work of many first phase feminists by editing The Woman’s Annual: 1980 Year in Review and Women in America: A Guide to Books, 1963–1975, with an Appendix on books published between 1976 and 1979. In 1981, Annette Kolodny won the Modern Language Association’s Florence Howe Award for her article arguing that academic journals should stay responsible to the community of feminists outside the academy as well as those within. Kolodny, who was among the leading feminists in the field of American literary theory and criticism wrote, "Dancing Through the Minefield: Some Observations on the Theory, Practice, and Politics of a Feminist Literary Criticism" (1988), a widely disseminated essay (translated and reprinted worldwide).

Frontiers, founded in 1975, had as its mission to heal the breach between feminists in the university and those in the community. Its focus on community and regional interests led to two very important special issues on women’s oral history. In 1977, the first of these volumes was published under special guest editor Sherna Gluck (Director of Oral History Program, California State University). Its success prompted “Women’s Oral History Two” in 1983, with a contribution by Sydney Stahl Weinberg, Professor of History at Ramapo College (died 2021), about the world of Jewish immigrant women (1983; 1988). Frontiers consistently underscored the diversity of female experience, especially from the lesbian perspective, and in 1979, guest editor Judith Schwarz did a special issue on lesbian history. The overlap between and among these second-wave feminists created a network of powerful academic women who advanced women’s history in both the curriculum and in historical scholarship.

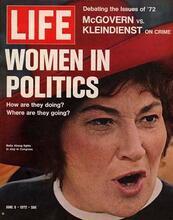

Liberal feminism of this period, first voiced and best expressed in Betty Friedan’s landmark The Feminine Mystique (1963), stressed the similarity between the sexes and the lack of equal opportunity to explain women’s poorer achievements than men in the public spheres of education and the labor market. Some of the major contributions to “liberal feminist” thinking in this first phase came from the social sciences, especially sociology and psychology. The editors, contributing editors, and consultants of such journals as Journal of Sex Roles, Psychology of Women Quarterly, and, later, Gender & Society made important contributions to women’s studies scholarship by providing a critique of their respective disciplines through a gender analysis.

Janet Saltzman Chafetz (1974) was among the first to analyze the effects of early gender-role socialization. Pioneering work by psychologists such as Roz Barnett (1998), Grace Baruch (1985), Sandra Bem (1993), Nancy Datan (1989), Lois Hoffman (1975), Alexandria Kaplan (1980), Jean Lipman-Blumen (1984), Martha Mednick (1989), Sandra Tangri (1972, editor with Martha Mednick), and Rhoda Unger (1975) rooted women’s difference from men in the social psychological attributes and attitudes found in the socio-cultural construction of femininity.

The pioneering work of several sociologists early in this first phase of women’s studies scholarship raised issues about the invisibility of women in research, scholarship, and the creation of theory and methodology. Scholars recognized that traditional definitions of knowledge were derived from, and set by, the experiences of men and a masculinist tradition of inquiry. Pauline Bart (1971) recast research on menopause (and thereby on life-cycle studies for both men and women) by focusing on role loss as more important than biological changes in explaining depression among midlife women. Preceding by more than a decade the “fear of success” as a theory to explain women’s fewer achievements than men in the professional sphere of work, Mirra Komarovsky (1946) wrote of cultural contradictions and women’s roles, suggesting that women often had to “play dumb” to attract males and/or behave in ways consistent with stereotypical female behavior, which worked against achievement in the public sphere.

Cynthia Fuchs Epstein legitimated and made the study of gender pivotal in the sociology of the professions with her formative book, Woman’s Place (1970). Her network analysis of the “old boy” system launched scores of doctoral dissertations. Judith Lorber was the first coordinator of the CUNY Graduate School’s Women’s Studies Certificate Program, one of the first such centers in the country (1988). Her first book, Women Physicians: Careers, Status and Power (1984) was a classic for those interested in the structural barriers for women in the professions. Shulamit Reinharz broke new ground with On Becoming a Social Scientist (1983), which was the basis for her later work, Feminist Methods in Social Research (1992).

In Another Voice: Feminist Perspectives on Social Life and Social Sciences (1975), Marcia Millman and Rosabeth Moss Kanter posed critical questions for sociology from a feminist perspective. The editors argued that sociologists missed large chunks of human behavior by attending primarily to the formal, official action and actors in the organization of social life. Contributors to this trailblazing anthology suggested that knowledge of the social world and social behavior could be expanded if we included the realities and interests of women in our social science theories, paradigms, substantive concerns, and methodologies. In Men, Women and the Corporation (1977), Kanter argued that sociologists had overlooked important support structures that house large cadres of women (secretaries, clerks, wives) in their analyses of organizational behavior. In addition, she noted that a male managerial model works against the upward mobility of female employees.

With the provocative title “She Did it All for Love: A Feminist View of the Sociology of Deviance” (1975), Marcia Millman demonstrated how the focus on dramatic events and incidents that occur in official locations prevented sociologists from understanding the effects of deviance on victims, family members, and other individuals closely involved but with no place in formal procedures. Arlene Kaplan Daniels (1975; 1970 with Rachel Kahn Hut) and Rachel Kahn-Hut (1970; 1982) were not only vocal about the development of gender studies in the field of sociology but also focused on the relationship between the women’s movement and women’s studies scholarship. Debra Renee Kaufman, co-author of Achievement and Women (honorable mention, C. Wright Mills Award, 1982), reanalyzed the sociological and psychological research on achievement from a feminist perspective. This book provided a critique of the theoretical and methodological assumptions that underestimated and undervalued women’s achievements. It also anticipated the next phase of women’s studies scholarship: the importance of feminine values and practices as both critique and corrective to the male-dominated culture of individualism, materialism, and competitive success. Kaufman’s chapter in Fashioning Family Theory (1990) was among the first contributions to family theory from a feminist-interpretive framework.

