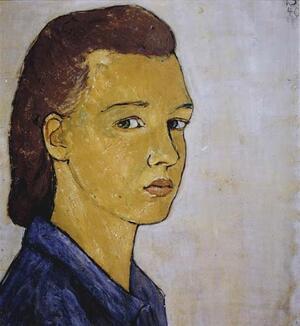

Charlotte Salomon

Charlotte Salomon was twenty-three years old in 1940 when she made a painting of her face—a nameless, stateless, Jewish face. A talented graphic artist, Salomon lived a life surrounded by death. Not only had her father been sent to a concentration camp after the Kristallnacht pogrom in 1938, but a total of eight members of her family committed suicice. Salomon memorialized their lives with her artwork, creating a slightly fictionalized depiction of her family members' lives. She packaged and hid her work, “Life? Or Theater?” before she was killed in Auschwitz. Her work was found after the war by relatives and donated to the Jewish Historical Museum there in Amsterdam. What remains of Salomon is the great graphic power and the excruciating struggle to know and record the truth.

“The war raged on and I sat by the sea and saw deep into the heart of humankind.”

— (Charlotte Salomon, 1942)

Personal Life and Family

Charlotte Salomon was twenty-three years old in 1940 when she made a painting of her face—a nameless, stateless, Jewish face. At the time, she was living as a refugee from Nazism in Villefranche on the French Riviera, and she had just made a startling discovery: that eight members of her family, one by one, over the years, had committed suicide. With this traumatic revelation in mind, she arrived at what she called “The question: whether to take her own life or to undertake something eccentric and mad.” Something “eccentric and mad” turned out to be an artwork in over seven hundred scenes, painted during one year (1941–1942), enriched by dialogues, soliloquies, and musical references, arranged into acts and scenes, and titled “Life? Or Theater? An Operetta.” This massive artwork recounted the story of her Berlin Jewish family from World War I up to the day in 1941 when she decided to paint her life rather than to take it, then sat down by the Mediterranean “and saw deep into the heart of humankind.”

The story she recounted (a true one but in fictionalized form) started with the 1913 suicide of Charlotte Grunwald, daughter of Ludwig and Marianne Grunwald, highly cultured residents of Berlin, and sister of Fränze Grunwald, whose shocked reaction drove her to save others by becoming a nurse. In the hospitals of World War I, she fell in love with a young surgeon named Albert Salomon. Their marriage resulted in the birth, on April 16, 1917, of a daughter Charlotte, named after the sister who had taken her life.

In the tense atmosphere of interwar Berlin, little Lotte Salomon watched her father overwork to become a professor at the Berlin University Medical School, and her mother turn to lonely despair. In 1926, when she was nine, Lotte was told her mother had died of influenza. In fact, she had thrown herself out of a window. This and other suicides in the maternal family were kept secret from Lotte for the next thirteen years, for the startling increase in suicides, most dramatically among educated, middle-class German Jewish women, was considered dangerous and shameful. The effect of loss and silence was to make Lotte Salomon both solitary and profoundly observant.

In 1930 Albert Salomon remarried, a dramatic opera singer named Paula Salomon-Lindberg, who brought into Lotte’s life many acquaintances from the musical world of Berlin, a strong Jewish practice that resulted in Lotte’s confirmation at a synagogue, and a profound relationship of love. In fact, the first paintings made by Lotte around the age of thirteen were prompted by the need to set down her stepmother’s face.

Nazi Rise to Power

After the Nazis came to power in 1933, Lotte’s father lost his job and began practicing at the Jewish Hospital in Berlin, Paula Salomon lost her opera career and began singing for the newly formed Jewish Cultural Association (the Kulturbund), while Lotte, at around age sixteen, dropped out of school and began drawing on her own. In 1936 she was admitted to the famous State Art Academy in Berlin which allowed only 1.5 percent of the school to be Jewish. There she received conventional but excellent training and probably observed modern art at the Nazis’ famous Degenerate Art Show in 1938. She also attended the Kulturbund’s many outstanding performances for Jewish audiences, where she learned to see art as a source of morale and a means of self-expression when little was allowed. During those years she also began a passionate love affair with a Jewish musician twice her age, Alfred Wolfson, who came into her household as an accompanist for Paula. He alone saw Lotte’s depth and skill and encouraged her to search for her soul in painting, like Orpheus entering the underworld.

With the pogrom of November 9 and 10, 1938 (“Kristallnacht”), everything changed for the Salomon family. Albert Salomon was tortured in the concentration camp of Sachsenhausen and after his release, Lotte was sent for safety to her maternal grandparents in southern France. Arriving in Villefranche in January 1939, she found her grandmother deeply depressed, tried to rescue her, but failed. In spring 1940, she witnessed her grandmother’s suicide, learned from her grandfather of seven other family suicides, including her own mother’s, and saw herself as designated heir to this terrible legacy. “Dear God,” Charlotte cries out in the paintings, “just let me not go mad.” To her parents, now refugees in Amsterdam, she wrote: “I will create a story so as not to lose my mind.”

