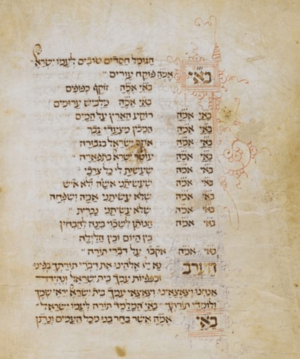

Early Modern Italy

Although families were notorious for making matches on the basis of finances, in reality some of these financial burdens were diminished to facilitate marriage and to protect family honor. To protect themselves from complications that could arise in the course of marriage, young women or their families often required the future husband to sign a prenuptial agreement. Despite careful negotiations, however, couples also acted on the basis of spontaneity, passion, or deceit, and parents might also force a woman, sometimes a girl, into marriage. To prevent such deviations from customary procedures, Italian rabbis tried to increase the number of witnesses to make arrangements binding. To meet individual needs, Jews engaged creatively with tradition, influenced by contemporary Catholic practice, throughout the marriage and when the marriage ended through death, divorce, or abandonment.

Introduction

Jews have lived on the Italian peninsula without interruption since antiquity. During the middle ages, the center of the Jewish population shifted from the south to the north. There, during the early-modern period, local Jews, joined by refugees from the Ottoman Empire and from Europe (including waves from French, German, and Iberian lands), were granted charters by local authorities to remain. They provided valuable services as moneylenders and merchants. Although this period saw anti-Jewish agitation by churchmen, the establishment of ghettos, the organization of new governmental bodies to supervise the Jews, and the development of local inquisitions, the fact that the Italian peninsula was not unified provided Jews with opportunities to leave one city-state to bring their services to another, a situation that gave rulers an incentive to ensure a measure of tranquility for the Jews in order to maintain their continued presence. The fact that French, German, Iberian, Middle Eastern, and local Italian Jewish customs were practiced near each other in the early modern Italian peninsula had a major impact on the range of options for Jewish women and their families.

To write the history of women in pre-modern times is a test of the historian’s craft: Few documents written by women exist; not many women are known by name; no statistical records for Jews exist that can be mined systematically; and historians have constructed misleading images of the role of women, both positive and negative, and often in the extreme. The study of Jewish women in a particular time and place offers an opportunity to reconstruct the structure of their lives and of the larger society in which they lived and to create a paradigm for the study of women in other periods and places.

Because those who are happily in love do not appear before law courts and seldom write poetry, the legal and literary record preserves the paper trail of unrequited love and relationships gone awry. Based on the latter, the historian must draw conclusions about the former, that is, determine how people lived happily ever after based on the records of those who did not. Legal and literary texts may serve as a mirror of reality rather than as a clear lens, reflecting life by offering an obverse image of it, with prohibitions often showing actual behaviors.

From the sources, which include rabbinic decisions, the archives of secular and religious councils, personal correspondence, religious guides, and belles-lettres, it is possible to find women’s voices, to see their actions, and to describe the dynamics of their lives using the imperfect models of the life-cycle, the stages of household formation and dissolution, and the categories of cultural and religious activities.

Following nineteenth-century historiography about Italy in general and early twentieth-century characterizations of Jewish life in particular, the sources can give the erroneous impression that there were more great Jewish women during the Renaissance than during the Middle Ages, which strengthens the mistaken notion that there was a liberating quality to the Renaissance. Yet the accomplishments of a few named women obscure the fact that most Jewish women lived lives quite different from those of both Christian and Jewish elites.

The sources provide a wealth of information about individual women, often unknown and even unnamed, and reveal how their lives were different from the paths prescribed for them in Jewish law and custom; how, despite the prescribed limitations, they enjoyed power, control, agency, and maybe authority; how they were affected by competing legal traditions and customs; and how those who tried to limit the activities of women often had to invoke extra-legal considerations.

Thus, the activities of Jewish women in early modern Italy were not the result of Renaissance values, any new status in the Jewish community, or the liberation of women, but rather are reflections of the regular give-and-take between traditional rabbinic texts, customs, the ongoing needs of Jewish families and communities, and the varying customs and habits of the non-Jewish environment, all of which, under certain conditions, women could serve or defy.

Therefore, trying to reconstruct the history of Jewish women from diverse sources is like trying to learn what is happening on the other side of a wooden fence. If we stop to linger in one place, often our vision is blocked; however, if we move along quickly, we can soon get a good picture as the images available through each crack merge in our mind. Thus, to see only ghetto walls, traditional prohibitions, and negative attitudes against women’s participation, indeed against any Jewish participation in society, is to block from view the reality of Jewish women’s involvement and the involvement of many Jews in their communities in Italy, both inside and outside the ghettos.