For feminist political scientists Ethel Klein (1984) and Virginia Sapiro (1984), differences between men and women were firmly located in the organization and institutionalized patterns of social life in both public and private spheres and/or in the assumptions inherent in the theories and methods used to measure those differences. Anthropologist Michelle Zimbalist Rosaldo (1974) anchored differences between the sexes in the sexual division of labor that associated women with “nature” and assigned them to the lesser-valued private sphere of life. In a critical anthology, Toward an Anthropology of Women (1975), Rayna Reiter Rapp marked the importance of the political uses of academic research, reiterating the need for new studies that focus on the biases that have traditionally trivialized and misinterpreted female roles. The contributors to this volume, many of them Jewish women anthropologists, such as Lila Leibowitz (1975) and Ida Susser (1975), addressed Rapp’s cautions. Leibowitz re-examined the popular belief that the physical differences between the sexes are directly responsible for social-role differentiation, concluding that even for monkeys and apes, early socialization is pivotal for future development and survival. In one of the first major urban ethnographies, Susser offered an analysis of women’s grassroots organization on a neighborhood level. All the contributors offered a critical reanalysis of cultural and biological evolution, data on the productive roles of women, and the complexities of patriarchal living.

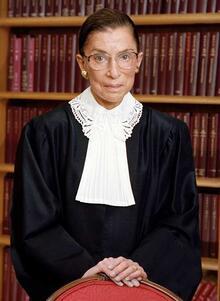

In 1973, the University of Chicago Press published a special issue of the American Journal of Sociology entitled “Changing Women in a Changing Society.” Impressed with the number of copies sold, the press agreed to publish SIGNS: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. From its inception, the editors wanted academic recognition and legitimization for feminist scholarship. The first editor of SIGNS used the Barnard, Columbia, Sarah Lawrence, Rutgers, and New York City network of feminist scholars. The editorial staff reflected the clear presence of Jewish women: Sandra L. Bem, Barbara R. Bergmann, Francine Blau, Joan Burstyn, Nancy Chodorow, Natalie Zemon Davis, Cynthia Fuchs Epstein, Estelle B. Freedman, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Linda Gordon, Carolyn Heilbrun, Lois Wladis Hoffman, Florence Howe, Mirra Komarovsky, Gerda Lerner, Ruth B. Mandel, Ruth Barcan Marcus, Elaine Marks, Ellen Messer-Davidow, Hanna Papanek, Harriet Presser, Estelle R. Ramey, Rayna Rapp, Michelle Zimbalist Rosaldo, Margaret K. Roseheim, Neena B. Schwartz, Elaine Showalter, Myra Strober, Sheila Tobias, Gaye Tuchman, Naomi Weisstein, and Froma Zeitlin.

Natalie Zemon Davis, Professor Emerita and Henry Charles Lea Professor of History and former Director of the Shelby Cullom Davis Center for Historical Studies at Princeton University is widely acclaimed for her early work in the field of women’s history. Her article, “Women’s History in Transition” (1976), is considered one such foundational piece. A nationally and internationally known scholar, Davis discussed the development and state of the research on European women's history by making the argument that women's history has to be developed in relation to gender history; this includes not only women and constructions of femininity, but also men and ideas of masculinity.

Founder of gnyocritics, a feminist concern with the history of themes and ideas of literature by women, Elaine Showalter, Professor Emerita from Princeton University, is among the early historically grounded literary critics of culture and theory. Among her first and most significant contributions was The Female Malady: Women, Madness, and English Culture, 1830–1980 (1985), an historical examination of women and the practice of psychiatry. Her later work: Hystories: Historical Epidemics and Modern Culture (1997), was known for its controversial exploration of the history of mass hysteria. Similarly, Distinguished Professor of Anthropology at UCLA Sherry Ortner demonstrates an historical and interdisciplinary approach in her scholarship on cultural and feminist theory. Eisenstein (1983) viewed the work in this early period as pointing, explicitly or implicitly, to the replacement of gender polarization with some form of androgyny, a point reinforced by literary scholar Carolyn Heilbrun’s (retired from Columbia University in 1992, died in 2003) Toward a Recognition of Androgyny (1973).

Phase Two

By the mid-1970s, the debates considered central to feminist thinking began to shift. Feminist thinking adopted a woman-centered focus that located specific virtues in the historical and psychological experiences of women. Describing this as the beginning of the second phase of feminist thought, Hester Eisenstein (1983) noted that, instead of seeking to minimize the polarization between masculine and feminine, scholarship of the time sought to isolate and define those aspects of female experience that were potential sources of strength and power for women. In contrast to the first phase, where differences between the sexes were seen as obstacles to achievement and a means of keeping women in their devalued and domestic place, this second phase viewed female differences as positive.

Two books helped to usher in this woman-centered focus: Phyllis Chesler’s Women and Madness (1972) and Gerda Lerner’s The Majority Finds Its Past (1979). In it Lerner shows how the field of women’s history had not only added to historical scholarship but had profoundly influenced the methods, theories, and foci of historical inquiry in general. In addition, Adrienne Rich, a lesbian feminist poet and philosopher, transformed feminist thinking with her writings on sexuality and mothering. In Of Woman Born (1976), Rich directed our attention to the difference between institutionalized motherhood and mothering. Unlike some feminists, she saw a woman’s capacity to bear children as a strength rather than an incapacity. In her work on sexuality, she built on Simone de Beauvoir’s premise that women are originally homosexual, then argued that women’s experience, history, culture, and values are distinct from the dominant patriarchal and heterosexual culture (and undervalued within patriarchy).

With the publication of Reproduction of Mothering (1978), Nancy Chodorow became one of the most influential feminist psychoanalytic theorists of sexual difference. Chodorow argued that the mother is the central element in identity formation. Given female parenting, girls develop relational capacities by internalizing the role of caring and by identifying with their mothers. Boys, on the other hand, learn to reject the female aspects of themselves, such as nurturing and empathy, to adopt a masculine gender identity. As a result, Chodorow argued, adult women are better able to empathize with other people’s needs and feelings, while men develop a defensive desire for autonomy based on the abstract model of the absent father. Chodorow revised Freudian theory by focusing on mother relations, not the Oedipus complex, to explain gender differences.

