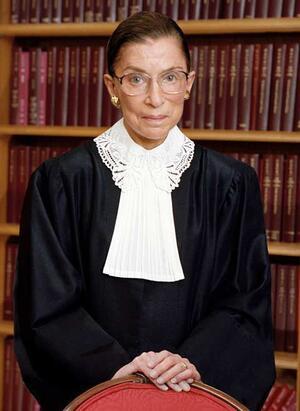

Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the first Jewish woman on the Supreme Court (and only the second woman on the Court), is a unique figure in the history of American law and of the twentieth- century women’s rights movement. After excelling at Harvard and Columbia law schools, she struggled to find a job because of sexism and antisemitism. While teaching at Rutgers University, she took on a few cases for the American Civil Liberties Union, then founded the ACLU’s Women’s Rights project, where her storied career as an advocate for gender equality began. In 1980, she was confirmed for the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, and in 1993 she became an associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. In later years, she became a cultural icon to countless younger women and social justice advocates.

Introduction

Ruth Bader Ginsburg is a unique figure in the history of American law, and indeed, of the twentieth-century women’s rights movement. She was the founder in 1972 of the American Civil Liberties Union Women’s Rights Project, where she served until her appointment to the federal bench. Her record as an advocate before the Supreme Court was outstanding; she argued six cases before the court, winning five. Had she had done nothing else in her life, that alone would have been an extraordinary legacy. She was then confirmed for the United States District Court for the District of Columbia in 1980, and from there, as an associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court in 1993; the first Jewish woman on the Supreme Court, she served for twenty-seven years.

Background

In some way, Ginsburg’s background prefigured her extraordinary work in the public interest. She was born on March 15, 1933, in Brooklyn, New York, to Nathan and Celia (Amster) Bader. Nathan had immigrated to the United States from Russia at the age of thirteen. Celia, the fourth of seven children, was the first to be born in the United States, four months after the Bader family’s arrival in the United States. She worked in a garment factory to support her family and enable her brother to go to college.

Ginsburg credits her mother with impressing on her the importance of achievement and independence, as well as the value of reading and aiding the poor and needy. Indeed, at her swearing-in as a Supreme Court justice, Ginsburg expressed gratitude to her mother, praying that she might “be all that she would have been had she lived in an age when women could aspire and achieve and daughters are cherished as much as sons” (Antler, 329).

Ginsburg’s path, though not as challenging as her mother’s, was not an easy one. She graduated from James Madison High School one day before her mother died of cervical cancer. She attended Cornell on scholarship, where she met and married Martin D. Ginsburg. She would later say that Marty was “the only young man I dated who cared that I had a brain,” which was an understatement (Foussianes). They became a two-career family, unusual for the time, with Marty extraordinarily supportive of Ginsburg’s work. He was the family’s cook, and Ginsburg’s cheerleader at every level, including when she was named as a possible candidate for the Supreme Court. He was, as one writer described, “the platonic ideal of a supportive husband” (Foussianes).

After college, Ginsburg worked for the Social Security office in Oklahoma, where Martin was serving in the military. After she revealed her pregnancy to the administrators, she was demoted. Later, Ginsburg and Martin both attended Harvard Law School; she was one of only nine women in a class of over five hundred. During her second year, Martin was diagnosed with a rare cancer; Ginsburg copied his notes and typed his papers while he had his treatment. Martin recovered; Ginsburg made law review. Following Martin to New York, she transferred to Columbia Law School. Although she had tied for first place in her class at Columbia, she received no job offers; as she later said, “In the Fifties, the traditional law firms were just beginning to turn around on hiring Jews. But to be a woman, a Jew and a mother to boot–that combination was a bit too much” (Antler, 330).

Ginsburg joined the faculty of Rutgers University Law School in 1963 as an assistant professor, and in 1971 she became a lecturer at Harvard Law School, where she taught the school’s first course on women’s rights. In 1972, Ginsburg became the first tenured female law professor at Columbia Law School.