Household Formation

The main consideration in making a match and establishing a household was financial. Families were notorious for seeking out matches based on the wealth of the other family rather than the feelings of the people involved. In theory, there was a tremendous financial burden on both parties, especially on the woman’s side to raise a dowry, a major part of the sum necessary for establishing a family and a business. For this reason, less affluent Jews often found it difficult to make a match. In many communities the leaders or the prominent women took it upon themselves to help raise dowries for poor young women. In theory, the groom also provided a sum ritually stipulated in the marriage contract and an additional amount that was usually his main contribution, ranging from a quarter of the dowry to an amount equal to it. These sums became debts owed by the man or his estate to the woman in the event that he divorced her, died, or went to jail. In reality, however, because the sums were expressed in nominal amounts or ancient currencies while accompanied by exchanges of gifts, some of these financial burdens on the woman’s family were diminished in order to facilitate marriage and to protect family honor.

Negative terms, such as promiscuous, clandestine, adulterous, or rebellious, especially when applied by men to women, may in fact reflect a reality over which the (male) authorities had little control except to stigmatize it in strident language. What they are actually describing are women acting on their own volition at critical stages of their lives, which included how they selected their lovers before, during, and after marriage.

Jewish women, like their male co-religionists, were not always chaste prior to their marriage, if they ever married. Pre-marital sex, prostitution, and adultery were often a result of the impediments that life in general and Jewish law and custom in particular placed in the way of marriage or remarriage. These impediments included the inability to find a permanent mate, the lack of a means to secure a spouse, the difficulties in getting a divorce for women who had been abandoned or beaten, and the extended absence of one spouse. Extra-marital sex also resulted from the opportunities created by expanded households and congested living. Another sexual outlet for both Jewish men and women, despite all the legislation enacted to prevent it and the bodies established to monitor it, was relationships with Christians, including prostitution and marriage. Women could conceal their Jewishness (much more easily than men because of circumcision), convert, or extort dowries from their families in order to marry Christians.

Private relationships could include passionate acts of love or mere abandon, either of which could produce children, or at least intimate letters between the couple or gossip among the neighbors. Sometimes these relationships led to marriage, but not always. In the absence of witnesses, it was usually easy for one or the other party to change plans and break promises. The victims of such passionate relationships were not necessarily one or the other person involved, but rather the families and communities whose assets, authority, and honor were squandered by impulsive youth. In cases of children born out of wedlock, the records seem to show a greater tendency to protect the honor of men and to punish women. Women resorted to bringing the children to synagogue in order to shame the father into supporting them, to abandoning, or even to killing them. One man, on learning of his sister’s sexual activity, killed her to redeem the honor of the family, an act that their father justified using biblical and rabbinic texts.

To protect themselves from several types of complications that could arise during the course of marriage, young women or their families often required the future husband to sign a prenuptial agreement. These included provisions to ensure that in the case of his death his brother agreed to release her from any levirate ties (the obligation of a man to procreate with his late brother’s childless widow), to appoint her the beneficiary and executrix of his property, to agree never to take an additional wife while they were married, and to write her a bill of divorce if he became sick or set out on a dangerous journey.

An area for significant confusion in terms of both tradition and custom involved the intentions of a man giving gifts to a woman. In some Jewish communities, based on talmudic precedent, the receipt of a gift indicated that a woman was betrothed, and severance of the relationship required legal proceedings; in others, also based on talmudic precedent, a gift was simply taken as a sign of affection. Some women received gifts from several suitors who were wooing them at once, sometimes for their beauty or their wealth. Because of such competition, a man was reluctant to offer gifts to a woman who might spurn him for another.

Matches in Italy reflected a mixture of arrangements made by parents and spontaneity on the part of the couple. Usually fathers made the matches, but sometimes mothers or brothers did. Women were given the right to refuse, but cases of forced marriage took place. To prevent couples from acting on their own or under false pretenses, there was great concern that there be an adequate number of witnesses representing the woman and her family at each stage of the marriage process. Rabbis divided on the question whether the number of witnesses to a betrothal should be the talmudic pair or the subsequent requirement of ten males, reflecting a clear need for a greater number to enhance supervision of the proceedings.

