From Suffering to Action, From the Individual to the Collective

Examine inter-generational relationships among Jewish immigrants, and the role of work and workers’ youth culture in the Americanization process. Use art and writing to explore your own identity formation.

Overview

Enduring Understandings

- Articulating the circumstances of one’s own suffering is a first step in taking power to change those circumstances.

- Creating change is a social process done in community with others.

- There are many different models for creating social change (e.g, collective action, legislation).

Essential Questions

- What are various ways in which people respond to suffering and inequality?

- When does suffering/injustice become a catalyst for change?

- Why were Jewish women in particular involved in organizing the garment industry?

- What was the role of young women in organizing the garment industry?

Materials Required

- Copies for each student of the “Fact, Feeling, Idea, Question” chart

- Copies for each student or a projected display of the photos in the Photographic Impressions document study

- 8 ½ x 11” signs that read AGREE and DISAGREE

- Rope that stretches from one end of the room to the other and the list of “Walk the Line” statements

- document studies on [lightbox:15082]working conditions[/lightbox], [lightbox:15085]hours and pay[/lightbox], and [lightbox:15084]organizing[/lightbox] for three groups OR enough multiples of sets to have approximately three to six students in each group

Notes to Teacher

Teachers may want students to read the [lightbox:14850]Background Essay for the Lesson[/lightbox], but students should not encounter this information until they have finished the Walk the Line activity in Part 2 of the lesson. You may choose to incorporate the Background Essay in Lesson 4 to share more information about how the workers and those helping them transformed the injustices discussed in this lesson into better working conditions.

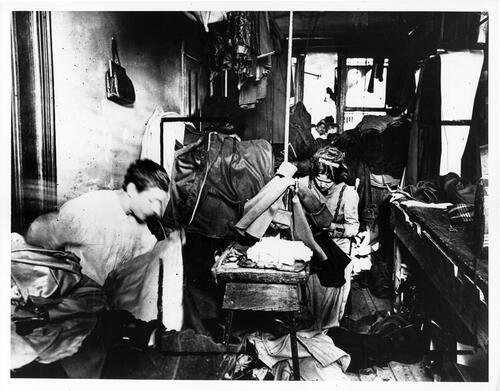

In Part 1 of the lesson, students are asked to look at two photos, one of a typical tenement “sweatshop” and the other of a factory floor, both typical garment industry workplaces at the turn of the 20th century. Students will share what they notice in each picture under the categories of “fact, feeling, idea and question” to get at both intellectual and emotional responses to the photos and to activate their thinking about what propels individuals to become part of a collective effort to make change.

In Part 2 of the lesson, students will engage in an activity called “Walk the Line.” They will hear statements that imply a range of values about labor and appropriate responses to workplace injustice, and they will place themselves on a continuum from Agree to Disagree with opportunities to explain their positions.

Part 3 of the lesson invites students to write their own, personal work manifestos after they have examined primary sources from the early 20th century period in the categories of “working conditions,” “hours and pay,” and “organizing.”

The following biographies can be used in connection to this lesson:

From Suffering to Action, From the Individual to the Collective: Introductory Essay

Introductory Essay for Living the Legacy, Labor, Lesson 2

The American labor movement was shaped by the activism of immigrant workers, and few played as prominent a role as the young Jewish women who worked in the garment industry of the early 20th century. On November 23, 1909, between 20,000 and 40,000 girls and women working in the 600 shirtwaist (blouse) factories in New York City got up from their machines in factories and sweatshops, walked out onto the city’s streets, and went on strike. In what became known as the “Uprising of the 20,000”—still the largest strike of women workers in American history—girls and women from diverse backgrounds came together to demand their rights to better working conditions, better pay, and union membership. Risking their jobs, arrest and possible deportation, rough physical treatment on the picket line at the hands of thugs hired by their bosses to teach them a lesson, and the scorn and wrath of their families, these women, nevertheless, went out on strike.

Working conditions in sweatshops and garment factories at the turn of the 20th century were brutal in the worst cases, dangerous and demeaning in the best cases. The forty hour work week did not exist at this time; garment industry laborers regularly worked fourteen hour days, six days a week, and hours could be added on Sundays during peak work seasons. There was neither a minimum wage nor overtime pay, and girls and women were regularly paid less than men were paid for doing the same jobs. Wages were deducted for late arrival, broken machinery, going to the bathroom without permission, not completing enough work in the time allotted even when the workers were forced to produce at a break-neck pace, and for other reasons beyond the control of the worker. Despite their meager wages, workers often had to provide their own machinery and supplies (such as thread).

There were no laws to protect children in the workplace. Little ones as young as six years old could be found snipping loose threads and sewing labels into finished garments. The Department of Labor was only created in 1913, and there was no Occupational Safety and Health Administration overseeing conditions in the workplace. Lighting was poor. Sanitation was poor. The heat was unbearable in the summer, and the shops and factories were cold in the winter. Exits were locked. The noise was deafening. Sexual abuse was common but rarely reported and even more rarely punished.

