Art During the Holocaust

During the Holocaust, a number of women were able to create art while in concentration camps. While some painted and drew clandestinely, others were commissioned by Nazis to create works in exchange for food. In their works women artists combined elements such as idealization, realism, humor, satire, and irony, which bear witness to their desire to escape the world in which they found themselves. At the same time, their paintings and drawings reveal how they maintained their humanity and sensitivity despite the appalling conditions in which they lived. Common subjects and imagery include communal life, hygiene and sanitation, barbed wire fences, and food. Many of the works produced were documentary in nature and concerned with commemoration of both the artists’ situation and with memorializing the works’ subjects.

It is now generally considered that while men and women shared the same fate and their daily existence in the internment and concentration camps was more or less similar, differences between the sexes did exist. Such differences are reflected in the works of art produced in the camps. In general, women were constantly trying to recreate the world of normality—they engaged in cleaning, washing, and cooking, endeavoring to carry on their traditional role as homemakers. Cleaning their barracks served as a way of maintaining connection with their past life, a kind of therapy that gave them a feeling of control over the tiny space they had been allotted. It also served to reduce the risk of infection and outbreaks of disease. Despite the lack of water and sanitary conditions, the women, more than the men, made an effort to look clean and as attractive as possible in the grim misery of their surroundings.

Communal Life

Men and women inmates in the camps were confronted with similar problems—being imprisoned for an unknown period of time, being cut off from one’s familiar surroundings and one’s previous way of life, losing one’s sense of identity, living in crowded conditions with very little privacy, lack of food and appalling hygienic conditions. Yet art created in the camps reveals significant differences between the sexes and their ways of coping with these issues.

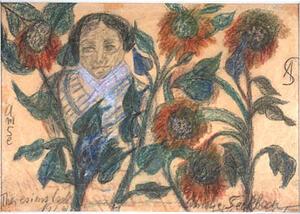

The communal life that the female prisoners were subjected to meant living not only in extremely crowded conditions but also without any privacy. The feeling of suffocation and the lack of private space is depicted by Malva Schaleck in paintings she produced in Theresienstadt. Schaleck, who had established her reputation as an artist in Vienna, returned to Czechoslovakia following the Anschluss (March 13, 1938) and lived there until her internment in February 1942.

In many of the paintings Schaleck produced in Theresienstad, she depicted the activity, or lack of it, in the women’s quarters. Sometimes she drew the interior as crowded and claustrophobic, with women and children lying or sitting on the triple-layered bunks, surrounded by bundles and suitcases. In other works she portrayed a woman, or a few women, sitting on the bed, knitting, reading, or lying down and resting in a tidy, almost homey room. Alongside kitchen utensils—pots and pans, ladles and bowls—she painted washing lines with washing on them and hooks on a wall with clothes, handbags, or other women’s accessories hanging on them. One might expect these interiors to give a feeling of warmth, but in fact they create considerable tension between the extreme order and feminine tidiness and the figures themselves, who, despite the activities in which they are engaged, seem weary and void of feeling.

Similar motifs can be seen in the drawings and watercolors produced by Emmy Falck-Ettlinger in the camp at Gurs in southern France. She was one of the Jews who were torn without warning from their homes in Baden and Pfalz in Germany and in October 1940 sent to various French camps. Falck-Ettlinger, then aged fifty-eight and suffering from cancer, had to adapt to the collective living of prison life, which was so totally different from the bourgeois life she had led until her abrupt internment. The paintings she produced in Gurs show interiors characterized by extreme order and cleanliness. She painted an elderly seated woman, her hair tied back neatly, deep in melancholy thought, against a background of clothes on hooks, kitchen utensils, and personal items such as towels and an umbrella. This painting, like similar ones, gives a feeling of desolation and emptiness which even the domesticity of the interior cannot dispel.

Drancy was a camp on the outskirts of Paris from which most of the internees in the French camps were deported to Auschwitz. In December 1942, the artist Jeanne Lévy was imprisoned there. In a number of watercolors she painted in the camp, such as Dormitory and The Kitchen, she depicted tidy and organized interiors. In The Kitchen she shows an elderly woman, neatly dressed and wearing an apron, sitting by a stove, while another woman seen from the back is seated by a dining-table full of day-to-day domestic items. The atmosphere is one of life and activity. The feminine touch in these pictures bears moving witness to Lévy’s desire to create a feeling of intimacy, warmth, and domesticity in a place known primarily for heartbreaking scenes of deportations to the death camps, one of which included Jane Lévy herself.

These women produced their paintings in different camps and at different times—Emmy Falck-Ettlinger’s paintings are from 1940–1941, before the deportations began, while Schaleck and Levy’s paintings date from 1942–1944, when the deportations to the death camps were taking place. Nevertheless, the common features that characterize their work can be explained. In their depiction of daily life in the camp they presented an inner truth, in which the external merely reflected their mental and emotional state.

Hygiene and Sanitation

Even the most intimate physical acts were carried out in public in the camps. In the women’s camp Rieucros, in southern France, the female inmates struggled with these day-to-day difficulties. Sylta Busse-Reismann produced a series of paintings showing the life of the inmates, including having to wash outdoors and using a chamber pot to wash their hair. Although these are nude scenes, Busse-Reismann does not reveal the identity of the inmates; she uses various devices, such as depicting one inmate from the back or hiding the eyes of an inmate portrayed frontally, so as not to disclose the identities of the women forced to perform intimate activities in public. Despite her satirical humor, the extreme deprivation of the women inmates is clear. The artists Lou Albert-Lazard (Mabull) and Lili Rilik-Andrieux, who were interned in Gurs, both portrayed the rituals of washing, laundry, and hair-washing in the women’s barracks—each from her own different point of view, yet each of them attesting to the importance of these mundane, banal activities in their new surroundings.

Portrayals of the ritual of washing and bathing are not new in the history of art. However, the women artists in the camps did not paint these scenes as genre paintings, nor were they merely observers, for they shared the same experiences themselves. For them, depicting scenes of bathing was a reflection of a reality in which washing was an act fraught with obstacles.

If having a wash was a complex feat, going to the toilet was no easier. In many of the camps the toilets had no divisions between them. The enforced public exposure of going to the toilet was most disturbing for the inmates. Hence the installment of toilets in a camp was a major event in the eyes of the prisoners. In Rieucros the women celebrated the installment of a new toilet building by putting on a sketch written especially for the occasion, Clochemerle in Rieucros (Clochemerle à Rieucros), as was fitting for the “inauguration ceremony” of such an important and essential public building.

