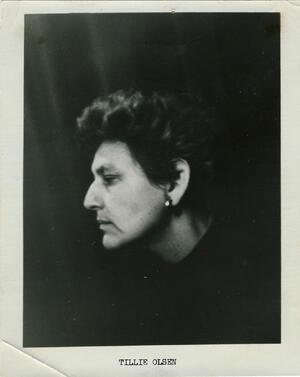

Tillie Olsen

Tillie Olsen's hand-writing was so tiny you almost needed a magnifying glass to read her patchwork of words, yet her influence on my life was enormous. I remember almost everything about her visit to Washington University where I was a student in 1976. Susan Koppelman, the first feminist in Washington University's administration, brought Tillie Olsen and other women authors, such as May Sarton, Alice Walker, and Adrienne Rich for a convocation meant to inspire us—students, future feminists, and activists.

In a rather small hall, the windows lashed with rain, Tillie read Tell Me a Riddle out loud to 600 people. We were all in tears, including Tillie. For me, that day was life-changing. My then partner and I sat in silence, dreaming dreams. I spent the next five years making Tell Me a Riddle into a movie. We took the book to 5,000 people, asking each to help turn this story into a film. Virtually every woman we reached fell in love—and hate—with the gnarled roots of the struggle of Eva and David, Tell Me a Riddle's protagonists.

A daughter of immigrants and a working mother starved for time to write, Tillie Olsen drew from her personal experiences to create a small but influential body of work. Her first published book, Tell Me a Riddle (1961), which went to print when Tillie was 50, contained a short story, "I Stand Here Ironing," in which the narrator painfully recounts her difficult relationship with her daughter and the frustrations of motherhood and poverty.

At the time of the book's publication Tillie was applauded by critics as a short story writer of immense talent. Tillie's working class roots and leftist political involvement were never far from her life and work. Her popularity within the rising women's movement was in part due to the importance of bringing a working class perspective to a movement that struggled with privileged roots and limited reach.

Tell Me a Riddle was a testament to the economic, political, and personal turmoil involved in pulling away as a mother to write. As author Margaret Atwood observes of Tillie's work, "It begins with an account of her own long, circumstantially enforced silence. She did not write for a very simple reason: A day has 24 hours."

Personally, Tillie gave me the chance to create a new life with her life's best work. Even then, Tillie knew that the scope of her work as a writer would never surpass Tell Me a Riddle. She informed me that four other filmmakers had tried to "get her book." Tillie held out, knowing that the power to re-interpret would potentially ruin her masterpiece. Yet, working with triple Academy Award winners—and blacklist survivors like Lee Grant, Melvyn Douglas, and Lila Kedrova, we renewed the spirit of her book on the screen, bringing the social issues forward in time. We told the tale in the present and past, providing Melvyn Douglas his last film as an actor, and Lee her first—and only feature film as a director.

During these years of the film's making, and for the next quarter century, I maintained a close relationship with Tillie, perhaps writing and calling a little less as the years, documentaries, and family intervened. One time, Tillie began talking in general about her project, about the gaps in work, and productivity especially for women writers between books. It "took me so long to begin writing, to break out of my own silences and write again," she explained. She spoke about filling the well of inspiration with love, grief, children, and life itself; to have enough life-material for writers to draw from. She talked about author Katherine Anne Porter's masterpiece, Ship of Fools. Tillie told me how on a cruise to Bremen, Germany in 1931, Porter had met Hermann Goring, a leading member of the Nazi party. Around the time of this encounter, Porter outlined all the main characters in Ship of Fools. Yet, Porter turned in the completed book only under pressure from her publisher—in 1962. Her nemesis, her masterpiece, her first and only novel, and her long silence inspired Tillie's next work.

That book, Silences (1978), Tillie Olsen's own masterwork of non-fiction, reveals the impediments and pressures that writers face because of sex, race or social class. Reviewing Silences in the New York Times Book Review, Margaret Atwood attributes Ms. Olsen's relatively small output to a "grueling obstacle course" experienced by many women writers.

Today, twenty-five years after making Tell Me a Riddle, after breaking down the glass ceilings and concrete walls of the studio system, I still struggle to get each new film made. Yet, today we have made progress: Instead of one percent of all movies being directed by women, it's up to seven percent. Progress, but not yet victory.

Twenty-five years later women have changed but not yet transformed our role in media enough. Perhaps the next generation can continue the struggle. Today, we face an even greater backlash against feminism than we did during those heady days of the seventies. Tillie was a leader in the women's movement from the time she began writing until her death. Perhaps the next generation will continue the struggle, reminding today's young women that their opportunities for education, work, and the power to choose how to live their lives, exist in part, because of Tillie Olsen, Alice Walker, Isabel Allende, and many others. Today they must choose to continue to reach across lines of class, race, and religion to renew our movement devoted to equality and freedom for women.