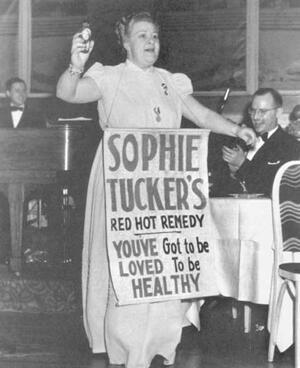

Sophie Tucker

Courtesy of the Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives.

The “Last of the Red-Hot Mamas,” Sophie Tucker defied convention with her saucy comic banter and music. Tucker moved to New York to sing, performing in cafes before breaking into vaudeville. In 1910, she first sang what became her signature song, “Some of These Days.” That same year, she was hauled offstage and tried for obscenity, but the judge threw out the case. For the next several weeks, her shows were sold out. Tucker delighted audiences throughout America and Europe in the 1920s and 1930s. In 1945, she created the Sophie Tucker Foundation, which supported various actors’ guilds, hospitals, synagogues, and Israeli youth villages. Although Tucker also performed in movies, she preferred performing on Broadway. When she died in 1966, she had two years of engagements planned.

Early Life and Family

Sophie Tucker was an international star of vaudeville, music halls, and later film, performing in both Yiddish and English in a career that spanned over fifty years. She was born Sophie Kalish in Russia as her parents were preparing to immigrate to the United States. While immigrating, her father, who feared repercussions for having deserted the Russian military, adopted the name “Abuza” for the family. When she was three months old, the family settled in Hartford, Connecticut, where they ran a successful kosher diner and rooming house that catered to many show business professionals. Tucker recalled waiting on Yiddish theater greats such as Jacob Adler, Boris and Bessie Thomashefsky, and Madame Lipsky, exclaiming, “The thrill I got when I took an order from Bertha Kalich!”

Theater people intrigued her, but her parents, wary of the vaudeville paskudnyaks [scoundrels] who traveled through their town, encouraged her to marry and settle in Hartford. In her autobiography Some of These Days, Tucker wrote that her mother believed that marriage, having babies, and helping her husband get ahead were career enough for any woman. “I couldn’t make her understand that it wasn’t a career that I was after. It was just that I wanted a life that didn’t mean spending most of it at the cookstove and the kitchen sink.”

By way of compromise, she began singing for the customers she waited on. She recalled, “I would stand up in the narrow space by the door and sing with all the drama I could put into it. At the end of the last chorus, between me and the onions there wasn’t a dry eye in the place.”

She eloped to Holyoke in 1903 with local beer cart driver Louis Tuck. Upon her return, her parents arranged a proper Orthodox wedding for the couple. They had a son, Burt (b. 1906), shortly before she asked her husband, who she asserted wasn’t working hard enough, for a separation. Soon afterward, Willie Howard of the Howard Brothers, who had admired her singing, gave her a letter of introduction to well-known composer Harold Von Tilzer. She left Hartford for New York City and changed her name to Tucker.

While Von Tilzer was not immediately impressed with her talents, Tucker soon gained employment in New York’s cafés and beer gardens such as the German Village, singing for meals, weekly pay, and “throw money” from customers. Tucker sent much of the money she earned home to her family.

Vaudeville Career

In 1907, Tucker got her first break in vaudeville, singing at Chris Brown’s amateur night. After her initial audition, she overheard Brown muttering to a colleague, “This one’s so big and ugly, the crowd out front will razz her. Better get some cork and black her up.” Despite her protestations, producers insisted that she could be successful only in blackface. Quickly booked into Joe Woods’s New England circuit, she became known as a “world renowned coon singer,” a role that she couldn’t bear to let her family know she had taken. A stroke of luck befell her when her costume trunks were lost while touring; she debuted onstage in Boston without blackface, declaring to the shocked audience: “You-all can see I’m a white girl. Well, I’ll tell you something more: I’m not Southern. I’m a Jewish girl and I just learned this Southern accent doing a blackface act for two years. And now, Mr. Leader, please play my song.”