The subject of toilets has little aesthetic appeal and is not a common topic in traditional art. Yet it was a constant motif in the art of the camps. Getting used to these conditions, with no privacy, not even when taking care of basic bodily excretions, is recorded in the works of a number of female artists. Hanna Schramm produced several amateur drawings, not without humor, depicting the experience of going to the toilet. Liesel Felsenthal, who was only sixteen when she was interned in Gurs, produced an illustrated diary entitled Gurs, a kind of Book of Hours, presenting a day in the life of the camp, in which a special entry is devoted to the use of the toilet.

By drawing this subject, the artists condemned the bestiality that was imposed on the women when they were forced to relieve themselves in public, an act that in civilized societies is performed behind closed doors. These works do not depict torture or violence. What is presented is the humiliation that derived mainly from indifference and thoughtlessness.

The Barbed-Wire Fence

There are scholars who see an element of documentation in all Holocaust art, even if that was not the artist’s intent. This is supported by the fact that the inmates of the various camps painted and drew similar subjects reflecting their daily existence such as the barbed-wire fence, which, above all, symbolized their being in an enclosed space, isolated and cut off from the society of which they had been part. Both men and women artists portrayed this symbol of the barrier between them and the outside world. Yet the work of women artists frequently reveals a different attitude towards the barbed wire fence. Hanna Schramm in Gurs, with considerable humor and irony, drew pictures of washing hung out to dry on the barbed-wire fences. Lou Albert-Lazard, in the same camp, painted Three Women Sitting by a Barbed-Wire Fence at Sunset. In the background of this picture are the Pyrenees, encircling the camp in all directions. The women are sitting by the fence, which looks as if it is made of fine threads wrapped around the figures. The three inmates are sunk in their own thoughts and the symbol of captivity, the barbed wire, does not look particularly sharp or strong. It looks delicate, like the strands of a spider’s web, yet it completely envelops the women, pinning them down. The image is one of an animal caught in netting that seems very fine yet nevertheless imprisons them. The sense of being trapped is no less threatening and restraining.

Food

One of the central problems for men and women inmates alike was starvation. Emmy Falck-Ettlinger portrays women making toast in the barracks at Gurs, while in another picture in the same camp she shows a woman clutching a whole loaf to her bosom, as a mother holds her infant. Malva Schaleck drew women peeling vegetables in Theresienstadt. Searching for food was a major preoccupation for the women, whether in reality or in their imagination. One of the ways they tried to forget their gnawing hunger was by exchanging recipes, which allowed them a kind of return to their normal life at home.

Ewa Gabanyi, who was interned in Auschwitz on April 3, 1942, produced a Memories Calendar (Kalendarz wspomnie?), comprising twenty-two small drawings (18 x 10 cm.). The pictures in this calendar are mostly theatrical and fantastic—surrealistic dances and balls, elaborate costumes, weird animals and exotic scenery. One picture stands out as completely different: she depicts a woman prisoner in her striped dress eating soup, with the inscription First soup in the camp (Zjada pierwsw? Zoupk? Lagrow?). Because of the importance of food in the lives of the inmates, and the fact that this picture is dated April 27, 1942, we know that the artist did not receive her first hot meal until three weeks after her arrival in Auschwitz. Thus a picture that seemed completely naturalistic turns out to have a somewhat surrealistic aspect in the world of the camps.

The Imagination

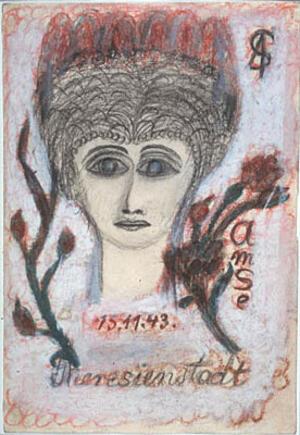

Like other artists, Ewa Gabanyi was able to escape from the harsh reality of the camps on the wings of fantasy. This escapism can be seen in the paintings of Amalie Seckbach produced in Theresienstadt. Seckbach, who was an artist and an art collector focusing mainly on Far Eastern art, had been able to continue her normal, comfortable lifestyle in Frankfurt even after the rise of the Nazis. However, in September 1942 she was sent to Theresienstadt where, in a state of poor health and fatigue, she painted watercolors that at first glance seem to have no connection with the reality around her. Her paintings transcend time and place. She painted beauty in a world of suffering and death—flowers, fantastic landscapes, and surrealistic portraits. She included motifs derived from Japanese art, connecting to her previous life and maintaining her identity as a cultured and creative person instead of a prisoner. The painting Young woman with crown among flowers depicts a young woman with Asian features, big dark eyes, and a crown on her elegantly gathered wavy hair. Stems of flowers frame her face on both sides. On her neck, where one might expect to see a jewel, Seckbach has written in large, bold, red numbers the date of the painting—15.11.43—and at the bottom, at an imaginary point connecting the flower stems, the word Terezin appears. This painting is an example of a work that combines all the worlds in which Seckbach was living. On the one hand, she clings to the cultural heritage she had known for so many years, as can be seen in the initialized signatures she uses—AS and AMSE—according to accepted Japanese practice. By doing this, and by portraying a regal Asian figure, like a princess from the legends of the Arabian Nights, she endeavors to escape to other worlds. On the other hand, the lower part of the picture grounds her firmly in reality. In addition to the elements of fantasy this painting, like many others by camp artists, contains historical documentation. Schaleck records with great care and accuracy the time (November 1943) and place (Terezin) of its creation. The tension between these two elements—transcendence and reality—produced the dualism of Seckbach’s existence, in which the imagination, despite its infinite possibilities, cannot completely erase present reality.

The Artist as "Privileged"

Portraits

There was often a feeling in the camps that artists enjoyed a certain immunity and that their fate would not be the same as that of the other prisoners. The idea that artistic talent represented an insurance policy can be illustrated in various ways.

Charlotte Buresova was interned in Theresienstadt in July 1942 and put to work in the artists’ workshop (Zeichenstube), where she was commissioned to copy works by famous classical painters. A German officer, highly impressed with her artistic talent, commissioned a painting of the Virgin Mary. He told her not to finish the painting, because as long as she was working on it she would not be deported—and he kept his promise.

