"Second Generation" Women Artists in Israel

Second generation descendants of Holocaust survivors were born to families engulfed in feelings of death and bereavement. Many of them internalized the grim atmosphere of absence, emptiness, and loss they inherited. The artists among them, men and women alike, expressed this atmosphere in their art in different intensity and power. Nevertheless, several themes have preoccupied only the women artists of the second generation as expressed in their work: their mothers' horrific and traumatic experience during the Holocaust; being a compensation and replacement for family members who had died; and serving as a memorial candle for those family members who perished. These subjects illustrate the role of the Holocaust in their inner world, and the impact of their parents’ experience during the Holocaust.

Introduction

A number of studies from the mid-1980s onward have demonstrated the impact of the Holocaust on visual art, in particular for artists who themselves experienced the agony of the Holocaust, but also among their contemporaries. These artists portrayed the Holocaust’s atrocities and responded to the horrific trauma through various forms of expression. Now, more than seventy years after the Holocaust, it is apparent that its impact has carried over into the works of so-called “second generation” artists as well.

The term “second generation” in this context refers to children born after World War II to parents who lived in Europe under the Nazi regime and suffered its horrors, whether in the ghettos, the camps, in hiding, fleeing from place to place, or as fighters and partisans. It is a socially heterogeneous group whose members come from different religious, economic, political, and educational backgrounds. The circumstances of their parents’ survival varied from case to case; likewise, some survivors spoke of their brutal experiences, while others suppressed their traumatic past beneath a blanket of silence. In both cases, however, the Holocaust has been a presence in the lives of the second generation and an inescapable influence, as Nava Semel writes in her book Kova Zekhukhit (Hat of Glass): “A lack of knowledge does not mean that the knowledge, however elusive, does not lie dormant within the dermis, in corpuscles which persist in their refusal to come together. I had wanted my childhood to drift into someone else’s. Wherein does a lack of knowledge lie? Inside me a tide forms, washing every bay, after an era of icebergs” (Semel, 82). The common link among the second generation is the family legacy in which the brutalities of the Holocaust, the loss, the death, the destruction have left a wide, emotion-laden gap. Their life stories make them a unique group with shared generational experiences.

Numerous studies reveal the intensity of the impact of the survivors’ trauma on their children, and the resultant centrality of the Holocaust in their inner lives. The members of the second generation were born to families engulfed in feelings of death and bereavement. Many of them internalized the grim atmosphere of absence, emptiness, and loss in which they were raised; ultimately, it became a central motif of their identity and one that they were forced to confront. Members of the second generation frequently grew up in homes where murdered family members continued to exist—whether through endlessly repeated stories or the few pictures that survived, or alternatively, amid the silence and mystery that surrounded the figures of the dead. Hand in hand with their life in the present, members of the second generation found themselves caught in the traumatic past of their parents, of which death was a central component. This created a situation in which a significant part of the emotional world of the second generation was dominated by death and its consequences, forcing them to confront the emotional burden they had inherited. As a result of the bleak atmosphere of loss and death absorbed from birth by the second generation, the Holocaust took over their imaginations and their inner world, filling them with subjects, symbols, and images they felt a tremendous need to address. The artists of the second generation, men and women alike, have explored many common themes, making use of similar symbols and images. Nevertheless, several themes have preoccupied only the women artists of the second generation as expressed in their work.

Works created from the mid–1960s to the early 2000s indicate how Israeli women artists born to survivors have dealt with the legacy of the Holocaust. Their art reflects their mothers’ Holocaust trauma. They demonstrate how second-generation women artists have coped with being “replacements” for family members who perished in the Holocaust—in their parents’ eyes, a posthumous expression of victory over the Germans. Other works reflect how daughters of survivors have dealt with their role as “memorial candles,” taking upon themselves the task of serving as a link in the historical chain of the Jewish people for the sake of the past that was obliterated.

Daughters and Mothers

A number of psychological studies have found that, of all the identities a mother passes on to her daughter, the most significant are those that she experienced proximate to her own motherhood. It is therefore reasonable to assume that women survivors who became mothers soon after the Holocaust passed on to their daughters the trauma and horror they had experienced during the Holocaust. Studies point to a symbiotic connection, in particular between survivor mothers and their children, through which feelings of trauma are transmitted to the second generation. Other researchers claim that there are dreams and fantasies common to survivor parents and their children, and that in fact the children are reliving the experiences of their parents.

Already as a young girl, Rivka Miriam struggled with the profound sense of trauma transmitted to her by her parents, in particular her mother. She was born in Israel in 1952 to Leib and Esther Rochman, both from Minsk Mazowiecki, Poland, where they were imprisoned in the ghetto and later married, in 1942. The couple managed to escape the ghetto and found shelter in the home of a locale Pole. Together with them in their hiding place were Esther’s sister and two friends of Leib’s, one of whom later became his brother-in-law. All five of them at various points took on assumed identities, fled, and hid in a cellar and in pits in the forest.