It wasn’t long before Tucker was performing out of blackface to increasingly adulating audiences. Songs like “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” “I’m Living Alone and I Like It,” “I Ain’t Takin’ Orders from No One,” and “No Man is Ever Gonna Worry Me” were hits with female and male audiences alike, at venues such as Tony Pastor’s Palace, Reisenweber’s supper club, vaudeville houses throughout the United States, and music halls throughout Europe. In 1910, African-American composer Shelton Brooks wrote her immensely popular signature song “Some of These Days.” This, like many other songs, Tucker purchased exclusive rights to sing.

My Yiddishe Momme

In 1925, Jack Yellen penned perhaps her most famous song, sung in Yiddish and English, titled “My Yiddishe Momme.” The song was mostly played in large American cities where there were sizable Jewish audiences. Tucker explained, “Even though I loved the song and it was a sensational hit every time I sang it, I was always careful to use it only when I knew the majority of the house would understand Yiddish. However, you didn’t have to be a Jew to be moved by ‘My Yiddishe Momme.’ ‘Mother’ in any language means the same thing.”

Tucker never forgot her Jewishness, even as she performed for broader, gentile audiences. On her 1922 tour of England, Tucker was welcomed by a London audience with a sign reading “Welcome Sophie Tucker, America’s Foremost Jewish Actress.” Tucker noted, “I was prouder of that than of anything.” During the tour, Tucker got to know many Jewish actors in London, and took pleasure, at a Palladium benefit for the Lying-in Hospital, in singing “Bluebird, Where Are You,” in her words, “as a Synagogue cantorhazan would.” Tucker was immensely popular in England, amusing eager crowds with songs like “When They Start to Ration My Passion, It’s Gonna Be Tough on Me” and “I’m The Last of the Red-Hot Mamas.” Hanan Swaffer of London’s Daily Express described her as “a big fat blond genius, with a dynamic personality and amazing vitality.” Tucker’s reminiscences of several tours provide unique insights into pre- and postwar European culture.

Tucker described the terrible tension of playing for a 1932 French audience that included many Jews. Throughout her performance, they sent notes and called out requests for her to sing “My Yiddishe Momme.” Tucker was wary but finally decided to sing the song, feeling that its emotion would touch everyone. Tucker then began the song in English to a fairly receptive house. However, when she reached verse two, which is in Yiddish, anti-Semites began to boo and other audience members responded with shouts, begging for quiet. Tucker remembered, “The noise was so great I couldn’t hear my own voice, nor could I hear Teddy at the piano. I thought: in a minute there’ll be a riot. Quick as a flash I turned to Teddy and said ‘Switch!’ Before the audience knew what the hell was happening I was singing ‘Happy Days Are Here Again.’ My God, I only hoped they were!”

By contrast, the song was generally well received in Vienna. Tucker was recognized at a record store and asked to sing “My Yiddishe Momme” to an audience that seemed hungry for the images the song evokes. She reflected, “It is a commentary on Berlin in 1931 that … it was ‘My Yiddishe Momme’ that the Berlin Broadcasting Company asked for. That for the Paris mob!”

Several years after Hitler came into power, Tucker’s recordings of “My Yiddishe Momme” were ordered smashed and the sale of them banned by the Reich. The song had the power to evoke a reverence for Jewish culture and a cultural memory of more peaceful times and was thus threatening to Hitler’s regime. Shortly after the war broke out, Tucker talked with actor Elizabeth Bergner, a German in London exile, who informed Tucker, “There isn’t one of us in Germany who hasn’t this record of yours.”

Philanthropy

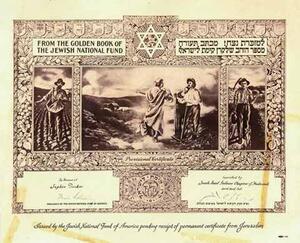

Courtesy of the Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives.

