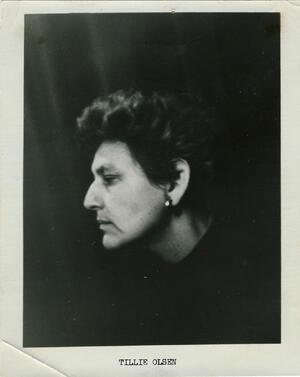

Tillie Olsen

A daughter of Bundist Russian-Jewish immigrants, Tillie Olsen drew from her personal experiences to create a small but influential body of work. Her first book, Tell Me a Riddle (1961). was met with wild success, earning an O. Henry award and inspiring an Academy Award-winning movie. Olsen continued to write while teaching literature at Amherst College, Stanford University, and Kenyon College. Her rediscovery and reprinting of Rebecca Harding Davis’s 1861 novel Life in the Iron Mills led Olsen to recover the work of more women authors and lobby for literary gender parity in academia. This work, combined with her own struggles to write despite economic and family pressures, led to Silences, her groundbreaking exploration of the absence of women, minorities, and working-class writers from the literary canon.

Family and Early Life

Writer Tillie Olsen was a leading spokesperson for silent and oppressed workers, especially creative women whose daily routine stifles their expression.

Tillie Lerner Olsen was born in Mead or Wahoo, Nebraska, in 1912 or 1913 (the most often used birthday is January 14, 1913). She was the daughter of Samuel and Ida (Goldberg) Lerner, from Odessa and Minsk, and had five siblings, Jan, Harry, Lillian, Eugene, and Vicki.

While in Russia, Samuel Lerner worked for the Bund, a Jewish socialist movement. He and his wife came separately to America after the failure of the 1905 revolution, in which they had participated. They met again in New York, then finally reunited in Mead, Nebraska, where Lerner was a tenant farmer, sometime between 1908 and 1910. By 1917, the family had moved thirty miles to a working-class neighborhood in Omaha. Lerner became a peddler, then ran the Silver Star Confectionery, where Olsen remembers shelling almonds for candies. He then found work as a painter and paperhanger.

Samuel Lerner, who held strong political and economic views, served as secretary of the Nebraska Socialist Party and, in 1928, was its candidate for lieutenant governor. He was an active member of the Workmen’s Circle in Omaha and organized regional midwestern events.

Tillie Olsen’s Russian Jewish heritage, radical political roots, and Midwest environment left a lasting impression on her. Her sense of class consciousness and social agenda emerged from her radical heritage, which downplayed Jewish religious observance and emphasized the social agenda of yidishkayt [Jewish heritage]. (Her father was an atheist to the end of his life, and she went to Socialist Sunday school.) Olsen claimed that her values came from her yidishkayt.

Tillie attended Central High School in Omaha but dropped out in 1929 in the eleventh grade. Coming from an immigrant working-class background, she saw at school how people from the other side of the track lived. She was alienated and marginalized, a compound of Jewish, working class, immigrant, poor, and female. Although she did not graduate, a humor column she wrote for the high school paper credits the rigorous reading and writing requirements and intellectual excitement of the school, and particularly her teachers Sara Vore Taylor and Autumn Davies, for igniting a passion to read and write. But political activism and birth of a child out of wedlock intervened.

Radicalism and Communist Involvement

The Depression intensified Tillie’s radicalism. In 1931, she joined the Young Communist League. In 1932, active in the Omaha Council of the Unemployed, she was identified in the newspaper under aliases such as Teresa Landale and Theta Larimore. She then moved to Kansas City, where she worked in a tie factory. She was arrested for leafleting and served five months in jail. She worked as a tie presser, hack writer, model, mother’s helper, ice-cream packer, book clerk, waitress, punch-press operator, and temporary office helper. She also worked in meat packing in Omaha, Kansas City, and St. Joseph.

In 1933, at the age of nineteen, Tillie left Omaha to recuperate from pleurisy in Faribault, Minnesota, and started writing Yonnondio: From the Thirties. She then moved to California, where she was jailed for two weeks following a police raid against radicals. She married Jack Olsen (né Olshansky), a Kiev-born printer and strong union advocate who had also been a member of the Young Communist League. They had four daughters: Carla, Julie, Katherine Jo, and Laurie. Jack Olsen died in 1989 at age seventy-seven.

Olsen’s Literary Works

Olsen returned to writing in the mid-1950s after her children were grown. She was awarded a writing fellowship at Stanford in 1956–1957 and a Ford Foundation grant in literature in 1959. Her short story collection Tell Me a Riddle has become an American classic. The title story, “Tell Me a Riddle,” won the O. Henry Short Story Award in 1961 and became an Academy Award–winning movie in 1980, starring Melvyn Douglas and Lila Kedrova.

