Mary Frank

Mary Frank’s love of dance informed her artwork, as she focused on the human body in motion. Frank studied dance with Martha Graham from until she married the photographer Robert Frank and switched from dance to art. Her drawings and sculptures were influenced by dance and photography. Frank sculpted in various media, but she began working in clay in 1969, creating disjointed human forms. Frank's daughter was killed in a plane crash and her son was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s disease, and her grief was reflected in her art. In the 1980s she began painting, creating works of vivid color. She has taught as an artist in residence at many institutions, and her work is displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Smithsonian, among many other prominent institutions.

According to the great American mythologist and historian Joseph Campbell (1904–1987), artists are a culture’s mythmakers and “Myths are so intimately bound to the culture, time and place, that unless the symbols, the metaphors, are kept alive by constant recreation through the arts, the life just slips away from them.” Mary Frank’s figure sculptures have been described as sensual, sublime, erotic, metaphorical, poetic and profoundly moving. Frank herself has said, “All myths deal with transformations.” It is this view which marks Mary Frank as unique among contemporary artists. At a time when figurative work has not been an artistic imperative, Frank imparts a sense of the timeless and elemental to her work, placing her among the foremost figurative artists of our time.

Early Life and Family

Mary Frank comes from a humanistic school of sculptural expression and art. Born in London on February 4, 1933, Frank has stated, “I was brought up to be an artist.” She is the only child of American-born painter Eleanore Lockspeiser (1900–1986) and Edward Lockspeiser (1905–1973), a prominent English musicologist and art critic. Eleanore is quoted as saying that “art was the only important thing in our household.” Mary Frank remembers her mother as an abstract artist who painted “as if her life depended on it.”

When Britain declared war on Germany in 1939, Mary was evacuated from London and moved to many church boarding schools in the countryside. This experience of displacement made her vividly aware of being an outsider because her family was both atheist and Jewish. Prior to June 1940, when their home in London was bombed and all her paintings destroyed, Eleanore took her daughter to live with her maternal grandparents, Gregory and Eugenie Weinstein, in Brooklyn, New York. (In the 1870s Gregory Weinstein, a fierce atheist who was born the son of a Russian rabbi in Vilna, Lithuania, had emigrated to the United States, where he founded a multilingual International Press in downtown Manhattan.) Edward remained in London in the fire service. The Lockspeiser marriage did not survive the separation of war and ended in divorce before the Allied victory. Mary saw her father only four more times in her life.

Dance and Art

Once she began living in New York, dance became more important for Mary than painting. She studied modern dance with the legendary Martha Graham from 1945 to 1950. In 1947 Frank was admitted to the High School for Music and Art in Manhattan. However, since it had no dance program, by 1949 she chose to continue at the Professional Children’s School, where she majored in dance and graduated in 1950. The influence of Martha Graham and dance deeply influenced her art for the rest of her life. She was and still is obsessed with capturing the figure in motion. “At the age of seventeen,” she recalls, “I gave up dancing and concentrated on art.” In 1950 she began studying wood carving in the studio of Alfred van Loen and drawing with Max Beckmann at the American Art School in New York. “I studied painting so little … I’d have loved to study with El Greco or Bonnard or a calligrapher.” Frank never had any formal training in sculpture, although she did study life drawing briefly with Hans Hofmann in 1951 and 1954 in evening classes at Hofmann’s Eighth Street school. However, at that point in her life Mary Frank was married and had two small children.

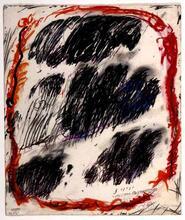

While Frank was a junior at the Professional Children’s School, she met Robert Frank, the great Swiss photographer, nine years her senior (born Zurich November 9, 1924), whom she married in 1950. Their son Pablo (after Picasso) was born on February 7, 1951, and a daughter, Andrea, was born on April 21, 1954. In 1955, after winning the prestigious Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship Award, Frank took his family cross-country in a car for two years, from Texas to New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada and California, to document the distinctly unique culture of America during the 1950s. His brilliant photographic collection titled The Americans was published in 1958. Frank’s dark, shadowy photographs of people taken with a fast Leica in a cinematic style influenced Mary Frank’s drawings, which share qualities of stark black and white contrast, silhouetting and filmic instantaneousness, as if she had just taken a snapshot.