In addition to the commissioned paintings that helped her survive, Buresova also did pen and crayon drawings, including portraits of children and her musical friend Gideon Klein. She also drew dancers, giving them, as she put it, grace and beauty in contrast to the horror, hunger and pain they were all suffering.

Testimony by Halina Olomucki also bears witness to the notion that artists enjoyed a better fate than other prisoners. She painted and drew from an early age, continuing to do so in the Warsaw ghetto, where she was sent when she was eighteen years old. Later she was interned in the camp at Majdanek where, in a state of near collapse, her artistic talent came to her assistance. She was commissioned by the head of the block to decorate the walls of the building. In return she received improved food rations, which helped her recover. She used some of the materials she was given officially to paint her fellow women inmates clandestinely. From Majdanek she was transferred to Auschwitz-Birkenau and there too she was a commissioned artist for the Germans. For this she received more substantial food, which helped her to survive. Her fellow inmates begged her to paint their portraits or those of their daughters, in the belief that this might be their last chance to be commemorated. They were convinced that Olomucki, as an artist, would survive, basing their belief on the privileges she received. They asked her to take the portraits with her to the outside world when she was liberated.

Olomucki’s portraits of women inmates, more than anything else, reflect her own inner world. They seem to lack physical substance, as if only a thin shell protects them and defines their fragile features. This is how they appear whether they are alone or in the company of children. The pictures give the feeling they are floating airily beyond reality.

It seems, however, that this artistic immunity did not always help. According to the testimony of a Czech journalist, the artist Malva Schaleck was transferred from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz because of her artistic talent. She refused to paint the portrait of a collaborator and as punishment she was included in the next deportation list, in May 1944.

Many of the portraits Schaleck produced in Theresienstadt were commissioned and she received food in payment. In order to attract more clients she did some publicity portraits, in which the subjects were highly embellished. There is a significant difference between her commissioned portraits and the works not produced in order to make a living. One example is the Portrait of the Child Hans Roth, painted at the request of his parents. Despite his rosy cheeks, neatly combed hair and smart appearance, the child’s eyes have a look of sadness and maturity beyond his years. Two portraits of women, Mrs. Brodeckie and Mrs. Goldmann, were done in the best tradition of portrait painting of the time. The portraits show handsome, well-groomed women, revealing nothing about the location or the circumstances in which the portraits were painted. Just one thing stands out as unusual—Schaleck has written the subject’s name. In this way the portrait is not only a commissioned work but also a commemoration of the individual.

The phenomenon of commemoration through portraits was extremely common in the art of the Holocaust; portraits comprise one quarter of all paintings and drawings produced in the camps. Portraiture had almost magical powers, for it granted the subjects a feeling of permanency, in contrast to the extreme fragility of their actual existence. The portraits are sometimes spontaneous, expressing a close relationship between artist and model, while others are clearly embellished. Many portraits were commissioned in order to be sent home to raise the morale of family members by showing that the subject was alive and well. In these portraits the artist naturally tended to embellish reality, hardly showing the deplorable state of the subjects, in order to prevent suffering among relatives. Sometimes enhancing reality was the artist’s desire.

Portraiture enabled both the artist and the subject to leave their personal stamp, proof of their existence as individuals at a time when life was so tenuous.

Art as Documentation

Holocaust art is often considered documentary art, produced, at least partially, in order to record the indescribable for posterity. Documentation is a major element in the work of Esther Lurie. Lurie, who had earned a considerable reputation as an artist before the war, was sent to the Kovno ghetto, where she at first drew out of interest in the new situation, since everything that was happening was so completely different from her previous way of life. She felt that she must record this new existence or at least make sketches of it. Later, when the Council of Elders (Ältestenrat) realized her talent, they asked her to document everything that was happening in the ghetto. They recognized the importance of drawings as both art and documentary evidence.

So, as far as she was able, Lurie recorded life in the ghetto—men, women, children, old people, scenes of nature and scenes of human hardship. When the ghetto was destroyed in July 1944, Lurie was sent to the concentration camp at Stutthof and then transferred to a labor camp at Leibitz. Although no longer an official artist, she continued her task of documentation, sometimes for herself and at other times for commission. In the latter cases she could barter her art for food, as happened in other camps during this time.

In their works women artists combine many different elements, such as idealization, realism, humor, satire, and irony, which bear witness to their desire to escape the world in which they found themselves. At the same time, their paintings and drawings reveal how they maintained their humanity and sensitivity despite the appalling conditions in which they lived.

Artists

Lou Albert-Lazard (Mabull) (1885–1969)

Lou Albert-Lazard was a Jewish artist born in Metz, daughter of a banking family. From 1908 to1914 she studied art in Munich and Paris, becoming friendly with the artist Fernand Léger (1881–1955). In 1909, she married Eugene Albert and gave birth to a daughter. Her marriage foundered because of her close relationship with the poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926), with whom she lived in Munich and Vienna during the years 1914–1916. From 1916 to 1918 she lived in Switzerland, then moved to Berlin where she was close to an avant garde group of artists known as the Novembergruppe. She did mainly drawings and etchings of portraits of her friends. In 1928, she settled permanently in Paris, becoming part of the artistic milieu of Montparnasse. Albert-Lazard went on several journeys with her daughter, visiting North Africa, India, Tibet, and other places. Drawings and watercolors inspired by her journeys were exhibited in 1939.

In May 1940, she and her daughter were interned in Gurs. Surprisingly, she was released from the camp in August 1940. She did drawings and watercolors of the women inmates of the camp, who were her models, showing them in various scenes of camp life. She used to wander around the camp with a sketchpad in her hand, wearing a wide-brimmed hat and a colorful scarf, and was considered eccentric. After her release, she returned to Paris and in the 1950s resumed her travels with her daughter by caravan, recording her impressions in watercolors and lithographs. She died in Paris in July 1969.

Irène Awret (b. 1921)

Irène Awret was born to a Jewish family in Berlin, the youngest of three children. In 1937 she was forced to leave high school because of the antisemitic decrees in Nazi Germany. Since she could not continue her regular studies, her father sent her to study drawing, painting, and restoration with a Jewish artist. In 1939, the situation deteriorated even further—her father was dismissed from his job and the family was forced to leave their home. As a result, her father sent Awret and her sister to Belgium, with the help of smugglers. Awret worked as a maid for a Dutch Jewish family and studied art at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts (Académie Royal des Beaux-Arts) in Antwerp. A few months later her father joined her and her financial situation eased. She left her job and studied full time. During this period Awret did restoration work and commissioned portraits.