As a young lawyer, juggling family (by then two children) and teaching, Ginsburg took on a few cases for the American Civil Liberties Union. In 1972, she co- founded the Women’s Rights project, where her storied career as an advocate began.

Vision of Gender Equality

Ginsburg’s vision of gender equality was decades ahead of her time. In their 1974 Women and the Law textbook, Justice Ginsburg and her coauthors outlined their vision of gender equality. This vision went beyond simply empowering women to compete for stereotypically “men’s” jobs (like lawyer, for example). Their efforts were aimed at enabling “members of both sexes” to assume all of society’s roles. Of course, stereotypes of women as “mother, wife, girlfriend, nurse, helper, the symbolic identification of authority with maleness, from deep resonant voices to patriarchal gods, the relative absence of working women as competent and successful role models,” skewed women’s view of what was possible. But these attitudes, they suggested, impeded men as well, who were “no less trapped in their assigned roles”:

[T]he very assurance of their dominance marks out for even greater social disapproval men whose unconventional interests and abilities lead them to choose different lifestyles....Only when men and woman are able to see themselves and each other without preconceptions, as human beings will the underlying support for sex based discrimination disappear. (Davidson, Ginsburg, and Kay; Kay would later write that the quoted comments were signed by all three authors but were written by Justice Ginsburg alone.)

When school administrators wanted Ginsburg to come to school to discuss her son’s misconduct, she famously said, “This child has two parents” (Joyce).

The theory was radical for the 1970s, but the approach—embodied by then-lawyer Ginsburg’s litigation strategy—was incremental, not unlike Justice Ginsburg’s judging. While she continued to be animated by her life’s passion for equality when she joined the court, she was not the “activist” caricature some in the media later portrayed her to be. She was anxious to avoid upending precedent, determined to be respectful of the opinions of her colleagues. She believed in incremental legal change and emphasized the limited role that a court plays in a constitutional democracy. In Ginsburg’s understanding, courts have a critical role to play in identifying new understandings of the Constitution, but they must do so by “measured motions” (“Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Speaking in a Judicial Voice”). They are part of a dialogue with other organs of government and with the people as well. At her confirmation hearing, she put it more succinctly: a judge should “strive to write opinions that both ‘get it right’ and ‘keep it tight’” (Nomination of Ruth Bader Ginsburg).

That approach—keeping it tight—surely did not mean originalism, the judicial philosophy that focuses on the language of the Constitution and the meaning it had at the time of the Framers, a time when only white propertied males were a member of the polity. To Justice Ginsburg, the Constitution should be read “as belonging to a global twenty-first century, not as fixed forever by eighteenth-century understandings” (“A Decent Respect for the Opinions of [Human]kind”). She would apply the court’s precedents but take pains to situate them in their social and historical context, tirelessly recounting the history of gender-based classifications and their impact. Still, she was, as the New York Times’s Linda Greenhouse described at the time of her confirmation, a “judicial-restraint liberal” who combines a “muscular and broadly inclusive Constitution” with a “pragmatist’s sense that the most efficacious way of achieving the Constitution’s highest potential as an engine of social progress is not necessarily through the exercise of judicial supremacy” (Greenhouse; Valentine).

United States v. Virginia: Women’s Access to the Virginia Military Institute

It is difficult to imagine a case more significant for gender discrimination law than the one Justice Ginsburg confronted only three years into her tenure on the Court. In United States v. Virginia, Justice Ginsburg’s work as a litigator, including the precedents she had helped generate, aligned with the positions of six of her judicial colleagues. She was tasked with writing the majority opinion. Her impact as a lawyer/scholar/judge—all seemingly playing out in the case before her—could not have been clearer.