Art Career and Exhibitions

When Mary Frank first began exhibiting in 1958, she had been exploring mythological themes, primitive art, and archetypal human and animal gestures, in a large variety of sculptural mediums, such as wax, wood, plaster, and bronze, as well as powerfully expressive drawings in charcoal, ink wash and Conté crayon. Much of her inspiration was drawn from viewing Egyptian and Etruscan sculpture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the sculpture of Henry Moore, Giacometti and Brancusi, and the drawings of Edgar Degas. The American Museum of Natural History, botanical gardens and parks, beaches and the Bronx and Central Park zoos were also great favorites for drawing fast-moving birds and animals such as gulls and cranes, horses, lions, and gazelles.

In 1968 Frank began her twenty-two-year relationship with Zabriskie Gallery in New York. In 1969, inspired by her admiration for the sculpture and pottery of Margaret Israel, Frank turned to working in clay, the one medium which allowed her the flexibility she needed to create her earthy, erotic body of figurative sculptures distinguished by their emotional intensity, sensual beauty and evocative poetic metaphors. In 1973 Mary Frank purchased a summer home in Lake Hill, New York, and built her first kiln. By this time she had separated from her husband, whom she divorced in 1969. On December 28, 1974, Mary’s twenty-year-old daughter, Andrea, was killed in a plane crash in the Guatemalan jungle near the Mayan ruins at Tikal. One year later, in 1975, Mary’s mother nearly died from cancer, and within a year of his sister’s death, Pablo developed Hodgkin’s disease. After Andrea died, Frank’s grief was expressed in a number of works, such as Head with Ferns, ceramic, 1975, and Head with Petals, ceramic, 1976, a small work which tenderly shows a young woman’s face with eyes closed, enveloped by petals of clay gently stenciled with ferns. Frank has said of the faces of her women that they exist in a state of grace conveyed by the Yiddish saying, “Out of longing, and out of song, time was created. And there is always just enough time for one more day.” She continues, “I want to make that state of grace palpable.”

Honors and Awards

Mary Frank’s career has spanned over five decades. Widely acclaimed since the late 1970s as a figurative sculptor in clay, she is also a superb draftsman. Largely self-taught, her personal vocabulary of metamorphosis, mythological and evolutionary themes is often expressed at its poetic best in her prolific output of drawings and monoprints in the fine arts, as well as in the graphic and illustrative arts, particularly in her illustrations for books.

Since the mid–1980s Frank has increasingly turned to painting as her primary medium, inspired by a greater need to work in color, even to the point of painting two of her ceramic sculptures of this period, Ethiopian and Woman in Wave, Spring, both 1986–1987, in vivid shades of a blue patina.

In 1986 Mary Frank’s mother Eleanore passed away. On November 11, 1994, her son Pablo died in Pennsylvania. Today Mary Frank lives and works in Lake Hill, New York, and New York City, with her husband, Leo Treitler, a pianist and scholar of music, whom she married in June 1995.

Mary Frank was elected to the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters in 1984. She is the recipient of numerous awards and honors, including two Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship Awards in 1973 and 1983, the Lee Krasner Award of the Pollock-Krasner Foundation in 1993, and the Joan Mitchell Grant Award in 1995.

She has had two retrospective exhibitions at the Neuberger Museum of Art, State University of New York at Purchase: Mary Frank: Sculpture/Drawings/Prints in 1978 and Mary Frank: Encounters, 2000. A third retrospective, Natural Histories: Mary Frank’s Sculpture, Prints, and Drawings, was held at the DeCordova Museum, Lincoln, Massachusetts, 1988.

Frank’s work is included in the permanent collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The National Museum of American Art at the Smithsonian Institution, The Library of Congress, The Art Institute of Chicago, The Museum of Modern Art at Yale University, and The Jewish Museum. Recent teaching honors include the Milton Avery Chair, Distinguished Professor at Bard College in New York, 1992; New York Academy of Art, 1993; Graduate Faculty, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, 1992–1993; Artist-in-Residence, Pasadena City College, March 1995.