Engagement involved no religious obligations between the couple, since it was of a contractual nature. In cases of broken engagement—an indication that either member of the couple could still have a change of mind—the side that broke it usually had to cover the expenses of the other side. The period of engagement could last a year or more, a further opportunity for heightened sexual, emotional, and financial ambiguity in the relations between the couple.

The Household

Information about life in the early-modern Italian Jewish household can be gleaned from the literature of rebuke and encouragement, such as sermons, commentaries, and polemics, which contained admonitions for the behavior of Jewish women. From these literary images it is possible to discern what women were doing and not doing. An example of this discourse is Eshet Hayil (A Woman of Valor) by Rabbi Abraham Yagel (1553–c. 1623), following verses in Proverbs that are recited in the home on Friday night. The speaker describes the dutiful wife serving her husband and doing everything necessary to make him happy and to preserve his honor. She is gentle, kind and calm, and she views him as master and lord appointed over her by God. The husband trusts his wife and places his house and possessions in her charge; she takes care of them and raises the children and may acquire the education necessary to fulfill these tasks. For the purpose of serving her husband, she is involved in business, which includes meeting merchants from abroad and being careful not to leave her house, where she carries out most of her transactions. She invests in land (unlikely for Jews at this time in Italy), gives charity, and spins, because any idleness may lead to lewdness. Her voice must never be heard in public. By contrast, the other woman, who is represented as most women, is bound by neither fear nor love, and she abandons not only her husband but also God. She is noisy and rebellious in the house, ventures outside, and stops doing her work. Soon, due to idleness, she is committing adultery and causing shame to her cuckold husband.

From such rhetoric, it seems likely that women did not always serve their husbands, preserve their honor, act gently, kindly, and calmly towards them, or accept their authority. Nor did they always adequately manage their houses, raise their children, and pursue business. It was sometimes necessary for men to threaten their wives with suffering and great pain to ensure their attentive service. The key to understanding Yagel’s fanciful description of the relationship between husbands and wives is that the education, wealth, and refinement attained by a woman must accrue to the honor, prestige, and position of her husband. Thus, many aspects of economic and intellectual life that were possible areas of empowerment for women were aspects of domestic life in which Yagel tried to present women as functioning for the benefit of their husbands and families.

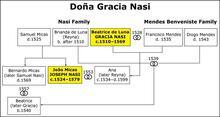

Indeed, rabbinic and archival documents show women, following medieval practice, regularly conducting businesses that involved financial power and serving as witnesses. Rabbis protested when women conducted business in public at fairs and at markets among Christians. Several prominent Jewish businesswomen in Italy were refugees from the Iberian peninsula who used their power for the benefit of the Jewish people: Benvenida Abravanel, Doña Gracia Nasi Benveniste, and Reyna Benveniste.

To limit the ostentatious display of family wealth, Jewish communities passed sumptuary laws, as did Christians. Among them, women’s clothing and public appearance were highly charged because they had the potential to reflect positively on the status of the entire family in the community and also provided the woman an opportunity to draw attention to herself, possibly at the expense of the honor of the family.

The early modern Jewish household was not always a nuclear family. There was two-way traffic that brought people both into the household (including various relatives, boarders, and servants) and out of it (including men’s working in another city, which often involved teaching, preaching, or business, or women’s travelling for business or family matters, or flight due to abusive treatment).

Servants were usually life-cycle servants, that is young, single Jewish adolescents of both sexes who lived with families and received training from their employers, sometimes enforced with physical chastisement, from the time they left home until they married. Their families paid for some of this, but the work was also an opportunity for young people to raise the funds necessary for marriage. For women, the education included all the aspects of housekeeping, such as sweeping, mopping, making beds, washing dishes, kneading, rolling, baking, salting, porging (an intricate aspect of Term used for ritually untainted food according to the laws of Kashrut (Jewish dietary laws).kosher (kasher) slaughtering), cooking, roasting, dancing, and playing music. Activities that some scholars have identified as a reflection of the liberation of Jewish women or the penetration of Renaissance culture into Jewish life, such as dancing, music, and porging, appear here as routine aspects of women’s housework, in order to enhance the honor of their families or necessary skills for women in cases where no men were around. When they married, servants could (re)join the same class as their employers—and parents. Employers tried to limit relations between servants because the marriage or pregnancy of a servant competed with their obligations to their empolyers. Employers, however, could also function as parents in arranging for the marriages of their servants, often to other servants. As a sign of affection, employers and servants left bequests to each other.