The beginning of World War II (September 1939) coincided with the beginning of her studies at the art academy and for a few months her life did not change. Only with the German invasion of Belgium (May 10, 1940) did things worsen. Awret found a hiding place on a farm in Waterloo with a Jewish family. In January 1943, she was forced to return to Brussels, where she lived with a false identity card, according to which she was a married woman with two children.

An informer reported her to the Gestapo and she was arrested. Awret took with her a bag containing food, paper, and drawing materials. While she was detained in the Gestapo cellars in Brussels she drew Palm of My Hand because she had no other object to draw. Irène Awret was interrogated to make her reveal the hiding place of her father (who was also in Brussels), but she refused to cooperate. The torture was intensified and she was taken to be interrogated by Erdmann, the head of the Gestapo in Brussels. When Erdmann saw her sketches, he asked her where she had studied art and halted the interrogation. She was transferred to a narrow cell and then sent to the camp at Malines, where she worked in the leather workshop, decorating brooches. Malines was a transit camp for Auschwitz where people were gathered prior to deportation to the camps in Eastern Europe. When Irène Awret reached Malines, Transport no. 20, which left a week later, was not quite full, but she was not put on it. Her artistic talents became known and she was transferred to the artists’ workshop (Malerstube), where she worked doing graphics for the Germans until the end of the war. In the artists’ workshop she met a Polish Jewish sculptor, Azriel Awret, who later became her husband.

After the war the Awrets immigrated to Israel and set up home in the Artists’ Quarter in Safed, where they continued working. They later divided their time between Israel and the United States. In the art collection at the Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum there are works by Awret from the time she was in the Malines camp. These works of art, which depict various aspects of life in Malines, were donated to the Museum by the artist.

Interview with Dr. Pnina Rosenberg, August-September, 2000; The Museum of Deportation and Resistance, Malin (Mechlen) archive, Belgium.

Charlotte Buresova (1904–1983)

Charlotte Buresova was a Jewish artist born in Prague on November 4, 1904, the only daughter of a tailor. At an early age she already showed signs of artistic talent and her family saw to it that she received an extensive education in the arts—painting, playing the piano, and French. She painted portraits, still life, and flowers. She did not exhibit her works, preferring to give them to her friends as gifts. Buresova was married young to a non-Jewish lawyer and gave birth to a son, but when the Germans occupied Czechoslovakia she divorced her husband in order to prevent the decrees against Jews from affecting her family.

In 1941, she was forced to leave her home, which had been confiscated by the Germans. In July 1942, she was imprisoned in Theresienstadt and put to work in a specialized workshop, where she painted tiles for the Germans. Subsequently Buresova was sent to the artists’ workshop where, at the instruction of the Germans, she painted copies of works by classical masters such as Rubens and Rembrandt. Works that were not commissioned by the Germans she did in pencil, crayon, chalk, watercolors, and, occasionally, oils. The subjects of her paintings, some of which depicted the extensive artistic and cultural activity in Theresienstadt, included portraits of children and of her musician friends, as well as flowers and dancers. Buresova explained that she wanted to portray the dancers’ grace and beauty in contrast to the horror, hunger, and pain they were all suffering.

Buresova mentioned that there were different points of view among the artists in Theresienstadt. While Jo Spier, a Dutch artist, believed that artists must paint even when cannons are firing, Buresova disagreed with him. She contended that there were times when she could no longer paint, but Spier urged her not to give in and to continue creating. She affirmed that out of all her works those that were produced in Theresienstadt were the most sincere and direct because there was nobody who could influence her.

Buresova’s situation in Theresienstadt was better than that of most of the other inmates. She worked all the time, had a room of her own, possessed books, and was in touch with her friends. In an interview with Miriam Novitch, the first curator of the Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum, Buresova said that the unknown tomorrow was more terrible than hunger and dreadful housing. Buresova was terrified of the deportations to the East, since no one knew who would go next.

It was a German officer who, greatly impressed by Buresova’s artistic talent, prevented her deportation. He asked her to do a painting of the Virgin Mary, which she painted with a tear in the Madonna’s eye. The officer was very impressed when he saw it and told her not to complete the painting. As long as she was working on it, she would not be deported to the East. Three days before the liberation of Theresienstadt, Buresova, along with a small number of inmates, succeeded in escaping and she returned to Prague in the Swedish ambassador’s car.

Buresova lived in Prague until her death in 1983. Her son, who lives in Prague, became a doctor. Some of her post-war works are based on her memories of Theresienstadt. She donated a number of her works from the camp to the art collection of the Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum.

Sylta Busse-Reismann (1906–1989)

Born in Westerland in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, Busse-Reismann was a theater costume and set designer. Her father owned a hotel, while her mother was an artist. At the age of twenty she went to Berlin to study at the Academy of Art. In 1932 she moved to Moscow with her husband, Jánosz Reismann, a Hungarian journalist. In Moscow she designed theater sets and appeared in German-language plays put on by immigrant theater companies. She also designed costumes and sets for the Bolshoi opera company. In 1938, with the increasingly harsh Stalinist policies regarding foreigners, she and her husband moved to Paris, where she continued her artistic and theatrical activities, primarily in German immigrant theater companies. In February 1940 she was arrested and sent to the women’s camp of Rieucros, where she spent part of her internment (April–May 1940) in the camp infirmary. She recorded her time in the camp in a series of drawings depicting daily life in the camp, as well as her fellow inmates. On November 13, 1940, she escaped from the camp with the assistance of her husband, who was living clandestinely in Paris.

Busse-Reismann returned illegally to Schleswig-Holstein, where she was hospitalized in a sanatorium until the end of the war because she had contracted tuberculosis while in the camp. After the war she married set designer Hans Ulrich Schmückle and worked together with him in various theaters in East and West Germany, Austria, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, Britain, and Switzerland. She died in Augsburg in March 1989. Her works from the period of her internment are held in the Academy of Fine Arts, Berlin-Brandenburg.

Emmy Falck-Ettlinger (1882–1960)

Emmy Falck-Ettlinger was born in Lübeck (Germany), studied art in Berlin, and after her marriage moved to Karlsruhe in Baden-Würtemberg. In October 1940, with the deportation of Jews from Baden and Pfalz, she was interned in Gurs. She suffered from breast cancer and in 1941 was transferred to a special center founded by Abbé Alexandre Glasberg (1902–1981). During the year 1942 she was allowed to move to Switzerland, where she lived with her son. In 1950 she immigrated to Israel, joining her daughter who was a member of A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.Kibbutz Bet ha-Shittah. She died in 1960.

