German Immigrant Period in the United States

Title page of Die Deborah, an influential American Jewish newspaper published in German for women, published in January 1901. The page reads, translated from German:

"Forward, my soul, forward with strength!

A German-American weekly to promote Jewish interests in community, school and home.

Founded in 1855 by Isaac M. Wise.

Published by a union of Jewish authors."

Courtesy of HathiTrust.

Like the men who immigrated in the same period, female German Jewish immigrants to the United States were generally younger and unmarried. Women who followed husbands to America or married once they had immigrated made their own sources of incomes, often through providing domestic services to other families and even opening small businesses. However, many female immigrants were widows and therefore likely to be poorer. Their struggles motivated women to create benevolent societies that aided the poor. These groups also encouraged people to continue participating in Jewish rituals, especially as the traditionally strict dichotomy between male and female changed in immigrant communities. Women began to attend synagogue more often and, through print journalism, portrayed themselves as the defenders of Judaism.

Reasons for Immigration

The period 1820–1880 has generally been considered the era of German Jewish immigration to the United States. In these sixty years, the bulk of the 150,000 Jewish immigrants who came to the United States hailed either from areas that, in 1871, would become part of a unified Germany, or from a range of other places in Central and Eastern Europe that later in the century adopted either the German language or various aspects of German culture. In these years, Jews came to America from Alsace, Lithuania, Galicia, Moravia, Bohemia, Hungary, Poland, and parts of czarist Russia.

Given the fluidity of European political boundaries in the nineteenth century, the volatility of language loyalties, and the absence of accurate immigration and census figures for this period in the United States, for women in particular, the term “German” may still be the most convenient, although not particularly precise, term by which to refer to this era in the history of Jewish immigration. Historical and popular writing consistently employ this term despite the misleading generalization implied in it.

Issues of gender and family shaped this migration from the Germanic regions, and from other parts of Central and Eastern Europe from 1820 to 1880. First, marriage became an increasingly remote option for both Jewish women and men from the poorer classes. In the 1820s and 1830s, a number of jurisdictions in the Germanic regions instituted limitations on Jewish marriage. Young Jews could marry only when a place became available on the community’s roster, known as the matrikel. These restrictions not only affected the absolute number of Jews who could marry, but also had implications for issues of economic class. Jews who could prove that they had a reasonable chance of earning a decent living could marry, while those whose prospects seemed dimmer were denied the right. This latter group was growing larger at precisely this point in time.

Secondly, the modernization of the economies of much of Central Europe severely undermined the basis of the traditional Jewish economy, particularly that of the poorer classes. Industrialization and improvements in production and transportation wiped out much of the need for the classic Jewish occupations of peddling and eliminated the businesses of other Jews who served as intermediaries between the rural peasantry and the rest of society. As such, the daughters and sons of the less-well-off Jews had to find other options for themselves. Thousands of young Jewish women and men migrated to America because they could not make a living in Europe or marry.

Immigrant Demographics

The migration to America began with young, single men, although unmarried women came in relatively large numbers as well, and in some cases, entire families joined the immigrant stream. The first phase of the move to America from any town or region began first with the young men. As a consequence, in the 1820s and 1830s in Germany, for example, Jewish communities saw female majorities developing, particularly in the rural districts.

This imbalance in the earliest years of the exodus from any particular German or other Central European town was only temporary. After achieving some economic stability in America, men frequently returned to their hometowns to find a bride. Other Jewish men in America relied upon the mails to propose marriage to a young woman from the home village, or they relied upon friends or male relatives who were journeying back to Europe, asking them to contract a match for them in absentia. Thus the years that saw the towns in Germany developing Jewish female majorities found the early American Jewish communities characterized in their formative years by male majorities. In most American Jewish communities, the majority of the women arrived later than their husbands, and communities endured some period of time in which a male—and bachelor—society characterized community life.

Despite the seeming masculinity of the early migration, a surprisingly large number of single women joined the migration, even in its earliest years. Women made up 45 percent among those who left the Bavarian town of Kissingen for America in the 1830s and 1840s, for example, whereas from all of Bavaria over the course of the 1830s, men and women emigrated in roughly equal number, 12,806 and 11,701, respectively.