Olsen rediscovered and reprinted the 1861 Rebecca Harding Davis story Life in the Iron Mills in 1972. Her Depression novel Yonnondio: From the Thirties, started in 1933 and finished in the late 1950s, was published in 1974. The novel is about the lives of the midwestern poor. It follows the Holbrook family’s migration from Wyoming to the Dakotas, ending in the south Omaha slaughterhouses. Silences, begun in 1962 and published in 1978, narrates the difficulty women writers saddled with the burdens of raising and supporting a family have faced in a patriarchal society. It is a lament for unfulfilled promise and for stunted talent.

Olsen was an internationalist, believing in one human race without religious, racial, or ethnic divisions. Her parents were socialists, but she became a communist, which may have created additional alienation. She joined and quit the Communist Party more than once and was critical of its policies. During World War II, she was president of the California CIO Women’s Auxiliary. She was an outspoken advocate of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. She exhibited a Jewish “secular messianic utopianism,” which came from her immigrant parents. (Lyons in Nelson and Huse, p. 144).

Awards, Honors, and Critical Acclaim

Olsen taught in writers’ programs at Amherst College, Stanford University, and Kenyon College; she was a fellow of the Radcliffe Institute, a writer-in-residence at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and a regents lecturer at the University of California; and she received National Endowment for the Arts awards, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a doctor of arts and letters degree from the University of Nebraska (1979). In 1991, she received the Mari Sandoz Award of the Nebraska Library Association, and she was the winner of the $25,000 Rea Award from the Dungannon Foundation in New York for best short story of 1994. The January 3, 1994, issue of Newsweek commemorated the magazine’s sixtieth anniversary with an article entitled “The First Sixty Years.” In this article, the editors chose authors who were emblematic of the decades: For the 1930s, it was Tillie Olsen. Public acknowledgment has not been universal, however, and Harold Bloom has been criticized for not including Olsen in The Western Canon: Books and Schools of the Ages (1994).

Death and Literary Legacy

Olsen passed away on January 1, 2007, in Oakland, California. The New York Times, NPR, and the LA Times all published obituaries memorializing Olsen after her death from years of declining health. Towards the end of her life, Olsen lived in San Francisco, traveled widely, and visited Omaha and Lincoln, Nebraska, several times. She acknowledged that some of her writing is autobiographical, much of it deriving from her early life in Omaha. Nevertheless, her work addresses deep universal issues of gender, class, religious identity, and social consciousness.

SELECTED WORKS BY TILLE OLSEN

Silences (1978).

Tell Me a Riddle (1961. Movie, 1981).

Yonnondio: From the Thirties (1974).

Atwood, Margaret. "Obstacle Course." Rev. of Silences, by Tillie Olsen. Huse and Nelson (1994): 250-251.

Coiner, Constance. Better Read: The Writing and Resistance of Tillie Olsen and Meridel Le Sueur (1995).

Contemporary Authors Vol. 1 (1981): 485; EJ 1982–1985.

Fishkin, Shelley Fisher. Feminist Engagements: Forays in American Literature and Culture. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

Herring, Scott. "Tillie Olsen, Unfinished (Slow Writing from the Seventies)." Studies in American Fiction 37, no. 1 (Spring, 2010): 81-99,153.

Johnston, Lisa N. "Tillie Olsen: A Heart in Action." Library Journal (2009).

Lee, Corinna K. "Documents of proletarian fiction: Tillie Olsen's Yonnondio: from the thirties." Journal of Modern Literature 36, no. 4 (2013): 113-132.

Lyons, Bonnie. “Tillie Olsen: The Writer as a Jewish Woman.” Studies in Jewish American Literature 5 (1986): 89–102.

Mazurek, Raymond A. "Rebecca Harding Davis, Tillie Olsen, and Working-Class Representation." College Literature 44, no. 3 (Summer, 2017): 436-458.

Nebraska Jewish Historical Society Archives, Omaha; Nelson, Kay Hoyle, and Nancy Huse, eds. The Critical Response to Tillie Olsen (1994).

Olsen, Tillie. Correspondence with author; Omaha Jewish Press (various issues).

Orr, Elaine Neil. Tillie Olsen and the Feminist Spiritual Vision (1987).

Pratt, Linda Ray. “The Circumstances of Silence: Literary Representation and Tillie Olsen’s Omaha Past.” In The Critical Response to Tillie Olsen, edited by Kay Hoyle Nelson and Nancy Huse (1994).

Pratt, Linda Ray. “Tillie Olsen’s Omaha Heritage: A History Becomes Literature.” Memories of the Jewish Midwest 5 (1989): 1–16.

Reid, Panthea. Tillie Olsen: One Woman, Many Riddles. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2010.

Schocket, Eric. Vanishing Moments: Class and American Literature. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2006.

“The ’30s. A Vision of Fear and Hope. Tillie Olsen.” Newsweek (January 3, 1994): 26–27.