The inclusion of servants as part of the family did not produce a sense of taboo concerning sexual liaisons with them, by either the husband or the wife. One case that attracted attention involved a black, non-Jewish female slave (slaves from the orient were found among Jews, usually in port cities) who regularly went to the ritual bath so that her sexual relations with her Jewish owner would be religiously proper, highlighting the concern that ritual purity could be more important than sexual propriety. There were also cases of infertility in which Jewish men established surrogate relationships with female servants who produced children who were raised by the men and their wives as their own.

Some men, married or not, had mistresses with whom they had long-term intimate relationships that might produce children. Fathers made provisions for sons, naturale o bastardo (legitimate or illegitimate), to receive an inheritance. Other men, after ten years of marriage in which no children were produced, took a second wife. The medieval ban of Rabbenu Gershom (ca. 960–1028) against polygamy did not cover such a circumstance, and some Italian rabbis also claimed that it was no longer in force after the year 1240, the end of the millennium on the Jewish calendar. In some instances, despite Catholic bans on second marriages and polygymy, before taking a second wife, Jews sought the approval of the pope, which, for a fee, was often granted. Other Italian rabbis wrote vigorously against polygamy, an indication that it remined a divisive issue.

The discourse about women who committed adultery reflects the tension between private emotional relationships, women’s agency, and familial and communal needs. Italian rabbis discussed the question of whether to punish a woman for adultery or not, but they found no easy or automatic answers. The reluctance of some rabbis was matched by the zeal of others for drastic punishments, and both positions were justified by what seemed to be definitive precedents from rabbinic literature. Thus, while traditions seemed to support two competing tendencies, the discussion was directed toward issues of Jewish survival, communal control, judicial autonomy, and group honor rather than simply matters of morality.

The arguments for not punishing an adulterous woman were accompanied by a tendency to deny that immoral acts took place and to avoid the issue altogether. One concern, based on rabbinic precedents, was that publicizing the assignation would disrupt the family and the community because it would call into question the legitimacy of the woman’s other children, perhaps even compelling her to escape the authority of the rabbis and the Jewish community by converting to Christianity and taking her children with her. Children born to married women not fathered by their husbands, might be quietly passed off as those of their husbands, if they had been in town recently enough to be responsible for the pregnancy. Rabbis realized that their authority to enforce the law and to discipline Jews was limited. They argued for curtailment of severe punishments in the name of communal self-protection and survival. Some went so far as to deny that Jews actually had the authority to try such cases and to execute drastic punishments, suggesting instead that the community bribe the woman accused of adultery so that she would quietly change her behavior. Other rabbis argued that they had the authority to punish a woman for adultery and that it was necessary to do so in order that she change her ways, cease leading Jews astray, and serve as an example to others. They felt that if, as a result of the punishment, she chose apostasy or death for herself or her children, the rabbis would be free of any guilt and should not be deterred by any subsequent choices she might make.

Difficult childbirth was another stressful aspect of marriage for which tradition offered conflicting approaches. One method used in especially difficult births was to bring a Torah scroll into the birthing room for the woman to hold as if it were an amulet, a practice Catholic women also followed with holy books. Some rabbis, however, condemned using a Torah scroll in this way for several reasons: they did not believe that it was proper to derive material benefit from the Torah by using it for magical purposes, they did not want a Torah scroll placed in the bosom of a woman whom they saw as a major source of impurity, they did not want women to have control over such matters, and they questioned whether the words of women could be trusted when they testified that the Torah scroll helped them. As in other matters involving tenuous rabbinic authority, it was suggested that the rabbis not raise objections so that the women would not be in a position of defying them. Alternative suggestions included lighting a candle for the woman to ease her discomfort or have a group of ten men, separated from her by a divider, pray with a Torah scroll in her room. Nevertheless, Hebrew magic books include formulas to meet women’s medical needs during birth and in related matters such as birth control, conception, abortion, and lactation.

Household Dissolution

Since according to Jewish law a woman could not initiate divorce, she could resort to trying to have rabbis force her husband to grant her a divorce either by imposing excommunication or by sanctioning a brutal beating. The legal grounds for forcing a divorce on a man were always extremely limited and usually involved a physically intolerant defect that emerged after the marriage and that interfered with sexual relations. As in so many other matters, rabbis were reluctant to use force because they often did not have the authority or the power to do so or they were afraid of the destabilizing effects of such an action. Rabbis justified their reluctance to act by expressing concern that forced divorce was not valid, and as a result future children would be excluded from the community and precluded from marrying other Jews (mamzerim), that women were making such charges because they developed an interest in another man, or that the abuse, such as charges of marital rape during menstruation, could not be verified by reliable witnesses. So, like their Catholic neighbors, rabbis in Italy preferred to reconcile the couple; if that failed, they sought to impose separation. Under such circumstances, to receive a divorce, women were usually required to trade financial concessions for their freedom. Only in extreme circumstances did rabbis consider forcing a man to divorce his wife.