Such figures obviously cannot tell the entire story, since some kind of time lag could have occurred between when the majority of the men and the majority of the women migrated to the United States. But importantly, Jewish women who emigrated came from the same classes and for the same reasons as the men. As daughters of the poor, they not only left to follow or meet potential spouses, but they too were victims of economic change.

Economic Patterns

Jewish women in Central Europe in the decades before and during the migration played a key role in the family economy. As the daughters and wives of craftsmen, they participated actively in producing and selling goods. Some women, among the somewhat more well-off, actually owned their own businesses independent of their husbands. Poor Jewish women in Europe had traditionally worked as domestic servants, while others sewed for a living with their families or on their own. Just as the economy had dried up for the men, in the more marginal rungs of the Jewish class structure, so it did for the women. These women had the same incentive to come to America as did their brothers.

The history of Jewish women in the period of the German immigration cannot be understood without an analysis of the particular economic niche that Jews came to occupy in the United States. Because so many of these immigrants were unmarried and arrived unencumbered by parents or children, they could take advantage of economic opportunities wherever they arose. While the small pockets of Jewish settlement that greeted them as of 1820 were limited to a few Atlantic coastal cities, the German Jews fanned out into almost every state and territory of the United States. They made their way through New England, the Midwest, the Great Plains, the South, and even the Far West, although they also settled in New York and Philadelphia and the other cities that already had well-established Jewish communities.

Although primarily going to agricultural areas, the male German Jews who “pioneered” and the women who joined them somewhat later did not do so as farmers, but as small-scale entrepreneurs ready to serve the needs of the rural population. Americans in the hinterlands had little access to finished goods of all sorts, since few retail establishments existed outside the large cities. Jewish men overwhelmingly came to these remote areas as peddlers, an occupation that required little capital for start-up and that fit the life of the single man.

In the large regional cities, Jewish immigrant men would load themselves up with a pack of goods, weighing sometimes as much as one hundred pounds, and then embark on a journey by foot, or eventually, if a peddler succeeded, by horse and wagon. So widespread was Jewish peddling that in 1840, 46 percent of all Jewish men made a living this way, and by 1845, the number climbed to 70 percent. Of the 125 Jewish residents of Iowa in the 1850s, 100 were peddlers. Memoir literature and biographical details of Jewish men who began their lives in America as peddlers indicate that most plied their trade during the week and on the Sabbath, they gathered together in the larger communities, in Jewish-operated boardinghouses, sometimes managed by the rare Jewish woman resident. In 1854, for example, a Mrs. Weinshank, ran a boardinghouse in Portland, Oregon—five years before statehood—which catered to the Jewish peddlers of the Pacific Northwest.

The concentration of Jewish men in peddling had implications for women and for the process of family and community formation. First, peddling as an occupation sustained the singleness of the migration and the process by which young men migrated first, followed by women later, depending upon the speed with which the peddler could amass the requisite capital to become a shopkeeper. Typically, these immigrant peddlers decided to marry at the point at which they had graduated from peddling to owning a small store, either in the hinterlands itself or in a larger city with a more substantial Jewish community already in place. The Jewish man who returned to his Bavarian or Bohemian hometown to contract a marriage frequently made arrangements to find willing women, often the sisters or cousins or friends of his bride, to come back to America as the fiancées of the many eligible Jewish bachelors there. Since the migration of this period flowed continuously, Jewish communities, particularly the smaller ones, tended to experience a dynamic in which single men predominated, followed by the arrival of women, often to be followed by a new influx of single men, who would shortly thereafter be joined by women.

The Jewish women who came to America in the years 1820 to 1880 came from the exact places and classes as did the men. Despite the absence of any kind of statistical evidence, it is possible to say that these women came to America not only to marry but to work. Their exact number cannot be ascertained, however, because most of these women labored in family stores and shops. Numerous contemporary commentators described women in these roles. The smaller the store, the more likely wives, and then daughters, worked. Indeed, men may have timed their marriage with getting off the road and into a shop precisely in order to have the services of a wife to operate the business jointly with them.