Books

Herrera, Hayden. Mary Frank. New York: 1990. The best source for viewing the full range of Mary Frank’s sculptures, paintings, drawings and prints.

Exhibition Catalogs

Frank, Mary, Linda Nochlin and Judy Collischan. Mary Frank: Encounters. New York: 2000. Exhibition catalog which reproduces more than forty of Mary Frank’s paintings.

Frank, Mary, Hayden Herrera, and Stella Kramrisch. Natural Histories: Mary Frank’s Sculpture, Prints, and Drawings. Lincoln, MA: 1988.

Danly, Susan, and Martha A. Sandweiss. Language as Object: Emily Dickinson and Contemporary Art. Amherst, Mass.: Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, in association with the University of Massachusetts Press, 1997. Unique anthology showcasing the work of visual artists and poets in response to the nature poetry of Emily Dickinson (1830–1886). Mary Frank chose to illustrate Dickinson’s poems using papyrotamia, or “shadow papers,” images which have been cut from flat sheets of paper using scissors, visible only when light shines through the slits. Frank’s luminous works resonate perfectly for a book about Dickinson, who lived in nineteenth-century Victorian America, when this art form was at the height of its popularity. Frank says, “It’s a kind of dance with the paper. I try to find forms and create space without cutting anything out of the paper.”

Essays, Articles And Reviews

Kingsley, April. “Mary Frank: A Sense of Timelessness.” Artnews 72/6 (Summer 1973): 65–67. Beautiful, insightful article. Essential reading on Mary Frank.

Kramer, Hilton. “The Sculpture of Mary Frank: Poetical, Metaphorical, Interior…” The New York Times, February 22, 1970. Critic Kramer points out that the work of Mary Frank not only exists outside contemporary time and art, but that even her techniques are ancient.

Kramer, Hilton. “Art: Sensual, Serene Sculpture; the Heroism of the Erotic is Theme of Mary Frank.” The New York Times, January 25, 1975; Mellow, James R. “Mary Frank Explores Women’s Erotic Fantasies.” The New York Times, January 19, 1975; Kramer, Hilton. “Lyric Freedom Marks Mary Frank’s Drawings.” The New York Times, April 17, 1971; Harrison, Helen A. “A Sensual and Enigmatic World.” The New York Times, December 23, 1979; Lombardi, D. Dominick. “An Encounter with the Metaphorical.” The New York Times, November 26, 2000; D’ Souza, Aruna. “Mary Frank and the Search for Self.” Art in America, March 2001.

Illustrated Books

Coatsworth, Elizabeth Jane, and Mary Frank. The Enchanted, an Incredible Tale. New York: 1968; Cohen, Joan Lebold, and Mary Frank. Buddha. New York: 1969; Gibbs, Alonzo, and Mary Frank. Son of a mile-long mother. New York: 1970.

Matthiessen, Peter, and Mary Frank. Shadows of Africa. New York: 1992. Mary Frank collaborates with nature writer Peter Matthiessen in seventy paintings and drawings illustrating his essays on African animals. Frank displays a muscular rhythm and energy for capturing figures and animals in motion, a skill more allied with dancing than painting and consistent with her early training as a dancer with Martha Graham.

Dickinson, Emily, Jonathan Cott, and Mary Frank. Skies in Blossom: The Nature Poetry of Emily Dickinson. New York: 1995; Williams, Terry Tempest and Mary Frank. Desert Quartet, An Erotic Landscape. New York: 1995. Beautifully illuminated book with drawings and paintings by Mary Frank.

Children’s Literature

Sills, Leslie. Visions: Stories About Women Artists. Morton Grove, Illinois: 1993. Color illustrations accompany the biographies of artists Mary Cassatt, Betye Saar, Leonora Carrington and Mary Frank. Written in a clear, direct style for children aged nine years and older, the book presents details about Mary Frank’s life not generally known, based on a conversation the author had with the artist in New York City in 1991. Informative reading highly recommended for all ages.