The United States government challenged Virginia’s practice of admitting only men to its prestigious military college, the Virginia Military Institute. Justice Ginsburg catalogued the usual justifications for gender discrimination that would not pass muster–justifications she had challenged throughout her career. The justification must be genuine, not an after-the-fact rationalization or the result of “overbroad generalizations about the different talents, capacities, or preferences of males and females.” Nor was it sufficient that the government’s motivations be “benign.” Ostensibly benign justifications, grounded in stereotypes about men and women, had burdened women’s full participation in public life for decades, as litigator Ginsburg had shown over and over again. Even physical differences between men and women—namely, Virginia’s claim that most women lacked the physical ability to participate in VMI’s rigorous training regime —would be scrutinized. As Justice Ginsburg said in Virginia:

“Inherent differences” between men and women, we have come to appreciate, remain cause for celebration, but not for denigration of the members of either sex or for artificial constraints on an individual's opportunity. Sex classifications may be used to compensate women for particular economic disabilities [they have] suffered,…but such classifications may not be used, as they once were, …to create or perpetuate the legal, social, and economic inferiority of women (Virgina).

While there were surely physical differences between men and women, how the law dealt with them was socially constructed—not innate—and based on old-fashioned stereotypes. A woman’s ability to bear children, and the traditional division of labor associated with it, too often contributed to “the legal, social and economic inferiority of women.” Ginsburg had said it before as an advocate. This time, and over and over again during her tenure on the Court, she said it as a Justice.

The analysis was classic Ginsburg: a lengthy description of the school, its prestige, its role in preparing men and only men for high-status roles in government and industry. VMI’s exclusion of women violated the Equal Protection clause; the state had “reserv[ed] exclusively to men” an “incomparable…college” and “the unique educational opportunities [it] affords.” Opportunities, it goes without saying, that were not remotely available to women. And it resonated with Justice Ginsburg’s early work, even her early Gender and Law text: There should be no separate spheres for men and women under the law. Distinctions based on what “most” men or women do, on the choices that “most” of them make, are an impediment to full equality.

Gratz v. Bollinger: Championing Affirmative Action

In cases challenging racial affirmative action programs, like Gratz v. Bollinger, in which the majority struck down the University of Michigan’s freshman admission programs, Justice Ginsburg dissented, reciting the data that showed the persistence of racial inequity in housing, education, and employment, the lingering effects of “centuries of law-sanctioned inequality.” “We are,” she said, “not far distant from an overtly discriminatory past, and the effects of centuries of law-sanctioned inequality remain painfully evidence in our communities and schools.” Her work prefigured more recent debates about systemic racial discrimination.

Lilly Ledbetter v. The Good Year Tire & Rubber Co.: Gender Equity in Pay

Ginsburg brought her own experiences to bear on cases, insisting that legal rules be understood in “the realities of the workplace,” a reality she understood well. Her position was nowhere clearer than in Lilly Ledbetter v. The Good Year Tire & Rubber Co., Inc. Ledbetter challenged the fact that she had not been paid equally with similarly situated men over a period of time; past pay decisions were based on plainly pretextual evaluations. The Court rejected the challenge, finding that each separate paycheck comprised a single violation; the first unequal paychecks may well have been the product of discrimination, but since Ledbetter sued only after she found out about the differential many years later, she had sued too late. Ginsburg dissented, using more passionate language than her usual measured tone in her stinging oral dissent, again reciting the real world in which pay disparities occur.

Pay disparities often occur, as they did in Ledbetter's case, in small increments; cause to suspect that discrimination is at work develops only over time. Comparative pay information, moreover, is often hidden from the employee's view. Employers may keep under wraps the pay differentials maintained among supervisors, no less the reasons for those differentials. Small initial discrepancies may not be seen as meet for a federal case, particularly when the employee, trying to succeed in a nontraditional environment, is averse to making waves.