Some memoirs describe men in a family, the husband, and his brothers, continuing to do some peddling, while the wife and other female family members sold from behind the counter, offering the family the possibility of a diversified operation. Jews predominated in the sale of dry goods in small and large communities. These dry-goods stores emphasized the sale of clothing, and many of the Jewish men and women who owned and operated these stores also manufactured the clothes. The success of stores in which clothing was both made and sold along with other kinds of miscellaneous goods depended equally upon the labors of men and women, adults, and children. A man could not really envision such a store without a family.

Jewish women in this period worked not only as the wives and daughters of petty shopkeepers, but in other ways as well. When husbands died, wives often carried on family businesses on their own. This widespread phenomenon was particularly significant, because given the nature of the migration process, men tended to marry women significantly younger than themselves, thus making the probability of widowhood higher and accentuating the need for women to be self-supporting.

Married women and widows appeared in many community and family histories as operators of boardinghouses. Recognizing the need for feeding and lodging the stream of single men migrating to America, Jewish women turned their homes into businesses. Boarding operations supplemented income from other family enterprises or provided the family’s sole support. These Jewish women combined their domestic activities of cooking and cleaning with the imperative for making a living.

Jewish immigrant women, married and single, also sometimes created their own businesses, in essence keeping alive what seemed to have been a long-standing European Jewish tradition. Generally, these women ventured into the same kinds of small businesses that Jewish men did. A few examples from a number of communities demonstrate this pattern. Amelia Dannenberg came to San Francisco with her husband in the 1850s from the Rhineland and launched a children’s clothing business. By the 1870s, she branched out to manufacture men’s and women’s clothing as well. The mother of Judah David Eisenstein, a Hebraist, opened a dry-goods store on New York’s Lower East Side in 1872 so that her son could engage in full-time study.

As late as 1879, it became clear to the Lissner family in Oakland, California, that the family could not survive on husband Louis’s income as a pawnbroker. So, the wife, Matilda, decided to raise chickens, and she peddled the eggs on the city streets. Bella Block had learned millinery work in Bavaria before immigrating, and in Newark, New Jersey, she opened her own shop prior to marriage and continued to operate it afterward. She and her husband also jointly ran a grocery store. These and other examples from almost every Jewish community in the United States make it clear that women played a crucial role in the family economy, and indeed such an economy could not have existed without their input.

Philanthropic and Communal Organization

Not all Jews, men or women, did well economically, and Jewish women in particular suffered from financial distress and insecurity. Their high rates of widowhood caused a good deal of that distress. Indeed, in most communities, widows made up a disproportionate share of the Jewish indigent. These included both those with and without children to raise. Jewish children turned up in orphanages more often if they had lost fathers than if they had lost mothers, since men could make do, but women had a difficult time supporting children on their own. The development of philanthropic organizations for poor Jewish women indicated the extent of the problem, and asylums in a number of cities pointed to the feminine nature of poverty. Port cities like New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and New Orleans had the highest rates of Jewish female poverty, although inland and secondary communities had them as well. Almost every Jewish community special charitable event and organization turned their attention to alleviating the special suffering of Jewish women.

The specific problems of the Jewish female poor pointed to another aspect of Jewish women’s lives in America in the mid-nineteenth century: the creation of philanthropic and communal organizations by women, usually, although not exclusively, for women. The creation of these organizations, which in many communities called themselves Ladies’ Hebrew Benevolent Associations, actually represented the fairly simple transplantation to America of traditional Jewish women’s organizations from Europe, the hevrot nashim.

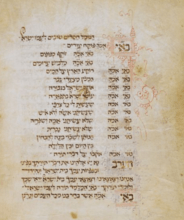

Ritually, the women had responsibility for performing the responsibilities associated with the burial of other women. The women in these associations, in Europe and in America, adhered to a tradition that required Jews to visit the sick (bikkur holim) and to prepare the dead for burial. Strict sex segregation had to be maintained: Men took care of the men; women ministered to the women. The women of the association purified the corpse, sat with it, read aloud from the Psalms, and accompanied the body to the cemetery. A women’s benevolent association of New Haven, Connecticut, in the 1850s was typical. Named Ahavas Achios [the love of sisters], it operated according to a formal constitution, which mandated a “sick committee” to sit at the bedside of the dying.