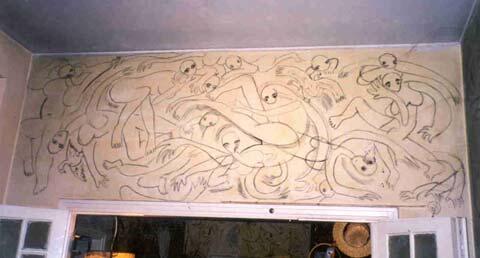

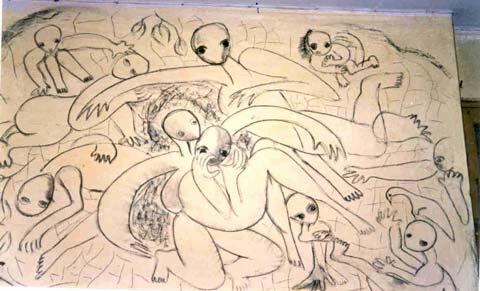

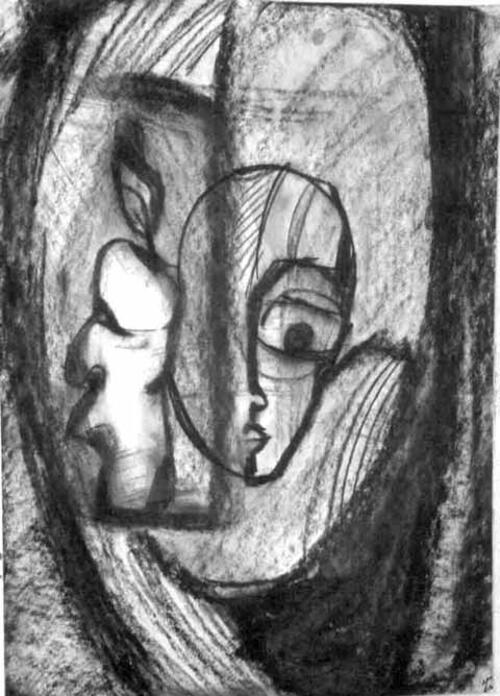

Rivka Miriam was named after her father’s mother, Rivka, and his sister, Miriam, who perished on the same day in Treblinka. In many of her works, she includes family members who are gone, precisely because her parents spoke so freely of their lives, their personalities and the way in which they died. As she related in an interview in 1988: “In our family, the relatives who had been killed were spoken of openly and freely, with much lightness and humor mixed with great pain. But these were not larger-than-life figures. I felt them as beings who were constantly around me, as my partners in conversation” (interview, 1998). As a young girl of twelve, Rivka Miriam felt an intense need to release the spirits of her dead relatives that were trapped in her imagination and her inner world. She chose to draw them on the walls of her parents’ home, thereby giving them concrete form and enabling her to carry on a dialogue with them. Rivka Miriam’s parents did not object to her drawing on the walls of the house; on the contrary, they welcomed the opportunity it afforded her to unload this heavy burden. The figures in the wall drawings exist to this day alongside the everyday life of the family. The first wall drawings were done in 1964 in charcoal. They are airy sketches of figures drawn in outline form, lying atop one another or hovering, their limbs splayed in every direction. They are drawn without hair, with bulging eyes, and usually without a mouth. The figures gaze at us, speechless and unresponsive, reminiscent of the figures of muselmänner (dull-eyed concentration camp inmates who had lost the will to live).

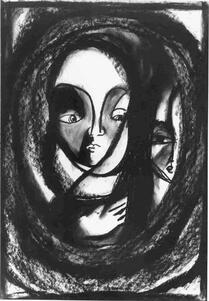

Somewhat later, in 1965, drawings rendered in pastels were added in the empty spaces; they portrayed emaciated figures, some of them bald, who appeared to be hiding and were looking out with frightened eyes, all enclosed within an oval. In the first drawing, for example, we see the figure of a woman without hair, her mouth closed and eyes wide open, looking sideways in terror at something unseen. Her femininity is underscored by a large green bosom. The background is drawn in splashes of green and black surrounding the figure.

In the second picture, also within an oval, the figures of two young girls are crowded together with the head of a young boy peeking at them. Both scenes powerfully convey a sense of anguish, horror, and fear, recalling the situations where victims were packed in close quarters in hiding places. Although these drawings do not portray specific people, they are influenced by the parents’ stories, their hiding places, and the moments of terror that they experienced.

In two works labeled Untitled from 1965–1966, the artist addresses the stories of her parents’ experiences by means of her close relationship with her mother. The first drawing portrays two sad, frightened young women; the face of one is shown in full, with her hand resting on her chest, while the second figure is shown only in part. Both are surrounded by a series of ovals, suggesting a sense of being closed in, looking up from the depths, being trapped, or peering out of an opening. The portrait is influenced by the odyssey of terror of the artist’s mother and aunt, whose own experiences may have inspired it. One might even go so far as to suggest that the figures in the drawing are Rivka Miriam’s grandmother and her father’s sister (after whom she is named)—personalities that she is subconsciously “invoking” from her inner world and identifying with.

In the second work, the artist portrays two figures, one a woman, the other a young girl, with a look of terror and anguish in their eyes. Hovering next to them are tall, thin shadowy figures, two in black and one in gray. One of these figures is reaching out its arms toward the young girl as if to embrace her. The young girl, who resembles Rivka Miriam, is staring straight ahead with a sad look, while the figure of the woman, apparently her mother, is gazing at the shadowy figures, her eyes wide with horror. Rivka Miriam and her mother had a strong bond; hence the drawing suggests that both mother and daughter are haunted by the ghosts of the dead, portrayed here as shadows. Although these works were executed in black and white, the many shades of gray add a strong sense of dimensionality, expressiveness, and power.

The theme of “revisiting” the Holocaust is a prominent motif among the second generation of Holocaust survivors, stemming largely from the subconscious message transmitted by survivors to their children, as if to say: Experience the Holocaust and keep it alive for our sake. The relationship between the survivors and their children is a symbiotic one that finds expression in the obsessive need to return, time after time, to the Holocaust and emerge from it alive once again. The resulting behavioral schema can be likened to an imaginary time tunnel in which the second generation are able to transfer some of their parents’ past into the present and make it part of their “self” for a certain time frame in order to try to understand what their parents, or the family members who perished, experienced.

For some members of the second generation, images from the Holocaust appear in their dreams, their daytime reveries, and the edges of their consciousness, causing them to identify with the victims. They imagine, for example, being brutally seized by the Nazis, or see themselves in a concentration camp or crowded into a hiding place. The preoccupation of the children of survivors with the horrendous event that preceded their birth is expressed in a tendency to reenact that suffering in their own lives. They imagine that it is happening to them and, in this way, attempt to clarify for themselves what they would have done had they been there (a recurring theme among interviewees in Helen Epstein’s book, Children of the Holocaust). Such a situation occurs because many details from their parents’ past are like a mystery that they must unravel. Since they cannot explore the subject directly with their parents, they do so through their imagination and their art. For daughters of survivors, there are additional questions regarding the exploitation of their mothers’ femininity, and that of women in general, during the Holocaust.

