Socialism in the United States

Disproportionate numbers of Jewish immigrant women in America were associated with socialism in the first decades of the twentieth century. Their ideological commitment was expressed mainly in activism in left-leaning garment workers' unions. Their radicalism grew out of the same sources as male radicalism, including changes experienced in late 19th century Europe and America, including proletarianization and secularization, but Jewish working women's radical consciousness and collective action emerged in the face of additional and different obstacles. Lacking marketable skills, women were more economically vulnerable. There was, too, the indifference of men, and hostility from organized labor. The women also confronted competing claims of feminism and socialism and significant cultural expectations, Jewish and American, about their proper place. By the 1930s, however, Jewish working women had made important, long-term contributions to the labor movement and social welfare.

Disproportionate numbers of Jewish immigrant women in America were associated with socialism in the first decades of the twentieth century. Their ideological commitment was expressed in activism in left-leaning garment workers' unions, the Socialist Party, and socialism generally. Their radicalism appears to have grown out of the same sources as male radicalism – the changes experienced by the Jewish community in late nineteenth-century Europe and America, including proletarianization and the secularization of Jewish religious values. But Jewish working women's radical consciousness and their militant collective action in America emerged in the face of extraordinary obstacles.

The women often lacked marketable skills and were more economically vulnerable than men. Moreover, in their attempts to organize, they came up against the cyclical nature of household, as well as wage, labor. The women also struggled against the indifference of men, and even against outright hostility from organized labor, including male-dominated socialist unions, and from the male-led Socialist Party. In addition they confronted competing claims of feminism and socialism, as well as significant cultural expectations, Jewish and American, about the "proper" place and role of women. By the 1930s, although they had not achieved equality in the unions or the party, and although they continued to steer an uneasy course between class solidarity and feminist reform, Jewish working women had made a significant, long-term contribution to the labor movement and social welfare.

The European Experience

Most of the Jewish women who went on to become socialists had had little or no experience with actual factory or shop work. Many of them came to America when they were young teenagers, but most were aware of the growing numbers of Jewish women workers in the old countries, including their mothers. The Russian census of 1897 indicated that 15 percent of Jewish artisans were female and more than 20 percent of Jewish women were employed outside the home.

Although much of the work was drudgery and necessary for economic survival, employment expanded the environment of many females beyond the narrow domesticity of the (Yiddish) Small-town Jewish community in Eastern Europe.shtetl.

The women were also aware of growing educational opportunities. Despite the official preference in traditional Jewish families for the male child, many of the women who were socialists in America had, as girls, received some formal education in Eastern Europe. Increasing aspirations, stimulated in part by new opportunities, moved many Jews, especially previously hemmed-in girls and young women, to demand even more change.

Significant numbers of women took part in the Jewish revolutionary movements as these developed in Eastern Europe. Young, unmarried women appear to have constituted one-third of the Bund's membership from its beginning in 1897, and they held the organization together after the mass arrests of 1898. In the 1900s, increasing numbers of Jewish women were arrested for political activities. Several who were socialists and militant trade unionists in the United States had been radicalized, or at the very least, had become acquainted with revolutionary turmoil, during this period in Eastern Europe. These included Social Democrat Rose Pesotta, Bundist Flora Weiss, Socialist-Territorialist Marsha Farbman, Social Revolutionary Fannia Cohn, and militant labor activists Rose Schneiderman, Clara Lemlich, and Pauline Newman. When hopes for revolution in Russia ebbed or pogroms intensified, desire for refuge in America, and for an opportunity to fulfill raised aspirations, increased for many, whether or not they were already activists.

American Dreams

The aspirations of young Jewish women were reflected in the large numbers who pursued education after their arrival in the United States while working ten or more hours a day in the garment shops. Going to school at night and working for wages, these women could dream of self-sufficiency, even though a good part of their wages went to supplement family income or to support brothers in higher education. Jobs in the garment industry, however, were oppressive and demoralizing, and threatened the women's dreams. Bosses often took advantage of girls, most of whom they assumed were timid and “green.” Females were paid less for the same work, timed when they left to go to the toilet, and subjected to speedups. Sexual harassment was also a serious problem. It is reported in a significant number of memoirs, and once women were organized and union grievance procedures established, charges of sexual abuse were prevalent.