Later War Years and Death

In May 1940 France’s Vichy government imprisoned German nationals as France’s enemies, sending Lotte and her grandfather to the concentration camp of Gurs in the Pyrenées, where she watched many artists produce works amid wretched conditions. Released in summer 1940, they returned to the Villefranche home of Ottilie Moore, a generous American to whom Charlotte Salomon dedicated the artwork she was about to begin. Supporting herself by painting greeting cards and portraits for Ottilie Moore, she eventually moved away from her grandfather in 1941 and began creating her autobiographical masterpiece in St. Jean Cap Ferrat, where an innkeeper remembered her humming tunes while painting. Her technique was to paint scenes from her life, attach tracing-paper overlays with words and melodies, create a playbill introducing the characters, add a narrator, summon an invented audience, and announce “This play is set in the period from 1913 to 1940 in Germany, later in Nice.” The notebook-size paintings were done in gouache, with bright exquisite colors in the early scenes, darkening as the story proceeded, while the dialogues and narrations ranged from witty and sardonic to grave and desperate. Using all the devices of drama, the artist created something unique in the history of art and of autobiography. Yet at the same time, the idea of creating profiles and remembrances occurred to persecuted Jewish artists and writers all over Europe.

Essential to Lotte Salomon’s own safety, the Riviera was occupied by Italy in 1942, and Italians were not deporting Jews. Returning to Villefranche, she moved in with another German-speaking Jewish refugee, Alexander Nagler, and after she became pregnant, they felt safe enough to register their marriage, on June 17, 1943, at the Nice town hall. Although local antisemitism ran high, the Italian zone of France remained a kind of sanctuary. This anomaly so infuriated the Germans that when they occupied the Riviera in September 1943, Adolf Eichmann sent his best agent, SS Captain Alois Brunner, to carry out roundup operations there. Meanwhile, a large-scale rescue plan by an Italian Jewish banker and a Capuchin monk persuaded many Jews, probably Lotte and Alexander Nagler among them, to remain near Nice. Brunner, however, moved quickly, and on September 24, 1943, arrested both of them in Villefranche, shipping them by train to the transit camp of Drancy outside Paris. In this camp, also run by Brunner, inmates had no idea where the deportation trains were going. Asked her occupation for a transport list, Charlotte Salomon said truthfully “graphic artist.” On October 7, 1943, Transport No. 60 left France and arrived three days later at an unknown destination. As with most transports from France and other places, the first selection beside the train was the crucial one, separating men from women and children. At this last station on the long road toward extinction, men like Alexander Nagler were sometimes sent into slavery. Women usually, pregnant women always, were killed on arrival. And so, in her very first hour at Auschwitz, Charlotte Salomon lost her life.

Legacy

But she had packaged and hidden her work, “Life? Or Theater?”—saying to a trusted friend, “Keep this safe. It is my whole life.” Her “whole life” was found in Villefranche after the war by Albert and Paula Salomon. Brought to Amsterdam, it was donated to the Jewish Historical Museum there. Albert and Paula Salomon had survived the war by hiding in Holland; later, Albert resumed his career as a physician and Paula became a distinguished teacher of voice, though never again a singer; Lotte’s lover Alfred Wolfson had fled to England where he trained singers in an unusually liberating method; Alexander Nagler died of exhaustion in Auschwitz; SS Captain Alois Brunner escaped to Syria where he designed antisemitic propaganda and torture machines for the government; though tried in absentia in several countries, he was never apprehended. “Life? Or Theater?” went on permanent exhibit at the Jewish Historical Museum of Amsterdam, while the collection also traveled in major exhibits throughout the world.

What remains of Charlotte Salomon herself is the great graphic power and the excruciating struggle to know and record the truth. In the thick of despair she wrote: “If I can’t find any joy in my life or my work, I am going to kill myself.” But at the end of “Life? Or Theater?” she realized that “she did not have to kill herself like her ancestors, for she could create her world anew, out of the depths.” On one of the late paintings appears a prophetic caption: “I will live for them all.”

Works by Charlotte Salomon

The paintings of Life? Or Theater? and all studies for the work are owned by the Charlotte Salomon Foundation of Amsterdam and housed in the Jewish Historical Museum of Amsterdam. Paintings can be viewed on the museum’s web site: www.jhm.nl

Salomon, Charlotte. Charlotte: Life or Theater? An Autobiographical Play by Charlotte Salomon. Translated by Leila Vennewitz. New York: 1981. The first full edition of the work published in English.

Salomon, Charlotte. Charlotte Salomon: Life? Or Theatre?. London: 1998.

A smaller-format full edition, including essays, prepared for an exhibition at the Royal Academy, London.

Salomon, Charlotte. Charlotte: A Diary in Pictures. New York: 1963. A first short edition of eighty reproductions.

Films

Herzberg, Judith, and Franz Weisz. Charlotte. 1980. First feature film with actors, in English.

Dindo, Richard, and Esther Hoffenberg. C’est toute ma vie. 1992. Feature and documentary film, in French and English.

Fischer-Defoy, Christine, Daniela Schmidt, and Caroline Goldie. Paula Paulinka. 1995. Documentary film about Paula Salomon.

Felstiner, Mary. To

Paint Her Life: Charlotte Salomon in the Nazi Era. New York: 1994;

Berkeley: 1997.

Full-length biography with extensive illustrations and bibliography.

Fischer-Defoy, Christine. Charlotte

Salomon—Leben oder Theater? Berlin: 1986.

Anthology of essays and interviews in German.

Kaplan, Marion K. Between

Dignity and Despair: Jewish Life in Nazi Germany. New York: 1998.

Overview of the condition of German Jews under the Nazis.

Ofer, Dalia, and Lenore Weitzman, editors. Women

in the Holocaust. New Haven: 1998.

Anthology of essays.

Films

Herzberg, Judith, and Franz Weisz. Charlotte.

1980.

First feature film with actors, in English.

Dindo, Richard, and Esther Hoffenberg. C’est

toute ma vie. 1992.

Feature and documentary film, in French and English.

Fischer-Defoy, Christine, Daniela Schmidt, and Caroline Goldie. Paula

Paulinka. 1995.

Documentary film about Paula Salomon.