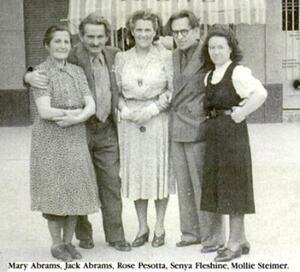

Rose Pesotta

Creative Commons License. Photo from the Triangle Fire Open Archive. Contributed by David Bellel

Rose Pesotta (Rakhel Peisoty until Ellis Island changed her name) was born in 1896, the second of eight children, into a middle-class family in the Ukraine. Pesotta attended Rosalia Davidovna’s school for girls, with its Russian curriculum and its clandestine classes in Jewish history and Hebrew. After two years at the school, she was needed at home to help care for her siblings, and home tutoring replaced formal schooling. Her formal education was complemented by political training in the local anarchist underground, which she joined with her older sister.

Pesotta immigrated to America with her sister in 1913 to escape an arranged marriage. Once in New York, Pesotta began working in various shirtwaist factories, and struggled to learn English. Soon, she joined Local 25 of the ILGWU. The local became a base for her union career. In 1915, she helped the local form the first education department in the ILGWU, and in 1920 she was elected to Local 25’s executive board. Rose also continued her studies at the Bryn Mawr Summer School for Workers, and between 1924 and 1926, she was a student at Brookwood Labor College. During the 1920s, she played a key role in the union’s chronic struggles with communists. Grateful union officials recognized Pesotta’s contributions by appointing her as an organizer in the late 1920s.

Pesotta brought a charismatic personality, boundless energy, and a unique ability to empathize with the downtrodden to the organizing field. In 1933, she spearheaded the Dressmakers General Strike in Los Angeles in the face of anti-picketing injunctions, hired thugs, and communist dual unions. She mobilized the largely Mexican labor force through Spanish-language radio broadcasts and ads in ethnic newspapers. Although the strike was not successful, Pesotta’s leadership established her as one of the most gifted organizers of the union.

Pesotta’s visibility in California led to her election in 1934 as a vice president of the ILGWU, serving on the general executive board – the first woman to hold this high post.

Between 1934 and 1944, though, Pesotta was one of the most successful organizers in the United States. She carried the union message to workers in Puerto Rico, Detroit, Montreal, Cleveland, Buffalo, Boston, Salt Lake City, and Los Angeles. On loan from the ILGWU to the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), she joined the great labor upheavals of the 1930s in Akron, Ohio, and Flint, Michigan. In 1944, Pesotta refused a fourth term on the CIO General Executive Board, with a brief critical statement that “one woman vice president could not adequately represent the women who now make up 85 percent of the International’s membership of 305,000.”

Following her resignation from union office, Pesotta published two memoirs: Bread upon the Waters (1945) and Days of Our Lives (1958). She worked briefly for the B’nai B’rith Anti-Defamation League, giving lectures about anti-semitism and racism, and for the American Trade Union Council for the Histadrut, Israel’s labor organization. But she supported herself during those years largely with factory work.

Anarchism and Judaism are key to understanding Pesotta’s identity and sense of self. Although first introduced to anarchist philosophy in Europe, Pesotta found community and support for her libertarian beliefs in the alternative culture of American anarchism. Anarchism was her ethical center. It celebrated the inherent goodness of the individual and rejected private property, the state, and authority. Pesotta served as secretary of the anarchist paper The Road to Freedom and was a key member of the Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee. Like her friend Emma Goldman, Pesotta was persecuted for her political beliefs and was arrested during the Red Scare of 1919 as an “alien subversive.” Unlike Goldman, she avoided deportation and became an American citizen.

For Pesotta, anarchism was inextricably enmeshed with Jewish culture and communities. Although not religiously observant, Pesotta always identified herself as Jewish. The Holocaust and the foundation of Israel deepened her sense of herself as a Jew and toward the end of her life she became a committed Zionist, involved with the Labor Zionist movement. She dedicated her second book to the memory of the Jewish civilization destroyed by the Nazis.

Pesotta died in December 1965 after a brief illness.

This biography is adapted from Ann Schofield’s article on Rose Pesotta in Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia.