Anzia Yezierska

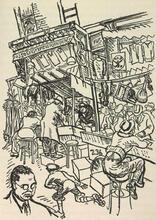

Immigrating with her family from the Russian Pale of Settlement to the United States in the early 1890s , Anzia Yezierska turned the frustrations and indignities she suffered in New York’s tenements into stories that depicted the lives of Jewish immigrants. In 1915, she published her first short story, “Free Vacation House,” about the humiliations charitable organizations perpetrate on the women they claim to help. In 1922, her collection Hungry Hearts was made into a silent film. Her first novel, Salome of the Tenements (1923), drew on the experiences of famed labor organizer, Rose Pastor Stokes. Yezierska, dubbed the "Cinderella of the Sweatshop," wrote her best-known novel, Bread Givers (1925), about an immigrant daughter struggling against her Orthodox father's rigid idea of Jewish womanhood. Her work fell into obscurity until the 1975 reissue of Bread Givers.

“My one story is hunger.” So declared the protagonist of Anzia Yezierska’s novel Children of Loneliness (1923). Having immigrated with her family from Eastern Europe, Yezierska chronicled the hunger of her generation of newly arrived Jewish Americans around the turn of the century. Her novels, short stories, and autobiographical writing vividly depict both the literal hunger of poverty and the metaphoric hunger for security, education, companionship, home, and meaning—in short, for the American dream.

Family and Personal Life

Born in the Russian-Polish village Plinsk, near Warsaw, between 1880 and 1885, the youngest of nine children, Yezierska arrived in the United States with her family in the early 1890s. The year of her birth is uncertain not only because Yezierska did not recollect the exact date but also, according to her daughter, because she perpetually reinvented her history in interviews, frequently claiming to be younger to compensate for her relatively late start as a writer. Her oldest brother Meyer preceded the family by several years. Immigration officers Americanized his name into Max Mayer, replacing his last name with a version of his first. When Anzia landed in United States at Castle Garden, the entire family was given the surname Mayer, and Anzia was renamed Harriet, later shortened to Hattie. She reclaimed the name Anzia Yezierska when she was about twenty-eight. The family settled into a cramped tenement apartment in the Lower East Side of Manhattan.

Her father, Baruch (Bernard), a talmudic scholar, engaged in full-time study of sacred books and was not gainfully employed. Her mother, Pearl, worked at menial jobs to support the family. Pressured to help support her struggling family in a cultural climate that did not legitimate the educational aspirations of girls, Yezierska attended elementary school for two years before working at a succession of domestic and factory jobs. Four of her brothers studied pharmacy, another became a high school math teacher, another an army colonel. Young Anzia clashed frequently with her father, whose poverty, religious observance, and Eastern European ways she saw as barriers to full entry into American life. Eventually, she left her parents’ apartment and moved into the Clara De Hirsch Home for Working Girls. She pursued her ambition for education with a single-minded determination. According to her daughter, Yezierska promised patrons to become a domestic science teacher to help better her people, inventing a high school education for her application to Columbia University. Continuing to support herself by menial work, Yezierska attended Columbia University’s Teachers College on scholarship from 1901 to 1905. She then taught elementary school from 1908 to 1913, with a brief leave of absence to attend the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. In 1913, she began to write fiction.

In 1910, Yezierska married Jacob Gordon, a lawyer, but she applied for an annulment the following day. She explained that while she valued his friendship, she was unprepared for the physical aspect of marriage. The following year, she married Arnold Levitas, a teacher and textbook writer, in a religious but not a civil ceremony. Their daughter, Louise Levitas (Henriksen), was born in 1912. In 1916, Yezierska moved to San Francisco with Louise and worked as social worker, the last of several flights from her marital home. Because Yezierska could not support herself and her daughter, Louise was sent to live with Levitas in New York when she was five. The couple divorced in 1916. Yezierska’s relationship with her daughter remained close but troubled. Years later, Louise Levitas described Yezierska as a vibrant, daring, and courageous person, but one whose extreme mood swings and egoism affected all her personal interactions.

Fictional Writings and Themes

Yezierska’s fiction focuses on Jewish immigrant life at the turn of the century, and she sees herself as giving voice to her people. Her work features female protagonists and explores the transition from “greenhorn” to American; the struggle against patriarchy, poverty, and restrictive Jewish practice; the striving for acceptance, independence, and prosperity in the New World; and the cultural and personal gain and loss inherent to assimilation. Yezierska pays particular attention to the hardships of poverty for women saddled with childcare and crowded conditions, and utterly financially dependent on husbands. In contrast to the ineffectual or exploitative Jewish immigrant man, her fiction frequently features a liaison with a sophisticated WASP or assimilated Jewish man who functions as the protagonist’s mentor. While Yezierska rejected her father’s Orthodox way of life and opinions, she absorbed and loved the cadences of the Bible, was interested in God and the spirit, and replaced Judaism with faith in the intellect. Her first publication, “Free Vacation House” (1915), exposes the humiliation inflicted on poor women by well-intentioned charitable organizations. Based on her sister Helena’s experience, the story’s free country house for poor mothers and their children is so rule-bound that the guests, who are forbidden to sit on the comfortable chairs in front of the house or on the porch, experience it as a prison. Social workers repeatedly ask them intimate questions in public. “The Fat of the Land” was published in Edward J. O’Brien’s Best Short Stories of 1919, which was dedicated to Yezierska. The story depicts the loneliness and anomie of an elderly immigrant Jewish woman whose successful, Americanized children support her in luxury but are ashamed of her Old World ways. Housed in an affluent neighborhood, the woman yearns for the intimacy and cultural vibrancy of the tenement world.