Between death and burial, two women remained with the deceased at all times. A specially trained group of ten women washed the body, and all members had to contribute six cents toward the “death cloth”—sewed by the women themselves—of any impoverished sister. Dues collected also went to various charitable purposes, determined by the members. By and large, funds amassed by the women supported the relief of female poverty and distress. Additionally, the women sponsored various fund-raising events, many of them quite American in format, like “dime parties,” theatricals, and “strawberry socials.”

These hevrot nashim functioned as complementary associations to the male hevra kadisha. They served the same religious and communal needs, and members and leaders tended to come from the same families. For example, Sarah Zlottwitz of Swerenz in Posen and Jacob Rich, who had migrated from the same town, married in 1853 at San Francisco’s Sherith Israel Congregation. At the time that they married, she served as treasurer of the Ladies’ United Hebrew Benevolent Society and he as secretary of the First Hebrew Benevolent Society, the men’s association.

In two ways, however, the women’s societies differed from the men’s, and these differences provide some important insights into the status and vision of Jewish women in the period of the German immigration. First, unlike the male associations, women’s groups did not hold title to the cemetery. Since these organizations were structured around issues of death and burial, this amounted to an important difference. Thus, some of the women’s associations installed men as their chief officers, and the men, who did own the cemetery, represented the women to the outside society. Secondly, the men’s associations tended to break down along congregational lines, according to place of origin in Europe, and even sometimes by occupation or neighborhood in an American city. Women tended to form more inclusive organizations, ones that served a broader swathe of the Jewish female population and which transcended the divisions that split the men.

The women may have opted for the more general type of organization because they did not belong to the congregations, which represented the most crucial and common division for the men. As women who had been excluded from discussions and debates about citizenship and emancipation in Europe, they may not have been especially identified with place of origin in Europe. Or it may be that because many of the Jewish communities in America had experienced periods of time in which women constituted a minority, the women gravitated toward each other, ignoring all sorts of other divisions, in search of female companionship.

Scattered evidence from many individual communities indicates that the women’s benevolent organizations did quite well at fund-raising and amassed solid treasuries. Although women did not belong to congregations, their benevolent associations often provided funding for congregations that wanted to rent space, as opposed to worshipping in homes and stores, or that wanted to move out of rented rooms into their own building.

Rabbi Liebman Adler of Detroit’s Temple Beth El lavishly praised the women of Ahavas Achios on the pages of Die Deborah, a German-language supplement to Isaac Mayer Wise’s Israelite. He noted that in 1859 these women had donated $250 “with the proviso that steps will be taken speedily towards the earnest realization of the long-discussed building of the synagogue.” In Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in 1874, the Ladies’ Hebrew Association had been asked by the men of the congregation for money. The women agreed to give, but only if “the Gentlemen’s congregation ... not use the money collected for rent of lot Cor[ner] North and Church ... and that the said money only be used for purposes of the Building Fund.”

These Jewish women’s associations, and others not necessarily connected to burial, maintained a strong presence in providing charitable relief to the Jewish poor. The widespread involvement of Jewish women in charitable work in America may have been a characteristic way in which Jewish women in America differed from their European counterparts. American Jewish women in this period, immigrants from various parts of Central Europe, created a wide range of charitable enterprises, and funded and operated them as well.

In America, Jewish women in various communities created orphanages, day nurseries, maternity hospitals, soup kitchens, shelters for widows, and the like. Groups such as the Montefiore Lodge Ladies’ Hebrew Benevolent Association in Providence, Rhode Island, engaged in friendly visiting to the needy and distressed, and gave out coal, clothing, food, eyeglasses, and medicine. The Johanna Lodge in Chicago helped newly arrived single immigrant girls set up businesses. Some of these organizations, such as the Deborah Society in Hartford, Connecticut, grew out of female burial societies. Others, such as the Detroit Ladies’ Society for the Support of Hebrew Widows and Orphans, started specifically as female philanthropic organizations. Some of the women’s charitable societies at some point had male boards of directors or a male president of the board; others operated with female-only leadership.

The organizational activities of Jewish women in America may have been inspired by the activities of charitable activism of Protestant women in their communities. Or it may have been in part modeled on the activities of the upper-class Jewish women and others from the Descendants of the Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal before the explusion of 1492; primarily Jews of N. Africa, Italy, the Middle East and the Balkans.Sephardic congregations like Ritual bathMikveh Israel, epitomized by Rebecca Gratz of Philadelphia, who pioneered in the creation of Jewish women’s organizations. The origins of the wide range of associational activities of Jewish immigrant women in mid-nineteenth-century America may actually have grown out of the migration experience itself. Young women and men came to America and had to create communities from the ground up. Without the support of parents and other family members, they were forced to create new kinds of institutions to deal with the problems engendered by their move.