Yocheved Weinfeld, for example, grapples with the question of how she would have behaved had she been “there.” Weinfeld was born in Poland in 1947, the only daughter of Holocaust survivors. Her father Natan Ernst, whose parents were killed by the Germans, spent the war years in hiding. Her mother, Klara Goldstein, was in high school when the war broke out. She managed to secure forged papers, enabling her to pose as an Aryan and work as a housekeeper in the home of an SS officer stationed in Poland. Her parents, who had met briefly when they were younger, were reintroduced by her maternal grandmother after the war. The couple married, and in 1957 the family immigrated to Israel. In 1967, the artist married David Weinfeld, an Orthodox Jew. The year 1975 proved traumatic for her: her mother died of cancer, and she and her husband divorced.

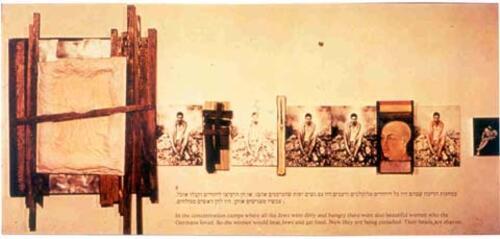

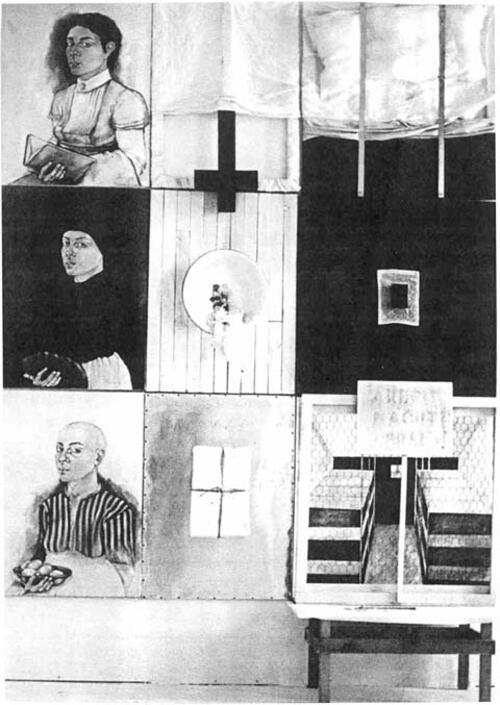

The silence and the mystery surrounding her parents’ experiences during the Holocaust, in particular her mother’s, led Weinfeld, as an adult, to ask questions about how they had survived and to engage in her own imaginings. From the 1970s onward, she frequently expresses her identification with victims of the Holocaust, in particular women, as reflected in the fact that she portrays herself with a shaved head and a striped garment like those worn by camp inmates. In her solo exhibition at the Israel Museum in 1979, one can see her early references to the Holocaust and the beginnings of her conscious identification with its victims. The exhibit consisted of ten works based on childhood memories of Poland, which she recaptures and presents in the form of a verbal description coupled with visual images. Each of the works is numbered in sequence and begins with a photograph of the artist from the period referred to in her recollection. The works contain images related to a particular event from the artist’s childhood in Poland and up until her Lit. "ascent." A "calling up" to the Torah during its reading in the synagogue.aliyah to Israel. Weinfeld does not neglect any medium, employing photography, drawing, collage, and sculpture to shift between the past and present. In the fabric of her memories, she revisits the events of the Holocaust and creates new situations in an attempt to understand what the victims experienced and what she would have done in their place. In her work entitled Number 8, Weinfeld wrestles openly with the question: As a concentrate camp inmate, would she have been a victim, a muselman, or a kapo (prisoner in charge of a group of fellow camp inmates, often viewed as a turncoat)? In her words: “In the concentration camps where all the Jews were dirty and hungry, there were also beautiful women whom the Germans loved. So, the women would beat Jews and get food. Now they are being punished. Their heads are shaved.”

Through her verbal descriptions, Weinfeld attempts to imagine how she would have behaved in the concentration camps. In so doing, she expresses her identification with the women who found themselves in this situation. She portrays herself in three sets of circumstances: As a young girl in Poland, in the small photograph on the right, she is unaware of her parents’ past and the fact that she is absorbing memories, words, voices, sights, and smells that will later become a repository of childhood associations. In the center of the work is a photograph of her as an adolescent, repeated five times, in which she is seen dressed in a transparent white nightgown, barefoot and with shorn hair. She is sitting on a pile of garbage, poking through it as if searching for food and, at the same time, looking up in search of salvation. The garbage pile is her way of identifying with the camp inmates whose heads were shaven and who lived amid filth and starvation. Weinfeld imagines herself seeking a solution to her situation: she wears a transparent white nightgown in hopes of attracting the attentions of a German officer who will make her a kapo. She is portrayed next as a kapo, after achieving her goal. She appears well groomed, with earrings and a lace collar, but remains a prisoner with a shaven head. In between the photographs, Weinfeld added objects related to the camp experience: a syringe with blue ink used to tattoo a number on the forearm of prisoners in Auschwitz, a composition of crosses intertwined with barbed wire against a backdrop of striped fabric. The crosses may allude to the fact that there were also Christian prisoners at Auschwitz, and the striped cloth is reminiscent of the prisoners’ uniforms; it draws a connection between the Jewish and Christian prisoners, who shared a common fate. The motif of the cross evokes an immediate association with the crucifixion of Jesus as a symbol of sacrifice. (Weinfeld is not the only artist to use the image of the cross in the context of the Holocaust; it has become an accepted artistic tradition to use the crucifixion as a symbol of Jewish suffering in the Holocaust. For a broader discussion of this topic, see: Amishai-Maisels, 180–197.)