Her drawings from Gurs portray emptiness and loneliness. She drew the cemetery at Gurs, where over a thousand inmates were buried, most of whom had been deported from Germany. She donated her works to the art collection of the Ghetto Fighters’ House.

Liesel Felsenthal (b. 1924)

Liesel Felsenthal was born in Mannheim and lived there until October 1940 when, with the expulsion of the Jews from Baden and Pfalz, she was interned in the camp at Gurs. Felsenthal, who was sixteen years old when she came to the camp, produced a booklet of paintings titled Gurs 1941, a book of hours depicting a day in the life of the camp. After the war Felsenthal and her husband, Walter Basinzki, who was also interned in Gurs, immigrated to Israel. Gurs 1941 is part of the collection of the Leo Baeck Institute, New York.

Ewa Gabanyi (b. 1918)

Little is known about this artist, who was born to a Jewish family in Czechoslovakia on December 17, 1918, and on April 3, 1942, was deported to Auschwitz, where she became Prisoner No. 4739. She was assigned to a “plant unit” (Pflanzenzucht) headed by Obersturmführer Joachim Cesar, an agronomist who had been appointed to set up an experimental scientific unit to do research on a type of dandelion that provided a white latex used in the production of synthetic rubber. Her job was to draw the fauna. Alongside this official activity, Gabanyi also contributed her talents to the underground activity in the camp. She had access to art materials, which she used to create scenery for a play performed clandestinely by the prisoners on New Year’s Eve 1942. She also produced a Calendar of Memories, consisting of twenty-two small paintings (10 x 18cm.) done in ink and watercolors. The paintings are extremely theatrical and fantastic, yet some of the scenes and figures were clearly inspired by daily life in the camp. The Calendar of Memories is kept in the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.

Jeanne Lévy (1894–1944?)

Lévy was born in Paris on September 28, 1894, to an Orthodox Jewish family from Alsace. Her artistic talent was recognized when she was still very young and at the age of eighteen she went to the Academy of Decorative Arts (Académie des Arts Décoratifs) to study painting. Subsequently she specialized in ceramics, working for many years for the porcelain firm Manufacture Nationale de Sèvres. In 1932 she held an exhibition at the International Fair in Tel Aviv.

Lévy took an active part in artistic life in Paris. Her paintings were shown at the Salon des Artistes-Décorateurs, Salon des Tuileries and Salon d’Automne. In 1931, she exhibited in the Parisian Exposition Colonial Internationale in the The Land of IsraelErez Israel Pavilion.

After the German invasion of France Lévy was dismissed from her work at the porcelain firm because she was Jewish. On November 27, 1942, she was arrested and imprisoned in the La Santé prison, from where she was transferred to Drancy camp, near Paris. There she painted delicate watercolors of daily life in Drancy which reflect the efforts made by the inmates to maintain a feeling of home even in the camp known as the waiting room for Auschwitz, despite the desperate feeling of uncertainty that resulted from the frequent deportations. On July 31, 1943 Lévy and her brother Albert were deported to Auschwitz.

Lévy’s works are kept in the archives of the Centre de Documentation Juive Contemporaine, Paris.

Esther Lurie (1913–1998)

The daughter of a religious Jewish family with five children, Esther Lurie was born in Liepaja, Latvia, which her family was forced to leave during World War I because the city served as a military port. In 1917, the family returned to Riga, where Esther Lurie graduated from the Ezra Gymnasium. She developed her artistic talent from the age of fifteen by studying with various teachers. In the years 1931–1934 she studied set design at the Institute of Decorative Arts (Institut des Arts Décoratifs) in Brussels and drawing at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts (Académie Royal des Beaux-Arts) in Antwerp.

In 1934 Lurie immigrated to Palestine with most of her family. She designed sets for the Hebrew Theater in Tel Aviv. When events limited theatrical activity in Palestine, she devoted herself to drawing, especially portraits. In 1938 she won the prestigious Dizengoff Prize for Drawing for her work The The Land of IsraelErez Israel Orchestra, which was exhibited in the Tel Aviv Museum.

In 1939 Lurie went to Europe to pursue her studies, visiting France and studying at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts (Académie Royal des Beaux-Arts) in Antwerp. In Riga she exhibited her works in an exhibition that took place in the Painters’ Association House. In 1940 she had an exhibition in Kovno in the Royal Opera House. Her works were received with great acclaim and some of them were purchased by local Jewish institutions as well as by the Kovno State Museum. After the German occupation her works were confiscated, having been defined as Jewish art.

World War II broke out while she was in Lithuania, and during the German occupation she was imprisoned in the Kovno ghetto (1941–1944), where she at once began to sketch the scenes of the new reality. The members of the Council of Elders (Ältestenrat), who learned of her talent after seeing one of her paintings, asked her to document everything that was happening in the ghetto. Her works were displayed in an exhibition held in the ghetto.

The Germans also showed interest in Lurie’s artistic talent and she painted pictures commissioned by the German commanders. Lurie, who drew everywhere in the ghetto, received special permission from the German commander to draw in the pottery workshop. While she was there, she asked the potters to prepare a number of jars for her in which she could conceal her works if the situation worsened. After the deportation of March 26, 1943, the artist hid her collection of drawings—approximately two hundred drawings and watercolors of 25 x 35cm.—in the large jars prepared in advance. Some of the works were photographed for the ghetto’s clandestine archives.

In July 1944, as the Red Army approached Lithuania, the ghetto was liquidated and those remaining in it were transferred to concentration camps and forced labor camps in Germany. Esther Lurie was deported and her hidden works were left behind. Later it was found that some of her drawings had survived along with the archives of the Council of Elders. Avraham Tory-Golob succeeded in rescuing and bringing to Israel eleven sketches and several watercolors, as well as twenty photographs of her works. She was unable to discover what happened to the rest of her works.

Up to the end of July 1944, Lurie, along with the other women from the ghetto, was held in the Stutthof concentration camp, where she was separated from her sister, with whom she had been together through the whole ghetto period. Her sister and her young son were deported to Auschwitz, from which they never returned. In Stutthof Lurie continued to receive commissions and more than once her art served as barter for food. In August 1944 she was transferred to Leibitz, where she painted portraits of several inmates.