Most of Jewish women’s associational life existed on the local level. Yet at least one attempt was made by some of them to create a nationally based organization in this period. The Unabhaengiger Treue Schwestern, the United Order of True Sisters, was founded in 1846 in New York, and by 1851 branches had spread to Philadelphia, Albany, and New Haven. Its lodges provided various forms of self-help to members, and like the men who at the same time in American Jewish history founded the B’nai B’rith, Kesher shel Barzel, and other fraternal orders, the True Sisters embellished its meetings with secret rituals, distinctive ceremonial garb, and other kinds of specific paraphernalia. Similar to B’nai B’rith, the True Sisters in some places operated as a kind of female counterpart or, indeed, as a ladies’ auxiliary to the larger all-male B’nai B’rith.

Religious Observance

The period of the German Jewish immigration also changed women’s relationship to Judaism as a religious system. Traditionally much of Jewish women’s crucial involvement in the maintenance of The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhah, the vast body of Jewish law and practice, took place in the home, as women performed their domestic chores. Those tasks had either direct or indirect connection to the fulfillment of ritual obligation, be it in preparing for the Sabbath, guarding the The Jewish dietary laws delineating the permissible types of food and methods of their preparation.kashrut of the family’s food, or monitoring the strict observance of laws of family purity. With a few limited exceptions, such as the hevrot nashim and the supervision of the ritual bath, used primarily by women to purify themselves before marriage, after childbirth, and upon the completion of their monthly menstruation, public Judaism in Europe functioned as an all-male preserve.

Migration to America challenged the dichotomization of Judaism into a public and private sphere, which roughly corresponded to the male and female. The migration made the observance of private Jewish ritual life, which is most closely tied to women’s activities, more difficult and less often observed. Communities struggled with the problem of securing Term used for ritually untainted food according to the laws of Kashrut (Jewish dietary laws).kosher food, and even in communities where kosher meat was available, high levels of community conflict ensued over the punctiliousness of slaughterers and butchers. Evidence points to a steady decline in the observance of kashrut in America. The shopkeepers and petty merchants who made up the vast majority of American Jews did not adhere strictly to restrictions of Sabbath activities either.

Instead, under the pressures of the American marketplace, where, for example, stores were usually closed on Sundays, they worked on the halakhically mandated day of rest. It is harder to know how many communities maintained mikves, the ritual baths, and how many women used them on a regular basis. Minutes of various congregational meetings in the mid-nineteenth century across the United States referred to the construction and maintenance of a ritual bath or to some controversy over its supervision. While the traditionalists among the immigrants of this period denounced Jewish women in America for their failure to fulfill the commandment of Menstruation; the menstruant woman; ritual status of the menstruant woman.niddah, communities did indeed build, according to sacred specifications, these facilities. There is, however, no reason to believe that this ritual proved to be any hardier than the others, and it too probably fell into disuse.

But, over the course of the period 1820 to 1880, Jewish women came to assume a more public presence in the observance of Judaism. This assumption did not come as part of any kind of challenge to the reality that membership in congregations and participation in congregational affairs continued to be limited to men. Women had to be expressly invited to attend congregational events, and no evidence exists that Jewish women sought to overtly challenge this status quo.

But American Jewish women began attending synagogue on a regular basis much more often than they would have had they remained in Europe, and indeed many commentators decried the fact that women worshippers often outnumbered men on any given Sabbath morning. Although they continued to sit in the women’s section, mothers often were the ones who brought their children to the synagogue, while husbands may have been standing behind the counters of the family store.

The preponderance of women present at synagogue was confirmed by many of the rabbis of the time, who viewed the move toward a feminized congregation as a problem. Isaac Mayer Wise, for example, who was a major advocate of mixed male-female seating, criticized this tendency in American Judaism. In 1877, for example, he reported in the Israelite, the newspaper he edited, about a recent trip to the West Coast. “All over California,” he lamented, “as a general thing the ladies must maintain Judaism. They are three-fourths of the congregations in the temple every Sabbath and send their children to the Sabbath schools. With a very few exceptions, the men keep no Sabbath.”

