International Ladies Garment Workers Union

The International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) was founded in 1900 by eleven Jewish men who represented seven local East Coast unions with heavy Jewish immigrant populations. Initially excluded from the union, women began to organize after the introduction of the shirtwaist, the surrounding working conditions of which gave women the grounds to join Local 25 of the ILGWU. The Uprising of the 20,000 in 1909, led by Clara Lemlich and directed against employer tyranny in the sweatshop, gave these women bargaining power and bolstered their numbers. Women garment workers went on to shape the ILGWU’s labor philosophy, advocating strongly for education as a means through which to reshape society to better support the working class.

The International Ladies Garment Workers Union was founded in 1900. The eleven Jewish men who founded the union represented seven local unions from East Coast cities with heavy Jewish immigrant populations. This all-male convention was made up exclusively of cloak makers and one skirt maker, highly skilled Old World tailors who had been trying to organize in a well-established industry for a couple of decades. White goods workers, including skilled corset makers, were not invited to the first meeting. Nor were they or the largely young immigrant Jewish workers in the newly developing shirtwaist industry recruited for the union in the early years of its existence. But these women workers still tried to organize.

Introduction of the Shirtwaist

The shirtwaist was a woman’s garment with a mannish touch: a buttoned front. Charles Dana Gibson, an illustrious illustrator of the time, popularized this daring design by featuring his handsome Gibson girl wearing a shirtwaist.

The introduction of the shirtwaist lent itself to a system of inside contracting where the work done by women was moved into factories and workshops, still under the control of a contractor but not within the household. As a result, women workers faced different kinds of control, regulation, and, ultimately, sexual harassment. However, the new system also provided larger work sites where numbers of women could gather together to talk about their grievances, among other things. Thus the possibility for unionizing increased. A handful of these women workers, goaded on by the intolerable sweatshop conditions in which they toiled, joined the shirtwaist makers’ Local 25 of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union.

The struggling local had few members, fewer finances, and virtually no bargaining power until the historic Uprising of the 20,000 in 1909. This was partly due to the men’s insistence that only “skilled” workers could effectively organize, partly to the sex-segregated nature of the industry, which kept women in relatively less skilled jobs, and partly to the rapid turnover of women garment workers who moved from job to job in search of better wages. Nonetheless, small strikes and work protests by women pockmarked the first decade of the century. Most of them were quickly lost. Then came the 1909 uprising, itself preceded by a two-month strike at the soon-to-be-infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Company.

The Uprising of 20,000

The uprising was more than a “strike.” It was the revolt of a community of “greenhorn” teenagers against a common oppression. The uprising set off shock waves in multiple directions: in the labor movement, which discovered women could be warriors; in American society, which found out that young “girls”—immigrants, no less—out of the disputatious Jewish community could organize; in the suffragist movement, which saw in the plight of these women a good reason why women should have the right to vote; and among feminists, who recognized this massive upheaval as a protest against sexual harassment. This strike and subsequent ones in the apparel industry stemmed from long days, low wages, manipulations of pay, and the denial of work in the absence of sexual favors, distinctive aspects of the garment trades.

The uprising had its Joan of Arc, a wisp of a “girl” arising out of nowhere, or so it seemed to the men who ran the union. Her name was Clara Lemlich [Shavelson]. She was not one of the scheduled speakers, although she had proved herself an outspoken activist and daring organizer in previous strikes. But she spoke the words that sparked the conflagration. The overflow meeting in the Great Hall at New York’s Cooper Union, the site of Abraham Lincoln’s historic speech on Union and Liberty, was to be addressed by Samuel Gompers, president of the American Federation of Labor; Benjamin Feigenbaum, later elected as a socialist to the New York State Assembly; Jacob Panken, later elected a judge; Bernard Weinstein, head of the United Hebrew Trades; Meyer London, a labor attorney and the first socialist to be elected to Congress from the Lower East Side; and Mary Dreier, a prominent progressive socialite who had been walking the picket line with the strikers and was head of the Women’s Trade Union League.

When Jacob Panken was introduced, he was interrupted by a high-pitched voice from the audience. “I want to say a few words,” she said. From the audience came a clamor of voices, “Get up on the platform.” Chairperson Feigenbaum sensed the mood of the moment. He ruled that since this girl was a striker and had been beaten up on the picket line, she should be heard. Panken acquiesced.

In what one press report called a “philippic in Yiddish,” Clara Lemlich concluded, “I offer that a general strike be declared now.” Although not everyone in the audience was conversant in Yiddish—there were many Italian immigrant workers in the garment industry—they all understood.

Feigenbaum reached into the Jewish past to endow the moment with a touch of tradition. He called upon all those present to raise their hand and to “take the old Jewish oath. If I turn traitor to the cause I now pledge, may this hand wither from the arm I now raise.”