These were all good reasons to go out on strike, but the reasons not to strike were equally as compelling. How would the girls and women feed themselves and help to support their families if they were not working? If the strike did not succeeed, they might be fired from their jobs, and they might earn a reputation as a troublemaker and be blacklisted or prevented from working in other shops and factories. They could be arrested, labeled "radical," and even deported! If their parents or husbands disagreed with the strike, they could risk losing their families. Yet they went out on strike not just in 1909, but repeatedly in the first and second decades of the twentieth century.

For some, the lack of respect they received from the bosses was what pushed these women to go out on strike. In some shops, they were not allowed to talk to each other while they worked. They were allowed to go to the bathroom only during formal breaks. They were searched on their way out of work each day to be sure they hadn’t stolen anything. These humiliations endured day after day wore down the workers.

The Jewish girls and women connected their oppression in the workplace to the political oppression that had inspired their families to leave Europe and come to America, believing that in America they would experience greater freedom and better conditions. Some immigrants had already encountered radical political movements in Europe and were therefore already open to ideas like unionization and Socialism when they arrived in America. Some garment workers from other ethnic groups shared this background of political oppression in their countries of origin. Jewish women also carried the collective memory of the history of Jewish oppression to which they connected their own suffering. Many of the strikers believed in the possibility of change in America, and they believed they could help bring about the betterment of their conditions through labor activism.

Before the Uprising of the 20,000, Jewish women had organized boycotts and rent strikes to protest hikes in food prices and living expenses. Some of the women learned organizing skills from their involvement in the Socialist or Communist Party. Women in the garment shops began to talk with one another about their plight and about ways the union could help them. The labor unions were not interested in helping the women workers and did not take them seriously, assuming they were not invested in their work because they would soon leave the factory to marry and have families. So, without much support from the union leaders, the women began to organize themselves into “locals,” or trade and area-specific groups that would speak to shop and factory bosses and owners about working conditions for all the workers.

The garment workers were also supported by the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL), an organization founded in 1903 by middle- and upper-class women interested in helping working-class women improve their lives. The WTUL hired the young garment worker Rose Schneiderman to organize women workers. During strikes, members of the WTUL also joined the girls and women on picket lines, since the police and hired thugs were less likely to beat up a well-dressed woman, and their presence—and the media attention it drew—helped protect the working class women from violence.

The Jewish press also supported the workers during the strike. Articles in the Forward, a Socialist Yiddish paper, for example, underscored the strikers’ courage and exposed the harsh treatment they were receiving from the police.

The garment workers’ strike of 1909-1910 was not a spontaneous uprising. Rather, it grew out years of organizing women in the garment industry, as well as a series of smaller strikes throughout the summer and fall of 1909. By early November, it was unclear if and how the strikes would go forward. International Ladies Garment Workers’ Local 25 called for a general strike to shut down the entire shirtwaist industry, and on November 22, thousands of garment workers attended a meeting at Cooper Union to discuss this recommendation. After many labor leaders spoke without advocating for a general strike, 23-year-old Clara Lemlich—one of the strike leaders and a member of the Local 25 executive committee—took the stage and declared, “I am a working girl, one of those who are on strike against intolerable conditions. I am tired of listening to speakers who talk in general terms. What we are here to decide is whether we shall or shall not strike. I offer a resolution that a general strike be declared—now.” Her bold words energized the women in the crowd, and they pledged to strike.

The strike lasted 11 weeks, and while it was not a complete victory, it did win some significant demands. Most of the garment shops agreed to a 52-hour-week, at least four holidays with pay per year, no charge for tools and materials, no discrimination against union members, and the right for unions to negotiate wages with employers. By the end of the strike, 85% of all shirtwaist makers in New York had joined the ILGWU, and Local 25 had grown from 100 members to more than 10,000. Perhaps most importantly, the uprising proved that women workers could be organized into a powerful force, and it sparked five years of strikes that turned the garment industry into one of the best-organized trades in the U.S. For the young women involved in the strike, it was a powerful experience that proved their worth and mettle; many of them considered it one of the defining moments of their lives.

Unfortunately, one of the factories that did not meet the strikers’ demands for better working conditions was the Triangle Waist Co., and on Saturday, March 25, 1911, it became the site of one of the worst industrial disasters in New York’s history. Near the end of the work day, a fire broke out in the factory and spread quickly. Although the (Jewish) owners of the company had been cited several times for violation of the city's fire safety code, they had simply paid the fines and continued operating. On the day of the fire, about 500 workers were present. Most of the escape exists were locked, in order to prevent theft and walkouts and to keep out union organizers. The fire engine ladders were not tall enough to reach the top floors on which workers were trapped, and blankets and nets held by bystanders collapsed under the weight of the many workers who jumped. Others simply burned to death inside the factory. Of the 146 victims, most were Jewish immigrant women between the ages of 16 and 23.

The scale of the tragedy provoked widespread grief and outrage and galvanized the Jewish community and the progressive public into action. In the wake of public protest, the New York State Committee on Safety was established. Among its participants were forerunners of the New Deal, including Frances Perkins, Henry L. Stimson, and Henry Morgenthau, Sr. Following the committee’s recommendations, the New York State Legislature set up a Factory Investigating Commission which investigated work conditions in shops, factories, and tenement houses, and was instrumental in drafting new factory legislation. These measures limited the number of occupants on each factory floor relative to the dimensions of staircases, prescribed automatic sprinkler systems, and drafted employment laws to protect women and children at work.

The trial of the factory owners resulted in acquittal, and after collecting their insurance they soon reopened their shop at a new address and offered to pay one week’s wages to the families of the victims. In 1914 they were ordered by a judge to pay damages of seventy-five dollars to each of the twenty-three families of victims who had sued.

In the century since the Triangle Fire, it has remained a focus for labor activity. The tragedy is still being commemorated by annual demonstrations, by gatherings of women workers, and by union events, emphasizing the importance of the Occupational Safety and Health Act. Considered the worst disaster in New York City until the destruction of the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire remains one of the most vivid symbols for the American labor movement of the essential need to ensure a safe workplace environment.

Photographic Impressions

(15-20 minutes including individual work and group sharing)

- Distribute copies of the "Fact, Feeling, Idea, Question" chart to each student. You may choose to distribute copies of the photographs to individual students or project these photos one-at-a-time for students to view together.

- Ask students to look carefully at the picture. Encourage them to notice isolated parts of the picture as well as the scene as a whole. They should then write a fact, feeling, idea and question inspired by each picture in the appropriate spaces in the chart. After students have had time to do this, invite them to share their responses, which you can write on the projection below the picture or on a sheet of newsprint that you can save. It’s important to acknowledge and accept each response and not to evaluate the students' observations, except to correct obvious errors in the “fact” category. (To track common responses, we suggest you put check marks next to comments already made that come up two or more times.)

Walk the Line

- Prepare the space by moving desks and chairs to the edges of the room, placing the rope down the center of the room from the front to the back, and hanging the “AGREE” and “DISAGREE” signs on the sides of the room parallel to the rope. Ask students to line up along the line facing the front of the room. Explain that students will hear a statement read and they will then move toward the “AGREE” and “DISAGREE” signs that best represent their own values about the statement. They can move all the way to the wall, stay as close to or even on the middle line, or place themselves anywhere on the continuum between the two, extreme positions regarding that statement.

- It’s important to stress to students that they interpret the statements in whatever way makes sense to them. Answer questions by saying “whatever that means to you,” rather than interpreting the statements for the students.

- After students have placed themselves, invite up to three students to “speak their truth” about why they have positioned themselves where they are. It’s important to emphasize that they are only speaking their own truths, not having a debate or responding to what others say. Stress to students that they can change their place on the continuum if they are persuaded by what their classmates share.

-

After speakers have spoken, ask students to return to the center line and read the next statement. Repeat for as many statements as you have time.

- No one should ever endure oppression.

- You can’t fight oppression on your own.

- There are times when the only thing to do is fight.

- Only those with power or money can change society.

- Even when conditions are terrible, it can be hard to believe that things could ever change.

- Not everyone is capable of social action.

- Everyone should have the opportunity to do work that is meaningful to them.

- All work is dignified.

- Work just has to pay the bills and doesn’t have to fulfill me.

- Give the students the Introductory Essay to read individually, in small groups or together in the whole group. To help guide and focus their reading, you may want to ask them the following questions: What conditions motivated immigrant workers to protest? What challenges did they face in their attempts to unionize and to strike? What support did immigrant workers receive and from whom? Answer any factual questions that arise.

-

Break students into groups of 3-6 students to examine one set of the following documents: Working conditions, Hours and Pay, and Organizing. Have students read the documents and answer the questions that accompany each document set. Ask students to prepare a presentation to summarize the contents of their document sets for their classmates with the following information and analysis:

- A general description with one or two specific examples illustrating what the documents say about working conditions, hours and pay, and organizing in this early period.

- A description of the overarching feeling the documents convey about working conditions, hours and pay, and organizing.

- Ideas about how the speakers/writers thought about the meaning of work.

- When all the groups are ready, have each one present its document set to the whole class.

Explain that now that students have had the chance to place themselves on the continuum and speak their own truths, they will read about the historical circumstances that gave rise to women organizing in the needle trades.

Personal Work Manifestos

-

Explain the concept of a manifesto to the students: a manifesto is a statement declaring one’s principles and intentions, which can be political or religious in nature. Tell students that they will write their own, personal manifestos declaring their principles and intentions for their work lives. The manifestos should include the following:

- a “mission statement” that explains the student’s overarching belief about what work in general means to them;

- a set of principles or values to guide the student’s decisions about what work s/he is willing and not willing to do;

- a set of intentions about how the student will achieve their employment goals. What will it take for them to achieve these work goals? What obstacles might stand in their way?