These conditions, and the presence of a cadre of budding radical Jewish women and men in America, led to a flurry of socialist and union organizing activity by the late 1880s. For a long time, socialism and unionism could not sustain coherent movements among immigrant workers. Socialism was, however, a vital theme in Jewish immigrant life almost from the beginning. As early as 1890, twenty-seven unions and socialist organizations from New York, with a membership close to fourteen thousand, were represented at a United Hebrew Trades conference. It was possible for an American journalist to believe by 1909 that “most of the Jews of the East Side though not all acknowledged socialists are strongly inclined toward socialism.”

Clara Lemlich and the Uprising of the 20,000

The journalist exaggerated. But in that same year, the shirtwaistmakers' strike, known as the Uprising of the 20,000, set off a decade of labor unrest in the garment trades, which brought ever-larger numbers into the battle for economic and social justice. On November 22, 1909, Clara Lemlich (Shavelson), a feisty and courageous working girl, daughter of an Orthodox Jewish scholar, who became a brilliant orator and agitator, met with tumultuous enthusiasm when she proposed the general strike. At least twenty thousand shirtwaistmakers, mostly Jewish girls and women between the ages of sixteen and twenty-five, joined the "uprising." Only the tiniest minority of them were members of the socialist International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU). In the year following the strike, Local 25 alone counted over ten thousand members. The largest strike by women in the United States to that time, the shirtwaistmakers' rebellion stimulated subsequent struggles and victories that led to the formation of stable and relatively powerful socialist unions.

Clara Lemlich was no stranger to militancy. From the time she was ten in the Ukraine, she had been reading Turgenev, Gorky, and revolutionary literature. Like many others, she fled the Kishinev pogrom of 1903. Within a week of her arrival in the United States, fifteen-year-old Clara was at work as a skilled and relatively well-paid draper. She was saving money for medical school when in 1906, as she put it, “some of us girls who were more class-conscious ... organized the first local.” Lemlich was one of seven young women and six men who founded Local 25 of the ILGWU. She participated thereafter in a number of strikes that led up to the major conflict of 1909, by which time she had become well known in activist trade unionist and Socialist Party circles. Clara Lemlich was part of a growing and important cadre. In many shops there were women like her who influenced significant numbers of others through persistent discussion, invoking a sense of sisterhood, and example.

The Triangle Fire and the Growth of Labor Unions

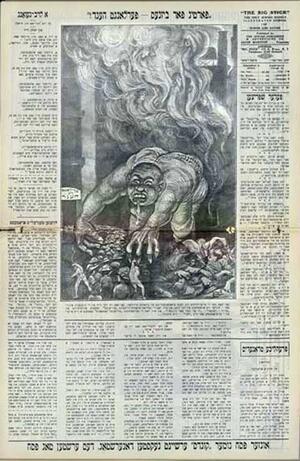

Perhaps no single development galvanized Jewish immigrants for militant unionism and socialism more than the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire of 1911, which killed 146 workers. The Yiddish press repeated the harrowing details of locked doors, inadequate fire escapes, and burning bodies. And as several women reported, the word “socialism” kept recurring in speeches memorializing the Triangle fire. The fire and its aftermath left a deep impression. Even those who had been radicalized in the Old Country credit the Triangle fire with reinforcing their activist commitments. Fannia Cohn, who in Russia “imbibed and participated in the revolutionary spirit,” said “it was the Triangle fire that decided my life's course.” After a stirring mass funeral for the victims of the fire, organizers and activists, like Rose Schneiderman, hammered home the message: “I know from ... experience it is up to the working people to save themselves. The only way they can ... is by a strong working-class movement.”