The strike, directed against employer tyranny in the sweatshop, served many purposes, one of which was to draw the attention of suffragists to the plight of working women. Up to that time, those at the forefront of the fight for women’s right to vote came almost exclusively from the economic and educated elite in the United States. To these women, the conditions of the shirtwaist makers were evidence of what happens when women are denied a voice in the governance of their communities and country. The active resistance to economic exploitation of these young Jewish women indicated that they should, and could, add new legions to the ranks of the suffragists. Indeed, Jewish immigrants subsequently became outspoken supporters of suffrage, helping to pass the New York State law in 1917. As a consequence of the uprising, the crusades for the rights of working people as workers and of women as women and as citizens were coming together.

The lasting meaning of the uprising was summarized by Samuel Gompers at the American Federation of Labor convention after the shirtwaist strike. It “brought to the consciousness of the nation,” he declaimed, “a recognition of certain features looming up on its social development. These are the extent to which women are taking up with industrial life, their consequent tendency to stand together in the struggle to protect their common interests as wage-earners, the readiness of people in all classes to approve of trade-union methods on behalf of working women, and the capacity of women as strikers to suffer, to do, and to dare in support of their rights.”

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire

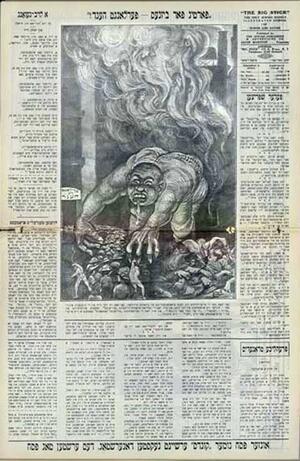

Inspiring as the uprising was, its immediate consequence in terms of working conditions was limited. This was especially true in the case of the Triangle Shirtwaist Company, whose brutal mistreatment of its employees was the original cause célèbre that set off the uprising and which remained unorganized. The Jewish employers of Triangle had been cited several times for violation of the city’s fire safety code; the company paid the fine and then went about doing its business as usual.

On March 25, 1911, a fire broke out in the Triangle factory. It claimed 146 lives, mainly Jewish women. These victims became the martyred dead in a cause that, in time, revolutionized labor conditions and labor relations in America. It led to more effective fire and safety regulations in New York State, and it inspired women like Rose Schneiderman of the Women’s Trade Union League to argue forcefully that legislation was less important than organization.

The ILGWU’s Mission: Education and Community Development

The large numbers of women garment workers in the ILGWU shaped its labor philosophy, despite the conspicuous absence of women among the union’s top leadership. The ILGWU looked upon the union not only as a means to protect and promote the immediate interests of garment workers but also as part of a greater international movement to convert a dog-eat-dog economic system into a global cooperative commonwealth. Its leaders viewed the class struggle as a classroom where working men and women would learn about the whys and hows of improving their personal lives and remolding the social order. For members to pay dues was vital, but it was equally important for them to pay attention to their own development and to their role in the reshaping of society. Through education, working people would become their own messiah.

Women, especially activists in Local 25, championed this mission. In 1916, spurred by Local 25, the union convention voted to establish an education department to be headed by Juliet S. Poyntz, a former history teacher at Barnard College. To supplement the teaching skills of this outsider, the union chose Fannia Cohn, for many years the only woman on the union’s general executive board, to apply her organizing skills as an insider to enroll members en masse in this novel grass-roots educational program. When Poyntz resigned in 1918 under pressure from the general executive board, Cohn, named as executive secretary of the education department, carried on under a male education director, and she generated one of the most remarkable worker education programs in America.

Under Cohn’s guidance, the ILGWU instituted a Workers University in New York City’s Washington Irving High School where union members attended lectures by such distinguished college professors as Charles Beard, Harry Carmen, and Paul Brissenden. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics noted in a 1920 report that “the first systematic scheme of education undertaken by organized [labor] in the United States was put in practice by the ILGWU.” It further reported that “up to the spring of 1919 eight hundred [members] had either completed one or more courses or were engaged in the study of various subjects.” Cohn greatly expanded the union’s educational offerings, setting up programs in Cleveland, Boston, and Philadelphia.

While the university was the jewel in the diadem of the union’s educational work, there were, in addition, eight Unity Centers that offered basic courses in literacy. Union leaders were trained in public speaking and parliamentary procedure. There were also classes in health—how to stay well. As the union grew, many of these activities proliferated. Members took classes on college campuses during the summer, and there was a formal Officers Training Institute, as well as intensive pretraining for citizenship and extensive education in health care.

