Sionah Tagger

Sionah Tagger was one of the earliest modern Israeli women artists to have been born in Erez Israel; her parents, whose origins go back to Spain, were among the founders of Tel Aviv. Tagger played an important part in the development of modern painting in Palestine in the 1920s and 1930s. In the 1920s, in contrast to the Romantic Orientalist tradition that prevailed, Tagger became interested in the contemporary scene around her. As a native-born artist, she was unencumbered by a history of “diasporic,” foreign artistic styles and was interested first and foremost in the local and the contemporary. Her work shows the influence of Expressionism, Cubism, and Futurism. She was among the first members of Israel’s Association of Painters and Sculptors and a regular participant in its exhibitions.

Sionah Tagger was one of the earliest modern Israeli women artists to have been born in The Land of IsraelErez Israel. She played an important part in the development of modern painting in Erez Israel in the 1920s and 1930s, when the country’s artistic center moved from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv. Tagger was among the first members of Israel’s Association of Painters and Sculptors and a regular participant in its exhibitions, and she was among the founders of the Artists’ Colony in Safed.

Early Life and Family

Tagger’s parents, Shmuel and Sultana Tagger, were among the founders of Tel Aviv. The Tagger family’s origins go back to Spain. Following the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in the late fifteenth century, the family moved to Holland, and later to Germany and to Bulgaria. Shmuel Tagger immigrated to Palestine in 1868 from Bulgaria, while he was still a child. In 1890, the 22-year-old Shmuel married Sultana, daughter of Yeshiah Becher-Yeshiachi, a wealthy resident of the Old City in Jerusalem anda leading figure in Jerusalem’s veteran Jewish community who was later active in the Jewish community of Jaffa.

After their wedding, the young couple moved to Nahalat Shiva, a new neighborhood outside the walls of the Old City. They then moved to Jaffa, where Shmuel set up a business importing furniture and trading in leather. Shmuel and Sultana were among the first residents of Aḥuzat Bayit, the Jewish suburb of Jaffa founded in 1909 that would become Tel Aviv. The Tagger family had eight children: three daughters and five sons. Sionah, the oldest girl, was born in Jaffa on August 17, 1900. The family later moved to Rothschild Boulevard in Tel Aviv, where they lived in the city’s first multi-story apartment building.

Tagger attended the Yehieli school for girls, which was first located in Jaffa and later moved to the Neve Zedek neighborhood of Tel Aviv. She continued her studies at the Levinsky Seminary. As the daughter of a traditional Descendants of the Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal before the explusion of 1492; primarily Jews of N. Africa, Italy, the Middle East and the Balkans.Sephardi family, Tagger had to insist on taking her own path. She was an independent woman with a feminist mindset, without ever defining herself explicitly as such.

Artistic Education

When artist Joseph Constantinovsky (later known as Constant) and painter Yitzhak Frenkel opened a painting studio at the Hatomer artists’ cooperative in Tel Aviv, Tagger begged her parents to let her take evening courses there. Her mother did not understand why she wanted to study painting, since she was expected to marry, but her more liberal father agreed, partly because his daughter had excelled in painting at school and partly because he was well off and could afford to pay for her studies. Attending the studio in 1919–1920, she absorbed the influence of Russian Cubo-Futurism from her teachers, who had come from Odessa.

When the studio closed after a year, Tagger demanded to continue her art studies at the Bezalel Academy in Jerusalem, despite her parents’ opposition. They finally agreed to let her move to Jerusalem, on the condition that she would live in her grandfather’s home. She studied at Bezalel in 1921–1922 and upon finishing decided to go to Paris, though her parents again opposed the journey. Determined to do as she wished, Tagger worked for a year to save the money she needed to overcome her parents’ opposition. As she later observed, everything she did ran against what was accepted in a respectable Sephardi family.

Art was always Tagger’s first priority, even after her marriage in 1933 to Michel-Mordechai Katz, the birth in 1934 of her son Abraham (Katz-Oz, who would become a Knesset member), and later her divorce. She explained her separation from her husband on the grounds that he did not accept the long hours that she devoted to her art, to the point that she did not always get around to preparing meals. In fact, according to her son, she never cooked. She was entirely caught up in her painting and in Tel Aviv’s bohemian society. She and her husband parted in 1940; Michel remarried, while Sionah remained a single mother and had to cope with the economic difficulties that entailed. But even with her livelihood depending upon her art, she insisted on devoting herself wholly to painting. Her independence again came to the fore during World War II, when she volunteered, from 1940 to 1942, in the A.T.S. (Auxiliary Territorial Service), the women’s brigade of the British Army. She later joined the Haganah.