Though the manifestos are meant to be personal, encourage the students to think about how their individual work goals relate to the larger community—in what ways might they be part of a collective? How does their work relate to the work of others? Who might they turn to if they needed to make change in their work conditions?

View some example manifestos.

Photographic Impressions

Fact, Feeling, Idea, Question

Directions

Look carefully at the first picture. Ask yourself: What is going on? Take note of the different parts of the picture, the background and the foreground. Notice the different people and objects. Look at it up close and from farther away to see if you notice different things.

Sweatshop circa 1900

ACWA Archives, Kheel Center, Cornell University

Directions

Next, fill out the chart “Fact, Feeling, Idea, Question.”

Directions

Now look at the second picture. Again, notice the different people, the setting, and what relationships or interactions may be taking place. Fill out the second space in the chart.

Small Garment Factory circa 1910

Courtesy of ILGWU Archives, Kheel Center, Cornell University

Directions

Finally, look at the third picture. What do you notice about the people? The place where the photograph takes place? What might these people be thinking? Complete the chart by filling in “Fact, Feeling, Idea, Question” for the last picture.

Garment Factory circa 1910

Courtesy of ILGWU Archives, Kheel Center, Cornell University

Directions

Now that you have finished, wait for the rest of the students to be done, and discuss your reactions with the class.

Working Conditions

Excerpt from Pauline Newman’s unpublished memoir, in which she describes the monotony and hardships of garment work.

… The job I found next was to sew buttons on shirtwaists. The shop was located in an old walk-up building on Jackson Street, near the East River and facing what was then called Jackson Street park. From where I sat I could see children playing there, hear them singing “all around the mulberry bush.” As I mentioned before, it was summer and the air in the shop [was] stuffy and hot. Often I longed to join the youngsters in the park and to breathe the cool fresh air. After all, I was not much older than they were! At the end of my first day’s work I was handed a slip of paper showing that I had earned thirty-five cents! I considered myself rich!...

One day a relative of mine who was employed by the now infamous Triangle Shirt Waist co., the largest manufacturers of shirt waists in New York City, got me a job with that firm. The day I left the Jackson Street shop the foreman told me that I was very lucky to have gotten a job with that concern because there is work all year.

As I said before, the job was not strenuous. It was tedious. Since our day began early we were often hungry for sleep. I remember a song we used to sing which began with “I would rather sleep than eat.” This song was very popular at that time. But there were conditions of work which in our ignorance we so patiently tolerated such as the deductions from our meager wages if and when you were five minutes late – so often due to transportation delays; there was the constant watching you, lest you pause for a moment from your work; (rubber heels had just come into use and you rarely heard the foreman or the employer sneak up behind you, watching.) You were watched when you went to the lavatory and if in the opinion of the forelady you stayed a minute or two longer than she thought you should have you were threatened with being fired; there was the searching of your purse or any package you happen to have lest you may have taken a bit of lace or thread. The deductions for being late was stricktly [sic] enforced because deductions even for a few minutes from several hundred people must have meant quite a sum of money. And since it was money the Triangle Waist Co. employers were after this was an easy way to get it. That these deductions meant less food for the worker’s children bothered the employers not at all. If they had a conscience it apparently did not function in that direction. As I look back to those years of actual slavery I am quite certain that the conditions under which we worked and which existed in the factory of the Triangle Waist Co. were the acme of exploitation perpetrated by humans upon defenceless [sic] men, women and children – a sort of punishment for being poor and docile…

Despite these inhuman working conditions the workers – including myself – continued to work for this firm. What good would it do to change jobs since similar conditions existed in all garment factories of that era? There were other reasons why we did not change jobs – call them psychological, if you will. One gets used to a place even if it is only a work shop. One gets to know the people you work with. You are no longer a stranger and alone. You have a feeling of belonging which helps to make life in a factory a bit easier to endure. Very often friendships are formed and a common understanding established. These, among other factors made us stay put, as it were…

When I got home I sat down and wrote:

“In despair I ask – ‘dear God will it ever be different?’ And on my way home from work I see again those lonely men and women with hopeless faces, tired eyes; harassed by want and worry – I again ask ‘will it ever be different?’”

The Factory Girl's Danger

On Friday evening, March 24, two young sisters walked down the stairways from the ninth floor where they were employed and joined the horde of workers that nightly surges homeward into New York's East Side. Since eight o'clock they had been bending over shirt-waists of silk and lace, tensely guiding the valuable fabrics through their swift machines, with hundreds of power driven machines whirring madly about them; and now the two were very weary, and were filled with that despondency which comes after a day of exhausting routine, when the next day, and the next week, and the next year, hold promise of nothing better than just this same monotonous strain.

They were moodily silent when they sat down to supper in the three-room tenement apartment where they boarded. At last their landlady (who told me of that evening's talk, indelibly stamped upon her mind) inquired if they were feeling unwell.

"Oh, I wish we could quit the shop!" burst out Becky, the younger sister, aged eighteen. "That place is going to kill us some day."