Between 1909 and 1920, numerous strikes and organizational campaigns changed a largely unorganized industry into a union stronghold. Jewish immigrant women played a major role in this development, and in the process they transformed their shops and themselves. Not all, but a measurably disproportionate number were politicized. The strikes had linked workplace complaints with larger communal concerns for social justice, and reflected a complex mixture of personal goals and collective consciousness. Flora Weiss, for example, wanted to learn dressmaking “to earn a lot of money.” But she also “wanted to organize the workers around me ... to do something for mankind.”

By 1920, the ILGWU had become the sixth largest union in the American Federation of Labor. Of the 102,000 dues-paying members, two-thirds were women. Women also constituted one third of the membership of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA). In 1920, only 15 percent of women in manufacturing industries overall were unionized, while more than 45 percent of female laborers in the garment industry were in unions. This exceptional development was the result of a combination of immediate shop-floor abuses, women's evolving concerns about their dignity as females and workers, and the influence of a highly visible and vocal group of Jewish socialists and other leftist radicals.

The Response of the Jewish Community

In addition, the Jewish immigrant community was generally sympathetic to labor organization. The Jewish socialists, most of whom were deeply rooted in yiddishkeit, and in Jewish ethical and prophetic tradition, came to embody a socialism partly derived from Jewish culture and a secular form of tikkun olam – an injunction to repair or improve the Earth. Many were dedicated not only to class struggle and the establishment of the “Cooperative Commonwealth,” but also to the protection and preservation of Jewish life. Their class consciousness and well-developed ethic of social justice, as well as the prophetic and traditional teachings within which they couched the labor and political conflict, were well understood in the Jewish community. Even Eastern European Jewish Orthodox leaders and newspapers who denounced the socialist leaders of the garment unions as demagogues gave their blessing to striking workers and affirmed the idea of unionization. This kind of support helped Jewish daughters stay in the movement. Although the daughters challenged some Jewish cultural norms – Newman, Schneiderman, Pesotta, and Cohn, for example, never married – the support legitimized their presence among the strikers and helped build a context of community and family sympathy for female activism.

The Hostility of Men

Despite the supportive environment and outstanding contribution of women to socialist union strength, many male union leaders regarded the women workers, and especially women organizers, with suspicion and hostility. Discrimination was rampant. Neither the ILGWU nor the ACWA stood strongly for the principle of equal pay for equal work, and women workers generally fared less well in contracts. Neither union was receptive to female leadership.

Executive positions at the local level continued to be monopolized by men. These conditions existed even where women outnumbered men as in White Goods Local 62 and Shirtwaistmakers Local 25, both of whose presidents were men. Furthermore, despite their majority in the ILGWU and their significant representation in the ACWA, only a small number of women rose to positions at the national level. Between 1916 and 1924, Fannia Cohn served as the only female voice on the ILGWU general executive board (GEB). Rose Pesotta was elected a vice-president in 1934, but as a solitary woman on the executive board, she thought her radical voice, though commanding, was a “voice in the wilderness” of petty-minded “male-cabals,” and she resigned in 1942. Bessie Abramowitz (Hillman) secured a seat on ACWA's GEB after serving as secretary-treasurer of District Council no. 6 in Chicago. And twenty-two-year-old Latvian-born Dorothy Jacobs (Bellanca), an organizer of the buttonhole makers' local in Baltimore, succeeded Abramowitz on the ACWA board.

Even those who achieved some distinction, however, revealed the difficulties involved in being the only women on the unions' boards. Fannia Cohn said that although she lived “a full, interesting, and satisfying life,” it was “not easy for a woman to be in a leading position, especially in the labor movement.” The prejudice and insensitivity of male leadership was not a monopoly of the socialist unions. The Socialist Party also took a long time to support women's unionism without reluctance.

