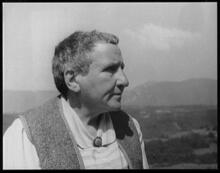

Jo Sinclair

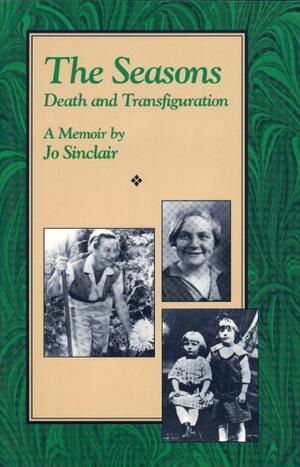

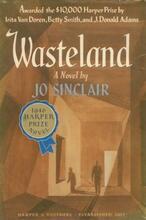

An award-winning writer who hid both her lesbian and her Jewish identity for years, Jo Sinclair used her personal experiences of prejudice to fuel her fiction. Born Ruth Seid, she began life as a factory worker before finding work through the WPA as a writer and editor. She changed her name to Jo Sinclair when she published her first story, “Noon Lynching.” Her first novel, 1946’s Harper-Prize-winning Wasteland, centered on a Jew who passes as a gentile and his sister, a closeted lesbian. In 1955 she wrote The Changelings, which showed the echoes between antisemitism and Jim-Crow-era prejudice. She continued to write novels, short stories, and a 1992 memoir, The Seasons: Death and Transfiguration, returning again and again to issues of anti-Semitism, sexual orientation, and prejudice.

Introduction

“The spirit can be the most intolerable ghetto of all,” Jo Sinclair asserts in her autobiography, The Seasons: Death and Transfiguration (1992). The statement encapsulates Sinclair’s work as a writer, as well as her life as a working-class Jewish American woman struggling with poverty, antisemitism, and sexism. Sinclair was ahead of her time in her treatment of such complex themes as Jewish and sexual identity, marginalization, and the internalization of prejudice. In her writing, which has gained increased critical attention since the 1980s, the ghetto not only connotes the physical space and limited social and economic horizons of oppressed minorities, but also serves as a metaphor for the sense of inner constraints that hamper people’s well-being.

Family and Early Life

Born Ruth Seid in Brooklyn, July 1, 1913, she was the last of the five children of Ida (Kravetsky) and Nathan Seid, Russian immigrants who had fled pogroms. When she was three, the family moved to Cleveland. Her father, a carpenter who supported his family with difficulty, never felt at ease in the United States and with the English language. His daughter felt ashamed of his Old World ways and lack of success. Although a superb student, she attended a commercial rather than an academic high school because she was expected to work to help support the family. While working in a factory, she read voraciously and began to write. In the mid-1930s, she met Helen Buchman, who was to be a lifelong friend, mentor, and patron. Buchman invited Ruth to move in with her husband and family, helped her to leave factory work for a position with the Red Cross, and encouraged her writing. She later obtained work with the WPA writers’ project.

Early Career and Adopting Her Pseudonym: Jo Sinclair

With her first published story, “Noon Lynching” (1936), Ruth Seid adopted the pseudonym Jo Sinclair, which veiled her Jewishness and introduced an element of gender ambivalence, two issues central to her life and work. The tension between her identities as Seid and Sinclair continued to trouble her throughout her lifetime. In her first novel, Wasteland (1946), which focuses on the fictional Braunowitz family and is based in part on her own family, Sinclair explores her mixed emotions regarding Jewish identity. To attain financial success and social acceptance, the protagonist, Jake Braunowitz, passes as the gentile photojournalist John Brown. At the urging of his lesbian sister, whose own struggles enable her to understand her brother, Jake sees a psychiatrist to deal with the toll of antisemitism, Jewish self-hatred, and childhood deprivation on his inner life and emotional well-being. Ironically, Sinclair herself continued to write under her ethnically neutral pseudonym. The novel won the 1946 Harper Prize for new writers, and the ten-thousand-dollar award allowed Sinclair to write full time. Sinclair produced novels, stories, radio and television scripts, and an autobiography, and also worked as a ghostwriter. Harper’s editor Ed Aswell nurtured her talent until his death in 1958.

Literary Themes and Legacy

Sinclair’s works explore the repercussions of oppression in many forms: self-denial and self-destruction, antisemitism and Jewish self-hatred, continued psychic pain due to childhood suffering and dysfunctional family relations, repression of women’s sexual energy and sexual orientation, racism and the internalization of prejudice, poverty, and other forms of marginalization. Her work looks to self-knowledge as a means of emerging from one’s internalized ghetto.

While many of Sinclair’s works explore the difficulties of being Jewish, she often uses her knowledge of antisemitism as a touchstone for examining other prejudices. Considered her best work, The Changelings (1955) compares the long history of Jewish oppression with the history of slavery and contemporary discrimination against African Americans in the United States. The novel was awarded the 1956 Jewish Book Council of America annual fiction award. Regarded as her most important script, Play the Long Moment (1951) reiterates the inner toll of discrimination by exploring the dilemma of an African-American musician torn between passing as white and acknowledging his identity and heritage.

With the burgeoning interest in ethnic and women’s writing, Sinclair’s work has gained a growing audience. Several of her volumes have been reissued in the late 1980s and 1990s by the Jewish Publication Society and by the Feminist Press.

Jo Sinclair died of cancer on July 4, 1995, in Jenkintown, Pennsylvania. She was survived by her partner, Joan Soffer.

Selected Works by Jo Sinclair

Anna Teller (1960. Reprint, 1992).

The Changelings (1955. Reprint, 1983).

The Seasons: Death and Transfiguration (1992).

Sing at My Wake (1951); Wasteland (1946. Reprint, 1987).

Bachmann, Monica. “’Someone Like Debby”: (De)Constructing a Lesbian Community of Readers.” GLQ 6:3 (2000): 377-388.

Contemporary Authors. 2d ed. Vols. 21–24, s.v. “Ruth Seid.”

Gitenstein, R. Barbara. “Jo Sinclair (Ruth Seid).” Dictionary of Literary Biography 28:295–297.

Hoffman, Warren. The Passing Game (2009)

McKay, Nellie. Afterword to The Changelings, by Jo Sinclair (1983).

Wilentz, Gay. “Jo Sinclair (Ruth Seid).” Jewish American Women Writers: A Bio-Bibliographical and Critical Sourcebook, edited by Ann Shapiro et al. (1994).