It's worse than it was before the strike, a year ago," bitterly said Gussie, the older. "The boss squeezes us at every point, and drives us to the limit. He carries us up in elevators of mornings, so we won't lose a second in getting started; but at night, when we're tired and the boss has got all out of us he wants for the day, he makes us walk down. At eight o'clock he shuts the doors, so that if you come even a minute late you can't get in till noon, and so lose half a day; he does that to make sure that every person gets there on time or ahead of time. He fines us for every little thing; he always holds back a week's wages to be sure that he can be able to collect for damages he says we do, and to keep us from leaving; and every evening he searches our pocketbooks and bags to see that we don't carry any goods or trimmings away. Oh, you would think you are in Russia again!"

That's all true; but what worries me more is a fire," said Becky, with a shiver. "Since that factory in Newark where so many girls where burnt up there's not a day when I don't wonder what would happen if a fire started in our shop."

"But you could get out, couldn't you?" asked the landlady.

"Some of us might," grimly said Gussie, who had been through last year's strike, and still felt the bitterness of that long struggle. "What chance would we have? Between me and the doors there are solid rows on rows of machines. Think of all of us hundreds of girls trying to get across those machines to the doors. You see what chance we have!"

"Girls, you must leave that place!" cried the landlady. "You must find new jobs!"

"How am I going to find a new job?" demanded Gussie. "If I take a day off to hunt a job, the boss will fire me. I might be out of work for weeks, and I can't afford that. Besides, if I found a new job, it wouldn't be any better. All the bosses drive you the same way, and our shop is as safe as any, and safer than some. No, we've got to keep on working, no matter what the danger. It's work or starve. That's all there is to it."

The next morning the two sisters joined their six hundred fellow-workers at the close-packed, swift machines. All day they bent over endless shirt-waists. Evening came; a few more minutes and they would have been dismissed, when there was a sudden frantic cry of "Fire!" - and what happened next all the country knows, for it was in the Triangle Shirt-Waist Factory that Becky and Gussie Kappelman worked. The fire flashed through the eighth, ninth, and tenth floors of the great building like a train of powder; girls were driven to leap wildly, their clothes afire, from the lofty windows; and in a few brief moments after the first cry one hundred and forty-three workers, the vast majority young girls, were charred bodies heaped up behind doors they had vainly tried to beat down, or were unrecognizable pulp upon the street far below.

And as for Gussie and Becky, who had gone to work that fatal day knowing their danger, as all the workers knew it, but helpless in their necessity what of them? Gussie was one of those who met a horrible death. Becky, in some way unknown to herself, was carried down an elevator, and to-day lies in a hospital, an arm and a leg broken and her head badly bruised. Frequently the young girl calls for her older sister, but her condition is too precarious for her to stand the shock of the awful truth, and the nurses have told her that Gussie is injured in another hospital. And so Becky lies in the white cot waiting until her wounds and Gussie's shall have healed and they can again be together.

Excerpt from "Out of the Shadow" by Rose Cohen

“There was one man in the shop, the designer and sample maker of the cloaks, to whom the other men looked up…Whenever he was not busy he would come and amuse himself by telling obscene stories and jokes. He did not like me, for when I had first come I had managed to gather the courage to ask the boss whether we girls could not sit at a separate table. The news of this unusual request soon spread and I began to be looked at as one who put on airs…He talked of the most intimate relations of married people in a way that made even the men exclaim and curse him while they laughed. We girls as usual sat with our heads hanging.”

Cohen, Rose. Out of the Shadow: A Russian Jewish Girlhood on the Lower East Side. New York: George H. Doran Company, 1918, p.274. Full text available online.

Preliminary Report of the Factory Investigating Commission

Our system of industrial production has taken gigantic strides in the progressive utilization of natural resources and the exploitation of the inventive genius of the human mind, but has at the same time shown a terrible waste of human resources, of human health and life.

It is because of this neglect of the human factor that we have found so many preventable defects in industrial establishments, such a large number of workshops with inadequate light and illumination, with no provision for ventilation, without proper care for cleanliness, and without ordinary indispensable comforts such as washing facilities, water supply, toilet accommodations, dressing-rooms, etc. It is because of utter neglect on the part of many employers that so many dangerous elements are found in certain trades. These elements are not always necessary for the successful pursuit of the trade, and their elimination would mean a great improvement in the health of the workers, and would stop much of the misery caused by the occupational diseases incident to certain industries.

Discussion Questions

- What working conditions do the speakers/writers of these documents describe as being unjust? What conditions do you think were unjust but the speakers/writers don’t describe as such?

- What reasons do the speakers/writers give for putting up with the conditions about which they complain?

- How do the working conditions they describe make the speakers/writers feel about themselves and about their lives?

- How did the injustice they experience lead to change in working conditions?