Carol Gilligan’s In a Different Voice (1982) explored moral development theory from a woman-centered perspective and introduced new thinking about the place of care within a moral developmental framework that focuses primarily on abstract concepts of justice. Her work brought into focus the methodological biases and the conceptual weaknesses of moral developmental theories based largely on traditional male interests and formulations.

A spate of books in this period addressed varieties of women’s experiences, including religious ones. Older works were also recovered for use in women’s studies courses: The Jewish Woman in America (1976), by Charlotte Baum, Paula Hyman, and Sonya Michel, and, later, the readings from On Being a Jewish Feminist (1983) edited by Susannah Heschel. Womanspirit Rising (1979), an important feminist reader in religion, included contributions from Jewish writers such as Aviva Cantor, Naomi Goldenberg, Rita Gross, Naomi Janowitz, Judith Plaskow, and Maggie Wenig. Carol Ochs’s Women and Spirituality (1983) became widely used in introductory women’s studies courses.

In the spring of 1980, Feminist Studies published a scholarly debate important to the second phase of the second wave of women’s studies scholarship: “Politics and Culture in Women’s History.” Focusing on the nineteenth-century “female homosocial world,” it raised the controversial question of the origins of feminism. Could feminism develop outside a female world? This symposium marked the beginning of a host of debates about “women’s culture” in academic journals. Some feared that the affirmation of gender differences and the celebration of traditionally feminine qualities, particularly those associated with mothering, might obscure the power differences between the sexes and the fight against male domination.

The shift from the first to the second phase of contemporary feminist thought was highlighted further in the sexuality debates of the 1980s. A major conference at Barnard College in 1982, “The Scholar and the Feminist IX: Toward a Politics of Sexuality,” clarified some of the key splits among feminists on the issue of sexuality. The event featured 40 participants who represented a wide variety of analytic perspectives, including the two polarized critiques that had evolved from the radical insights of sexual politics in the 1960s. One analyzed how patriarchy shapes female sexuality, extending this analysis of male dominance to include rape, degrading images of women in advertising, the myth of the vaginal orgasm, and pornography. The second explored female sexuality when free of patriarchal distortion and looked to alternative expressions of female sexuality and erotica.

Phase Three or the “Third Wave”?

The debates and scholarship produced in the third phase of women’s studies scholarship anticipated what some have called third-wave feminism. Sociologists Debra Renee Kaufman, Professor Emerita and Matthews Distinguished University Professor, Northeastern University (Rachel’s Daughters, 1991; reprinted 1993); Rebecca Klatch, Professor Emerita University of California, San Diego (Women of the New Right, 1987); and Judith Stacy, Professor Emerita, Department of Social and Cultural Analysis, New York University (Brave New Families, 1991; updated 1998) provided some of the first qualitative work and critical insights into late twentieth-century feminism and fundamentalism, emphasizing fluidity and agency even among women within highly patriarchal settings. Although woman as a universal category and multiculturalism were important to this third phase, a challenging issue was how to link feminism to other existing or emerging sociopolitical approaches and poststructuralist criticisms.

New journals, such as differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies and Genders, addressed the need to incorporate analyses from poststructuralism, cultural studies, and critical studies into feminist analysis. differences, co-founded by Naomi Schor [Breaking the Chain (1987); French feminist theorist, literary critic, and Benjamin F. Barge Professor of French at Yale University until her death in 2001) in 1989, offered a critical forum where difference could be explored in texts ranging from the literary and the visual to the political and the social. For Joan Wallach Scott, another differences editor, relationships of power were the basic unit of analysis when discussing gender. Professor Emerita in the School of Social Science in the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton University, Scott is well known for her work on feminist history and gender theory. Her powerful article “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis,” published in 1986 in the American Historical Review, is considered by some as the scholarly piece that introduced the historical profession to gender history. As its principal concern, Genders focused on constructions of gender within the arts and humanities. Literary theorist Rita Felski (1989) observed that feminism is a critique of values as well as an engaged process of revising and refuting male-defined cultural frameworks. Moving away from a thematized focus on women to gender opened the field of women’s studies to investigations of male subjectivities and the construction of male-defined culture. Such debates raised the provocative question of whether women’s subjective position would remain the privileged focus for women’s studies analyses. One of the most challenging feminist thinkers emerging in this period of time, Judith Butler (the Hannah Arendt Chair at The European Graduate School/EGS and the Maxine Elliot Professor in the Department of Comparative Literature and the Program of Critical Theory at the University of California, Berkeley) went beyond disciplinary boundaries and reframed foundational theories both in feminism and philosophy in their now classic book, Gender Trouble (1989). Later they stirred controversy with the publication of her book: Parting Ways: Jewishness and the Critique of Zionism (2012).

Whether it is a third phase of second-wave feminism or third-wave feminism, we do know that the field of women’s studies has grown in size and scope since its inception in the 1960s. In 2006, the Graduate Consortium in Women’s Studies (MIT), among the first such consortiums in the country, changed its name from Women’s Studies to Women’s and Gender Studies to reflect the growing importance of LBGTQ studies and masculinity studies in the field of Women’s Studies. By 2022, most programs in the United States had gone beyond “Women” in name and scholarship (in some cases deleting “Women/Woman” altogether) to include gender, queer, transgender, and/or bisexual (LGBTQ) in their program/departmental titles, reflecting the theoretical and empirical shifts in thinking over the decades.

Over the same period, Jewish Studies programs have also increased in number and scope. It is not surprising then to find a plethora of women professors crossing departmental boundaries with joint appointments and/or affiliations in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and in Jewish Studies. Many of these scholars use newly developing areas of scholarly inquiry to provide provocative critiques of both current and past research in traditionally male-dominated areas of scholarship. Similarly, as named professors and/or distinguished lecturers for the Association for Jewish Studies, directors and/or chairs of departments and programs, or early career named chairs for young scholars in Jewish Studies, many serve as role models and mentors for younger faculty. The commitment to social, economic, political, gender, and sexual equality is implicit in the writing, teaching, activities, and research of each scholar discussed below.