Developing a New Style

In the 1920s, in contrast to the Romantic Orientalist tradition that characterized the landscapes and figure paintings then being produced in Bezalel, Tagger, like other “modernist” artists working mainly in Tel Aviv, become more and more interested in the contemporary scene around her, as well as its cultural heroes. Rustic Arabs or Yemenites standing in for the land’s ancient Jewish inhabitants were replaced by pioneers, writers, poets, and public figures of the here and now, as exemplified by Tagger’s painting of poet Avraham Shlonsky (1900–1973).

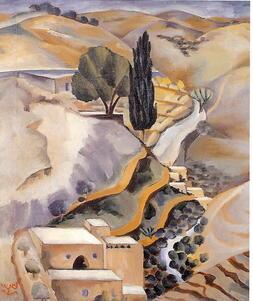

Similarly, old-time scenes of Jerusalem, with its holy places and olive trees, were replaced by scenes of the countryside, as in her landscape of Lifta, an Arab village near Jerusalem, and her paintings of Tel Aviv, Jaffa, and Safed.

Despite her recoiling from the orientalism of Bezalel, Tagger often painted portraits of Sephardi women. Rather than expressing a romantic or exotic sentimentality, Tagger painted the milieu and family in which she herself had grown up. The Sephardi women who appear in many of her paintings are members of her own family—her mother, sisters, and friends—as, for example, in her portrait of a girl in purple, her sister Shoshana.

Today, some see in these portraits a further expression of Tagger’s independence, as a woman and specifically a Lit. "Eastern." Jew from Arab or Muslim country.Mizrahi woman. However, to use the term “Mizrahi” in relation to Tagger is anachronistic; it was coined only after the establishment of the state, and attitudes toward Sephardim in the early decades of the twentieth century were not the same as those later directed toward Mizrahim. In old-time Tel Aviv and Neve Zedek, established Sephardi families lived side by side with Jews of European origin and their descendants, including most of North and South American Jewry.Ashkenazim.

As a native-born artist, Tagger was unencumbered by a history of “diasporic,” foreign artistic styles; she was interested first and foremost in the local, but also in the contemporary, including new international trends in art. Her work shows the influence of Expressionism, Cubism, and Futurism, which she had already encountered during her period of study in the Hatomer studio with Constantinovksy and Frenkel, and also through her acquaintance with the Peremen Collection.

Integrating European Modern Art Influences

Arriving in Erez Israel from Odessa in 1919 on the SS Ruslan (a kind of Israeli “Mayflower”), Yaakov Peremen, an intellectual and Zionist activist who was also an enthusiastic art collector, brought with him a collection of some 200 works of modern art by 25 prominent Russian Jewish artists, along with his large library of books on linguistics and Hebrew culture. Peremen’s ideas provided an alternative to those of Boris Schatz, the founder of Bezalel, and it was his intention to nurture modernist Israeli art in the spirit of the avant-garde modern art tradition from which he hailed. From the turn of the twentieth century through the 1920s, a major avant-garde movement in art had developed in Russia, influenced by avant-gardism in the West but also exerting an influence of its own by virtue of the innovative styles that emerged within it, such as Suprematism and Constructivism. Peremen held a series of exhibitions in Tel Aviv to advance his ideas, and Tagger participated in the first, in 1920, and again in 1922 and 1923. She also took part in exhibitions held in the Citadel of David in Jerusalem.

For a native-born artist like Tagger, with no prior exposure to European artistic influences, it was quite difficult learn about the innovations of modern art. In the few art books available locally, most reproductions were printed in black and white. Art postcards were of a poor quality and did not do justice to the colorfulness that played such an important role in the works of the Impressionists, the Post-Impressionists, the Cubists, and the Expressionists. World War I, too, cut Erez Israel off from the western world. The Pereman collection introduced something of the avant-garde spirit, but indirectly, via the works of Russian artists, mainly from Odessa, who had been influenced by international artists such as Gauguin, Matisse, Derain, Falk, Altman, Larionov, and Goncharova. In order to acquaint themselves directly with new trends in modern art, artists from Erez Israel had to go abroad. Indeed, after the war ended, numerous artists (including many women) began making the journey to Paris, then one of the most important centers of modern art.