On the leftmost side of the work, Weinfeld places an image of a bed with obvious signs of recent sexual activity. But she surrounds it with a wooden bar to indicate that these were not relations between two free people but between jailer and inmate; upon their completion, the female prisoner would return to her previous situation or continue on her way to the gas chambers.

In 1979, following this exhibition, Weinfeld traveled to the United States on a fellowship from the American-Israel Cultural Foundation and settled in New York. The following year, she married New York artist Steve Kasher, and in 1985 they had their only daughter, Talia. These events in her life led to the creation of several works that address her identification with victims of the Holocaust coupled with the theme of woman as victim. For example, her work You Look So Typically Jewish (1979–1980), which Weinfeld created immediately upon arriving in the United States, is “read” from left to right and has an English name to emphasize her new place of residence. The work is composed of three columns, each of which is divided into three horizontal panels. In the left-hand column, Weinfeld drew her self-portrait three times in the same pose; in each portrait, however, she is pictured in different clothing and holding a different symbolic object. To the right of these self-portraits, Weinfeld placed images in the two remaining columns, forming three horizontal rows with a self-portrait in each and two images alongside it.

In the first self-portrait, Weinfeld is shown as a pre-World War II European woman in a dress copied from a photograph of her grandmother, holding an open book. She appears educated and cultured and is dressed modestly, but there is no special symbol that suggests she is Jewish. One can assume that she represents secular, enlightened Judaism, which assimilated into European society before the war. In the panel to the right of the portrait, the artist places an inverted black cross covered partly with a white cloth, suggesting that there is no visible difference between the Jews that Weinfeld represented in her self-portrait and their Christian neighbors. And in the rightmost panel in this row, she presents an image reminiscent of an unmade bed, which we saw earlier in her work entitled Number 8, apparently an allusion to sexual permissiveness.

In the second portrait, Weinfeld is shown as a modestly garbed Orthodox Jewish woman in a black dress and head covering, holding a loaf of bread. One can assume from this representation that it was one of the central roles of the Jewish woman to provide her household with food. Art historian Gannit Ankori explains that bread, in this instance, symbolizes observance of the A biblical or rabbinic commandment; also, a good deed.mitzvah to set aside a portion of the dough when baking hallah, one of the commandments that the Jewish woman is obligated to perform. In the panel to the right of the portrait is a bowl containing a blood-soaked rag, an image associated with the state of Menstruation; the menstruant woman; ritual status of the menstruant woman.niddah (menstrual impurity). (Weinfeld had already related to this topic earlier in an exhibit at the Debel Gallery in Jerusalem in 1976, where she presented her own interpretation of the niddah purification process as laid out in the Lit. "the prepared table." A code of Jewish Law compiled by Joseph Caro (1488Shulhan Arukh law code.) The rightmost panel in this row is colored black as an echo of the black clothing in the self-portrait. In the center of the panel is a bright square, and on it, a black cube. This image evokes a sense of being isolated, closed off, oppressed, and relates to the portrait depicting an Orthodox Jewish woman in a segregationist society.

In the third portrait, we see Weinfeld with the striped uniform and shaved head of a concentration camp inmate; she is holding a bowl of potatoes. This is a direct identification with the fate of those in the camps, in particular the women. In the panel to the right of the portrait, the artist has tied a rectangular piece of white gauze, an allusion to feminine hygiene. In an interview with Ankori, Weinfeld explains: “I always thought about the trivial, seemingly unimportant things. I mean, besides the terrible things that went on in the camps, what did women do when they had their period?” (Ankori 1989, 25).

In the rightmost panel, Weinfeld created the image of an abyss bordered on both sides by wooden “bunks” stacked one atop the other, with the whole enclosed in an actual fence. This is meant to recall the concentration camps and death camps and the barracks into which the Jewish inmates, male and female, were packed, sleeping crowded together on tiered wooden planks in inhuman conditions. On the fence she hung a sign reading “Arbeit Macht Frei” (Work Shall Set You Free), a reminder of the false, cruel, and misleading statement that greeted the Jews on their arrival at Auschwitz. In front of the panel, she positioned a small wooden table on which lay a syringe stained with blue ink, evoking the numbers tattooed on the forearms of Auschwitz prisoners as part of their dehumanization. By portraying herself as a concentration camp prisoner and tying her self-portrait to the set of images alongside it, Weinfeld is expressing her direct identification with the fate of victims of the Holocaust in general and the women in particular.

In order to link the three rows that make up the work, Weinfeld allows the images of the black cross and the Arbeit Macht Frei sign to intrude slightly on the adjacent rows, thereby creating a sense of connection between the fate of the different women in the portraits. The name of the work (You Look So Typically Jewish) and the inclusion of Weinfeld’s self-portraits, each time as a Jewish woman with a different background, raise the complex question that clearly troubles the artist: Who is a “typical Jew”? Her answer to that question lies in the images above: Both the Jews who tried to integrate into non-Jewish society (as in the first portrait), and those who segregated themselves and maintained their Jewishness (as in the second)—regardless of their economic, social, or intellectual class, as expressed in the various symbols held by the subjects—were all sent by the Nazis to the same place, the death camps (as illustrated in the third portrait) solely because they were Jewish. This leads us to conclude that, in Weinfeld’s eyes, being a “typical Jew” means being a victim.

In a series of works, Racheli Yosef also deals with the scraps of information available to her about her mother’s experiences. She is the daughter of Holocaust survivors from Czechoslovakia. Her father was a prisoner at Auschwitz and worked at one of the factories that built camouflage aircraft for the Germans. In 1945, while on a “death march” near the end of the war, he managed to escape and was captured by the Russians. Her mother was also at Auschwitz, after which she was transferred to forced labor at a Siemens factory and later to Bergen Belsen; there, she was sent on a “death march” and ultimately liberated by the Americans. Her parents met in Budapest and immigrated to pre-State Palestine as part of the “illegal” Aliyah. As she puts it: “Somewhere in between the ‘sabra’ candor personified by the sassy outspokenness of the daughter (me), and the European restraint of the mother (my mother), lay the great secret: What went on there? My mother held on to her silence with all her might, and I was afraid to ask. From the depths of the night, I heard the sounds of madness. Amid the darkness, I heard the endless, steady rhythm of her footsteps. This is how I learned the secrets of Auschwitz” (interview, 2000).