In case of divorce, the prospect of repaying assets owed to his wife provided a strong incentive for the man to remain in the marriage, but the possibility of his wife obtaining such a sum as part of a divorce settlement did not always cause her to reciprocate his reluctance to divorce. If, however, it could be shown that she was the cause of the marriage’s dissolution due to her adultery or rebellion, she could lose her right to some or all of the assets, a reason that such charges against a wife might often have been negotiating strategies rather than actual events.

In marital controversies, Jewish women turned to the secular authorities and even Church officials for help extricating themselves from difficult marriages. It is also not unusual to find reports of conjugal strife in which women gained the advantage, left home, or were able to force their husbands out of the house. If, however, a woman fled her home, then she could be accused of rebellion or adultery and lose all financial entitlements even if her husband was violent.

One charge leveled by some women against their husbands was that the men were impotent, incapable of fulfilling their obligations to satisfy them or to produce offspring. Some rabbis were reluctant to grant such women an immediate divorce, probably because their ability to do so was limited, but they rationalized their inaction by expressing the concern that women would make such charges only because they had developed an attraction to another man. Some rabbis required that the women stay with their husbands for ten years, and only then, if no offspring were produced, might divorce be a possibility. Attempts were also made to blame the men’s impotence on the women, either because of the nature of their anatomy or their use of magic.

A few discussions of wife-beating appear in Italian rabbinic literature, literary texts, and archival material, but they do not indicate how widespread incidents of physical abuse actually were. A look at some of the limited evidence shows the relationship between women’s volition and men’s weakness and violence. Despite the subjection of women to restrictive legislation and rhetoric, the impression emerges that women who were beaten had exceeded the boundaries of what their husbands would accept, asserted their independence in religious, domestic, or sexual matters, or had simply incurred the wrath of an abusive husband for no reason. It seems men acted violently not when they were strong but rather when they were weak, or when they had no other way of influencing their wives or asserting power. In conformity with views in earlier rabbinic literature and in Catholic texts, Italian rabbis thus made a distinction between justified and unjustified violence against one’s wife. Physical chastisement, as opposed to what was defined as cruelty (ahzariut, saevitia), was considered a necessary component in a man’s treatment of his wife. Yet Italian rabbis could find precedents to support forcing a violent man to divorce his wife and give her the financial benefits to which she was entitled, usually based on rulings by rabbis from Islamic countries, where Jewish women could turn to secular courts for divorces; in Italy secular courts were rarely willing to engage with these cases, reflecting Catholic opposition to any divorce. In literary texts, men fantasize about killing or mutilating their wives, and uxorcide appears in archival documents.

When a man died, his wife needed protection from many threats to her freedom due to the social tensions produced by contradictions in tradition. The levirate union (yibbum), an ancient practice also mandated for Jews in the Bible (Deuteronomy 25:5-10), involves a situation in which a childless widow must produce a child with her late husband’s brother, although the Bible also contained a procedure to release him from this obligation (halitzah). That a dead man’s brother was married already did not negate his obligation to his childless sister-in-law and her need for release from him before she could marry anybody else. The levirate union was contradicted by a biblical commandment that men must not have intercourse with their sisters-in-law (Leviticus 18:16), providing the basis for a longstanding conflict in Jewish law and practice concerning which commandment took precedence. Levirate unions provided an opportunity for men to blackmail their sisters-in-law for a release. In such a situation, some rabbis claimed that a man could grant his sister-in-law release only by his own free will and not under duress, while others were willing to use force against him, another matter involving the question of the extent to which rabbis really had the ability to impose their will. Nevertheless, there were a few cases in which the widow and her brother-in-law, even if he were married, decided to create a union rather than to seek release. Levirate union was considered for many reasons. For kabbalists it was seen as a way to enable the transmigration of the late brother’s soul. For others it was a vehicle for the brother-in-law and the widow to share the estate and to keep it in the family, a simple way for the widow to ensure that she was cared for, especially if she was elderly. And for some, despite all their protests to the contrary, it was a sexual adventure on the margins of the forbidden—a chance for a man to engage not only in polygamy, but with his sister-in-law who was otherwise forbidden to him by the same Torah that commanded the levirate union.