Organizing

Excerpt from Pauline Newman’s unpublished memoir, in which she recalls the beginning of the 1909 garment workers’ strike

Despite these inhuman working conditions the workers – including myself – continued to work for this firm. What good would it do to change jobs since similar conditions existed in all garment factories of that era? There were other reasons why we did not change jobs – call them psychological, if you will. One gets used to a place even if it is only a work shop. One gets to know the people you work with. You are no longer a stranger and alone. You have a feeling of belonging which helps to make life in a factory a bit easier to endure. Very often friendships are formed and a common understanding established. These, among other factors made us stay put, as it were…

During the early part of November an unknown (to me) source provided the money for calling a mass meeting of the shirt waist makers in the historic Cooper Union hall. The place was packed. There were many prominent speakers among them the President of the American Federation of Labor – Samuel Gompers, and Mary Dreier of the Women’s Trade Union League. The workers were urged to join the union and put an end to their exploitation. In the midst of all the admirable speeches a girl worker – Clara Lemlich by name, got up and shouted “Mr. Chairman, we are tired of listening to speeches. I move that we go on strike now!” and other workers got up and said “We are starving while we work, we may as well starve while we strike.” Pendimonium [sic] broke lose [sic] in the hall. Shouts, cheering, applause, confusion and shouting of “strike, strike” was heard not only in the hall but outside as well. There were many workers who could not get into the hall. There were no loud-speakers in those days, but word was carried to them and they joined in the cry for a strike. As one of them said, “Why not, we have nothing to lose and we may have something to gain.”

It was the 22nd of November when the strike was called. I remember the day – a grey sky, chilly winds and the winter just around the corner. However, neither the cold wind nor the cloudy sky prevented the strikers from cheering their own courage and daring as they left shop after shop to join their co-workers on the streets of New York. Despair turned to hope – marching from virtual slavery to the promise of freedom and decency. Five thousand, ten thousand, twenty thousand filled every hall available. That day was indeed a red letter day for the strikers and for the union. On this day young women laid the foundation for the powerful, constructive and influential union in the American Labor Movement, the ILGWU. As women they never did get the credit for what they contributed to the building of the present structure known all over the world as the most progressive labor organization in existence. That, however, did not prevent them from proving (and in those days to prove was essential) that women without experience can and did rise from their slumber to fight for a happier existence with determination and without fear.

During the weeks and months of the strike most of them would go hungry. Many of them would find themselves without a roof above their heads. All of them would be cold and lonely. But all of them also knew and understood that their own courage would warm them; that hope for a better life would feed them; that fortitude would shelter them; that their fight for a better life would lift their spirit. They were ready and willing to endure hardship of any kind until victory was in sight. And fight they did.

Rose Schneiderman’s Women’s Trade Union League Report

I commenced my work as East Side organizer on the 1st of April, 1908, and for a period of four months felt that I had attempted one of the most difficult industrial problems, in a most critical time of the struggle of the working class. For a time I felt that all was hopeless and dark, and that it were better for me to return to the factory. It is a very difficult thing to tell people who are starved for the lack of work, “Organize now as you never did before and endeavor by the might of your numbers to prevent industrial panics in the future!” The answer comes, “I am hungry! Give me work, and then we will speak of what is to be done.” I therefore began to visit East Side unions which had women in them and simply stated that the Women’s Trade Union League had put an organizer into the field and that she was always ready to do all in her power to help to bring the girls of the trade into the organization; also, that the League was prepared to open English classes, where trades-unionism would be taught together with the English language.

The White Goods Union

I visited the White Goods Union which, twenty-eight months ago had a membership of three hundred, and found that all that they were left with, were the officers. We conferred together, and they asked whether the League would assist them financially in holding mass-meetings. I said that it would, and we decided that a concert be arranged. This was a failure, as very few of the girls attended. We then decided to have a May Dance for the East Side women unionists, and invitations were distributed among the unions…Thought the attendance was not as large as we anticipated, good work was done, as those who came listened to the gospel of trade unionism from the lips of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, John Dych and Jacob Pankin, and when the girls left, they were much wiser as to woman’s place in industry….

The Dress Makers’ Strike

In the beginning of November last, the League was called to assist the dress makers of a Fifth Avenue shop, who were striking to resist a change of system from “piece work” to “week work.” The girls were alone, inexperienced and without any reserve funds. Brother Pine of the United Hebrew Trades, to whom they applied for assistance, was not in the position to give them all the aid they needed…The first thing we did, was to organize the girls into a Union. We found that the girls of other factories understood that the fight was theirs as well, as a principle was involved which would have a vital effect upon them. They, therefore, responded to an appeal for assistance by making collections among themselves…Little by little the girls found employment at other shops and the strike gradually dwindled away. At present, we have a Dressmakers and Costumers’ Local #60 of the Garment workers, of which I have the honor of being president, and there is good promise for the development of a big, strong organization in the near future….