The first time her mother alluded to the sexual abuse she had suffered during the Holocaust was when Yosef was in the fourth grade. The incident is carved deep in her memory. In preparation for Holocaust Remembrance Day, she and her twin brother were told by their teacher to ask their parents what had happened in the Holocaust. “So we asked Mother and she said: ‘I will show you what happened,’ and she got up on the table, pulled down her pants, stood in her underwear and made noises … and we drank red wine and more wine and she danced. It wasn’t a pretty dance; it was frightening. Suddenly Father walked in and yelled at us and at her: ‘What have you done? Never ask what happened.’ And I went into a deep silence.”

In 1994 her mother died, and it was only a year later that she began to address the subject in a series of prints entitled Homage to Mother. In the first work, we see a naked woman sprawled on the floor, her legs spread open and on them a large blood stain spilling onto the floor. Her hands lie helplessly next to her body and she has no facial features. Her abdomen is bulging in an allusion to the potential consequences of the rape that has just taken place. In the upper left is a male wolf howling, with an erect, highlighted male organ—an image that suggests power, control, and, in this case, the triumph of the “kill” as well. The use of a wolf to represent the Germans is neither random nor disingenuous; the artist chose a beast of prey as a means of conveying the violence and hatred of the Germans. The image as a whole expresses severe violence and humiliation.

The second work contains all the elements of the first except that this time the blood stain has spread and is smeared violently across most of the workspace. On the left, we see two wolves, one above and one below, and they too are howling, and their sex organs are erect and accentuated. In the upper righthand corner, the artist writes: “The German yelled at her to climb up on the table, and she thought she heard a softness in his tone.” The addition of the second wolf heightens the sense of violence and humiliation and alludes to the possibility of group rape, while the caption recalls the childhood scene engraved in the artist’s memory. The work stresses the polarity between female victim and male aggressor, in this case a helpless Jewish woman and the all-powerful Germans.

In this series, the artist confronts her mother’s past from the perspective of a mature woman and mother. By “reenacting” the event, she attempts to make up to her mother for her thoughtless and insolent behavior as a young girl. At the same time, however, one cannot disregard the fact that the woman in the pieces is devoid of facial features. We can assume that such exposure was too difficult for the artist; or alternatively, she may have wanted to offer a personal portrayal within a general context. The emotional power of all the works in this series is expressed in a simple manner, via black outlines and splashes of reddish-brown color.

Replacement for the Dead

Even as the artists of the second generation addressed the trauma of the Holocaust transmitted to them by their mothers, they were also expressing the weight of the burden passed on to them by their parents, who saw them as a substitute for their loved ones who had perished.

Nazi ideology set as its goal the task of fighting the Jewish “anti-race” and obliterating it so totally that it would have no chance of continuing. After the Holocaust, many survivors considered the act of starting a family and having children to be a true victory over the Nazis, their ideology, and their deeds. Thus, the children of the survivors, who represented the physical and cultural continuation of the Jewish people, became a symbol of triumph. Survivors of the Holocaust saw their children as a path towards their own restoration and a way of injecting new meaning into their lives. They placed great hopes in their children, seeing them as compensation and replacement for their family members who had died. As Nava Semel writes: “Where did her mother draw the strength to conceive again? Her third child. And how Mama used to deceive her. Every birthday she told Daphna: ‘You’re my only one.’ But she was a replacement for the earlier children. Why didn’t her mother say: ‘You’re the only one I have left. I brought you into the world so that I wouldn’t forget my previous ones’?” (p. 60).

Many survivors named their children after those who had perished in the Holocaust, primarily out of desire to remember the dead and keep them alive, as it were. There was also an unspoken expectation that the children would serve as a replacement for the dead family member. Thus, the members of the second generation were often born into a situation wherein the name they carried represented the identity of someone other than themselves; at the same time, they grew up with the sense that they were assigned the task of replacing those who had died. This led them to a situation of dual or multiple identities coexisting simultaneously; in other words, they functioned both as themselves and as the family member whose name they bore. Although numerous psychological studies have explored this phenomenon, which is itself an indicator of its prevalence, it is interesting that Mira Hermoni-Levine (named after her sister, the daughter of her father from his first marriage) is the only second-generation woman artist in Israel to address it in a series of drawings entitled Mira A and Mira B (1992–1994).

During her childhood, Mira Hermoni-Levine heard only few and disjointed stories about her family members who had perished. Despite this, she internalized the sense of loss that was transmitted to her. In her words: “I grew up amid silence without answers, with much loneliness and fantasy” (interview, 1998). Hermoni-Levine was born in 1948, the only daughter born after the war to a father who had been in hiding and lost his wife, his son Osya, his daughter Mira, and other family members. As she recounts: “The details of what happened to them are unclear to me. When there was [still] someone to check with, I didn’t want to check. And now that I want to check, there is no one to check with. I am left with a very large and obvious ‘black hole.’” Her mother came to pre-State Palestine from Europe in 1933, leaving behind her parents, a twin brother, and three sisters who failed to make it to Palestine in time and were all slaughtered and buried in one large pit. Only one sister, whom she managed to convince to follow her to Palestine, was saved, and the artist was left with only photographs of the rest of her family. Hermoni-Levine’s father came to Palestine in 1946, met her mother, and they married and lived in Tel Aviv. Her father died when she was eight and a half years old.