In 1917, Yezierska met John Dewey, who was to be the great romance of her life despite the difference in their ages—he was fifty-eight, she was in her mid-thirties. Yezierska audited his seminar in social and political thought at Columbia University. Dewey was attracted by Yezierska’s outspokenness, emotionality, and passion, she by his erudition and intellect. Dewey wrote several poems about Yezierska (in 1917–1918), while he served in her writing as the prototype of the Anglo-Saxon gentile mentor/lover. Yezierska treated the relationship fictionally in All I Could Never Be (1932). According to her daughter, Yezierska used his poems and phrases from his letters uncredited in her writing. Their relationship was fictionalized in Norma Rosen’s John and Anzia: An American Romance (1989). The breaking point in their relationship came when he made a sexual overture to her.

Yezierska was catapulted briefly to fame and fortune when Hungry Hearts (1920) caught the attention of Samuel Goldwyn, who based a 1922 silent movie on it. In 1925, Sidney Alcott directed a silent film based on Yezierska’s Salome of the Tenements. Although Goldwyn brought Yezierska to Hollywood as a screenwriter, she found her writing blocked amid wealth and removed from the culture she knew. Refusing a $100,000 contract, she returned to economic struggle in New York. In the early 1930s, she worked for the WPA Writer’s Project, cataloging trees in Central Park. Beginning in the 1950s, she wrote book reviews for the New York Times, primarily on Jewish or women’s themes whose import she universalized. Her autobiography Red Ribbon on a White Horse is considered both vibrant writing and factually unreliable. During the 1950s and 1960s, she wrote of the plight of Puerto Rican immigrants in New York, and, during the last decade of her life, she explored the theme of aging—the diminution of one’s faculties, the lack of dignity and respect, the loss of independence. Yezierska’s last published story, “Take up Your Bed and Walk,” puts forth the perspective of an elderly Jewish woman.

Literary Criticism

Critical assessment of Yezierska’s work has fluctuated since her earliest publications. Initially lauded as an authentic voice of the tenements as “Cinderella of the sweatshops,” by the 1940s, Yezierska had fallen into obscurity. Seen by the American mainstream as “too Jewish,” within the Jewish community her writing was offensive to both immigrant and Americanized Jews who felt mocked and exposed. Because of the growing interest in both ethnic and women’s writing, the 1980s saw a resurgence of appreciation for her writing. Bread Givers was reissued in 1975, followed by editions of many of her other works. Most contemporary critics approach her work sociologically rather than aesthetically, drawn by her compelling depictions of cultural and geographic displacement, the American dream and the harsh reality of immigrant life, and the struggle to acculturate.

In the main, Yezierska has been seen as aesthetically inferior to other writers of the Jewish immigrant and assimilation experience. Many critics praise the raw power of her writing but see in it no real artistry. They cite the proliferation of stock characters—the overworked mother, the ineffectual father, the intellectual gentile or assimilated male savior, the cold WASP, the rootless Americanized Jew, the condescending social worker, the passionate and intelligent young Jewish immigrant woman. Often, readers read the work as veiled autobiography, taking the voice of her protagonists as her own.

Death and Resurgent Legacy

But there has been a renewed appreciation for her oeuvre as a crafted literary work. In a biography of Yezierska, her daughter discusses her mother’s imaginative inventiveness and also contrasts the stylized “Yinglish” dialect of the fiction with her mother’s more proper, standardized English. Some contemporary readers note Yezierska’s artful use of metaphor, her ability to present multiple points of view, and the broad humor of her exaggerated types.

Anzia Yezierska died of a stroke on November 21, 1970, in Ontario, California.

Selected Works by Anzia Yezierska

All I Could Never Be (1932).

Arrogant Beggar (1927).

Bread Givers: A Struggle between a Father of the Old World and a Daughter of the New (1925. Reprinted 1975 and 1984).

Children of Loneliness (1923).

How I Found America: Collected Stories of Anzia Yezierska (1991).

Hungry Hearts (1920).

Hungry Hearts and Other Stories (1985).

The Open Cage: An Anzia Yezierska Collection (1979).

Red Ribbon on a White Horse (1950. Reprint, 1981).

Salome of the Tenements (1992).

AJYB 24:217.

BEOAJ.

EJ.

Gornick, Vivian. Introduction to How I Found America: Collected Stories of Anzia Yezierska, by Anzia Yezierska (1991).

Henriksen, Louise Levitas. Afterword to The Open Cage: An Anzia Yezierska Collection, by Anzia Yezierska (1979).

Henriksen, Louise Levitas. Introduction to Red Ribbon on a White Horse, by Anzia Yezierska (1981).

Henriksen, Louise Levitas, with Jo Ann Boydson. Anzia Yezierska: A Writer’s Life (1988).

Levin, Tobe. “Anzia Yezierska.” Jewish American Women Writers: A Bio-Bibliographical and Critical Sourcebook, edited by Ann Shapiro et al. (1994).

NAW modern.

Obituary. NYTimes, November 23, 1970, 40:2.

Rosen, Norma. John and Anzia: An American Romance (1989).

Schoen, Carol. Anzia Yezierska (1982).

Stinson, Peggy. “Anzia Yezierska.” American Women Writers 4 (1982): 480–482.

UJE.

Who’s Who in American Jewry (1926, 1928, 1938).

Who’s Who in American Jewry 7.