Tucker was known for her reverence of the Hebrew principle of Modestyzedakah, charity, and acts of good will toward others. In 1945, she established the Sophie Tucker Foundation, donating time, energy, and resources to an ecumenical assortment of causes. Tucker contributed to the Jewish Theatrical Guild, of which she was a life member, the Negro Actors Guild, and the Catholic Actors Guild, as well as the Will Rogers Memorial Hospital, the Motion Picture Relief Fund, synagogues, and hospitals. She supported Israel Bonds, and her foundation endowed a Sophie Tucker chair at Brandeis University in 1955. In 1959, on the first of several trips to Israel, Tucker dedicated the Sophie Tucker Youth Center at Bet Shemesh in the Judean Hills. Two years later, she sponsored another youth center at Kibbutz Be’eri in the northern Negev near Gaza. In 1962, she sponsored the Sophie Tucker Forest near the Bet Shemesh amphitheater and raised money for another forest. She also donated time and money to numerous hospitals and homes for the aged.

Tucker used her economic independence to empower herself and others, which created tensions in her personal life. Early in her career, Tucker had helped many of the prostitutes who lived in the same rooming houses as she, stashing money from their pimps, noting that, “Every one of them supported a family back home, or a child somewhere.” While on tour, she brought her band to play in houses of prostitution for women who’d taken the night off in her honor. Tucker felt that it was her economic independence that doomed her marriages to Tuck, accompanist Frank Westphal, and manager Al Lackey, all of which ended in divorce. As she explained it: “Once you start carrying your own suitcase, paying your own bills, running your own show, you’ve done something to yourself that makes you one of those women men like to call ‘a pal’ and ‘a good sport,’ the kind of woman they tell their troubles to. But you’ve cut yourself off from the orchids and the diamond bracelets, except those you buy yourself.”

Career Successes and Legacy

In her humorous raciness, Sophie Tucker could be viewed as a precursor of today’s strong female singers. Indeed, Tucker is directly evoked by Bette Midler in a portion of her performances under the persona “Soph.” Throughout her life, however, she insisted, “I’ve never sung a single song in my whole life on purpose to shock anyone. My ‘hot numbers’ are all, if you will notice, written about something that is real in the lives of millions of people.”

Despite this fact, or perhaps because of it, the self-described “King-Sized Lollabrigida” was removed from the stage in 1910 for singing “The Angle-Worm Wiggle.” The judge, however, threw out the case, and the theater held her over two weeks to sold-out houses with lines around the block.

Tucker’s performance was a complex critique of ethnic, gender, and class codes of morality. Songs like “I’m the 3-D Mama with the Big Wide Screen” and “I May Be Getting Older Every Day (But Younger Every Night)” were challenges to age, size, and gender stereotypes of women’s sexuality couched in the humor that provided an antidote to puritanism.

As vaudeville gave way to cinema, Tucker had parts in several films, including Honky Tonk (1929), Broadway Melody of 1938 (1937), Thoroughbreds Don’t Cry (1937), and Follow the Boys (1944). She was, however, critical of the movie industry, asserting that film had usurped the power of performance from performers themselves. Without a live audience, the director was “the only critic to be pleased.”

Tucker preferred performing in Broadway hits such as Cole Porter’s Leave It to Me (1938) and High Kickers (1941), which toured in London in 1948. But live theater work was harder to find in an era of sparkling celluloid faces, much to the chagrin of Tucker and others. In 1963, Sophie, a Broadway musical based on Tucker’s life, ran for only eight performances.

Tucker performed at the last show at Tony Pastor’s Palace in New York City, which marked the end of an era: “Everyone knew the theater was to be closed down, and a landmark in show business would be gone. That feeling got into the acts. The whole place, even the performers, stank of decay. I seemed to smell it. It challenged me. I was determined to give the audience the idea: why brood over yesterday? We have tomorrow. As I sang I could feel the atmosphere change. The gloom began to lift, the spirit which formerly filled the Palace and which made it famous among vaudeville houses the world over came back. That’s what an entertainer can do.”