Jewish Studies and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies: Third Phase and Beyond

Jewish Religious Studies from a Gendered and Feminist Lens:

Scholars of religion have long engaged with questions of gender and sexualities, but the reverse has not been necessarily true. Ann Pellegrini, editor of the Sexual Cultures Series at New York University Press and Professor of Performance Studies and Social and Cultural Analysis, has been in the forefront of bringing religion into gender/sexualities analyses. Her books and articles cross several fields (Lesbian and Gay and Jewish Cultural Studies), setting a model for interdisciplinary analyses. She is co-editor of Queer Theory and the Jewish Question (2003) and co-author of Love the Sin: Sexual Regulation and the Limits of Religious Tolerance (2004). Professor Mara Benjamin is an Associate Professor of Religion, member of the Gender Studies Program, and the Irene Kaplan Leiwant Professor and Chair of Jewish Studies at Mount Holyoke College. In her book The Obligated Self: Maternal Subjectivity and Jewish Thought (2018), she explores the ways in which the physical and psychological work of caring for children presents theologically fruitful terrain for feminists by opening a new approach to psychology and theology.

Rebecca T. Alpert, Rabbi, Dean, and Distinguished Lecturer for the Association of Jewish Studies, is a Professor of Religion and an affiliate of the Jewish Studies and Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies programs at Temple University. She is perhaps best known for her book, Like Bread on the Seder Plate: Jewish Lesbians and the Transformation of Tradition (1998), among the earliest contributions to gender/sexuality studies through a Jewish Studies focus. Rachel Kranson, Associate Professor in the Department of Religious Studies and core faculty member of the Jewish Studies Program and the Gender, Sexuality & Women's Studies Program at the University of Pittsburgh, brings a Jewish perspective to women’s reproductive rights in her key essay “From Woman’s Right to Religious Freedom: The Woman’s League for Conservative Judaism and the Politics of Abortion” (2018). Kranson is also co-editor of the popular anthology A Jewish Feminine Mystique? Jewish Women in the Postwar Era (2010).

Former Chair of the Religion Department and Director of Jewish Studies at Smith College, Lois Dubin teaches and investigates a wide range of topics that contribute to religion and feminist politics. In her early work (1999), she not only developed the concept of “Port Jews” to address the commerce, culture, and politics of early modern Jewish mercantile communities and networks but also provided a model for research depicting the importance of Jews, gender, and Judaism to modern states. Susannah Heschel is the Eli M. Black Distinguished Professor of Jewish Studies at Dartmouth College. Her scholarship focuses on Jewish and Protestant thought during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, including the history of biblical scholarship, Jewish scholarship on Islam, and the history of anti-Semitism. Her numerous publications include Abraham Geiger and the Jewish Jesus (1998) winner of the National Jewish Book Award for Jewish-Christian Relations.

Susan Ackerman is the Preston H. Kelsey Professor of Religion and a faculty affiliate of both Women's and Gender Studies and Jewish Studies at Dartmouth College. Crossing three fields of study, she has reached a broad audience, especially in her early biblical critique, Warrior, Dancer, Seductress, Queen: Women in Judges and Biblical Israel (1998). Lynn Davidman, author of Tradition in a Rootless World: Women Turn to Orthodox Judaism (1991), is the Distinguished Professor of Modern Jewish Studies and Professor of Sociology at the University of Kansas. Her book was among the first to contribute to the study of women who return to Judaism, ba’alot teshuvah [see also: Becoming Unorthodox: Stories of Ex-Hasidic Jews (2015)].

History from a Gendered, Feminist, and Jewish Lens:

Women’s studies scholars have increasingly applied a gender/feminist focus to American Jewish history. Susan A. Glenn, Samuel and Althea Stroum Chair in Jewish Studies and Professor of History at the University of Washington, has pushed disciplinary boundaries and opened new areas of investigation, especially in twentieth-century U.S. cultural and intellectual social history. Her emphasis on the foundations and transformations of group identities is represented in her book Daughters of the Shtetl: Life and Labor in the Immigrant Generation (1990). In it she provided an early model of transatlantic history that examined the social, cultural, and political upheavals that led to the mass migration of Eastern European Jews to the United States between 1880 and 1920 and the significance of gender, ethnicity, work, and unionism in the emerging identities of the Eastern European Jewish immigrant women garment workers. Atina Grossmann, Professor of History in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at Cooper Union, contributes to Modern European and German history, Women’s and Gender Studies, and Jewish Studies not only through her award-winning scholarship Reforming Sex: The German Movement for Birth Control and Abortion Reform, 1920-1950 (1995) and Jews, Germans, and Allies: Close Encounters in Occupied Germany (2007), but also as one of the AJS’s distinguished lecturers.

The Social Sciences from a Gendered, Feminist, and Jewish Lens:

Professor of Sociology at Fordham University Orit Avishai opens new perspectives on gender theory and sexual regimes in both Israel and the United States by bringing her feminist perspectives to religious studies with such articles as “What to do with the problem of the flesh? Negotiating Jewish sexual anxieties" (2012) and “Theorizing Gender from Religion Cases: Agency, Feminist Activism, and Masculinity (2016).” Helen K. Kim is an Associate Dean for Faculty Development, former chair of the Sociology Department, and Professor at Whitman College. Focusing on race and American Judaism in the contemporary era, she is co-author of JewAsian: Race, Religion, and Identity for America's Newest Jews (2016). Early among those writing about Asian Jews, her scholarship has reached an audience beyond an academic one through the New York Times, National Public Radio, and Huffington Post.

