Bette Midler

Bette Midler is part of a lineage of twentieth-century bawdy entertainers. Born in a small Hawaiian town where hers was the only Jewish family, Midler ultimately starred in over twenty films and released twenty-four records. She gained her first devoted following at New York City’s Continental Baths—a gathering place for gay men, where she developed the campy and outrageous persona “The Divine Miss M.” Albums and live concert tours raised her star until by 1979 she was the lead in the award-winning feature film The Rose. Her film career expanded into her own production company. Midler is known for her versatile showmanship, flowing between genres, media, time periods, comedy, and drama, but with a signature theatricality and winking humor.

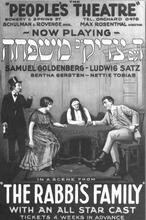

Bette Midler is part of a full and fabulous lineage of early twentieth-century bawdy Jewish entertainers such as Belle Barth and Sophie Tucker. Midler even does an imitation of Tucker in her persona as Delores De Lago, the lowest form of show business and the toast of Chicago. But beyond her brassy “trash-with-flash” persona, Midler’s career showcases remarkable versatility, hop-scotching across genres, eras, and media.

Early Life

Due to her performances at the baths, Bette Midler earned the nickname Bathhouse Betty. It was at the Continental, accompanied by pianist Barry Manilow, that she created her stage persona the Divine Miss M.

Born in Honolulu on December 1, 1945, to Fred and Ruth Midler, Bette (named after Bette Davis) was an outsider in many ways. She was the third daughter in a lower-middle-class family where both parents had to devote much of their attention to her younger brother, who had special needs. In school, she felt like an outsider as well. Her family’s Jews of European origin and their descendants, including most of North and South American Jewry.Ashkenazi Jewish background set her apart from her mostly Polynesian neighbors.

Witty responses, quick retorts, and a ready smile became Midler’s defense against unpleasant home and school realities. “I learned that I could be popular by making people laugh. I became a clown to win people’s acceptance,” she later remarked (Mair). Although she was elected senior class president and graduated as the class valedictorian, she always felt “othered.”

While working in a pineapple-canning factory and studying at the University of Hawaii, Midler got a small part in the film Hawaii (released in 1966), prompting her to move to the mainland for a career in show business. After multiple rejections, she finally gained a small part in the chorus of Broadway’s Fiddler on the Roof in 1965 and later was given the part of Tevye’s eldest daughter, Tsaytl. She stayed with the show for three years. But her real “break” was a singing gig at the Continental Baths, a gay gathering place where entertainers performed near the pool area.

It was in this setting—supported by then-little-known piano player Barry Manilow—that Midler (whom critic Rex Reed dubbed “Jewish Tinker Bell”) developed many of the outrageous personae that became the standards of her concert show and the basis for her spectacular success. The most famous of these personae is The Divine Miss M, a giddily gaudy woman who wore black lace bustiers and gold lamé pedal pushers while singing songs of the 1940s and 1950s. In between songs, she told off-color jokes, charging the audience with her humor, energy, and theatricality.

In the late 1960s, while Midler flourished at the Continental Baths, the country was experiencing a social upheaval. Midler’s enthusiastic irreverence and eagerness to publicly discuss sexuality fit into the revolutionary changes in sexual behavior and discourse. Her support for gay men, who have remained a loyal contingent of fans of her shows and records, added to her free and flamboyant persona.

Midler in the Mainstream

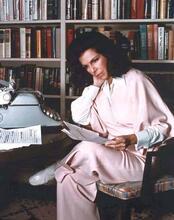

Bette Midler's first TV special on CBS. She won an Emmy for "Outstanding Achievement in Tape Sound Mixing" and one for "Outstanding Special - Comedy - Variety or Music."

An appearance on the Johnny Carson Show in 1970 helped give Midler a national audience, opening up a variety of media. Her live performance career took off as she garnered rave reviews in the role of the Acid Queen in the Seattle Opera’s premiere of the first rock opera, Tommy, in 1971. She also developed a comedy resume that would make any stand-up envious, performing at institutions like Downstairs at the Upstairs, the Copacabana, The Improv, and The Bitter End, and even opening for Mort Sahl at Mr. Kelly’s Chicago.