Many of these, which became models for the entire American labor movement, derived from the early initiatives of Fannia Cohn. Women in Local 25, where the membership was more than 75 percent female in 1919, wanted the union to perform a social role that would create community and comradeship as well as loyalty to the union. So, for example, the ILGWU created vacation houses and developed a pioneer medical institution—the ILGWU Health Center. It was a unique and influential conception of unionization.

Decline and Resurgence of the Union

By 1919, drawing on their confidence gained from classes and discussion groups, women in Local 25 began to question why they had not a single woman officer. The demand for union democracy took hold. But soon women’s issues were taken over by male insurgents, many of them Communist Party organizers. Trusted women leaders like Fannia Cohn and Pauline Newman were caught in the middle between a battle of the “lefts and rights.” The political infighting seriously weakened the union; women declined as members from 75 percent to a mere 39 percent by 1924, and male union leaders were reluctant to start new organizing drives to unionize women.

In the 1930s, rejuvenated by the New Deal’s support of labor organizing, women once again came to dominate the membership of the ILGWU. And once again the issue of women’s leadership arose. Rose Pesotta was the only woman on the union’s executive board. When Miriam Speishandler of Local 22 was nominated as a delegate to the national convention, she took the opportunity to ask ILGWU president David Dubinsky why there were not more women on the executive board of a union that was 85 percent female. Pesotta’s visibility in California led to her election in 1934 as a vice president of the ILGWU, serving on the general executive board. Pesotta was conflicted about her ten years of service in that position. Sexism and a loss of personal independence continually troubled her, until she finally resigned from the position in 1942.

The heady days of the 1930s also led to such unusual innovations as the musical revue Pins and Needles. Written by Harold Rome, the successful musical ran for an impressive 1,108 performances in 1937 to consistently enthusiastic audiences who appreciated its humor, its political message, and its sharp social commentary. The show’s cast were all union members who effectively propagandized the trade union movement through song and dance

The ILGWU’s Contemporary Legacy

More recently, as the ILGWU’s membership has shifted from Jewish and Italian women to Latino, African-American, and Asian women, one Jewish woman has served as the union’s legislative voice in the halls of Congress for almost half a century. Unlike the other Jewish women of prominence in the union, Evelyn Dubrow was not an immigrant. She grew up in New Jersey and was educated at the New York University School of Journalism. When American labor, through the Congress of Industrial Organizations, began to reach into mass manufacture in the 1930s, Dubrow served as education director for the New Jersey Textile Workers of America. As a writer, she worked as secretary of the New Jersey Newspaper Guild from 1943 to 1946.

Subsequently she became national director of organization of the Americans for Democratic Action and a founder of the Consumer Federation of America. By her performance on the Hill, Dubrow has won recognition and admiration from those who know how the wheels of government run. In 1982 the Washington Business Review named her as one of D.C.’s top ten lobbyists, and in 1994 Washingtonian Magazine listed her as one of America’s top 100 women.

Although Evelyn Dubrow is distinguished for her political work, she was exceptional among the Jewish women in the union only in her official assignment to that mission. All of the women leaders mentioned were intensely political, as were many of the rank and file. For them it was never enough to have a union to ease and enrich the lives of those in the apparel industry. They dreamed of and worked for a movement that would someday transform the world into a place where the ideals of equality and justice for all would be a reality.

Glenn, Susan A. Daughters of the Shtetl: Life and Labor in the Immigrant Generation. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991.

Howe, Irving. World of Our Fathers: The Journey of East European Jews to America and the Life They Found and Made. New York: NYU Press, 1976.

ILGWU. Pauline Newman. 1986.

Kessler-Harris, Alice. “Organizing the Unorganizable: Three Jewish Women and Their

Union.” Labor History 17 (Winter 1976): 5–23. In Labor Leaders in America, edited by Melvyn Dubofsky and Warren Van Tine. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1987.

Kessler-Harris, Alice. “Rose Schneiderman and the Limits of Women’s Trade Unionism.” In Labor Leaders in America, edited by Melvyn Dubofsky and Warren Van Tine. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1987.

Leeder, Elaine. The Gentle General: Rose Pesotta, Anarchist and Labor Organizer. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993.

Levine, Louis. The Women’s Garment Workers. New York: B.W. Huebsch, 1924.

Orleck, Annelise. Common Sense and a Little Fire: Women and Working-Class Politics in the Unites States, 1900–1965. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Pesotta, Rose. Bread upon the Waters. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1945.

Seidman, Joel. The Needle Trades. New York: Farrar & Rhinehart, 1942.

Stein, Leon. Out of the Sweat Shop. Chicago: Quadrangle-New York times Book Co., 1977.

Stein, Leon. The Triangle Fire. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1962.

Stolberg, Benjamin. Tailor’s Progress. New York: Doubleday, Doran & Co., 1944.

Tyler, Gus. Look for the Union Label. London: Routledge, 1995.