Susan Starr Sered, Professor of Sociology at Suffolk University and Senior Researcher at Suffolk University's Center for Women's Health and Human Rights, is a prolific author whose work has been in the forefront of a host of issues relating to women and religion. Her book Women as Ritual Experts: The Religious Lives of Elderly Jewish Women in Jerusalem (1996) was one of the first ethnographies to explore the religious beliefs and rituals of a group of elderly Jewish women. By analyzing their rituals, daily experiences, life-stories, and non-verbal gestures, Sered uncovered the strategies these women developed to circumvent the patriarchal institutions under which they live.

Marla Brettschneider, a political philosopher with a joint appointment in Political Science and Women’s Studies at the University of New Hampshire, is also the coordinator of the Queer Studies program at UNH. Her books include The Narrow Bridge: Jewish Views on Multiculturalism (1996) and Jewish Feminism and Intersectionality (2016). She uses queer theory as an analytic tool by grounding her observations in activist groups. In The Family Flamboyant: Race Politics, Queer Families, Jewish Lives (2006), Brettschneider uses critical race politics, feminist insight, class-based analysis, and queer theory to offer a distinct and distinctly Jewish contribution to debates about contemporary families and the larger project of justice politics.

Philosophy and the Arts from a Gendered, Feminist, and Jewish Lens:

Claire Katz is Associate Dean of Faculties, the Murray and Celeste Fasken Chair in Distinguished Teaching, and Professor of Philosophy at Texas A&M University. Her specific interest in French philosophy and French feminist theory are evident in her book Levinas, Judaism, and the Feminine: The Silent Footsteps of Rebecca (2003). Her book An Introduction to Modern Jewish Philosophy not only provides an accessible introduction to some of the primary Jewish philosophers in the modern period but distinguishes itself from other introductions by its attention to the role of gender. Laura Wexler’s positions as Professor of American Studies, Professor of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, Co-Chair of the Women’s Faculty Forum, and member of the Board of Trustees of the Joseph Slifka Center for Jewish Life at Yale, match the range and influence of her scholarly work (Interpretation and the Holocaust, 2004). Her affiliations with the Film Studies Program, the Program in Ethnicity, Race and Migration, and the Public Humanities Program allow her to cross disciplines and methodologies in innovative ways.

Gail Levin is a Distinguished Professor of Art History, American Studies, Women's Studies, and Liberal Studies at Baruch College and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. In her edited volume Theresa Bernstein: A Century of Art (2013) and her article "Beyond the Pale: Jewish identity, radical politics and feminist art in the United States” (2005), Levin brings back the names and accomplishments of women who have been erased, ignored, or considered secondary in historical scholarship. Judith E. Smith, Professor Emerita of American Studies at University of Massachusetts-Boston, has published and spoken widely on American social and cultural history and on ethnicity and race in popular culture (2010). She was among the first to research citizenship and national belonging through the eyes of Jewish women during and into the Cold War years of the 1950s. Lori Harrison-Kahan is an Associate Professor of the Practice in the English Department at Boston College. She specializes in American literature and culture, women’s writing, and comparative race and ethnic studies. A recipient of the American Studies Association’s Gloria E. Anzaldúa Award for Independent Scholars and Contingent Faculty, she is the editor of The Superwoman and Other Writings by Miriam Michelson (2019) and author of The White Negress: Literature, Minstrelsy, and the Black-Jewish Imaginary (2011). Ella Shohat is an Association for Jewish Studies distinguished lecturer and Professor of Cultural Studies in the Culture & Representation track at New York University. Her early books reflect one of the first forays into feminist politics of representation: Talking Visions: Multicultural Feminism in a Transnational Age (2001) and Dangerous Liaisons: Gender, Nation and Postcolonial Perspectives (1997).

Reclaiming the Holocaust from a Gendered and Feminist Lens:

Over the past few decades, several scholars have taken a gender/feminist approach to the study of the Holocaust. In the first book of original scholarship devoted to women in the Holocaust (1998), Lenore Weitzman, Professor Emerita and Clarence J. Robinson Professor of Sociology and Law at George Mason University, showed how questions about gender lead to a richer and more finely nuanced understanding of life prior to and during the Holocaust. By examining women’s unique responses, their incredible resourcefulness, their courage, and their suffering, the book enlarges our awareness of the experiences of all Jews during the Nazi era. Similarly, Debra Renee Kaufman, Professor Emerita and Matthews Distinguished University Professor, founding Director of Women’s Studies, and Director of Jewish Studies at Northeastern University, guest edited one of the first journal volumes dedicated to Women and the Holocaust (1996). In it, she suggested that, as a discipline, sociology had been silent on Holocaust research and on gender issues. In the preface to that volume, Joan Ringelheim, former Professor of Philosophy and Director of Oral History at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, noted that while an emphasis on gender analysis of the Holocaust might seem irrelevant or irreverent, National Socialism as theory and practice showed no more gender neutrality than it did racial neutrality (1996).

Internationally known scholar Judith Gerson holds a joint appointment in the Departments of Sociology and Women’s and Gender Studies at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, and serves as Affiliate Faculty in Jewish Studies. She is the co-editor of Sociology Confronts the Holocaust: Memories and Identities in Jewish Diasporas (2007), one of the first books to directly challenge the dearth of sociological Holocaust research (including gender research on the topic). Diane L. Wolf is a Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Davis. In her book Beyond Anne Frank: Hidden Children and Postwar Families in Holland (2007), she brings a focus on family dynamics to Holocaust research. She has contributed to work on identity, memory, and trauma (2007). Janet Jacobs is a Sociology Professor and Professor of Distinction in Women and Gender Studies at the University of Colorado, Boulder. Her research focuses on ethnic and religious violence, gender, mass trauma, and collective memory. She has greatly expanded Holocaust research by explicitly using a feminist analysis in both her books: Memorializing the Holocaust: Gender, Genocide and Collective Memory (2010), with all photographs taken on site by the author, and The Holocaust Across Generations: Trauma and Its Inheritance Among Descendants of Survivors (2017). Laura S. Levitt is a former Chair and Professor of Religion at Temple University, where she has also served as the Director of the Women’s Studies and the Jewish Studies Programs. She is one of the first to engage in Holocaust and gender research, in American Jewish Loss after the Holocaust (2007) and Jews and Feminism: The Ambivalent Search for Home (1997). She is co-editor of Judaism Since Gender (2014). Her more recent work builds on her prior innovative work in Holocaust Studies to consider the relationship between material objects held in police storage and artifacts housed in Holocaust collections (2003).