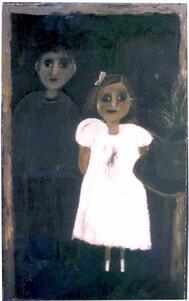

Hermoni-Levine created the Mira A and Mira B series after producing a number of paintings in the early 1990s in which she depicted the ghosts of her dead family members. The series is based on stories that she heard from her father and a single photograph that he managed to save, showing her brother Osya and sister Mira, who perished in the Holocaust. Mira A is her sister who died, and Mira B is herself. The series begins with a drawing of Osya and Mira A (fig. 11), both of them portrayed against a black backdrop with a frame, standing next to a table on which there is a plant. Osya is shown in dark clothes, standing slightly behind his sister Mira, who is highlighted by means of her bright white dress, the ribbon in her hair, and her white socks. The artist next portrayed Mira A alone, this time as very similar to both the figure in the photograph and the artist herself the way she looked as a child. “Her image is drawn from an inner reservoir. She looks like me in the paintings. She is a mixture of Osya, Mira and me. Every time I look for Mira, it brings me to another Mira. In this way, all the portraits of Mira were born,” says Hermoni-Levine.

In the next painting in the series, the artist drew a self-portrait as Mira B, in which she strongly resembles Mira A and is dressed in the same white dress with the same hairstyle and ribbon in her hair, of which she says: “I was six years old and they wouldn’t answer my questions, but they dressed me up in an organza dress, with a ribbon in my hair, white socks, and patent leather dress shoes” (Ma’or, 27; interview, 1998). The difference in both depictions lies in the background: In the portrait of Mira A, the background is smeared and blurry, suggesting that this figure has a vague, unclear past, whereas the background in the depiction of Mira B consists of the interior of a room, blurred but with hints of furniture and a picture on the right and something that looks like a doorway behind the subject; the feeling conveyed here is that the subject is in an actual setting.

Hermoni-Levine felt that her sister was such a dominant presence within her that at times there was no distinction between them. In one of the paintings in the series, she portrays an imaginary encounter between the two Miras in an attempt to communicate with the dead sister she never knew. The artist portrays her sister, Mira A, against the background of a room containing a window, a table, and a picture on the wall. She is wearing a white dress exactly like the one shown in paintings 11–12. By contrast, she presents herself as a young girl standing with her back to the viewer and wearing a brown dress, as if to emphasize the fact that Mira A looks as she did when she died whereas she, Mira B, grew older and changed. The feeling conveyed is that Mira B has “transported” her dead sister to the world of her childhood, in her parents’ home, so that she can meet her; but an actual encounter does not take place as there is not even eye contact between them. Mira A is looking straight ahead and meeting the eyes of the viewer, while Mira B’s expression remains hidden since she has her back to us in an effort to hide her turbulent emotions.

In another work in the same series, Mira A from “there” and Mira B from “here” are portrayed standing next to one another against the backdrop of the same interior as in the previous work. Here too, Mira A is shown in a white dress, but this time she is standing atop the table while Mira B is standing beside her, wearing a blue dress. The figure of Mira A is frozen in time, portrayed as she appeared before her death, in contrast to Mira B, who is living, growing, developing. Although the artist positions the dead sister on the table, she still looks like a small girl; perhaps this emphasizes even more strongly the fact that her life was halted. By dressing the two Miras differently (in both these works), she underscores the feeling that Mira A is beyond life, particularly in her use of the white dress as a symbol of purity and pristineness, in contrast to her portrayal of herself in a brown or blue dress. (Although in her interview with the author, she recounted that her parents would dress her in a white dress like that of her sister because they saw her as a replacement for the dead sister, we see that when she grew up and matured, she stopped wearing the white dress.) The dominant figure in both works is Mira A, since Hermoni-Levine wishes to emphasize that she is “summoning” her from the depths of her own self in order to confront the existence of Mira A within her.

In another picture, Mira B is portrayed as a young woman who has matured and changed. The color of her hair is now golden, and she is sitting facing a mirror, with her back to the viewer and her image reflected in the mirror. Mira B is gazing at herself in the mirror in an attempt to comprehend what is happening inside her, where Mira A and Mira B both exist. Hermoni-Levine relies here on the longstanding tradition of employing a mirror as an artistic device. There are countless examples of a figure surveying itself (or its inner essence) in a mirror, with the image of the person reflected in the glass. The significance of the mirror is not uniform, but over time, special powers and qualities have been attributed to it, both positive and negative. One of the qualities that artists, including Hermoni-Levine, have made use of is the mirror’s ability to serve as a link between the human subject and its representation. For the artist, the mirror serves as a medium of self-discovery in the encounter between man and his image that can reveal the hidden truth of the subject gazing in the mirror—a glimpse into the soul, far beyond the simple reflection of the image.

Hermoni-Levine, who found it difficult to convey what takes place within her and did not enjoy explaining her pictorial series, simply stated repeatedly: “I am the girl ‘in place of.’” Her paintings are an excellent example of the anguish of the second generation, who struggle with another person existing inside them; despite their desire to free themselves of this figure, their conscience does not permit it.

Memorial Candles

In contrast to the responses described above, some members of the second generation have taken upon themselves the task of remembering and perpetuating the Holocaust as a continuation of their parents’ experience. In many families of Holocaust survivors, a particular child is chosen to serve as a type of “yahrzeit (memorial) candle” for those family members who perished. (The term was coined by Dina Vardi to refer to the members of the second generation, whom she studied in her book Nos’ei ha-Hotem [Marked for Life]; an entire chapter is devoted to the children’s designation as “memorial candles” for the dead.) In the same vein, the child becomes a link between the past of the parents, which was obliterated, and the present and future of herself and her parents. To these children is assigned the task (whether implicitly or explicitly) of filling the actual and emotional vacuum left in their parents by the Holocaust, and additionally, of recreating and carrying on the family that was lost, thereby enabling the continuation of the Jewish people. Thus these “memorial candles” live simultaneously in a dual reality: in the present, as young people building their personalities and their lives, and in the past, laden with the traumatic experiences of their parents.