Goodwin Liu, a former Ginsburg clerk who became a justice on the California Supreme Court, said that when Justice Ginsburg was recounting what had happened to Ledbetter, she was also telling her own story. "Here she is, the one woman of a nine-member body, describing the get-along imperative and the desire not to make waves felt by the one woman among 16 men. It's as if after 15 years on the court, she's finally voicing some complaints of her own” (Greenhouse).

The message was heard by the Congress. In 2009, Congress passed the Lilly Ledbetter law, amending Title VII and stating that the statute of limitations for filing an equal pay lawsuit resets with each new paycheck affected by the original discriminatory act.

Gonzales v. Carhart: The Right to and Regulation of Abortion

On the same day as the Ledbetter dissent, Ginsburg issued another oral dissent, her tone even sharper. Gonzales v. Carhart involved a federal statute banning a particular method for ending a pregnancy in the second trimester (the so-called “partial birth abortion”), oft-maligned but rarely used in practice. The majority rejected a constitutional challenge to the statute. The Court concluded that barring this method of abortion was not an undue burden on the right to choose abortion, that it appropriately reflected the state’s concern for fetal life and even protected the mother’s interest: Since the abortion decision is so difficult and one “which some women come to regret,” doctors should keep specifics about the procedure from them, depriving them of an informed choice.

Justice Ginsburg dissented, arguing that the Court had violated its own precedents with this decision. It blessed a prohibition with no exception safeguarding a woman’s health, and it did so without even preserving fetal life. It simply banned one method of ending a pregnancy. And true to form, Justice Ginsburg then situated her opinion in her own equality jurisprudence. She had previously criticized Roe v. Wade because it had announced a constitutional right in a precipitous way, not in the incremental fashion that she favored as a lawyer and favors as a justice. The right to choose abortion, she believed, was part and parcel of an analysis of gender, hierarchy, and caste under the Equal Protection Clause, rather than the Roe v. Wade analysis of due process. Abortion implicates “a woman's autonomy to determine her life's course, and thus to enjoy equal citizenship stature.”

But Justice Ginsburg chafed not simply at the outcome, but also about the majority’s paternalistic tone; she had sadly heard it before. While the Court claimed to care that doctors would not share with women the details about how the abortion would be performed, its solution in her view was worse. By barring the procedure, it took from women their right to make an autonomous choice, a pattern that fit within the paternalism of the Supreme Court’s earlier opinions, the ones she had aggressively challenged. And she ended with an ominous warning about the future of Roe v. Wade:

The Court's hostility to the right Roe … secured is not concealed. Throughout, the opinion refers to obstetrician-gynecologists and surgeons who perform abortions not by the titles of their medical specialties, but by the pejorative label ‘abortion doctor’… A fetus is described as an ‘unborn child,’ and as a ‘baby’; second-trimester, previability abortions are referred to as ‘late-term’; and the reasoned medical judgments of highly trained doctors are dismissed as ‘preferences’ motivated by ‘mere convenience’ …. Instead of the heightened scrutiny we have previously applied, the Court determines that a “rational” ground is enough to uphold the Act…. And, most troubling, Casey's principles, confirming the continuing vitality of ‘the essential holding of Roe,’ are merely ‘assume[d]’ for the moment, rather than ‘retained’ or ‘reaffirmed.’

Judicial Influence

Ginsburg’s judicial influence has to be measured not simply in the decisions she authored, but also in the decisions of her colleagues and lower-court judges. It extends to areas far beyond gender and race discrimination, including cases about access to justice, disability discrimination, and the right to counsel.

While Ginsburg had been a reluctant dissenter (Ledbetter and Bollinger aside), , in later years her role changed with the court’s shifting membership. She dissented more and more, including a dissent of monumental significance in Shelby County v. Holder. At issue was the fate of the Voting Rights Act (VRA), which sits among the most consequential pieces of civil rights legislation in American history. The majority threw out the preclearance mechanism in which states with a history of discrimination had to seek approval for changes in voting laws that impacted African Americans. It was no longer necessary in modern America, they said.