In a category of her own:

Perhaps most representative of the kind of interdisciplinary and gendered work contemporary Jewish scholars do is Rachel Havrelock, Associate Professor of Jewish Studies and English at the University of Illinois, Chicago. She is an active columnist and op-ed writer, a playwright (writer and director of the hip-hop play From Tel Aviv to Ramallah, about the daily lives of young people in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict), and television guest/host on the History Channel’s Mysteries of the Bible and Discovery Channel’s series Who Was Jesus? She has brought her feminist/gender perspective to her pioneering work in Biblical Studies and Environmental Humanities. Her work on gender and the Bible began with a co-authored book, Women on the Biblical Road (1996), in which the authors introduced the idea of a female hero pattern based on evidence from the Hebrew Bible. In her article “The Myth of Birthing the Hero” (2007) and her commentaries in The Torah: A Women’s Commentary (2007), she elaborates on female heroism in the Bible. Her recent work on female political leadership in antiquity can be found in The Oxford Handbook of Feminist Biblical Interpretation and The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Bible and Gender Studies, for which she has served as the editor of the Early Judaism section.

The women cited here are just a sample of the women who emerged as noted representatives of Jewish and feminist scholarship in the past few decades. The meaning and the use of the term feminist and the question of what constitutes feminist scholarship provide the basis for an ongoing discussion about the range of theories and methods that belong to women’s studies. Jewish women within secular institutions have contributed significantly to the making and remaking of feminist/Gender Studies both within and outside of Jewish Studies.

This is an updated revision of my original 1996 essay with the significant help of Sara Sharpe (PhD candidate, University of Toronto, Canada).

Ackerman, Susan. Warrior, Dancer, Seductress, Queen: Women in Judges and Biblical Israel. New York: Doubleday, 1998.

Alpert, Rebecca. Like bread on the Seder plate: Jewish lesbians and the transformation of tradition. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997.

Antler, Joyce, The Journey Home: Jewish Women and the American Century. New York: Free Press, 1977.

Avishai, Orit. "What to do with the problem of the flesh? Negotiating Orthodox Jewish sexual anxieties." Fieldwork in Religion vol. 7, no. 2 (2012): 148-162.

Avishai, Orit. “Theorizing Gender from Religion Cases: Agency, Feminist Activism, and Masculinity.” Sociology of Religion, vol. 77, no. 3 (Fall 2016): 261–279.

Barnett, Rosalind C. "Toward a review and reconceptualization of the work/family literature." Genetic Social and General Psychology Monographs vol. 124 (1998): 125-184.

Barnett, Rosalind C., and Grace K. Baruch. "Women's involvement in multiple roles and psychological distress." Journal of personality and social psychology vol. 49 (1985): 135.

Bart, Pauline. “Middle Aged Women and Depression.” In Women in Sexist Society, edited by Vivian Gornick and Barbara Moran. New York: New American Library, 1971.

Baruch, Grace. "Women's involvement in multiple roles and psychological distress." Journal of personality and social psychology vol. 49 (1985): 135.

Baum, Charlotte, Paula Hyman, and Sonya Michel. The Jewish Woman in America. New York: Dial Press, 1976.

Bem, Sandra L. The lenses of gender: Transforming the debate on sexual inequality. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993.

Benjamin, Mara H. The Obligated Self: Maternal Subjectivity and Jewish Thought. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2018.

Breines, Wini. Young, White and Miserable: Growing Up Female in the 1950s. Boston: Beacon Press, 1992.

Brettschneider, Marla. The Family Flamboyant: Race Politics, Queer Families, Jewish Lives. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2006.

Brettschneider, Marla. Jewish feminism and intersectionality. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2016.

Brettschneider, Marla. The Narrow Bridge: Jewish Views on Multiculturalism. Forward by Cornel West. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1996.

Broverman, I., et al. “Sex Role Stereotypes: A Current Appraisal.” Journal of Social Issues (1972): 59–78.

Brownmiller, Susan. Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape. London: Penguin, 1975.

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Submersion of Identity. New York: Routledge, 1989.

Butler Judith. Parting Ways: Jewishness and the Critique of Zionism. New York: Columbia University Press, 2013.

Chafetz, Janet Saltzman. Masculine, Feminine or Human? An Overview of the Sociology of Gender. Itasca, IL: Peacock, 1978.

Chesler, Phyllis. Women and Madness. New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 1997.

Chodorow, Nancy. Reproduction of Mothering: Psychoanalysis and the Sociology of Gender. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1999.

Cott, Nancy F. Root of Bitterness: Documents of the Social History of American Women. Northeastern University Press, 1972.

Cott, Nancy F. Bonds of Womanhood. Yale University Press, 1977.

Cott, Nancy F. The Grounding of Modern Feminism. Yale University Press, 1987.

Coyar, Sandra. “Feminist Bywords.” In NWSA Journal, vol. 5, no. 3, Autumn, (1991: 349-354).

Datan, Nancy. "Illness and imagery: Feminist cognition, socialization, and gender identity." In Gender and thought: Psychological perspectives. Springer, 1989: 175-187.

Daniels, Arlene Kaplan. “Feminist Perspectives in Sociological Research.” Sociological Inquiry, vol. 45, no. 2‐3 (1975): 340-382.

Davidman, Lynn. Tradition in a Rootless World: Women Turn to Orthodox Judaism. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1991.

Davidman, Lynn. Becoming Unorthodox: Stories of Ex-Hasidic Jews. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Dinnerstein, Dorothy. The Mermaid and the Minotaur. New York: Harper & Row, 1976.