As early as the mid-1960s, Rivka Miriam, for example, chose to employ the image of a candle to represent herself in Self-Portrait (1964–1965). She depicts the outlines of her face, but in place of facial features on the right side is just a face with a large, protruding eye holding a terrorized expression, and a line across its face suggesting a nose and sealed mouth; on the left side, she places a candle with a flame. The feeling conveyed is of a twofold identity: one arising from the past, and the other living in the present as the keeper of the flame in the form of the burning candle. The artist depicts a figure from the past who exists within her, bearing a frightened look and a large eye, and combines it with the role she has taken upon herself, to serve as a “memorial candle” for the dead. As she states: “I have always felt Rivka and Miriam within me [the two relatives she was named after], not at my expense, not as if they are my own ‘self,’ but as if I have my ‘self’ and it is very present yet it also draws its power from them” (interview, 1988). Her words, and this work, serve to illustrate the fact that two elements coexist simultaneously within her personality.

Miriam Neiger-Fleishmann, named after her father’s daughter from his first marriage, who perished at Auschwitz, also feels a duty to explore this theme in the name of her sister and the other members of the family who died in the Holocaust. She was born in Slovakia in 1948 to a father who had lost his first wife and a daughter named Miriam, and a mother who had lost her parents. Her own parents married in Slovakia in 1946 and immigrated to Israel with the infant Miriam in 1949. Neiger-Fleishmann’s parents spoke little of their past, and her mother repeatedly told her: “Leave my dead alone.”

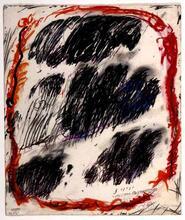

In her work Candles (1974–1975), Neiger-Fleishmann depicts two lit candles that appear as though they are emerging out of flames; one of the two candles is portrayed with facial features. “We are two sisters,” says Neiger-Fleishmann, “but only I take an interest in the Holocaust and the family history. My sister is less interested. I’m the one who is preoccupied with the Holocaust” (interview, 2000). Neiger-Fleishmann portrays her younger sister and herself as burning candles, the continuation of the family that survived; by their very existence, they have become the keepers of the flame. The turbulent background represents the Holocaust past of their parents. The candle with facial features symbolizes the artist, emphasizing the fact that it was she, of the two sisters, who was chosen for the role of memorial candle. “The inner torment of our parents passed to us…We are the children of survivors. ‘Survival’ is a key word in my life” (interview, 2000).

By personifying the candle with her image, she is underscoring the fact that she is the surviving ember that carries the remembrance of the past and perpetuates the memory of the dead and of her parents’ experiences in the Holocaust. The happy expression on the face in the candle, and the fact that the candles resemble festive birthday candles, give the viewer a false impression and distance the work from the meaning and the message that the author wished to convey regarding the acceptance of the role of “memorial candle.” A possible explanation is that this is one of Neiger-Fleishmann early works; as such, it is marked by a certain innocence and directness, both in the choice of the obvious image of the candle and in its simple composition.

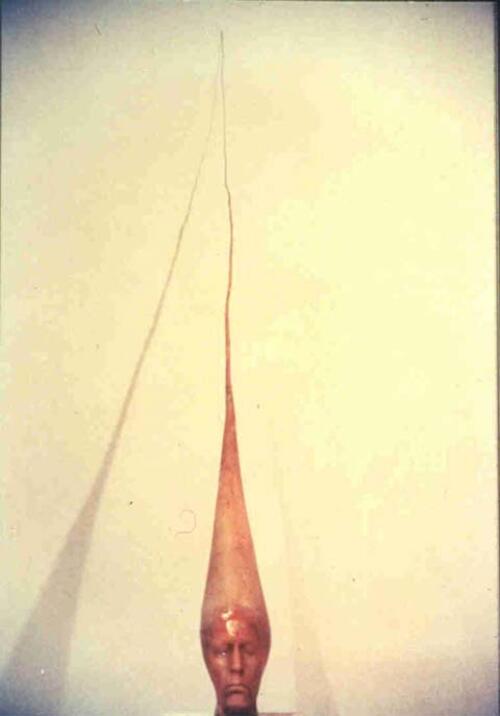

In contrast to the direct artistic expression of Rivka Miriam and Neiger-Fleishmann, Dvora Morag offers an oblique portrayal of herself as a memorial candle in her work Witch (1996), part of a series entitled Self-Portrait. Morag was born in Israel in 1949, the oldest daughter of Holocaust survivors. Her mother, a native of Poland, was in the Lodz ghetto, and later, Auschwitz. Her father, also from Poland, survived the ghetto, a forced labor camp, Auschwitz, and later, a “death march.” Upon their liberation, both were transported by the Red Cross to Sweden, where they met and later married. Since her parents’ stories were fragmentary, Morag filled in the missing information by reading. In 1990, at the start of her artistic career, when she was studying drawing/painting and printmaking at the Midrasha School of Art, Morag began to openly pursue the theme of the Holocaust and to confront what was taking place inside her. In 1996, while working on the Self-Portrait series, the subject of the Holocaust emerged indirectly in her work Witch, a sculpture cast in polyester resin. Morag produced a disembodied head whose face is her own self-portrait; in place of hair is an object sticking out that resembles a conical candle with a long, upright wick. Morag’s motivation for portraying herself in this manner is twofold: first, the desire to present herself as a female victim, reminiscent of the witches burnt at the stake; second, the veiled allusion, in the name of the work, to the fact that she sees herself as a witch, that is, as someone with a twisted inner world resulting from being a member of the “second generation.” (In an interview with the author, Morag stated that she was aware of the candle-like form, but not in the sense of a memorial candle. This meaning arose in conversation with the author, in particular when Morag noted the fact that she took it upon herself to remember what her parents went through in the Holocaust. She adds that the work is a reference to the fact that she sees herself as a victim of the past, of history, which is connected with her being a memorial candle.) Morag places the “candle,” her self-portrait, on the floor. Her intention is to force the viewer to look from top to bottom, thereby conveying the feeling that her image is highly vulnerable since the viewer can easily “harm” the portrait where it stands.