Justice Ginsburg’s dissent was biting: “Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.” A long and visceral dissent, tirelessly examining the instances of voter disenfranchisement through the present day, was capped off with a simple summation: “In my judgment, the Court errs egregiously by overriding Congress’ decision.”

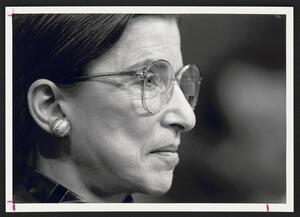

The “Notorious RBG”

Ginsburg’s contributions to the law were nothing short of monumental, but she never could have predicted the cultural icon she would become, the subject of a critically acclaimed documentary, “RBG,” featuring quotes from her cases and her speeches and highlighting her indomitable spirit with clips from her workouts with her trainer. And no one could have imagined the Saturday Night Live spoof; or the feature film “On the Basis of Sex,” starring Felicity Jones as Ginsburg; or the internet meme mirroring the deceased rapper Biggie Smalls’ meme (“Notorious B.I.G.”). She was the “Notorious RBG,” a beloved figure to new generations of young feminists and activists.

“Justice, justice shalt thou pursue.”

Vigil for Ruth Bader Ginsburg outside the Supreme Court building, September 2020. Courtesy © Lloyd Wolf.

On the wall in Ginsburg’s office hung the biblical saying “Justice, justice shalt thou pursue.” Although she was not religiously observant, she proudly identified as a Jew: “I am a judge, born, raised and proud of being a Jew,” she said, in an address to the American Jewish Committee (Antler, 332). And she added, a fitting coda to her life’s work, “the demand for justice runs through the entirety of the Jewish tradition.”

This unquenchable demand for justice was reflected in the cases Ginsburg had argued, the causes she had advocated, and the Court’s decisions she authored. As Linda Greenhouse put it, Justice Ginsburg always “played a long game” with the “ultimate goal”—equality between the sexes, as well as racial equity, access to justice, procedural fairness—“constantly in view.”

It was indeed “a long game,” with extraordinary milestones and a remarkable legacy. Ruth Bader Ginsburg died on September 18, 2020, of complications from pancreatic cancer. Her death prompted outpourings of grief and countless tributes from women young and old, feminists and civil rights activists, and a wide range of people concerned with social justice.

Selected Works by Ruth Bader Ginsburg

With Kenneth M. Davidson and Herma H. Kay. Sex-Based Discrimination: Test, Cases and Materials. Eagen, MN: West Publishing Co., 1974.

“A Decent Respect for the Opinions of [Human]kind”: The Value of a Comparative Perspective in Constitutional Adjudication.” Keynote address at the Ninety-Ninth Annua Meeting of the American Society of International Law, April 1, 2005.

“Constitutional Adjudication in the United States as A Means of Advancing the Equal Stature of Men and Women Under the Law.” Hofstra Law Review 263, 265 (1997).

Antler, Joyce. The Journey Home, Jewish Women and the American Century. New York: Free Press, 1997.

Foussianes, Chloe. “How Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s Late Husband, Marty, Helped Her Reach Her Potential.” Town & Country, September 19, 2020.

Joyce, Amy. “Ruth Bader Ginsburg was the model we working moms needed.” Washington Post, September 19, 2020; https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/2020/09/19/ruth-bader-ginsburg-working-mom-icon/.

Greenhouse, Linda. “The Supreme Court: A Sense of Judicial Limits.” New York Times July 22, 1993: A1.

Nomination of Ruth Bader Ginsburg to Be Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States: Hearing Before the S. Comm. On the Judiciary, 103d Cong. 53 (1993) (Statement of Ruth Bader Ginsburg).

“Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Speaking in a Judicial Voice.” New York University Law Review 1185, 1198 (1992).

Valentine, Sarah E. “Ruth Bader Ginsburg: An Annotated Bibliography.” New York City Law Review 391, 395 (2004).