Dubin, Lois C. The Port Jews of Habsburg Trieste: Absolutist Politics and Enlightenment Culture. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999. (Published in Italian in 2010 as Ebrei di porto nella Trieste asburgica: Politica assolutista e cultura dell’Illuminismo.)

Dworkin, Andrea. Our Blood: Prophecies and Discourses on Sexual Politics. New York: Harper & Row, 1976.

Eisenstein, Hester. Contemporary Feminist Thought. Boston: G.K. Hall, 1983.

Eisenstein, Hester, and Alice Jardine, eds. The Future of Difference. Boston: Hall, 1980.

Epstein, Cynthia Fuchs. Woman’s Place. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1970.

Felski, Rita. Beyond Feminist Aesthetics: Feminist Literature and Social Change. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989.

Firestone, Shulamith. The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution. New York: Bantam Books, 1971.

Friedan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique. New York: W.W. Norton, 1963.

“Graduate School Programs in Women’s Studies.” Gradschools.com. http://www.gradschools.com/programs/ womens_studies.html.

Gerson, Judith, et al, eds. Jewish Masculinities: German Jews, Gender, and History. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2012.

Gerson, Judith M, and Diane L. Wolf, eds. Sociology Confronts the Holocaust: Memories and Identities in Jewish Diasporas. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007.

Gordon, Linda. Woman's Body, Woman's Right: Birth Control in America. Viking Adult, 1st edition 1976.

Gordon, Linda. Heroes of their Own Lives: the politics and history of family Violence. Penguin Books, 1988.

Gilligan, Carol. In a Different Voice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982.

Ginsburg, Faye. Contested Lives. Berkeley, CA; University of California Press, 1990.

Glenn, Susan A. Daughters of the Shtetl: Life and Labor in the Immigrant Generation. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1990.

Grossmann, Atina. Jews, Germans, and Allies: close encounters in occupied Germany. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007.

Grossmann, Atina. Reforming sex: the German movement for birth control and abortion reform, 1920-1950. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Haber, Barbara. The Woman’s Annual: 1980 Year in Review. Boston: G.K. Hall, 1981.

Haber, Barbara. Women in America: A Guide to Books, 1963–1975, with an Appendix on Books Published 1976–1979. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1981.

Havrelock, Rachel. "The myth of birthing the hero: heroic barrenness in the Hebrew Bible." Biblical Interpretation 16 (2008): 154-178.

Havrelock, Rachel S. and Mishaʾel Kaspi. Women on the Biblical road: Ruth, Naomi and the female journey. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1996.

Harrison-Kahan, Lori, Miriam Michelson, and Joan Michelson, eds. The Superwoman and Other Writings by Miriam Michelson. Detroit, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2019.

Harrison-Kahan, Lori. The White Negress: Literature, Minstrelsy, and the Black-Jewish Imaginary. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2011.

Heilbrun, Carolyn. Toward a Recognition of Androgyny. London: Victor Gollancz, 1973.

Heschel, Susannah, ed. On Being a Jewish Feminist. New York: Schocken Books, 1983.

Hoffman, Lois Wladis, et. al., eds. Working mothers: An evaluative review of the consequences for wife, husband, and child. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1974.

Jacobs, Janet L. Memorializing the Holocaust: Gender, Genocide, and Collective Memory. London: I.B. Tauris, 2010.

Jacobs, Janet. The Holocaust across Generations: Trauma and Its Inheritance Among Descendants of Survivors. New York: New York University Press, 2017.

Jaschik, Scott. “'The Evolution of American Women's Studies.'” Inside Higher Ed, March 27, 2009. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2009/03/27/evolution-american-women….

Kahn-Hut, Rachel, et.al., eds. Women and work: Problems and perspectives. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

Kaplan, Alexandra G., and Mary Anne Sedney. Psychology and sex roles: An androgynous perspective. Boston: Little, Brown, 1980.

Katz, Claire Elise. An introduction to modern Jewish philosophy. London: I.B. Tauris, 2013.

Katz, Claire Elise. Levinas, Judaism, and the feminine: The silent footsteps of Rebecca. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2003.

Kanter, Rosabeth Moss, and Marcia Millman, eds. In Another Voice. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press, 1975.

Kanter, Rosabeth Moss. Men and Women of the Corporation. New York: Basic Books, 1977.

Kaufman, Debra Renee, and Barbara Richardson. Achievement and Women. New York: The Free Press, 1982.

Kaufman, Debra Renee. “Engendering Family Theory: Toward a Feminist-Interpretive Perspective.” In Fashioning Family Theory, edited by J. Sprey, 107-136. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1990.

Kaufman, Debra Renee. “Introduction: Gender, Scholarship and the Holocaust.” Contemporary Jewry, Vol. 17, No. 1 (1996).

Kaufman, Debra Renee. “The Holocaust and Sociological inquiry: A Feminist Analysis.” Contemporary Jewry, Vol. 17, No. 1 (1996): 6-17.

Kaufman, Debra Renee. Rachel’s Daughters. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1991; reprinted 1993.

Keller, Evelyn Fox. “Gender and Science.” Psychoanalysis and Contemporary Thought 1 (1978): 409–433.

Kessler-Harris, Alice, Kathryn Kish -Sklar and Linda K. Kerber, eds. U.S History as Women's History: New Feminist Essays. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Kessler-Harris, Alice. Out to Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States. Oxford University Press, 1982.

Kim, Helen Kiyong, and Noah Samuel Leavitt. JewAsian: Race, Religion, and Identity for America's Newest Jews. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2016.

Kish-Sklar, Kathryn. Florence Kelley and the Nation's Work: The Rise of Women's Political Culture, 1830–1900. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

Kish-Sklar, Kathryn. Catharine Beecher: A Study in American Domesticity. New Haven and London. Yale University Press, 1973.

Klatch, Rebecca. Women of the New Right. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1988.

Koedt, Anne. “The Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm.” In Radical Feminism, edited by A. Koedt, E. Levine, and A. Rapone. New York: Quadrangle, 1973.