Esther Lurie was liberated by the Red Army on January 21, 1945. In March 1945, she reached a camp in Italy, where she met Jewish soldiers from Palestine who were serving in the British army. One of them, the artist Menahem Shemi, organized an exhibition of drawings from the camps and brought about the publication of the booklet Jewesses in Slavery, which contained drawings by Lurie from Stutthof and Leibitz.

Lurie reached Palestine in July 1945. In 1946 she was awarded the Dizengoff Prize for her sketch Young Woman with Yellow Star, done in the Kovno ghetto. She married, raised a family, and continued to paint and exhibit in group and solo exhibitions in Israel and abroad.

During the Eichmann trial, which took place in Jerusalem in 1961, Lurie’s works from the time of World War II served as testimony, thereby gaining official approval by the Supreme Court for the documentary value of her sketches and watercolors.

Lurie died in Tel Aviv in 1998. Part of her works from the period of the Holocaust are in the collection of the Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum, to which they were donated by the artist. Her works of art can also be found in the Yad Vashem collection in Jerusalem and in private collections.

Halina Olomucki (b. 1919)

Halina Olomucki, née Olszewski, was born in Warsaw on November 24, 1919. Her father Andrzej, a newspaper distributor, died when she was five years old. Her mother, Margarita-Hadassa, became the provider for the family, which, in addition to Halina, included her older brother Mono (b. 1909). Olomucki, a member of a non-observant Jewish family, went to a Yiddish-speaking elementary school in the city of her birth and then to a high school. She showed her artistic talent from an early age.

Eighteen years old when World War II broke out, Olomucki was sent to the eastern side of the Warsaw ghetto, where she immediately began to draw and paint. Halina Olomucki told of the great strength she drew from her creative artistic work; it was like a need or an urge that could not be overcome.

Olomucki worked outside the ghetto and smuggled in food for her family. However, her main purpose was to paint. While she was outside the ghetto, among non-Jews, she met a man to whom she gave her drawings from the ghetto.

From the Warsaw ghetto Olomucki was deported to Majdanek. There she was separated from her mother, who was sent to her death, a fate that was also supposed to have been hers. As the result of a momentary confusion, which distracted the guards’ attention, she escaped from the queue and joined another group of women who were carrying pails of water and food. Despite her extreme thinness, she succeeded in carrying a pail of water and looking as if she belonged to them. In the camp she was required to draw slogans on the walls and to decorate them. She did complex and colorful paintings for which she received praise from the camp administration and extra food. Olomucki used some of the material she received officially for her own use, and began to do drawings clandestinely of the women who were imprisoned with her. She hid the drawings in as many hiding places as she could find.

From Majdanek Olomucki was sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau as Prisoner No. 48652. Some of the prisoners there were employed in the textile industry, but as Olomucki had no talents in that area she was asked to continue painting, receiving richer food—bread and cheese—as payment for her work. Olomucki stated that this is what made it possible for her to survive. Olomucki stated that the faces of the prisoners were inscribed so deeply in her memory that she could draw them even years later.

From Auschwitz she set out on the Death March, which began on January 18, 1945. Olomucki reached the Ravensbrück camp and from there was transferred to the Neustadt camp, where she was liberated by the Allies. Her mother and her brother perished in the Holocaust. After the war she returned to Warsaw, where she married an architect, Boleslan Olomucki. Later she moved to Łódź, where she studied at the art academy. In 1957, she emigrated to France and lived in Paris, from where she immigrated to Israel in 1972.

Immediately after the war, from 1945 to 1947, Olomucki unceasingly drew from her memories of the period, as she was aware of the documentary value of these works. In the 1960s she showed her works in many exhibitions in Paris and London.

Olomucki’s works from the Holocaust period, or those that were done under its influence, were donated to the Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum art collection by the artist. Others can be found in Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, The Musée d’histoire contemporaine, Paris, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, and the Auschwitz Museum.

Lili Rilik-Andrieux (1914–1996)

Lili Rilik-Andrieux, née Abraham, was born in Berlin to a wealthy, cultured family. She studied art in Berlin from 1933 to 1937 and in 1938 went to Paris to continue her studies at the Académie Ranson.

In May 1940, Rilik-Andrieux was taken to a transit center in Alençon and in June sent to Gurs, where she was held until March 1941. She then moved to the Terminus hotel in Marseille, where women and children were kept under surveillance while waiting for immigration permits. In September 1941, she was interned in Gurs for a second time up to November 1941, when she was returned to the Terminus hotel. There she remained until August 1942. During August and September 1942, along with all the other women and children who had been kept in hotels in Marseille, she was sent to the camp at Les Milles. She contracted typhus and was hospitalized in Aix-en-Provence. After her discharge from hospital she joined the underground.

After the war Rilik-Andrieux remained in Aix-en-Provence until 1946, working as a translator for the American army. In 1946 she went to the United States, and six years later married Ricardo Esther, a Spanish refugee whom she had met in Gurs. In 1981 she settled in San Diego, where she lived until her death in 1996.

Some of her paintings depicting scenes of life in the camp at Gurs are part of the art collection of the Ghetto Fighters’ House, while others are part of the art collection of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, and the Bibliothèque Nationale, Print Department, Paris.

Dora Schaul (1913–2000)

Dora Schaul, née Davidsohn, was born in Berlin to a Jewish merchant family. In 1933 she was dismissed from her job as a clerk because of the Nazi racial decrees. When it became clear that she could not make a living in the changed circumstances, she moved to Amsterdam, where she met Alfred Benjamin-Ben, a communist militant who had escaped from Germany after being held there in a prison camp. In 1934 they went to Paris, where Ben worked as an editor of the communist newspaper, Le Trait d’union, whose purpose was to strengthen the connection between anti-Fascist German immigrants and the French population. While she had previously not been politically active, she became an enthusiastic supporter of the communist party, and took part in distributing information about the activities of the Third Reich.

In September 1939, Schaul was arrested as a Jewish German communist and imprisoned in the Paris prison La Petite-Roquette. In October 1940 she was transferred to Rieucros, where she was interned throughout the entire period of the camp’s existence, up to February 1942. At the same time Ben was held in a labor camp for foreigners not far from Rieucros. He succeeded in visiting the camp and the couple even got married at the town hall in Mende in February 1941.

Schaul played an active part in the cultural and social life of the camp. Although she had never studied art or done any painting before, she recorded life in the camp in colorful drawings and sketches.