The Socialist Party and the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL)

A disproportionate number of Jewish women were members and active recruiters for the party, and a small number were actually Socialist candidates, like Esther Friedman, who ran for the New York State Assembly several times. They were heavily involved despite the fact that the Socialist Party posture toward women was marked, for the most part, by disinterest and condescension. The party never wholeheartedly encouraged women to organize, and even when it officially recognized women in 1908 as a constituent element in the class struggle, it failed to understand the “Woman Question.” Socialists never fully faced the issues of women's low position in the labor market, the nature and significance of household labor for women, or the unique cultural baggage that women carried into the workplace. The “problems” of women were rooted, the party argued, in the system of private property – emancipation for everyone, including women, would arrive with the Cooperative Commonwealth. On tactical questions the Second Socialist International had already spoken the final word in the late nineteenth century: Socialist women were to remain loyal to the party and, unlike Newman and Schneiderman, resist the temptation to make cross-class alliances with other women. Class-consciousness was to be the ultimate loyalty, not gender.

While the recruitment of Jewish women into the Socialist Party outpaced recruitment in many other groups, the process was slow. A Jewish Woman's Progressive Society, a socialist group, emerged in New York and in Chicago in the 1890s and attracted an impressive roster of radical speakers before it disappeared during the depression of 1893. When the socialist Workmen's Circle (WC) was established in 1892, it formally endorsed participation of women but did little to encourage it. The WC reorganized in 1901, and separate ladies' branches were recognized for the first time. These branches attracted a sizable membership, but they were mostly extensions of the social networks among women married to Socialist Party men. The ladies' branches were not pathways for those ambitious to make significant contributions, and they failed to integrate women into the party's mainstream.

Only after 1909, when tens of thousands of Jewish women fought successfully for union recognition, did women leaders play an important part in the Socialist Party. The Women's National Committee (WNC), established in 1908, set out to recruit women directly into the party. But in order to maintain centralized party discipline, the WNC also sought to eradicate independent socialist women's organizations. They recruited successfully among the strike leaders and at the same time placed Socialist Party functionaries in important positions in the garment unions and in the Women's Trade Union League (WTUL), a reformist, middle-class organization that had proven a valuable ally in the women's labor movement.

Rose Schneiderman, who had achieved recognition during the 1909 strike, was one of several prominent recruits. And more long-standing socialists, including Pauline Newman and Clara Lemlich, also used their new, strike-gained visibility to the party's benefit. Newman became a paid organizer for the ILGWU and for several years preached the socialist message to union audiences. Lemlich joined the WTUL executive board and devoted herself to politics, especially the Socialist Party's woman suffrage campaign. There was, however, no increase in party membership. Instead, women trade unionists, including Jewish radicals, committed themselves even more deeply to their union duties.

Some Socialist Party stalwarts like Yiddish journalist Theresa Malkiel, who had been a member of the WTUL, turned on the middle-class women of that organization, blaming them for distracting women from socialism with the “false consciousness” of feminism. WTUL officials did acknowledge the Socialist Party's contributions to the labor movement in its internal reports, but they rarely praised socialists openly. And the WTUL, not the Socialist Party, emerged as the public champion of working women. Malkiel warned against continuing to cooperate with the “bourgeois” reformers, but of all the reform groups that rallied to the cause of labor, none was more effective in organizing women than the WTUL.

The WTUL, an organization that had provided funds, meeting space, and publicity, and whose middle-class women sometimes picketed, risking police arrest and assault, had helped secure important victories and roused many women to political activism. Socialists Pauline Newman and Rose Schneiderman, therefore, continued to work for the WTUL, even as they experienced some tension in the attempt to synthesize feminism and socialism. A male correspondent warned Schneiderman about her work in the feminist movement: “You either work for Socialism, and as a consequence for the equality of the sexes, or you work for women ... only and neglect Socialism. Then you act like a bad doctor who pretends to cure his patient by removing the symptoms instead of removing the disease itself.”