In 1972, Aaron Russo became Midler’s manager; he is credited with organizing her career and arranging the tours and records (The Divine Miss M [1972] and Bette Midler [1973]) that galvanized her stardom. They had a tumultuous personal and professional relationship, however, which Midler channeled in her tour-de-force performance as a Janis Joplin-like character in The Rose (1979). Midler’s film debut, The Rose depicted the incredible stress associated with touring, and the added tension of a domineering manager. The performance was awarded a BAFTA and Oscar nomination, two Golden Globes, and a Grammy. Throughout the 1970s, Midler continued to win popular and critical acclaim with the Emmy-winning TV special Ol’ Red Hair is Back and the Tony-award-winning revue Clams on the Half Shell. By 1979, she broke with Russo and took charge of her own career.

Unfortunately, Midler’s break with Russo was followed by two unsuccessful film projects—the filmed adaptation of her stage show Divine Madness and the ill-reviewed Jinxed (1980). The tepid reception put her film career on pause for four years, inflaming Midler’s insecurity and depression.

A deleted scene from Bette Midler's "Divine Madness."

Midler’s personal life got back on track, however, when she met and married a German performance artist named Martin von Haselberg in December 1984. The wedding took place in Las Vegas and was performed by an Elvis impersonator.

Midler credits von Haselberg with the turnaround in her career. He suggested that she return to comedy, her natural métier. In what turned out to be a brilliant move, she signed with the Disney Company to make a series of comedies. Positive developments continued in 1986, as she gave birth to her daughter Sophie and appeared in two smash hit movies: Down and Out in Beverly Hills (the first R-rated Disney movie) and Ruthless People. These movies established Bette Midler as a major comic actress, both nationally and internationally. They were followed in quick succession by Outrageous Fortune (1987) and Big Business (1988). In these films, though Midler’s suggestive bent could occasionally be glimpsed, it was her smirk, her grin, and her swagger, rather than her bawdiness, that appealed to a larger, more mainstream audience.

Bette, the Brand

By this time, Bette Midler was more than simply a performer; she was an institution. She released two books capturing her dissenting form of humor: A View from a Broad (1980) and a children’s verse book, The Saga of Baby Divine (1983), about a baby whose first word was “more.”

In 1989, Midler accepted a major deal with Disney’s Touchstone Pictures, becoming co-founder of her own subsidiary company, All Girl Productions. The company’s best-known films—female-centered projects like Beaches (1989), Stella (1990), and For the Boys (1992)—were popular but often critically dismissed as “chick-flicks.” Undeterred, she seemed to take the sexism of the industry on the chin.

Midler was offered the starring role in the Sister Act film franchise but turned it down, in part because of the potential for backlash against a Jewish actress seeming to mock Christianity. Instead, she returned to her roots: concertizing and regaining contact with a live audience and her legion of fans around the country. On September 4, 1993, she opened a stint at Radio City Music Hall in New York City as the first leg of a multi-city tour. She broke all records in ticket sales and logged more consecutive performances than any other single performer at Radio City.

In 1993, Midler went back to her musical-theater origins with CBS’s made-for-television movie musical Gypsy, starring as Mama Rose, a role she would reprise on Broadway from 2017 to 2019. Her 1993 performance in Hocus Pocus was underwhelming at the box office but developed into a cult classic. Similarly, she appeared in First Wives Club (1996), which became a major musical in 2009 and a television series in 2019. Once dismissed as “‘chick-flicks,” Midler’s projects emphasizing female empowerment have proven to have tremendous staying power.

Post-Millennial Midler

Bette Midler's residency show at the Colosseum at Caesar's Palace in Las Vegas.

Since 2000, Midler has continued working on films that highlight women’s perspectives. She produced Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood (2002), based on the book about a group of non-conformist girlfriends in Louisiana, and played a major role in The Stepford Wives (2004) a remake of the 1975 gender war thriller in which the town’s men replace their “liberated” wives with a group of obedient robotic look-alikes. She embodied feminist hero Bella Abzug in the Gloria Steinem biopic The Glorias (2020). And she honored one of her inspirations, Mae West, by serving as executive producer of Mae West: Die Verruchte Blond in 2021.