In February 1942, together with all the women interned in Rieucros, Schaul was transferred to the Brens camp. With the help of the communists she escaped from the camp on July 14, 1942, six weeks before the deportation of the Polish and Jewish prisoners to the East. Schaul’s name appeared on the lists for deportation. In the summer of 1942 her husband escaped from the labor camp for foreigners and was killed as he tried to cross the Swiss border.

After her escape from the camp Schaul joined the resistance using the assumed identity of Renée Gilbert, a French woman born to a Swiss mother. Until the end of the war she worked in the offices of the Gestapo in Lyon. Schaul passed on essential information, such as the names of SD (the security service of the SS) and Gestapo personnel in Lyon, which were then broadcast on Radio London. In 1946, she returned to (East) Berlin, married Hans Schaul, and worked at the Institut für Marxismus-Leninismus. Schaul died in Berlin in 2000.

Schaul, who published a number of articles about her life in France during World War II, was one of the witnesses at the Klaus Barbie trial in Lyon in 1987.

Hanna Schramm (1896–1978)

Born in Berlin, Schramm was a member of the Social-Democrat Party (SPD), which was banned after Hitler’s rise to power. In 1934, she moved to Paris after being dismissed from her job as a teacher. At the outbreak of war, she was arrested for three months under suspicion of spying. Soon after her release she was detained and held in a number of small camps. From June 9, 1940 to October 29, 1941 she was interned in Gurs.

After the war she settled in Paris, where she lived until her death in 1978. She worked as a journalist, publishing a number of books, including Vivre à Gurs which relates the story of her life in the camp, illustrated with her own drawings. Although she was not a professional artist Schramm produced humorous and ironic drawings of life in Gurs. Her works, which enjoyed great success in the camp, are part of a private collection.

Malva Schaleck (1882–1944)

Schaleck was born in Prague on February 18, 1882, to a wealthy and cultured Jewish family that originally came from Bohemia. She was the youngest of four children. On the ground floor of the building in which the family lived was a large bookshop, which they owned, along with a lending library, a music library (Musik Schaleck), and a furniture store (Möbel Schaleck) in other parts of the city. Her grandfather, Josef, and father, Gustav, took part in the cultural and political activities of the Czech nationalist movement, and the bookshop was a salon for intellectuals, an activity that did not cease even after her father’s sudden death in 1889 and was continued by her mother, Judith (née Wohl). After finishing her secondary education, she moved to Munich, where for a year she studied art at the Women’s Academy (Frauenakademie). She then moved to Vienna, where she opened a studio. While in Vienna, Schaleck acquired a reputation as a portrait artist, the subjects of her paintings being mainly middle- and upper-class Jews.

After the Anschluss (the annexation of Austria to Germany) in March 1938 and the introduction of antisemitic laws by the Nazis, Schaleck fled from Vienna, leaving all her works behind in her studio.

In 1942 Schaleck was transported to Theresienstadt, where she depicted scenes of life in the ghetto. Her works, done in pencil, charcoal, and watercolors, were hidden in the walls of the buildings and discovered after the liberation. They are a faithful testimony to various aspects of the living conditions in the Theresienstadt ghetto-camp.

According to the testimony of a Czech journalist, Malva Schaleck was sent to Auschwitz on May 18, 1944, after refusing to draw a physician who was a collaborator. There she perished. A large number of Schaleck’s works were donated to the Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum by her niece and nephew, Lisa Fittko and Hans Eckstein, and also by David Ziskind and Moshe Knobloch.

Amalie Seckbach (1870–1944)

Seckbach was born in Hungen, near Frankfurt on May 7, 1870, to the Buch family, who were well-to-do Jewish merchants. Her father dealt in agricultural machinery. Seckbach had three older brothers. Seckbach received the education of a girl from a well-to-do family—in addition to reading and writing she also studied piano, singing, painting, and how to run a home. In 1907, she married Max Seckbach, a well-known architect; their marriage produced no children.

During World War I Seckbach, like many other women of her class, volunteered to do welfare work, and received an award from the German Red Cross for her work. After her husband died in 1922 Seckbach felt alone and occupied herself with sculpture, an art form she had taught herself.

In Frankfurt museums Seckbach was exposed to colorful Japanese and Chinese woodcuts. In 1926, she took lessons at the Institute of Chinese Studies at the University of Frankfurt (apparently as an unregistered auditor) and became an expert in the field of Japanese and Chinese woodcuts, as well as a collector. The Seckbach Collection began to be exhibited in well-known German museums and even acquired an international reputation. She also exhibited her own works—small busts—which were displayed alongside her art collection.

In Belgium in 1930 Seckbach met the painter James Ansor (1860–1949), who was very impressed by her work. Together they exhibited at the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, and Seckbach’s work received excellent reviews. At the age of sixty she began to exhibit abroad, mainly in the Salon des Surindépendants in Paris, and her works were highly regarded and praised.

When the Nazis came to power, the artist’s works were confiscated as “degenerate art,” but Seckbach was still able to exhibit for several more years in Germany in the framework of the Jewish Cultural Association (Jüdischen Kulturbundes). Due to her international connections she continued to exhibit abroad—in Madrid, Florence, Paris, Brussels, and Ostende in Belgium. The works of this self-taught artist, who began to paint and sculpt at a relatively advanced age, were exhibited alongside sculptures and pictures by renowned artists such as Marc Chagall (1887–1985) and Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947). In 1936, she was invited to exhibit at the prestigious Art Institute of Chicago.

In 1939 Seckbach was still living in her luxurious eight-room apartment in Frankfurt. In 1941, like the other Jews of Germany, she was forced to wear the yellow badge. Later Seckbach understood the gravity of her situation but her last-minute attempts to get to the United States via Lisbon were unsuccessful.

On September 15, 1942, she was sent to Theresienstadt where she succeeded in producing works of art despite her poor physical condition. Some of her paintings survived and can be found at the Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum, at Yad Vashem and in Bet Terezin in Israel. On August 10, 1944, Seckbach died in Theresienstadt. She was burnt in the crematorium, with no grave and no marker.

In the camp, where one of her brothers had also been sent, she sometimes painted on paper she found in garbage cans. Seckbach did not depict scenes of documentation, which is the most common genre of the artists in the camps, and this is why her works are surprising, since at first glance they do not seem to have any connection to her circumstances. Thus, among her works can be found paintings of flowers, imaginary landscape,s and surrealistic portraits.

1940–1944: Les années ténèbres. Déportation et résistance des Juifs en Belgique. Musée Juif de Belgique. Bruxelles: 1992.