Class and Gender

Jewish socialist women, however, did not work for women only. They did not become full fledged feminists, at least not to the extent of putting the oppression of women above all else. The more radical and active women steered an uneasy course between their commitment to class solidarity and the promises of feminist reform. Jewish working women's politics grew out of their role as breadwinners, class-conscious Jews, and members of an ethnic community, and they appeared genuinely excited partners in a labor movement that included both sexes. Not only were the women demonstrating their ability to fight side by side with men; there was also the promise that the authentic comradeship and partnership of the day-to-day labor movement could be translated into romantic, respectable, companionate marriages. In the unions and in the party, women remained “junior” partners to be sure, but for most Jewish women this was preferable to a return to restrictive gender separation that had circumscribed their lives in the shtetls of Eastern Europe.

Yet, while they stressed the common ground they shared with men in the working-class community, the vast majority, possibly as high as 75 percent of Jewish women, favored female suffrage. The women of the Lower East Side of New York, between 1915 and 1917, produced more support for suffrage referenda than almost all other districts, including middle-class Protestant districts. And they did this in the face of the Socialist Party's lukewarm response to female suffrage, and despite the position of the Jewish Daily Forward, which carried columns by Jewish socialist luminaries warning women against placing too much emphasis on “political emancipation.”

These women stayed with socialism, even though the party continued in the main to treat women's issues as marginal “symptoms” of the class system. But in many places, and especially in Chicago and New York, Jewish women joined, and became prime leaders of, the many women's committees of the Socialist Party. They also stayed with socialist trade unionism even though, like Newman, Schneiderman, and Pesotta, their union brothers continued to be chauvinistic. But from 1913 on, a small group of Jewish women pressed for a greater measure of equality in the ILGWU and the ACWA, and semiautonomous women's institutions within the garment unions. Pauline Newman and Dorothy Jacobs Bellanca, among other Jewish leaders, argued persuasively that the mixed-gender branches were losing participation of female members who felt intimidated. In the ACWA, women activists eventually withdrew from the established locals and founded separate women's branches that cut across ethnic and occupational lines, bringing together all female workers in the men's clothing industry in a particular city.

Gender segregation had been advocated not as an ideological expression of “female difference,” but as a “tactical expedient” toward integration. By 1920, however, left-wing Jewish women in the ILGWU recognized that gender segregation not only had little attraction to the rank and file, Jewish or otherwise, but could actually lead to further exclusion of women, and so they promoted abolition of sex divisions. Even long-term advocates of women's rights, like Fannia Cohn and others, insisted on the primacy of the class struggle and promoted the idea that women and men had “much in common” and ought not to be segregated.

The decision by Jewish women to stay with the Socialist Party and garment unions, despite their second-class status in those institutions, meant that socialist women had the opportunity to prove what so many male comrades previously doubted – the ability of a militant minority to organize working women, and to mobilize these women for battle. Socialist Jewish women made strikes even over the objections of male leadership. And in the unions, they initiated important and enduring education, health, and recreation programs despite the doubts of male colleagues.

Feminism and Socialism

Between feminism and socialism, between the desire for civic participation and the equally compelling desire for domestic respectability, most Jewish immigrant daughters had found a middle way. Even when they married, as most did, Jewish women did not leave their politics behind. Among the leadership Cohn, Schneiderman, and Newman never married, but Abramowitz, Jacobs, Lemlich, and Malkiel did. In 1900, Malkiel organized married housekeepers into the Woman's Progressive Society of Yonkers, which later became Branch One of the Socialist Women's Society of Greater New York. Although for most radical Jewish women, home and family pushed sustained activism to the background, many nonetheless retained their union membership and participated as organizers, fund-raisers, and campaigners. And in the Great Depression of the 1930s, when political hopes for the Left flared again, many of the married women valiantly fought against evictions of the down and out, and struggled for the rights of the unemployed.