Extortion by her brother-in-law was only part of the trauma a woman experienced when she lost her husband. Because of a statement in the Zohar that when a woman attended a funeral everybody there was at risk from attack by the angel of death, in some places women were not allowed into cemeteries to attend funerals, including those of their own husbands.

There was a tendency to look down upon women who remarried because of concern that they were seeking sexual satisfaction from other men or transferring their late husbands’ assets or children to another family. This was seen as an affront to the honor and finances of their late husbands and their families. The Church tried to eliminate remarriage, that is serial marriage or digamy. Jews tried to postpone it for a long as possible, and widows tried to escape such a fate, though if they did remarry they might lose custody of their children or control of their assets, which could occur even if they did not remarry.

One way in which Jewish practice tried to postpone remarriage was the attempt to prevent a pregnant or nursing widow or divorcée from remarrying before the child was two years old. The traditional assumption was that disregard of a fetus or a child by a husband who was not the father might, in the case of a pregnant woman, endanger the fetus during sex. If she already had a child under the age of two, intercourse might spoil her milk. If she sent the child out to a wetnurse, the child might suffer neglect or abuse. On the other hand, there was concern that if a widow felt she could not remarry for two years, she might be provoked to kill the child. To facilitate remarriage, divorced or widowed women were counseled by relatives not to start nursing so that they would not be considered nursing and would not have to continue, and they were thus free to remarry.

Generally, when a Jewish man died, his wife did not inherit his possessions but only what was due to her from her dowry, Marriage document (in Aramaic) dictating husband's personal and financial obligations to his wife.ketubbah, prenuptial agreements, and property that she brought into the marriage. These assets were held by the man’s family, and they might be reluctant to part with them, offering her sustenance instead of a cash payment or even withholding everything. To recover her due, a widow might turn to the courts, Jewish or secular, but in doing so, she ran the risk of losing anything to which she might have been entitled, and even being excommunicated for being presumptuous enough to make such a claim. Some rabbis opposed these limits placed on women’s access to justice and did act on their behalf.

Another way in which Jewish women acquired assets was when they received bequests and became the executrixes of estates based on a last will and testament made by their husbands or another person with a Christian notary, which did not have to follow traditional lines of patriarchal inheritance, although rabbis and Christian legal scholars raised questions about the validity of such testaments. Jewish women could also draw up a last will and testament to bequeath their assets as they wished. Jewish women left more testaments than Jewish men, a phenomenon also found among Christian women, indicating that more women than men were not willing to rely upon traditional lines of inheritance. When women made their testaments, they made choices that reflected their preferences among a wide network of relationships, including many women. They could show favor for one relative over another or for one child among many, and they could include or exclude their husband as they wished. Women made donations to the poor, hospitals, confraternities, and synagogues. They also kept some funds aside to provide for their own burial, usually near relatives, often their husbands. Thus, the testaments constituted an opportunity for a woman to give public reckonings of perceived wrongs by her husband and children or for her to recognize especially solicitous attention by others, including neighbors, friends, and children, often during her times of illness. These testaments serve as maps of community and family relationships, and the choices of giving were based on affection rather than law. With those around them aware of their ability to make such choices, women’s power was enhanced during their lifetime. Dictating in a mixture of Italian, Hebrew, German, Portuguese, and Spanish, the women testatrices had neither advanced writing ability nor any evidence of book ownership, except of prayer books. Books that did appear in the testaments were male assets, raising the question of the extent to which women were involved in intellectual, poetical, musical or other cultural activities.

Women and Culture

Although males tried to silence women who studied, wrote, sang, danced, or prayed, women did study, write, sing, dance and pray. Rabbinic opponents of women’s literacy were motivated, in part, by the traditional concerns of ensuring their domestic role, feminine qualities, and sexual purity, and by prejudices about women’s simplemindedness. Nevertheless, they saw some literacy as necessary in order for women to conduct religious life, run the household, supervise the family business, raise Jewish children, and enhance their husband’s honor. Evidence shows that some Jewish girls in Italy did attain a basic level of literacy. Moreover, some aristocratic Jewish women, aided by private tutors or parental teaching at home, attained advanced skills in Italian, Latin, and Greek, including poetry, rhetoric, and history, as they cited texts from authors as diverse as Terence, Cicero, Ovid, Boethius, Dante, and Petrarch; and in Hebrew, including Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah, Codification of basic Jewish Oral Law; edited and arranged by R. Judah ha-Nasi c. 200 C.E.Mishnah, Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmud, A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).Midrash, Jewish law, Moses ben Maimon (Rambam), b. Spain, 1138Maimonides, and The esoteric and mystical teachings of JudaismKabbalah. A few, sometimes identified as widows, taught; others, in association with their husbands at home, worked as scribes and in the publishing industry; a few were published authors, including Devorà Ascarelli, Sara Copia Sullam, and Rachel Morpurgo; and others, like Benvenida Abravanel, Doña Gracia Mendes Benveniste, and Reyna Benveniste supported scholarship and publication.

