Triangle Shirtwaist Fire

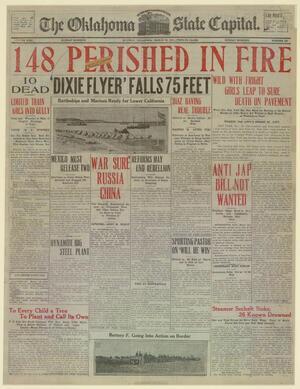

146 garment workers lost their lives in the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire in New York's Greenwich Village, which was one of New York's worst industrial accidents and covered by newspapers across the nation, including the Oklahoma State Capital, whose March 26, 1911 front page is displayed here.

Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress, Serial and Government Publications Division.

On March 25, 1911 a, fire erupted at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, resulting in 146 deaths and many injuries, most of them young, recently immigrated Jewish women. The trial of the proprietors resulted in acquittal. The owners, who collected their insurance and soon reopened their shop at a new address, offered to pay one week’s wages to the families of the victims. To the Jewish community, the unprecedented scope of the tragedy and its horrors were evocative of the pogroms that had been to date the greatest disaster to befall Jewry in modern times. In the wake of public protest and the wave of sympathy for working women, the New York State Committee on Safety was established and ever since then, the site of the fire has become the focus for labor activity.

The Fire and Trial

One of the worst industrial disasters in the history of New York City, causing 146 deaths and an unknown number of injuries, took place on Saturday, March 25, 1911, at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company. The workplace occupied the eighth, ninth, and tenth floors of the Asch Building located on the corner of Greene Street and Washington Place, off Washington Square. Isaac Harris and Max Blank, the Jewish owners of the factory, employed almost a thousand workers in busy seasons. On the day of the fire approximately five hundred workers were present. Victims of the fire were mostly recent immigrant Jewish women aged sixteen to twenty-three. The Triangle Shirtwaist Company was an anti-union shop and the site of the famous 1909 Uprising of the 20,000 for union recognition organized by the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) that swept the industry. Though some firms settled with the workers, the Triangle Shirtwaist Company refused to grant their demands, and most union members were discharged.

The fire probably started as a result of a lighted match dropped accidentally into a bin full of fabric scraps. It spread rapidly throughout the densely packed area of the shop. While many of the workers on the eighth floor escaped through the staircase, and those on the tenth floor escaped onto the roof, workers on the ninth floor were trapped by the fire. The employers had kept the escape exits locked to prevent theft and “stealing time,” and to keep out union organizers and prevent spontaneous walkouts. The sole existing fire escape bent in the heat and under the weight of those fleeing the fire, while the firefighters who arrived on the scene were not equipped with ladders of sufficient height. The desperate workers tried to escape by jumping onto nets, trampolines, and blankets extended below, which collapsed under the weight of many women jumping at once. Others leaped from windows, their clothes ablaze, and were killed on impact, while the rest were burned to death.

The trial of the proprietors resulted in acquittal. The owners, who collected their insurance and soon reopened their shop at a new address, offered to pay one week’s wages to the families of the victims. In 1914 they were ordered by a judge to pay damages of seventy-five dollars to each of the twenty-three families of victims who had sued.

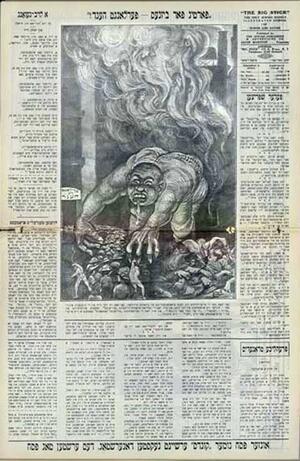

Effect on Jewish Community

To the Jewish community, the unprecedented scope of the tragedy and its horrors were evocative of the pogroms that had been the greatest disaster to befall Jewry in modern times. A special relief fund distributed money, collected within the Jewish community and by outside organizations, to dependents living in New York, Russia, Austria, and even Palestine. The outrage and the grief galvanized the Jewish community and the progressive public into action. The first protest meeting, organized by the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL)—a traditionally important ally of ILGWU since the days of the 1909 strike—was attended by leaders of civic and labor organizations who demanded that a committee be appointed to study the tragedy and draft proposals for health and safety legislation. At a meeting of the Local 25, ILGWU, with a number of survivors in attendance, there were calls for drastic measures against those guilty of imposing intolerable work conditions. The largest meeting, organized by Anne Morgan of the WTUL, took place at the Metropolitan Opera House on April 2, 1911, and was attended by civic leaders, representatives from an array of institutions and progressive organizations, and union representatives. The meeting called for public pressure for legislation to ensure safety in the workplace. In her impassioned speech, however, Rose Schneiderman, the leader of the strike in the Triangle factory, railed against the civic leadership and their neglect, and called on all working people to organize and take action. The culminating event took place on April 5, the day designated for the funeral of seven unidentified victims. A huge march sponsored by Local 25, ILGWU, was a silent but powerful demonstration that drew a crowd of 500,000 mourners.

Aftermath

In the wake of public protest and the wave of sympathy for working women, the New York State Committee on Safety was established. Among its participants were forerunners of the New Deal, including Frances Perkins, Henry L. Stimson, and Henry Morgenthau, Sr. Following the committee’s recommendations, the New York State Legislature set up a Factory Investigating Commission chaired by Robert F. Wagner, Sr., and Alfred E. Smith. In its four-year term, the commission investigated work conditions in shops, factories, and tenement houses, and was instrumental in drafting new factory legislation. These measures limited the number of occupants on each factory floor relative to the dimensions of staircases, prescribed automatic sprinkler systems, and drafted employment laws to protect women and children at work.

Ever since then, the site of the fire has become the focus for labor activity. The tragedy is still being commemorated by annual demonstrations, by gatherings of women workers, and by union events, emphasizing the importance of the Occupational Safety and Health Act. Considered the worst disaster in New York City until the destruction of the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire remains one of the most vivid symbols for the American labor movement of the essential need to ensure a safe workplace environment.

Berger, Joseph. “100 Years Later, the Roll of the Dead in a Factory Fire is Complete.” New York Times, February 20, 2011.

Cannon, Donald J. The Encyclopedia of New York City, s. v. “Triangle Shirtwaist Fire,” ed. by Kenneth T. Jackson. New Haven: 1996.

Drehle, David von. Triangle: The Fire That Changed America. New York: 2003.

Stein, Leon. The Triangle Fire. New York: 1962. Reprinted New York: 2001, introduction by William Greider.

Triangle Fire file. Wagner Labor Archives, Tamiment Institute Library, New York University, NYC.