Pauline Newman

Institution: The Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

Pauline Newman played an essential role in galvanizing the early twentieth-century tenant, labor, socialist, and working-class suffrage movements. Newman began working in a hairbrush factory at age nine and by eleven was laboring in the notorious Triangle Shirtwaist Factory. In 1909, she helped organize the Uprising of the 20,000, the largest strike of women workers to date, and was made the first woman general organizer of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. She was a regular contributor to a number of labor union periodicals on the subject of women workers. Newman continued to work for the ILGWU for more than seventy years—first as an organizer, then as a labor journalist, a health educator, and a liaison between the union and government officials.

Introduction

Pauline Newman was a labor pioneer and a die-hard union loyalist once described by a colleague as “capable of smoking a cigar with the best of them.” The first woman ever appointed general organizer by the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU), Newman continued to work for the ILGWU for more than seventy years—first as an organizer, then as a labor journalist, a health educator, and a liaison between the union and government officials. Newman played an essential role in galvanizing the early twentieth-century tenant, labor, socialist, and working-class suffrage movements. She also left an important legacy through her writings, as one of the few working-class women of her generation who chronicled the struggles of immigrant working women.

An acerbic woman whose unorthodox tastes ran to cropped hair and tailored tweed jackets, Newman loved the labor movement. She referred to the ILGWU as her “family” and believed that it was, for all its flaws, the best hope for women garment workers. Still, Newman was a pragmatic feminist who understood that most union leaders were only marginally interested in the concerns of working women. So, along with her union work, she campaigned throughout her life for labor legislation to protect women workers, and she forged alliances with progressives of all classes.

Vice president of the New York and National Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL) during the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, Newman was part of a cross-class circle of women reformers that included Eleanor Roosevelt, Rose Schneiderman, and Frieda Miller. Miller, who was Newman’s partner of fifty-six years, was New York State industrial commissioner and later U.S. Women’s Bureau chief. This circle of women shaped the body of laws and government protections that most workers now take for granted.

Newman’s career was a balancing act. Torn between the gruff, male-dominated Jewish socialist milieu of the ILGWU and the more nurturing “women-centered” Women’s Trade Union League, Newman chose, for personal as well as political reasons, to divide her energies between the two. Through the WTUL, she found an alternative family of women who provided the emotional and political support so essential for a woman who eschewed the traditional protections of marriage and family. Through the union, she maintained a connection to the world of Jewish socialism in which she was raised and which was central to her identity.

Family and upbringing

Pauline Newman was born to deeply religious parents in Kovno, Lithuania, sometime around 1890. (The exact date of her birth was lost when her family emigrated.) She was the youngest of four children, three girls and a boy. Her father taught Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmud to the sons of wealthy men. Her mother supported the family by buying fruit from peasants in the countryside and selling it at the Kovno marketplace.

Her activist career began when, as a child, she had to fight for the right to an education. First the Kovno public school excluded her because her family was Jewish and poor. Newman was rebuffed again by the local rabbi when she requested permission to attend the all-boy heder [religious school]. After further lobbying, Newman won the rabbi’s permission to attend Sunday school classes, where she learned to read and write Yiddish and Hebrew, but he would not allow her to study religious texts. Undaunted, she begged her father to let her sit in on the Talmud classes that he taught. He relented, but was unable to explain to his daughter’s satisfaction why she and other girls and women had to be restricted to a curtained-off balcony in the synagogue. Newman would later recall her resentment at the privileges accorded to males in Jewish education and worship as the spark for her lifelong fight against sex discrimination.

When Newman’s father died suddenly in 1901, her mother decided to take her three daughters to New York City, where her son had already settled. At age nine, Newman went to work in a hairbrush factory. Two years later, she began working among other children in the “kindergarten” at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, the most infamous of early twentieth-century garment shops.

Political Education and Early Activism

Depressed by the grim working and living conditions on the Lower East Side, Newman took solace in the worker-poetry she read in the socialist Yiddish press. Like many Jewish immigrants, Newman got her first education in socialism and trade unionism through the popular newspaper the Jewish Daily Forward. She joined the Socialist Literary Society at age fifteen and began to school herself in the social realist literature that she hoped to emulate. Charles Dickens was a particular favorite. Through her reading, she perfected her English-language reading and writing skills. Believing that literature would both comfort and radicalize her fellow workers as it did her, Newman organized after-work study groups at Triangle. These became the basis for the women’s unions she would soon organize.

In 1907, with New York City in the grip of a depression and thousands facing eviction, the sixteen-year-old Newman took a group of “self-supporting women” to camp for the summer on the Palisades above the Hudson River. There they planned an assault on the high cost of living. That winter, Newman and her band led a rent strike involving ten thousand families in lower Manhattan. It was the largest rent strike New York City had ever seen, and it catalyzed decades of tenant activism, which eventually led to the establishment of rent control. As the leader of the strike, Newman came to the attention of the Socialist Party, which ran her for secretary of state of New York the following year. Women did not yet have the vote in New York, but Newman used the campaign as an opportunity to stump for woman suffrage.

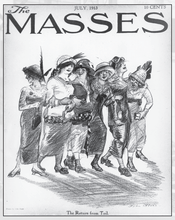

At this time, she began organizing women garment workers in shops throughout lower Manhattan, paving the way for the Uprising of the 20,000 of 1909—the largest strike by American women workers to that time. During the long, cold months of the strike, Newman met with wealthy women, explaining the horrific conditions under which shirtwaist dresses were manufactured. Drawing on her readings of English literature to come up with images that native-born affluent women could relate to, she won the sympathy of many of New York’s wealthiest. Some of them even decided to join the garment workers’ picket lines to stop police brutality against the strikers.