Sophie Tucker always used her power as an entertainer both to lift spirits and provoke thought in her audiences. Describing a command performance before King George V and Queen Mary at the London Palladium in 1926, a critic wrote, “In her bespangled gown, a hairdo in layers, and wearing a long string of orchids, she made a dazzling and towering theatrical figure whose love for the audience was returned to her in waves.”

Tucker never retired, working until weeks before her death on February 9, 1966, in New York City, from a lung ailment and kidney failure at age eighty-two. Three thousand mourners attended her funeral at Emanuel Synagogue Cemetery in Wethersfield, Connecticut; striking teamsters’ union hearse drivers temporarily called off their picket in her honor. Tucker’s legacy exists in her generous contributions to charity, her influence on images of Jewish culture and women’s sexuality, and her role as an entertainer who thoughtfully interpreted the chaotic and beautiful world around her.

Sophie Tucker is featured in Making Trouble, the JWA documentary film about women comedians.

Allen, Robert C. Horrible Prettiness: Burlesque and American Culture (1991);

AJYB 68:534;

Brown, Janet. “The ‘Coon-Singer’ and ‘Coon-Song’: A Case Study of the Performer-Character Relationship.” Journal of American Culture 7, 1–2 (Spring/Summer 1984): 1–8;

Cohen, Sarah Blacher, ed. From Hester Street to Hollywood: The Jewish-American Stage and Screen (1983), and Jewish Wry: Essays on Jewish Humor (1987);

DAB 8;

EJ; “500 at Funeral of Sophie Tucker.” NYTimes, February 14, 1966;

Fricker, Karen. “Experience the Divine Bette Midler.” New York Financial Times, October 4, 1993;

Gilbert, Douglas. American Vaudeville: Its Life and Times (1963);

Green, Abel. “Two in One Week: Sophie Tucker Dies at 82, Billy Rose Succumbs at 66.” Variety (February 16, 1966);

Kaplan, Mike, ed. Variety Who’s Who in Show Business (1985);

Lifson, David S. The Yiddish Theater in America (1985);

Loy, Pamela, and Janet Brown. “Red Hot Mamas, Sex Kittens and Sweet Young Things.” International Journal of Women’s Studies 5, no. 4 (September–October 1982): 338–47;

Nachman, Gerald. “‘Hudl Mitn Shtrudl’ and Other Stage Delicacies.” San Francisco Chronicle, December 2, 1990, 17;

NAW modern;

“A Nip of Tucker.” San Francisco Chronicle, January 12, 1997;

Rogin, Michael. “Making America Home: Racial Masquerade and Ethnic Assimilation in the Transition to Talking Pictures.” Journal of American History (December 1992);

Rosenberg, Joel. “Jewish Experience on Film.” AJYB (1996);

Sandrow, Nahma. Vagabond Stars: A World History of Yiddish Theater (1977);

“The Singing Yiddishe Momma.” Israel Post, February 11, 1966, 5A;

Slide, Anthony. The Encyclopedia of Vaudeville (1994);

Sochen, June. “Fanny Brice and Sophie Tucker: Blending the Particular with the Universal.” In From Hester Street to Hollywood: The Jewish-American Stage and Screen, edited by Sarah Blacher Cohen (1983);

“Sophie Tucker Dies Here at 79 [sic].” NYTimes, February 10, 1966, 1:8;

Tucker, Sophie. Some of These Days (1945);

Unterbrink, Mary. Funny Women: American Comediennes 1860–1985 (1987);

Vicinius, Martha. “Happy Times ... If You Can Stand It: Women Entertainers During the Interwar Years in England.” Theater Journal 31 (1979): 358;

WWIAJ (1926, 1928, 1938);

WWWIA 4;

Yellen, Jack. “My Yiddishe Momme.” The Lawrence Wright Song and Dance Album (1925).