Travel to Paris

At the end of 1923, Sionah Tagger, too, went to Paris, where, on Constantinovsky’s recommendation, she studied with painter André Lhote and, in 1925, exhibited her own art in the Salon des Indépendants. Lhote, known in those days as a teacher and theoretician, belonged to the Cubist Section d’Or. Tagger was influenced in Paris by Cubism and Futurism, but these influences in her work remained external and formal. She was not interested in their ideas and worldviews. Even after her studies with Lhote, the influence of the Cubist style in Tagger’s art did not go beyond the integration of structural geometric shapes into her paintings. Tagger said she sought a way to integrate the cultures of West and East into a single, Mediterranean culture, and that her studies in Paris helped her clean her work of superfluous details, a quality that characterizes her paintings from the 1920s on, especially her portraits.

Upon her return to Erez Israel in 1925, Tagger took part in the three exhibitions of “modern artists” held in HaOhel Theater in 1926, 1927, and 1928, which were considered of foundational significance in the development of modern Israeli art and in the transfer of the artistic center to Tel Aviv. On her second visit to Paris in 1931, Tagger came more under the influence of Andrée Derain, whose call for a return to realism inspired her to create more detailed and elaborate paintings.

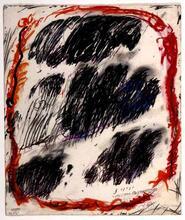

Tagger returned again to Paris in 1950. In 1951, she purchased a house in Safed, to which she returned every summer to paint and to exhibit her works. She became part of that city’s community of artists, with its lively social life of parties, promenades around the city, and conversations about art. From the 1960s on, Tagger began painting on glass and Perspex, influenced by the Arab paintings on glass she had seen in her childhood in the Arab barbershops of Jaffa. It was the colors in these paintings, she said, that held the most fascination for her; she would start with blobs of color, which gradually turned into shapes. The subjects of these paintings, executed in a naïve style, were mostly traditional—the tablets of the Ten Commandments, a Booth erected for residence during the holiday of Sukkot.sukkah, the Holiday held on the 14th day of the Hebrew month of Adar (on the 15th day in Jerusalem) to commemorate the deliverance of the Jewish people in the Persian empire from a plot to eradicate them.Purimfestival, a lulav.

Legacy

Tagger held over 40 solo exhibitions, partly because she had to make her living from the sale of her works, and she participated in numerous group exhibitions in Israel and abroad. She was awarded the Dizengoff Prize in 1937 and represented Israel in the 1948 Venice Biennale. The Tel Aviv Museum held a retrospective exhibition of her work in its Helena Rubinstein Pavilion in 1961, and in 1977 she was honored as a “Distinguished Citizen of Tel Aviv.” Two more large retrospective exhibitions of her paintings were held after her death on June 16, 1988, at the Open Museum in Tefen in 1990 and again at the Tel Aviv Museum in 2003. Notably for a woman artist, Tagger was not consigned to oblivion and did not disappear from the historiography of Israeli art. The large retrospective exhibition in 2003 brought her renewed admiration and exposed a younger generation to her work. Today she is considered one of the best-known Israeli women artists.

Ballas, Gila. "The Peremen Collection and the Beginning of Modernism in Israeli Painting." In From Peremen Collection through the Tel Aviv Museum 1920-32. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 2002.

Ballas, Gila. "Eretz Israel Painters in the Twenties and Cubism.” In The Twenties in Israeli Art. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 1982.

Ofrat, Gideon. "The Glass Painting of Sionah Tagger." In Sionah Tagger Album. Massada, 1981

Rubin, Carmela. Sionah Tagger, Retrospective. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 2003.

Shva, Shlomo. "Painted Tel Aviv." In Tel Aviv in its Early Days 1909-1934. Idan, 1984.

Shva, Shlomo. "The Orient Blew in Her Back.” Sionah Tagger Retrospective !1900-1988). Tefen: The Open Museum, 1990.