Midler continues to invent and reinvent herself in both old and new media. She experimented with network television with a season of the CBS sitcom Bette (2000), loosely based on her own life as the “divine” celebrity. Although the series received mixed reviews, critics recognized the versatility of her performance. And she gained accolades for her performance as Hadassah Gold on the Netflix streaming series The Politician in 2020.

Midler maintains an active social media presence. She founded the New York Restoration Project, earning her the 2002 Award for Parks from Preservation.

But Midler’s preferred medium is still concert-style live performance. In a 2000 interview with New York Times Magazine, she declared, “"I've lasted because of the audience for my stage shows,” and her specials The Showgirl Must Go On (2010) and One Night Only (2014) have affirmed that belief.

When a comic like Midler laughs at herself as well as at the foibles of her audience, she creates a connection between people and an opportunity to examine serious subjects in a funny manner. Bette Midler’s knowing smile, which rarely leaves her face, reminds her audience that a humorous perspective, on any and all subjects, offers catharsis alongside illumination and empathy.

Midler creates a persona of a woman who has a strong sense of self and a commitment to both justice and self-satisfaction. In a culture that has traditionally seen women as submissive and subservient to the men in their lives, she offers a startling alternative. Her women are bawdy, sex-positive, pushy, ambitious, and often selfish, but they are also generous in spirit, always ready to laugh, and fearless in their contact with life. With her fresh and audacious perspective, Bette Midler has become a living legacy.

Selected Records by Bette Midler

A Gift of Love (2015).

It’s The Girls (2014).

Memories of You (2010).

The Best Bette (2008).

Cool Yule (2006).

Bette (2000),

Bathhouse Betty (1998),

Bette of Roses (1995).

Experience the Divine (1993).

Some People’s Lives (1990).

Mud Will Be Flung Tonight (1985).

No Frills (1983).

Divine Madness (1980).

Thighs and Whispers (1979).

Broken Blossom (1977).

Live at Last (1977).

Songs for the New Depression (1976).

Bette Midler (1973).

The Divine Miss M (1972).

Selected Filmography

The Glorias (2020).

Coastal Elites (2020).

The Stepford Wives (2004).

Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood (2002).

Drowning Mona (2000).

The First Wives Club (1996).

Diva Las Vegas (1997).

Hocus Pocus (1993).

For the Boys (1992).

Scenes from a Mall (1991).

Stella (1990).

Beaches (1989).

Big Business (1988).

Outrageous Fortune (1987).

Ruthless People (1986).

Down and Out in Beverly Hills (1986).

Jinxed (1980).

The Rose (1979).

Baker, Robb. Bette Midler. New York: Popular Library, 1975.

Collins, Nancy. “Bette Midler: The Rolling Stone Interview.” Rolling Stone (December 9, 1982): 15–21.

Dreyfus, Claudia. “The ‘Gypsy’ in Bette.” TV Guide (December 11–17, 1993): 10–12+.

Hirschberg, Lynn. “Meta-Midler.” The New York Times Magazine (October 2000).

Mair, George. Bette: An Intimate Biography of Bette Midler. New York: Birch Lane Press, 1995.

Mullins, Mark. “The Divine Miss M.” BetteMidler.com, 2021. Accessed June 23, 2021.

Petrucelli, Alan W. “What Makes Bette Laugh?” Redbook 175 (September 1990): 76+.

Richards, Peter. “Talking with Bette Midler: ‘I’ve Had My Share of Hard Knocks.’” Redbook 171 (July 1988): 64+.

Safran, Claire. “Who Is Bette Midler?” Redbook (August 1975): 54–58.

Sessums, Kevin. “La Belle Bette.” Vanity Fair 54 (December 1991): 202–207+.

Spada, James. The Divine Bette Midler. New York: Macmillan, 1984.

Steinem, Gloria. “Our Best Bette.” Ms. 12 (December 1983): 41–46.

Weber, Bruce. “Musical Comedy Review: Experience the Divine.” NYTimes, October 18, 1993, C13+.