Jewish women did not seek to participate more fully in the affairs of the synagogues in this era. But the fact that in the years of the German Jewish immigration Jewish women came to predominate as worshippers may have laid the groundwork for a challenge that did take place in future decades. It may also be that the emerging female majority at Sabbath services influenced leaders of the Reform Movement like Isaac Mayer Wise, David Einhorn, and others to begin to call for mixed seating. They may have hoped that moving toward family pews, as opposed to retention of sex-segregated service, would bring the men back to services.

Additionally, rabbis, particularly the Reform-oriented, were aware of a public discourse in Christian magazines and among gentile Americans about the supposed backwardness of Judaism, exemplified by the segregation of women during religious services. Some Americans wrote about this practice as an “oriental” atavism, a “mistreatment” of women, and a “great error of the Jews,” in which “she is separated and huddled into a gallery like beautiful crockery ware, while the men perform the ceremonies below.” Indeed, Christian writers at this time of militant evangelicalism held up the separation of Jewish women in the synagogue as evidence of the rightness of Christianity. “It was the author of Christianity,” noted one writer, “that brought her [the woman] out of this Egyptian bondage and put her on an equality with the other sex in civil and religious rites.”

Print Journalism

Whatever the motivation of the leaders of Reform, Jewish women in the middle decades of the nineteenth century began to make themselves more publicly visible as Jews and as the defenders of Judaism. Jewish women, for example, began to produce religiously inspired literature in almost all of the Jewish publications, including Die Deborah and the Israelite, which represented the Reform-oriented tendency in American Judaism, and The Occident and Jewish Messenger, which stood on the more traditional end of the spectrum.

Their poems, short stories, and nonfiction emphasized the importance of loyalty to Judaism and to family. They depicted women as the bearers of the Jewish tradition through their families, and they encouraged young Jews, both women and men, to steadfastly resist assimilation into Protestant American culture and to withstand the aggressive efforts of evangelical Christian organizations.

The entrance of Jewish women into the world of print journalism represented a significant departure for them. They had no models for women engaging in this kind of activity. Indeed, one woman writing as “Miriam” for the Jewish Messenger begged her readers’ pardon, for “it may appear presumptuous in a female to enter into comments upon scriptural themes, but the daughters of Israel have always felt that allegiance to Zion was paramount to every other sentiment.”

By their behavior, Jewish women in America in the period 1820 to 1880 shared much with other American women. Both Jewish and Christian women responded to the same social and cultural contexts of industrializing America, in which men came increasingly to define their worth and identity in terms of the acquisition of wealth and less in the realm of the sacred. As men moved away from a commitment to community through religion, women filled the vacuum.

Conclusion

American women in general participated actively in nineteenth-century public religious life in a way that overtly jarred with traditional European Jewish practice. The “cult of true womanhood” of mid-nineteenth-century America assigned to women the proper zone of morality and goodness and defined religion increasingly as falling under women’s sphere of influence. As religion faded in significance to men in Victorian America, women, powerless in the political arena, turned to religion as an institution in which over time they could function comfortably. Jewish women’s behavior followed along these lines, although they did not directly challenge the policies and procedures of synagogue life.

The era of the German Jewish immigration brought approximately 150,000 Jews to the United States from Central and Eastern Europe. Women accounted for half of the immigrants, and they played a key role in the functioning of a family economy that allowed for steady and modest economic mobility, for the formation of communities from the ground up, which in turn provided services for the needy and for the emergence of a modern, American Judaism.

Barkai, Avraham. Branching Out: German-Jewish Immigration to the United States, 1820-1914. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1994.

Cohen, Naomi. Encounter with Emancipation: The German Jews in the United States, 1830–1914 (1984).

Diner, Hasia R. A Time for Gathering: The Second Migration, 1820–1880 (1992).

Kohler, Max J. "The German-Jewish Migration to America." Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society 9 (1901): 87-105.

Strauss, Herbert A. “The Immigration and Acculturation of the German Jew in the United States of America.” In Year Book XVI of the Leo Baeck Institute (1971).