Further possible evidence of Jewish women’s literacy appears in Hebrew letters attributed to women authors or recipients, usually saved by teachers who specialized in Hebrew composition. Because these letters show signs of having been dictated, they could have constituted writing drills by teachers for male students. Nevertheless, even if these letters were part of imaginary exercises, they may reflect aspects of the education of young women.

In one such Hebrew letter, a young girl wrote to her father to ask for music lessons. She was not alone because other Jewish women in Italy became successful musicians. During the 1560s, a Venetian Jewish woman, known as una Madonna Bellina ebrea and as “Colonna de la Musica,” a pillar of music, enjoyed a reputation as a popular composer, player, and singer. In the early seventeenth century, Judith Trabotto (Trabot), the wife of Nathaniel Trabotto (1576–1658), a rabbi in Modena, received acclaim for her abilities to play the lute (kinor) and the viol or pipe (ugav) and to sing, including liturgical art music. The most prominent Jewish woman in music in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was Madame Europa, who worked in the court of Mantua as a salaried musician along with several other Jewish men and women, including her brother Salamone Rossi (c. 1571–c. 1630), an instrumentalist, a singer, and a distinguished composer of Jewish and secular choral and orchestral art music.

Jewish men and women studied dance, and they sometimes caused a stir by dancing together or with Christians, which upset Jewish and Christian authorities alike. Since they were unable to ban mixed dancing, leaders tried to limit it to holidays and weddings, and requested that women wear an apron (zifon) over their clothing so that they would be further protected from contact with men. Indeed, illustrations show men and women dancing together.

Religious Practice

In a strong critique of women assuming religious activities supposed to be confined to males, Yagel explicitly singled out for rebuke women involved in religious, mostly ascetic, practices such as daily prayer, fasting, placing ashes on their heads, wearing sackcloth, and denying themselves enjoyment of even the smallest earthly matters, especially pleasure. Even though he admitted that the intentions of these women were good and holy, these women had not fulfilled their obligations to God because their single-minded devotion to God was a dereliction of their duties to their husbands and their homes. A man will turn against his wife and hate her for taking such a course, he argued.

Women, nevertheless, sat in their own section of the synagogue, usually in the balcony. In one case, when women quarreled about their seats, seating assignments had to be issued that represented a hierarchical structure for the older, more educated women to lead the others. Women who sat at the head of the first several benches were designated as rabbanit (a title of distinction found in classical rabbinic literature for women who participated in rabbinic discussions), with the addition of their husbands’ names or their own, meaning that they may have acquired the title on the basis of their own learning. Next came women with the title of marat, madam, then those with the designation almanat, indicating a widow; the women who sat at the far end of the bench had the title kallat, the bride or betrothed, and were probably younger. The back rows were headed by women who had the title marat but not rabbanit. One woman had the title of shamashit, the female sexton. Elsewhere, one woman had the masculine job title of sheliah zibbur (representative of the community), and she functioned as did men who led the service.

Women’s segregation in the synagogue balcony did not mean that they silently accepted their position. Indeed, women raised their voices to protest unspecified offenses. Sitting together, they also joined together to curse men who had done them wrong and asked for vengeance against them. This protest illustrated to local rabbis the connection between women’s religiosity and their disobedience to their husbands. The rabbis denounced the men in the congregation because men should rule over their wives and not allow such disobedience.

Though women were denied direct access to the Torah during the service, they made the binders with which the Torah scrolls were wrapped. The Hebrew inscriptions on them, lavishly embroidered by women, identified them in relation with a man—husband, father, or even grandfather.

Two documents mention women in Italy praying while wearing Phylacteriestefillin(phylacteries), the traditional ritual leather straps on the arm and head usually associated with male religious practice. One describes—as a matter of fact—two women who wore them, like Michal, King David’s wife, who, according to rabbinic tradition, wore tefillin. The other document protests against women who wore tefillin and noted that Michal was an exception because she was the daughter and the wife of kings.