Women also participated in the extensive Jewish organizational network that was spawned by socialism and communism as these movements grew. Here they managed to combine family and community obligations with a dimension of personal independence. Some like Clara Lemlich Shavelson, who joined the Communist Party in 1936, managed to stay politically active despite the pull of home and family, and brought an early feminism into her household. Former working women (and future working women too) found jobs as teachers and administrators in Socialist Sunday schools and Yiddish-language shuln, and special places in children's camps, consumer and tenant committees, and labor defense and foreign relief societies. These activities were not direct political participation, but they represented an extraordinary contribution to the socialist labor movement and to social welfare in general. And they offered the Jewish woman a temporarily viable synthesis of her desire for self-sufficiency and fulfillment, her energy, her idealism, her class-consciousness, and the traditional culture out of which some of these aspirations and attitudes emerged.

Baum, Charlotte. "What Made Yetta Work? The Economic Role of Eastern European Jewish Women in the Family." Response 18 (Summer 1973): 32-38.

Buhle, Mary Jo. Women and American Socialism, 1870-1920. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1981.

Cohen, Rose. Out of the Shadow: A Russian Jewish Girlhood on the Lower East Side. Intro. By Thomas Dublin. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995. (First published 1918).

Davis-Kram, Harriet. "Jewish Women in Russian Revolutionary Movements." M.A. thesis, Hunter College, City University of New York (1974).

Dye, Nancy. "Creating a Feminist Alliance: Sisterhood and Class Conflict in the New York WTUL." Feminist Studies 2, no. 2 (1975): 361-375.

Endelman, Gary E. "Solidarity Forever: Rose Schneiderman and the Women's Trade Union League." Diss., University of Delaware (1978).

Glenn, Susan A. Daughters of the Shtetl: Life and Labor in the Immigrant Generation. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1990.

Kennedy, Susan Estabrook. If All We Did Was to Weep at Home. Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Press, 1979.

Kessler-Harris, Alice. "Organizing the Unorganizable: Three Jewish Women and Their Union."

Labor History 17, no. 1 (Winter 1976): 5-23.

Kramer, Sydelle, and Jenny Masur, eds. Jewish Grandmothers. Boston: Beacon Press, 1976.

Levine, Louis. The Women Garment Workers. New York: B.W. Huebsch, Inc., 1924.

Malkiel, Theresa. Diary of a Shirtwaist Striker. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1990. First published 1910.

Michels, Tony. A Fire in Their Hearts. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003.

Miller, Sally M. "From Sweatshop Worker to Labor Leader: Theresa Malkiel, a Case Study."

American Jewish History 68, no. 2 (December 1978): 189-205.

Miller, Sally M. "Other Socialists: Native Born and Immigrant Women in the Socialist Party of America, 1901-1917." Labor History 24, no. 1 (Winter 1983): 84-102.

Orleck, Annelise. Common Sense and a Little Fire. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Pesotta, Rose. Bread upon the Waters. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, Inc., 1944.

Pesotta, Rose. Days of Our Lives. Boston: Excelsior Publishers, 1958.

Quint, Howard. The Forging of American Socialism. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1953.

Scheier, Paula. "Clara Lemlich Shavelson: Fifty Years in Labor's Front Line." In The American Jewish Woman: A Documentary History. Edited by Jacob R. Marcus. Brooklyn, NY: Ktav Publishing, 1981.

Schneiderman, Rose. All for One. P.S. Eriksson, 1967.

Shannon, David. The Socialist Party of America. London: MacMillan, 1955.

Shavelson, Clara Lemlich. "Remembering the Waistmakers' General Strike, 1909." Jewish Currents 36, no. 10 (November 1982): 9-15.

Sorin, Gerald. The Prophetic Minority: American Jewish Immigrant Radicals, 1880-1920. Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Press, 1985.

Wolfson, Theresa. The Woman Worker and the Trade Unions. New York: International Publishers, 1926.

Manuscript and Oral History Collections

Amerikaner-Yiddishe Geshichte Be'al Pe [American Jewish Oral History]. YIVO, NYC. Cohn, Fannia. Papers. New York Public Library.

Pesotta, Rose. Papers. New York Public Library.

Schneiderman, Rose. Papers. Tamiment Institute.

Other Sources

Oral History of the American Left. Tamiment Institute, NYC.

Socialist Party. New York Papers and Minute Books. Taminent Institute.