Sarah Rodrigues Brandon

The ivory miniatures of Sarah Rodrigues Brandon and her brother Isaac Lopez Brandon (1792-1855) are among the rarest portraits of Jews at American Jewish Historical Society, as they are the earliest known depictions of multiracial American Jews. Today, multiracial Jews make up about 12% of the U.S. population. Sarah’s history provides a unique opportunity to better understand the early lives of racially ambiguous Jewish women. Jewish women with African ancestry often faced prejudice from society in general and from European Jews. Ultimately Sarah triumphed against these prejudices and obtained privileges for herself and her children. Other women, however, were not as lucky and faced more difficult lives as second-class citizens.

Early Life in the Caribbean

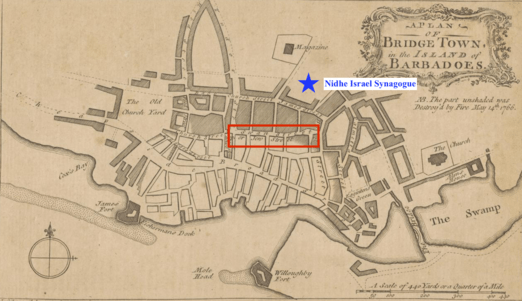

Sarah Rodrigues Brandon Moses’s life began at the end of the eighteenth century on the island of Barbados in the main port of Bridgetown. After Curacao, Suriname, and Jamaica, Barbados was home to one of the largest Jewish communities in the Caribbean. Although there had originally been two synagogues on Barbados, the one to the north in Speightstown had been destroyed by the time of Sarah’s birth. Most Jews lived in Bridgetown in the blocks near the Nidhe Israel Synagogue.

Sarah was born into the heart of this community, because at the time of her birth, her mother Esther Gill was enslaved by Sephardic Jew Hannah Esther Lopez. Also owned by the same family were Sarah’s brother Isaac Lopez Brandon, grandmother Jemima Gill, and great-grandmother Deborah Lopez. Sarah’s father, Sephardic Jew Abraham Rodrigues Brandon was a friend of the Lopez family. Because Esther was not born Jewish, Sarah was baptized Anglican shortly after her birth. Converting to Judaism in Barbados was not an option for the family. Conversions were extremely rare on the island, and there are no known instances of people with any African ancestry converting to Judaism at the Barbados synagogue during this era.

The Lopez-Gill family were not the only people of color in Bridgetown with Jewish ties. Their owner Hannah’s son had several “natural” children by free women of color who lived near Hannah’s house on Swan Street, also known as “Jew Street.” Other people of color with Jewish names lived nearby, such as Hester Lindo, Ruby Ulloa, Princess Castello, William Nunes, Finella Abarbanell, Esther Massiah, and Sarah de Castro. Some bore Jewish names because they or their ancestors had been enslaved by Jews, others because they had Jewish ancestry. Both Jews and free people of color in Barbados lived primarily in Bridgetown, and they often lived and worked on the same streets.

Sarah’s life might have been like that of many of the enslaved people in the port town were it not for two unusual events in 1801. First, Sarah’s father Abraham purchased Sarah and her brother from Hannah Lopez and then paid the church to allow them to go free. It would be the beginning of a close relationship between Abraham and his children. Over time, Abraham Rodrigues Brandon would become the wealthiest Jew on the island and parnas (president) of the Nidhe Israel synagogue. Throughout his lifetime, Abraham would support Sarah and Isaac financially, defend them in the synagogue, and treat them as his close confidants. The same year Sarah and Isaac were manumitted, Esther’s white father George Gill died and left Esther and her three brothers one of his houses and a small amount of money. Shortly before his death, George purchased Jemima from Hannah Esther Lopez. While he didn’t free Jemima in his will, he did make sure that she would be comfortable and wouldn’t have to live out her final days working for the Lopez clan. These changes radically altered the fortune of the Lopez-Gill family.

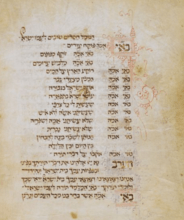

Freedom wasn’t enough, though. Around 1811, Sarah travelled to Paramaribo, the main port in nearby Suriname, a South American colony on the Caribbean Sea that had the largest multiracial Jewish community in the Americas and more liberal policies regarding race. Sarah and her brother appear both in the 1811 census and in the minutes of the synagogue where Isaac underwent a formal conversion before being circumcised. While women’s conversions often went unrecorded, later records suggest she also underwent a conversion while in Suriname. After returning to Barbados, Isaac became involved in the Nidhe Israel synagogue. Over the next five years, he found himself at the center of a heated debate about who and what was a Jew. Family ties and formal conversion weren’t enough.