Kolodny, Annette. “Dancing Between Left and Right: Feminism and the Academic Minefield in the 1980s.” Feminist Studies 14 (1988): 455–461.

Komarovsky, Mirra. “Cultural Contradictions and Sex Roles.” American Journal of Sociology vol. 52 (1946): 184–189.

Kranson, Rachel. "From Women's Rights to Religious Freedom: The Women's League for Conservative Judaism and the Politics of Abortion, 1970-1982." Devotions and Desires (2018): 170-192.

Kranson, Rachel, et.al. A Jewish Feminine Mystique? Jewish Women in the Postwar Era. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2010.

Lerner, Gerda. "The Lady and the Mill Girl: Changes in the Status of Women in the Age of Jackson." American Studies, 10, 1 (1969): 5–15.

Lerner, Gerda. Black Women in White America: A Documentary History. New York: Pantheon Books, 1972.

Lerner, Gerda. The Female Experience: An American Documentary. Indianapolis and New York: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1977.

Lerner, Gerda. The Majority Finds Its Past: Placing Women in History. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979.

Levin, Gail. "Beyond the Pale: Jewish identity, radical politics and feminist art in the United States." Journal of Modern Jewish Studies vol. 4 (2005): 205-232.

Levin, Gail, et al., eds. Theresa Bernstein: A Century in Art. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2013.

Levitt, Laura. American Jewish loss after the Holocaust. New York: New York University Press, 2007.

Levitt, Laura, et.al., eds. Impossible images: contemporary art after the Holocaust. New York: New York University Press, 2003.

Levitt, Laura. Jews and Feminism: The Ambivalent Search for Home. New York: Routledge, 1997.

Levitt, Laura, and Miriam Peskowitz, eds. Judaism Since Gender. New York: Routledge, 2014.

Lipman-Blumen, Jean. Gender roles and power. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1984.

Lorber, Judith. Women physicians: Careers, status, and power. New York: Tavistock, 1984.

Mednick, Martha, and Sandra Tangri, eds. “New perspectives on women” Journal of Social Issues, 1972.

Mednick, M. T. "On the politics of psychological constructs: Stop the bandwagon, I want to get off." American Psychologist vol. 44, no. 8, (1989): 1118–1123.

Messer-Davidow, Ellen. Disciplining feminism: From social activism to academic discourse. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002.

National Women’s Studies Association. Liberal Learning and the Women’s Studies Major (1991).

NWSA Directory of Women’s Studies Programs, Women’s Centers and Women’s Research Centers: Publication of the National Women’s Studies Association (1990).

Ochs, Carol. Women and Spirituality. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1983.

Pellegrini, Ann and Janet R. Jakobsen, eds. Love the sin: Sexual regulation and the limits of religious tolerance. Boston: Beacon Press, 2004

Pellegrini, Ann, et al., eds. Queer theory and the Jewish question. New York: Columbia University Press, 2003.

Petchesky, Rosalind. Abortion and Woman’s Choice. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1990.

Plaskow, Judith and Carol Christ, eds. Womanspirit Rising. New York: Harper & Row, 1979.

Rapp, Rayna Reiter, ed. Toward an Anthropology of Women. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1975.

Reinharz, Shulamit. Feminist Methods in Social Research. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Reinharz, Shulamit. On Becoming a Social Scientist. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books, 1983.

Rich, Adrienne. Of Woman Born. New York: Norton, 1976.

Rich, Adrienne. On Lies, Secrets and Silences: Selected Prose 1966–1978. New York: W.W. Norton, 1979.

Ringelheim, Joan. “Preface to the Study of Women and the Holocaust.” Contemporary Jewry, Vol. 17, No. 1 (1996).

Robinson, Kathryn O. “Artemis Guide to Women’s Studies in the U.S.” http://www.artemisguide.com.

Rosaldo, Michele, and Louise Lamphere, eds. Women, Culture and Society. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1974.

Ruth, Sheila. Issues in Feminism. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1985.

Sapiro, Virginia. The Political Integration of Women: Roles, Socialization, and Politics. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1984.

Sered, Susan Starr. Women as ritual experts: The religious lives of elderly Jewish women in Jerusalem. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Schor, Naomi. Breaking the Chain: Women, Theory and French Realist Fiction. New York: Columbia University Press, 1987.

Shohat, Ella, et. al. eds. Dangerous liaisons: Gender, nation, and postcolonial perspectives. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1997.

Shohat, Ella. Talking visions: Multicultural feminism in a transnational age. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001.

Showalter, Elaine. A Literature of Their Own: British Women Novelists from Brontë to Lessing. Princeton University Press (1977)

Showalter, Elaine. The Female Malady: Women, Madness, and English Culture, 1830–1980. New York : Pantheon Books (1985)

Smith, Judith E. "Judy Holliday’s Urban Working-Girl Characters in 1950s Hollywood Film." A Jewish Feminine Mystique: Jewish Women in Postwar America, edited by Hasia Diner, Shira Kohn, and Rachel Kranson, 160-176. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2010.

Sochen, June. Cafeteria America: new identities in contemporary life. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press, 1988.

Sochen, June. Consecrate Every Day: The Public Lives of Jewish American Women, 1880-1980. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1981.

Sochen, June. The New Woman: Feminism in Greenwich Village, 1910-1920. New York: Quadrangle Books, 1972.

Stacey, Judith. Brave New Families. New York: Basic Books, 1993.

Unger, Rhoda. Woman: Dependent or Independent Variable? New York: Psychological Dimensions, 1975.

Weitzman, Lenore J., and Dalia Ofer eds. Women in the Holocaust. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998.

Wexler, Laura. Tender violence: Domestic visions in an age of US imperialism. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

Weinberg, Sydney Stahl. The World of our Mothers: The Lives of Jewish Immigrant Women. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1988.

Wolf, Diane L. Beyond Anne Frank: Hidden children and postwar families in Holland. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007.

Wolf, Diane L. and Judith Gerson, eds. Sociology Confronts the Holocaust: Memories and Identities in Jewish Diasporas. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007.