In conclusion, I would say that the organization of women with its many difficulties – the different nationalities and the passive toleration of many wrongs – is a great problem, which requires constant vigilance and attention besides personal labor of everyone interested in the movement, for its solution. I would also suggest that perhaps, we, who are trying our best to solve this problem, have not considered seriously enough the joyless life of the working woman, and that, perhaps, wee have not done all that is necessary to make the labor organization a social as well as an economic attraction. We have insisted on the business-side of labor organization, forgetting the while, that women are not as yet wholly business-like, thank goodness! Let us idealize more the trade union movement, show that it is the way towards the emancipation of the worker, and with that aim in view and a great deal of hard, earnest, perservering [sic] work, the victory will be ours. Respectfully submitted, Rose Schneiderman

Ladies Tailors Strikers, February 1909

Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress.

Sarah Rozner discusses striking and making a living

The three of us were striking, my brother Dave, my sister Fanny, and me. Fanny was 15 and she’d be on the corner selling papers for the strike. She had a good time; she was young and gay and singing. My brother’s first wife was my girlfriend, and we had one good skirt between us. If she went on the picket line, we raised the hem, because she was much shorter than I; when I went on the picket line, I’d let the hem down. That’s the way we lived.

Fanny got a couple of pennies from selling the socialist papers, enough for a couple of loaves of bread. But we were hungry. They didn’t feed us in the strike hall. Sedosky, a Jewish writer, had a restaurant where for 15 cents they used to get some strike tickets for a full meal. But that was only for single men. They finally did give us some tickets to a storehouse. It was on Maxwell or Jefferson Street and was a storehouse for strikers who had family responsibilities. They had food of various sorts: bread, herring, beans, rice. None of the family wanted to go there, so I went alone. I brought home the “bacon.”

Discussion Questions

- What were the conditions that caused workers to organize?

- Why did the speakers/writers decide to join a union? Give specific examples from the documents.

- How do the writers/speakers describe the feeling of working collectively with others to demand changes in their working conditions?

- Look at the picture. What do you see going on in the picture? Based on the accounts given in this document study, what conclusions can you draw about these women?

- What kinds of activities did the labor organizers engage in to get women workers to join unions? What kinds of arguments did they make?

Hours and Pay

Rose Schneiderman describes her experience as a department store errand girl

I got a job as an errand girl [at Hearn’s Department Store] and was stationed on the first floor where tables were laden with sales merchandise…My weekly salary was $2.16 for a sixty-four-hour week. The sixteen cents was supposed to cover the weekly cost of laundering the over-all apron I was required to wear on the job. It was navy blue muslin with white polka-dots and it was most unattractive, but I saved the sixteen cents by laundering it myself…

After working at Ridley’s for three years, my salary was all of $2.75 a week!

Ann, who worked in a factory making artificial flowers and feathers, was earning much more than I, and more than Martha Apple [who had worked there for 14 years], who still made only $7.00 a week.

Rose Schneiderman describes her work as a lining maker

Like all lining-makers, I had to furnish my own sewing machine. One could be bought from Singer on the installment plan for one hundred dollars. But since Mother had been able to save a little money, how I’ll never know, we bought a Wilcox and Gibbs one-thread machine for thirty dollars cash. I also had to furnish the thread I used. And not just one color either. You had to have several colors handy to mach the colors of the lining. The cost ran up to at least fifty cents a month.

I learned to use the machine in three or four weeks and after a trial period with Cornelia, I was on my own. The first week on the job I earned six dollars, more than twice as much as I had earned at Ridley’s. However, Mother was far from happy. She thought working in a store much more genteel than working in a factory. But we needed that extra money.

Pauline Newman describes working at the Triangle

… The job I found next was to sew buttons on shirtwaists. The shop was located in an old walk-up building on Jackson Street, near the East River and facing what was then called Jackson Street park… At the end of my first day’s work I was handed a slip of paper showing that I had earned thirty-five cents! I considered myself rich!

The day’s work was supposed to end at six in the afternoon. But, during most of the year we youngsters worked overtime until 9 p.m. every night except Fridays and Saturdays. No, we did not get additional pay for overtime. At this point it is worth recording the generocity [sic] of the Triangle Waist Co. by giving us a piece of apple pie for supper instead of additional pay! Working men and women of today who receive time and one half and at times double time for overtime will find it difficult to understand and to believe that the workers of those days were evidently willing to accept such conditions of labor without protest. However, the answer is quite simple – we were not organized and we knew that individual protest amounted to the loss of one’s job. No one in those days could afford the luxury of changing jobs – there was no unemployment insurance, there was nothing better than to look for another job which will not be better than the one we had. Therefore, we were, due to our ignorance and poverty, helpless against the power of the exploiters.

As you will note, the days were long and the wages were low – my starting wage was just one dollar and a half a week – a long week – consisting more often than not, of seven days. Especially this was true during the season, which in those days were longer than they are now. I will never forget the sign which on Saturday afternoons was posted on the wall near the elevator stating – “If you don’t come in on Sunday you need not come in on Monday!” What choice did we have except to look for another job on Monday morning. We did not relish the thought of walking the factory district in search of another job. And would we find a better one? We did not think so. So we came in to work on Sundays, tho we did not like it. As a matter of fact we looked forward to the one day on which we could sleep a little longer, go to the park and get to see one’s friends and relatives. It was a bitter disappointment.