Afoumado, Diane. “Les dessins des concentrationnaires Français: Témoin de la résistance spirituelle dans les camps Nazis.” Revue d’histoire de la Shoah, Le monde Juif, 162 (1998): 96–126.

Albert-Lazard, Lou. Gemälde, Aquarelle, Grafik. Berlin: 1983.

Amishai-Maisels, Ziva. Depiction and Interpretation: The Influence of the Holocaust on Visual Arts. Oxford: 1993.

[no author indicated] Artists Witness the Shoah: Camp Drawings from the Collection of Bet Lohamei ha-Getta’ot and Yad Vashem. Sheffield: 1995.

Blatter, Janet, and Sybil Milton. Art of the Holocaust. New York: 1981.

Braham, Randolph L., ed. Reflections of the Holocaust in Art and Literature. New York: 1990.

Costanza, Mary S. The Living Witness: Art in the Concentration Camps and Ghettos. New York: 1982.

Créer pour Survivre. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Reims. Paris: 1995.

Dutlinger, Anne D., ed. Art, Music and Education as Strategies for Survival: Theresienstadt 1941–1945. New York: 2000.

Fenster, Hirsch. Nos artistes martyrs (Yiddish). Paris: 1951.

Flagmeier, Renate. “Lou Albert-Lazard: Zeichungen vom Leben in Gurs.” In Gurs:

Deutsche Emigrantinnen in französischen Exil. Berlin: 1991;

Gilzmer, Mechtild. “Blanche-Neige à Rieucros ou l’art de créer derrière les fils de fer barbelés.” In Les camps du sud-ouest de la France 1939–1944: Expulsion, internement et déportation, edited by Monique-Lise Cohen and Eric Malo. Toulouse: 1994.

Idem. Camps des femmes: Rieucors et Brens. Chroniques d’internées, Rieucros et Brens 1939–1944. Paris: 2000.

Gittko, Lisa. Solidarity and Treason: Resistance and Exile 1939–1940. Evanston, Illinois: 1993.

Green, Gerald. The Artists of Terezin. New York: 1978.

Gurs: Deutsche Emigrantinnen in französischen Exil. Werkbund-Archiv, Martin-Gropius-Bau. Berlin: 1991.

L’internement des juifs sous Vichy. Centre de Documentation Juive Contemporaine, Paris: 1996.

Kagan, Raya. Hell’s Office Women (Oswiecim Chronicle) (Hebrew). Israel: 1947.

Lionel, Richard. L’Art et la Guerre: les artistes confrontés à la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Paris: 1995.

Lurie, Esther. A Living Witness: The Kovno Ghetto. Tel Aviv: 1958.

Idem. Sketches from a Women’s Labour Camp. Tel Aviv: 1962 (re-edition of Jewess in Slavery. Rome: 1945).

Lurie, Esther. Jerusalem: 12 Drawings and Paintings. Tel Aviv: n.d..

Milton, Sybil. “Concentration Camp Art and Artists.” Shoah: A Review of Holocaust Studies and Commemorations 2 (1978): 10–15.

Idem. “Art of the Holocaust: A Summary.” In Reflections of the Holocaust in Art and Literature, edited by Randolph L. Braham. New York: 1990.

Mittag, Gabriele. Es gibt nur Verdammte in Gurs: Literatur, Kultur und Alltag in einen südfranzösischen Intrernierungslager 1940–1941. Tübingen: 1996.

Idem, ed. Gurs: Deutsche Emigranten im Französischen Exil. Berlin: 1990.

Mittenzwei, Werner. “Das weithin unbekannnte Leben der Sylta Busse.” Sinn und Form 3 (1990): 631–641.

Novitch, Miriam. Spiritual Resistance: 120 Drawings from Concentration Camps and Ghettos 1940–1945, Milan: 1979.

Idem. Spiritual Resistance: Art from Concentration Camps 1940–1945: A selection of drawings and paintings from the collection of Kibbutz Bet Lohamei ha-Getta’ot, Israel. USA: 1981.

Reber, Gabriele. Amalie Seckbach. Unpublished research, Usingen: n.d.;

Rosenberg, Pnina. “Visual Art in French Internment Camps as Reflecting the Everyday Life of the Inmates.” (Hebrew) Ph.D. diss., University of Haifa, 1999.

Idem. Images and Reflections: Women in the Art of the Holocaust. Ghetto Fighters’ Museum: 2002.

Idem. “Mickey Mouse in Gurs: Graphic Novels in a French Internment Camp.” Rethinking History: The Journal of Theory and Practice 6 (2002): 273–292.

Idem. Salon des Refusés: Art in French Internment Camps. Ghetto Fighters’ Museum: 2000.

Idem. “Women Artists in Auschwitz.” The Last Expression: Art and Auschwitz. Illinois: 2003.

Idem. L’art des indésirables: l’art dans les camps d’internement français 1939–1944. Paris: 2003.

Salomon, Charlotte. Charlotte: A Diary in Pictures. New York: 1963.

Idem. Charlotte: Life or Theater: An autobiographical play by Charlotte Salomon. New York: 1981.

Schaul, Dora. “Un camp d’internement: Rieucros en Lozère.” In Cévennes, Terre de refuge 1940–1944, edited by Philippe Joutard, Jaques Poujol and Patrick Cabanal. Montpellier: 1988.

Idem. “Une antifasciste dans les services de la Wehrmacht.” In Exilés en France: souvenirs d’antifascistes allemands émigrés (1933–1945), edited by Gilbert Badia. Paris: 1982.

Schramm, Hanna. Vormeier, Barbara. Vivre à Gurs. Un camp de concentration français: Paris: 1979.

Stodolsky, Catherine. Malva Schaleck (1882–1944): Prague, Vienna, Terezin, Auschwitz. Unpublished research, Munich, n.d..

Szymańska, Irena. Suffering and Hope: Artistic Creations of the Oświecim Prisoner. n.d..

Toll, Nelly. Without Surrender: Art of the Holocaust. Philadelphia: 1978.

Tory, Avraham. Surviving the Holocaust: The Kovno Ghetto Diary. Edited with an introduction by Martin Gilbert; textual and historical notes by Dina Porat. Cambridge, MA: 1990.

Zeitoun, Sabine. Foucher, Dominique, eds. La masque de la barbarie: le ghetto de Theresienstadt 1941–1945. Lyon: 1998.