The use of liturgical Hebrew by some women is evidenced by the existence of a few manuscript collections of private Hebrew prayers specifically designed for Jewish women in Italy. The instructions before each prayer, however, are often in Italian, indicating that the women might have read but not understood Hebrew. These prayers relate to the rituals associated with women, especially baking Sabbath bread, lighting Sabbath candles, immersing in the ritual bath after menstruation, and marking transitions through the critical stages of pregnancy from conception to returning to synagogue after the child was born. In addition, translations of the Bible and of the worship service were made in Judeo-Italian, for the benefit of both women and men who did not understand Hebrew. The rituals specifically associated with women were also treated extensively in special tractates circulated in Judeo-Italian, Yiddish, or Italian.

Reflecting a small attempt for women’s inclusivity in Jewish worship, some sixteenth-century manuscript Hebrew prayer books for women include a revised morning blessing that, instead of the traditional “who has not made me a woman,” reads “who has made me a woman and not a man.” One rabbi and kabbalist felt the need to defend the traditional formula of the prayer, arguing that men should rejoice that they are not connected with servitude, the frivolity of women, and impure thoughts.

Jewish men, therefore, viewed the religious and cultural accomplishments of the women in their families the same way that they viewed their clothing. As they tried to control women’s manner of dress with sumptuary laws, they also tried to control their religious and cultural accomplishments. Such cultural and spiritual endeavors were highly charged because they could either reflect favorably on the status of the entire family in the community or provide a woman with ideas or opportunities that could hurt the honor of the family. The Jewish community was in the same dilemma as Catholic society in Italy: while some might try to limit women’s access to cultural and religious opportunities, at the same time women’s lack of education, especially illiteracy in Italian but also in more advanced subjects, would be counterproductive for their domestic responsibilities to their family.

Conclusion

The study of women in early-modern Italian Jewish history leads to a new sense of the nature of Jewish society itself. One of the key features of Jewish society that requires a significant modification is rabbinic authority. Italian rabbis often explicitly made their decisions in the spirit of the medieval Jewish view that later rabbinic authorities were more binding than earlier ones. Thus, it cannot be taken for granted that the Bible and the Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmud were the ultimate arbiters of Jewish experience. Rather, these texts were mediated by conflicting rabbinic views and Jewish customs. Rabbis regularly drew on the principle that custom takes precedence over law to ratify what had become common practice among Jews of their day. Most important was the fact that rabbinic authority was tentative. Limited by forces both within and outside the Jewish community, rabbis could make threats that they could not keep or refrain from making them in order to save face. Either way, they were weak, and ultimately it must be concluded that Jewish women were not protected by rabbis in Italy. It is impossible to suggest that in their subordinate position in the domestic sphere assigned to them women received protection. As the Jewish woman moved through each stage of her life—as a vulnerable child, a young woman starting a marriage and a family, a mother in the throes of birth, a part of a couple with a fertility problem, a married woman whose husband had taken up with another woman, a wife whose husband abused her, or a divorcée or a widow—she was at risk, and her success was due to the ability of her allies in her family to help her by using the system to her best advantage.

Therefore, the study of Jewish women in this period of history, as indeed in most others, leads to the conclusion that the day-to-day life of a Jewish woman was determined by an ever-fluid balance of what others wanted them to do, what others were afraid of them doing, and what women themselves wanted to do. There was neither a static position of Jewish women, nor did any woman (or any man for that matter) live solely by the tenets of religion. The heroic aspect of history was the daily struggle mounted by women whose very existence posed a challenge and a threat, as well as being a necessity, to the men in their lives.

Texts and customs, Jewish or other, influence social behavior without entirely dictating it. Despite their embeddedness in Jewish tradition and law, Italian Jews, like Jews of so many countries, were very much involved in local custom and law, especially when these served their needs better than Jewish options. Individuals, especially women, made decisions and followed strategies that were based on personal needs and affection rather than always on the dictates of law. The victimization of women, legislation against them, and patriarchal, misogynistic and sexist attitudes relate to the behavior and attitudes of men, not the agency, initiative, voice or power of women. Just as Jewish history was always more than the shortest distance between two massacres and Jewish life was more than the sum total of all the restrictions imposed on the Jews, so too a study of the life of Jewish women reveals that they created many more opportunities than allowed for by law.

Adelman, Howard Tzvi. Woman and Jewish Marriage Negotiations in Early Modern Italy: For Money and Love. New York: Routledge, 2018.

Weinstein, Roni. Marriage Rituals Italian Style: A Historical Anthropological Perspective on Early Modern Italian Jews. Leiden: Brill, 2003.