Rose Cohen recalls her first day on the job in a piecework shop

All day I took my finished work and laid it on the boss’s table. He would glance at the clock and give me other work. Before the day was over I knew that this was a “piece work shop,” that there were four machines and sixteen people were working…

Seven o’clock came and everyone worked on. [She had arrived at the shop at 7:00 in the morning.] I wanted to rise as father had told me to do and go home. But I had not the courage to stand up alone. I kept putting off going from minute to minute. My neck felt stiff and my back ached. I wished there were a back to my chair so that I could rest against it a little. When the people began to go home it seemed to me that it had been night a long time.

The next morning when I came into the shop at seven o’clock, I saw at once that all the people were there and working steadily as if they had been at work a long while. I had just time to put away my coat and go over to the table, when the boss shouted gruffly, “Look here, girl, if you want to work here you better come in early. No office hours in my shop.”

From this hour a hard life began for me. He refused to employ me except by the week. He paid me three dollars and for this he hurried me from early until late. He gave me only two coats at a time to do. When I took them over and as he handed me the work he would say quickly and sharply, “Hurry!”…Late at night when the people would stand up and begin to fold their work away and I too would rise, feeling stiff in every limb and thinking with dread of our cold empty little room and the uncooked rice, he would come over with still another coat.

“I need it the first thing in the morning,” he would give as an excuse. I understood that he was taking advantage of me because I was a child.

[Cohen’s father] never came home before eleven and he left at five in the morning. He said to me now, “Work a little longer until you have more experience; then you can be independent.”

“But if I did piece work [getting paid by finished piece rather than by the week], father, I would not have to hurry so. And I could go home earlier when the other people go.”

Father explained further, “It pays him better to employ you by the week. Don’t you see if you did piece work he would have to pay you as much as he pays a woman piece worker? But this way he gets almost as much work out of you for half the amount a woman is paid.”

I myself did not want to leave the shop for fear of losing a day or even more perhaps in finding other work. To lose half a dollar meant that it would take so much longer before mother and the children would come.

Discussion Questions

- Do the speakers/writers believe they are paid fairly for the work they are doing? Provide quotations to back up your response.

- Do the speakers/writers believe the hours they worked were reasonable? Provide quotations to back up your response.

- What kinds of trade-offs do the workers talk about making in choosing to work where they did? What did they lose? What did they gain?

- Why did these young people have to work?

Example Work Manifestos by Etta King, 2012

Open this section in a new tab to print

I had so much fun reviewing the Lessons in Unit 1 and assembling an adult education class for my shul "Ethics of Work" as part of my ongoing "Jewish Ethics" series. I created the list below of what I used for the class--but with a full class of highly-engaged religious school parents and empty nesters, I could hardly get a word in! All loved the primary documents and the Traditional Jewish Sources. It inspired much spirited debate and listening. Thanks to JWA for all you do!!

Discussed facts in Introductory Essays for Lessons 1 and 2. Photo regarding Garment workers eating together before union-sponsored class Photo regarding Social Psychology Lecture outside Unity House Discussed analogy to 2012 Bangladesh factory fire, comparing to the Triangle Shirt Waist Co. as discussed in comments to Lesson 2 (Thanks to comment-er, and to Etta for cite to NYTimes for facts and photos!) Traditional Jewish Sources from Lesson 1 Deuteronomy, Pirkei Avot Bread and Roses Poem (which makes a wonderful complement to Pirkei Avot passage) Excerpt from the Living Wage Teshuvah by Rabbi Jill Jacobs in Unit 1 Lesson 8

I loved this lesson, and used the Triangle Waist Factory info to connect to the recent fire in Bangladesh, where workers died in a factory there. Found that to be a good way to bring students into the modern era with timeless messages.

In reply to <p>I loved this lesson, and by Emilia Diamant

Thanks for your comment, Emilia. For educators interested in bringing these issues into current events, the fire in Bangladesh is a very relevant tie-in. The New York Times has several articles on its site (I've included one link below that has links to related articles).

If you are an educator working with adults or older teens, many of the pictures from the NYT site about the fire in Bangladesh are very reminiscent of the photos of the Triangle fire and its aftermath. Could be an interesting entry point for discussion, though probably not appropriate for all audiences.

Bangladesh Factory Fire Caused by Gross Negligence

Thanks again for posting! -Etta King, Education Program Manager

In reply to <p>Thanks for your comment, by EKing

We have also covered this on our blog. This post from April 2013 has additional information about the current proposals for addressing this problem in the comments section. http://jwa.org/blog/tragedy-in...

In reply to <p>I loved this lesson, and by Emilia Diamant

Thanks , I've recently been looking for info approximately this topic for a while

and yours is the greatest I have discovered till now.

But, what about the conclusion? Are you sure concerning the source?