Bessie Abramowitz Hillman

Bessie Abramowitz devoted her life to unions, organizing her first strike at fifteen, announcing her engagement on a picket line, and continuing her efforts for workers’ rights until her death. Abramowitz immigrated to America at fifteen and found work in a garment factory while attending night school at the famous Hull House, run by suffragist Jane Addams. She spearheaded walkouts over pay cuts and poor conditions, inspiring her future husband, Sidney Hillman, to join and lead strikes himself. Abramowitz organized workers for the Women’s Trade Union League along the East Coast before becoming education director of the Laundry Workers Joint Board in 1937. Abramowitz Hillman remained active in union activities until her death in New York City, on December 23, 1970, at age eighty-one.

Family and Immigration to the United State

“I was Bessie Abramowitz before he was Sidney Hillman.” Bessie Abramowitz Hillman, wife of famed labor leader Sidney Hillman (1887–1946), was a militant labor movement leader before her husband became involved and remained a union stalwart her entire life.

Bas Sheva Abramowitz (“Bessie” was created by an Ellis Island immigration officer) was born on May 15, 1889, in Linoveh, a village near Grodno in Russia. She was one of ten children born to Emanuel Abramowitz, a commission agent, and Sarah Rabinowitz. In 1905, Bessie, who spoke only Yiddish and some Russian, joined an older cousin in immigrating to America. Most 1905 immigrants fled czarist oppression and anti-Jewish violence, but Bessie reported that her aim in leaving home was to escape the services of the local marriage broker.

Becoming a Labor Activist

Arriving in Chicago, where she had some distant relatives, the fifteen-year-old found a job as a button sewer in a garment factory and enrolled in night school at Hull House. When she organized a shop committee to protest working conditions and pay of three dollars for a sixty-hour week, she was fired. Looking for other work, she found herself on an employers’ blacklist and finally took a job, under an assumed name, at the Hart, Shaffner, and Marx clothing firm.

In September 1910, the twenty-year-old rebel again fought back, now against a cut of a quarter of a cent in the four-cent piece rate for sewing buttons on pants. She led a walkout of sixteen young women, an outburst at first viewed with amusement by most other workers in the plant, including Sidney Hillman, a twenty-four-year-old Lithuanian-born cutter. As the young women persisted, however, they gained adherents, and by mid-October most of the eight thousand workers at Hart, Shaffner, and Marx were out, soon joined by thousands in other plants. Sidney Hillman, too, followed the lead of the young women, joining the strike three weeks after its initiation and soon emerging as a strike leader. The strike won the support of Jane Addams of Hull House and its Women’s Trade Union League, which hired Bessie Abramowitz as an organizer.

On the union barricades, Bessie and Sidney’s friendship blossomed into a romance, and they were secretly engaged in 1914. Since both were sending money back to their families, an immediate marriage seemed impossible in that time of nonworking wives. In late 1914, garment workers in Chicago, New York, and other clothing centers split from the conservative United Garment Workers to form the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, and Bessie Abramowitz, then a business agent for a vestmakers’ local, was elected to its general executive board. She became a leader in the campaign to draft Sidney Hillman, who, a few months earlier, had taken a job in New York City with the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, to be president of the new union. He accepted and, during 1915, the young couple again fought together in an industrywide strike for the union shop.

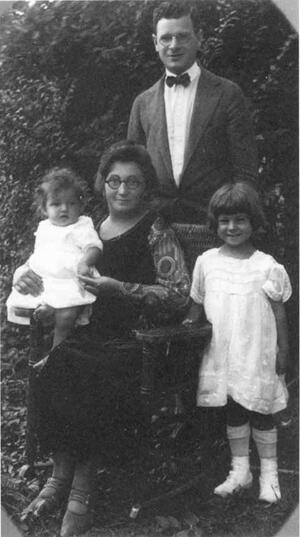

The two lovers announced their engagement publicly by heading, arm-in-arm, the clothing workers’ contingent in the Chicago May Day parade of 1916. They were married on May 3, 1916. They moved to New York City, headquarters of the new union, and from then until 1946, when Sidney Hillman died, all of Bessie Hillman’s considerable union work was performed as an unpaid volunteer.

A daughter, Philoine, was born in 1917 and another, Selma, in 1921. Hillman continued to do Women’s Trade Union League volunteer work at home, and in 1924 she returned to active union work. She organized workers in Pennsylvania, Ohio, upstate New York, Connecticut, and elsewhere. Her Yiddish accent presented no real barrier in organizing nonimmigrant workers, who saw her devotion to the cause and her signal role in creating the union.

In 1937, Bessie Hillman became education director of the Laundry Workers Joint Board, an affiliate of the Amalgamated. She emphasized cultural programs, as well as union leadership education, and gave early performing opportunities to, among others, Zero Mostel, Judy Holliday, and Sam Jaffe, continuing to back these artists when some of them were blacklisted for political reasons. In the Laundry Workers, a union with many nonwhite workers, Bessie Hillman became strongly involved in civil rights work, a dominant concern for the rest of her life.

During World War II, while her husband forged strong political bonds between labor and the Roosevelt administration, Bessie Hillman helped lead the union’s war efforts. She was named by Governor Herbert H. Lehman to the advisory board of the New York Office of Price Administration.

Jewish Identity

The Hillmans’ home life was determinedly secular. While Sidney Hillman became a close friend of Rabbi Stephen Wise, the noted Zionist and leader of Reform Judaism, the rabbi’s influence was limited to moral and political issues. Yet the Hillmans were firm in identifying as Jews. They spoke Yiddish at home and, while their daughters received no religious training, Jewish holidays were observed as family celebrations. When Jews, including some of Bessie Hillman’s brothers and sisters, fell victim to the Holocaust, the Hillmans protested vigorously. Their strong support of the war effort in the 1940s was, in large measure, part of their fight against the Nazi campaign to wipe out Jews. In 1947, Bessie Hillman traveled to Europe on a union-sponsored mission to examine the problems of displaced persons.

When Sidney Hillman, who insisted on a standard of living no better than that of a cutter in his union, died in 1946, he left virtually no estate. The Amalgamated hired Bessie Hillman as a paid vice president in charge of the union’s education programs. She spoke at union conferences, helped organize summer schools for rank-and-file leaders, and played a significant role at the union’s conventions, both as an inspirational link with the past and as a gadfly urging the union to greater efforts for civil rights, peace, and economic justice.

Over the years, Bessie Hillman served with the CIO and AFL-CIO Civil Rights Committees, the CIO Community Services Committee, the National Consumers League, the American Labor Education Service, Inc., the Committee on Protective Labor Legislation, the American Association for the United Nations, the Child Welfare Committee of New York, and the Defense Advisory Commission on Women in the Services, and she was appointed by President John F. Kennedy to the President’s Commission on the Status of Women.

Bessie Abramowitz Hillman remained active in union activities until her death in New York City, on December 23, 1970, at age eighty-one.

Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America. Archives. Cornell University School of Industrial and Labor Relations, Ithaca, N.Y.

Fraser, Steven. Labor Will Rule: Sidney Hillman and the Rise of American Labor (1991).

Josephson, Matthew. Sidney Hillman: Statesman of American Labor (1952).

Pastorello, Karen. A Power Among Them: Bessie Abramowitz Hillman and the Making of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (2008).