Although the phenomenon of members of the second generation serving as “memorial candles” is frequently cited in psychological studies, it is not often encountered in art, perhaps due to the fact that the image of a candle in this context is too obvious, too self-explanatory, or simply inadequate to the burden and responsibility of this task. It is interesting to note that those second-generation artists who have employed the candle in this manner are exclusively women.

In contrast to those who took up the task of remembering and memorializing through the explicit image of the candle, other second-generation artists have addressed the enormous vacuum and inner emptiness created by the loss of family members whom they never knew (often, they did not even know how they looked). They were moved to do so out of a powerful need to confront the dead and break free of their influence.

Conclusion

The subjects that have preoccupied women artists of the second generation serve to illustrate the role played by the Holocaust in their inner world, and the impact of their parents’ stories—told and untold—of life during the Holocaust. Through the expressiveness of their work, we are made aware of the profound effect of the trauma of the Holocaust that was transmitted to them, leading them to live with the dead, like Rivka Miriam; to unlock the “secret” of their mothers’ past, like Racheli Yosef; or to ask: How would I have acted had I been “there,” as in the work of Yocheved Weinfeld. We have demonstrated the difficulty of living with a name that represents the identity of another person residing within, coupled with the role of replacing the dead that was conveyed to the second generation, as portrayed by Hermoni-Levine in her series of paintings. And we have explored the manner in which women artists coped with the role of “memorial candle” that they took upon themselves with the aim of remembering the Holocaust and perpetuating the memory of their parents’ experiences.

English

Amishai-Maisels, Ziva. Depiction and Interpretation: The Influence of the Holocaust on the Visual Arts. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1993.

Axelrod, S., O. L. Schnipper, and J. H. Rau. “Hospitalized Offspring of Holocaust Survivors: Problems and Dynamics.” Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic 44 (1980): 1–14.

Barocas, H. “A Note on the Children of Concentration Camp Survivors.” Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice 8 (1971): 189–190.

Epstein, Helen. Children of the Holocaust: Conversations with Sons and Daughters of Survivors. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1979.

Fox, Tamar. Inherited Memories: Israeli Children of Holocaust Survivors. London: Cassell Academic, 1999.

Gampel, Yolanda. “A Daughter of Silence.” In Generations of the Holocaust, edited by Martin S. Bergmann and Milton E. Jucovy, 120–136. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982, 1990.

Hass, Aaron. In the Shadow of the Holocaust: The Second Generation. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Hollander, Anne. Seeing Through Clothes. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1975, 1993.

Kampf, Avram. Jewish Experience in the Art of the Twentieth Century. South Hadley: Bergin & Garvey, 1984.

Karpf, Ann. The War After: Living with the Holocaust. London: Minerva, 1997.

Kestenberg, Judith S. “Psychoanalytic Contribution to the Problem of Children of Survivors from Nazi Persecution.” Israel Annals of Psychiatry and Related Disciplines 10 (1972): 311–325.

Kestenberg, Judith S. “Survivor-Parents and Their Children.” In Generations of the Holocaust, edited by Martin S. Bergmann and Milton E. Jucovy, 83–102. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982.

Oliner, Marion M. “Historical Features among Children of Survivors.” In Generations of the Holocaust, edited by Martin S. Bergmann and Milton E. Jucovy. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982, 1990.

Prince, Robert M. The Legacy of the Holocaust. New York: Other Press, 1985, 1999.

Roskies, David G. Against the Apocalypse: Responses to Catastrophe in Modern Jewish Culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984.

Young, James E. At Memory’s Edge: After-Images of the Holocaust in Contemporary Art and Architecture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

Hebrew

Angel, Rachel. “Unique Wall-Drawings.” Ma’ariv, March 2, 1971, 23.

Ankori, Gannit. “Yocheved Weinfeld’s Portraits of the Self.” Women’s Art Journal (spring/summer 1989): 22.

Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Discussion of Yocheved Weinfeld’s You Look So Typically Jewish as part of a seminar on “Personal and National Identity in Art” led by Gannit Ankori, 1997.

Israel Museum. Yocheved Weinfeld (catalogue). Jerusalem, June-July 1979.

Joseph Constant Sculpture Gallery. Dvora Morag: Self-Portrait (catalogue). Ramat Gan: November-December 1996.

Levita, Dorit. “The Close and the Estranged.” Haaretz, June 15, 1979, 24.

Ma’or, Chaim. “A Knife Probing the Past.” Davar Rishon, April 5, 1996, Davar ha-Shavua section, 27.

Mor, Yael and Bar-On, Dan. “On the Seeming ‘Sabra-ness’ of Children of Holocaust Survivors: Biographical-Narrative Analysis of One Interview.” Sichot, vol. 11, no. 1 (November 1996): 37.

Semel, Nava. Hat of Glass. Tel Aviv: 1985, 1998.

Vardi, Dina. “Memorial Candles.” In Nos’ei ha-Hotem. Jerusalem: 1990.

Interviews (Hebrew)

Hermoni-Levine, Mira. Interview by author. Jerusalem: December 1998.

Miriam, Rivka. Interview by author (and visit to parents’ home). Jerusalem: December 14, 1988.

Morag, Dvora. Interview by author. Tel Aviv: May 23, 1999. June 1, 1999. August 30, 2000.

Neiger-Fleishmann, Miriam. Interview by author. Jerusalem: June 1, 2000. July 27, 2000.

Weinfeld, Yocheved. Interview by author. New York: September 19, 1997.

E-mail correspondence with Yocheved Weinfeld: December 2001-January 2002.

Yosef, Racheli. Interview by author. Tel Aviv: May 7, 2000. Tnuvot, May 24, 2000.