Life in London and New York

Around 1815, Sarah left Barbados once again and travelled to London to attend an elite Jewish school, most likely accompanied by her father. Jews from Barbados often made the passage back and forth to London, for commerce, schooling, or marriage. A formal Jewish education was just as important for elite Sephardic women as it was for men. London presented Sarah with a new world of opportunities and connections. While in London, she had a small ivory portrait made (see above). In it, Sarah is beautiful and wide-eyed in a white empire-waist dress, her hair lifted high in a Grecian knot. The portrait was an intimate gift to the man she would marry—Joshua Moses, a handsome and well-connected Jew from Philadelphia and New York whom she met in London. Sarah brought to the marriage elite Sephardic lineage, and her father fixed on her a dowry of £10,000, a sum that would be worth roughly thirty million dollars today. This combination made Sarah one of the most eligible Jewish heiresses in London. In March 1817, Sarah married Moses at London’s Bevis Marks synagogue in London. Although the witnesses were aware of Sarah’s “natural” birth, her cachet as a member of the Portuguese Jewish nation still trumped Joshua’s Ashkenazi ancestry.

Shortly after her marriage to Moses, Sarah made the slow journey back across the Atlantic Ocean and settled in New York, where she remained until her death in childbirth in February 1828. When Isaac found himself cast out of the Barbadian synagogue, he joined her in New York and became Joshua’s business partner. Even though Joshua and many prominent members of the congregation had gone to school with Sarah and Isaac’s former slave owner’s grandson, neither of the Brandons were ever treated as less fully Jewish than any other members of the congregation. They were welcomed into the elite social world of the synagogue, and Isaac became a full voting member of the congregation. With the help of fellow congregants, he also became a U.S. citizen. Before she passed away, Sarah bore ten children, eight of whom lived to be adults. Her offspring would become Civil War heroes, one of America’s most famous early Jewish doctors, and a parnas of Congregation Shearith Israel. Another son married the granddaughter of Gershom Mendes Seixas, the congregation’s most beloved Rabbi.

Conclusion

Sarah Brandon Moses’s portrait is one of the few glimpses into how Sarah wanted to be seen by others. Like Maria Louisa de Hart, who appears in a 1846 daguerreotype of from Suriname, Sarah had both Jewish and African ancestors and was the daughter of a leader of an early Jewish congregation. Unlike Maria Louisa de Hart, however, Sarah Brandon Moses was fully recognized by Jews at the time as a Jewess and was an active participant in several early American Jewish communities.

“Barbados Church Records, 1637-1887," Barbados Department of Archives, Bridgetown, Barbados.

Deed Hannah Esther Lopez to Abraham Rodrigues Brandon (1802). Barbados Department of Archives, Bridgetown, Barbados.

Fuentes, Marisa J. Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018.

Hoberman, Michael, Laura Arnold Leibman, and Hilit Surowitz-Israel, eds. Jews in the Americas, 1776-1826. New York: Routledge, 2017.

Leibman, Laura A. The Art of the Jewish Family: A History of Women in Early New York in Five Objects. New York: Bard Graduate Center, 2020.

Leibman, Laura A. Once We Were Slaves: The Extraordinary Journey of a Multi-Racial Jewish Family. New York: Oxford University Press, 2021.

Leibman, Laura A. “Using Technology and DNA Genealogy to Solve Historical Mysteries,” Heritage Magazine. (2015): 19-21.

Leibman, Laura A. and Samuel May. "Making Jews: Race, Gender, and Identity in Barbados in the Age of Emancipation." Jewish American History. 99.1 (2015): 1-26. doi:10.1353/ajh.2015.0010.

Marriage License of Joshua Moses and Sarah Rodrigues Brandon (March 17, 1817), LMA/4521/A/02/03/009, London Metropolitan Archives, London.

Minute books of the Mahamad of Nidhe Israel, July 4, 1820, LMA/4521/D/01/01/008, London Metropolitan Archives, London.

Nederlandse Portugees Israëlitische Gemeente in Suriname/Dutch Portuguese Jewish congregation in Suriname, The Hague, Netherlands (NPIGS).

“Population returns number 201-490 collected as required by the governor's proclamation of 17 October 1811,” CO 278/23, folio 389, National Archives, Kew, England.

Newton, Melanie J. The Children of Africa in the Colonies: Free People of Color in Barbados in the Age of Emancipation. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2008.

UJA - Federation of New York. “Special Study on Nonwhite, Hispanic, and Multiracial Jewish Households.” Berman Jewish Databank. June 2014.

Levy Books - St. Michael’s Vestry Books 1792-1801, Part 1, Barbados Department of Archives, Bridgetown, Barbados.

Welch, Pedro L. V. Slave Society in the City: Bridgetown, Barbados 1680-1834. Kingston: Randle, 2004.

Will of Abraham R. Brandon (1831), Barbados Department of Archives, Bridgetown, Barbados.

Will of George Gill (1801), Barbados Department of Archives, Bridgetown, Barbados.

Will of Isaac Lopez (1804), Barbados Department of Archives, Bridgetown, Barbados.