International Ladies Garment Workers Union

In recognition of her key role in organizing and sustaining the strike, Newman was appointed the first woman general organizer for the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. From 1909 to 1913, she toured the United States, organizing garment strikes in Philadelphia, Cleveland, Boston, and Kalamazoo, Michigan. She also stumped for the Socialist Party in the freezing, bleak coal-mining camps of southern Illinois and campaigned for woman suffrage for the Women’s Trade Union League. It was a lonely and frustrating few years for Newman, because she felt that the union leadership had little interest in organizing women and that her work was undervalued and undermined at every turn.

Newman was devastated by the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire of March 25, 1911—in which 146 young workers lost their lives, most of them immigrant Jews and Italians. Newman, who had worked at the factory for seven years, knew many of the victims. Her grief made her anxious to accept a post, in 1913, with the Joint Board of Sanitary Control, established by New York State to improve factory safety standards. Newman inspected industrial shops and lobbied state legislatures for wage, hour, and safety legislation for women workers. Through this job, she met Frances Perkins, then an activist for the Consumers League, later to become Franklin Roosevelt’s secretary of labor. Perkins and Newman took state legislators on tours of the worst factories in the state. Newman gained the respect of these political figures, who would call on her for advice or consultation many times over the next half century.

In 1917, the Women’s Trade Union League dispatched Newman to Philadelphia, to build a new branch of the league. There she met a young Bryn Mawr economics instructor named Frieda Miller. Miller, who was chafing at the constraints of academic life, gladly left academia to help Newman with her organizing. Within the year, the two were living together. It was the beginning of a turbulent but mutually satisfying relationship that would last until Miller’s death in 1974. In 1923, the two women moved to New York’s Greenwich Village, where they raised a daughter together. Though lesbian families were not openly discussed in the 1920s, their family seems to have been accepted by government and union colleagues.

In 1923, Newman became educational director for the ILGWU Union Health Center, the first comprehensive medical program created by a union for its members. Newman would retain that position for sixty years, using it to promote worker health care, adult education, and greater visibility for women in the union. She became a beloved and highly respected mentor to young women in the union. She also promoted the cause of women in trade unions through her positions as vice president of the New York and National Women’s Trade Union Leagues.

Later life

From the late 1920s on, Newman worked for and helped to shape new government agencies charged with the task of improving labor conditions for women workers. She consulted frequently for New York State on minimum wage and safety codes for women workers. She also served on the U.S. Women’s Bureau Labor Advisor Board, the United Nations Subcommittee on the Status of Women, and the International Labor Organization Subcommittee on the Status of Domestic Laborers.

Socially, Newman and Miller—who began a successful career in government in the 1920s—were part of the circle of women who surrounded Eleanor Roosevelt in the 1920s and 1930s. They were both regular guests at Val-Kill, the home that Franklin built for Eleanor Roosevelt near the family mansion at Hyde Park. And, during the mid-1930s, Newman visited the White House with some regularity. In 1936, she received national news coverage when Eleanor Roosevelt asked her to bring a group of young women garment and textile workers to stay as guests of the first lady for a week at the White House.

After World War II, Newman and Miller were commissioned by the U.S. Departments of State and Labor to investigate postwar factory conditions in Germany. During the Truman years, Newman addressed the White House Conference on the Child and served as a regular consultant to the U.S. Public Health Service on matters of child labor and industrial hygiene.

Newman continued to work for the ILGWU until 1983, writing, lecturing, and advising younger women organizers. During her seventy-plus years with the union, she waged a constant struggle to convince male leaders to acknowledge the needs and talents of women workers.

Legacy

With the revival of the feminist movement in the 1970s, the elderly Newman came to be seen as a feminist hero. In 1974, the Coalition of Labor Union Women honored her as a foremother of the women’s liberation movement. During the 1970s and 1980s, Newman became a living witness to the sweatshop conditions that prevailed during the early part of the twentieth century. She spoke regularly to historians and reporters and to groups of young women workers, her heavily wrinkled face and timeworn voice telling as much as her words about her decades of struggle on behalf of the labor movement. Newman’s dedication to writing also made her a valuable resource for scholars of women and trade unionism.

From 1909 to 1913, Newman was a regular contributor to the New York Daily Call, Progressive Woman, and the WTUL publication Life and Labor. From 1913 to 1918, she had a regular column in the Ladies Garment Worker entitled “Our Women Workers.” She continued to write for WTUL publications until 1950 and for the ILGWU newspaper Justice through the 1960s. The stories, columns, and reportage that she left behind form an important part of her historical legacy.

Pauline Newman died in 1986 at the home of her adopted daughter, Elizabeth Burger. She was approximately ninety-six years old. Newman’s death evoked a deep sense of loss in the ILGWU and among women trade unionists more generally. She had made her balancing act work and carved out a niche for herself as a liaison. Standing with one foot in the male-dominated labor movement and one foot in the cross-class world of women reformers, she touched a great many people. It is not easy to sum up Newman’s career. Her contributions as an organizer, a legislative expert, a writer, and a mentor to younger women activists were profound and wide-ranging. Her historical significance far exceeds any official title that she held.

Buhle, Mari Jo. Women and American Socialism, 1870–1920 (1981).

Fink 269–270.

Kessler-Harris, Alice. “Organizing the Unorganizable: Three Jewish Women and Their Union.” Labor History (Winter 1976).

Neidle, Cecyle. America’s Immigrant Women (1975).

Newman, Pauline M. Oral history interview by Barbara Wertheimer, and Papers. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe College, Cambridge, Mass..

Orleck, Annelise. Common Sense and a Little Fire: Women and Working-Class Politics, 1900–1965 (1995).