Turkey: Ottoman and Post Ottoman

Jewish people in Turkey participated in and were affected by the enormous political, social, and geopolitical changes that occurred in the Ottoman Empire in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Jewish women in Turkey engaged in numerous customs of Judeo-Iberian and Turkish origin that shaped their approach to marriage, housekeeping, child-rearing, participation in religious life, and language. Although these women traditionally remained in the private sphere of the home, socializing primarily with other women and prioritizing domestic responsibilities, during this period they began to access education and participate in politics as well, largely in the context of the “Young Turks” rebellion. While many Turkish Jews came to participate in Turkish politics, Zionist groups flourished in the community as well.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, far-reaching changes took place in the Ottoman Empire in the political, social, and geopolitical spheres. From the late nineteenth century until 1923, Turkey was frequently at war. The Treaty of Lausanne (1923) established the borders of the Turkish nation-state, with a population that was ninety-six percent Muslim. In the wake of the Tanzimat reforms, the “Young Turks” rebellion (1908), geopolitical shifts, and the establishment of the Republic, the Turkish state imposed a process of “Turkification” on its residents.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Jews of Turkey constituted the largest Jewish community in the Ottoman Empire, centered primarily around Istanbul and Izmir. After 1923 the Jews gathered in these cities, effectively eliminating the smaller communities in Western Anatolia and Romelia. Concurrently, a massive migration to Europe and the Americas took place. In the 1930s, out of a total Turkish population of fifteen million, 150,000–200,000 were Jews. Between 1927 and 1938 the number of Jews plummeted to 70,000. At the end of the twentieth century, the Jewish community of Turkey numbered about 20,000 people.

The Women’s Domain

One of the central features in the lives of Jewish, Christian, and Muslim women was the separation between men and women. This separation had an impact on numerous aspects of everyday life, among them the division of labor between the genders, the restriction of women to the home, and the exterior architecture and interior design of the living space. The consignment of the Jewish woman to the home derives not only from the Jewish tradition, which holds that “all the honor of the king’s daughter is within” (Psalms 45:14), but also from the dual influence of Muslim society and Descendants of the Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal before the explusion of 1492; primarily Jews of N. Africa, Italy, the Middle East and the Balkans.Sephardic custom.

The public space, which included the streets, the marketplaces, the port and its piers, the coffee houses, and the synagogue, was considered the masculine domain. The private space, associated with the women, was limited to the home, the courtyard, the communal oven, the well, the Ritual bathmikveh (ritual bath), and the women’s section and courtyard of the synagogue. Neither married nor single women ventured out into the street alone; they emerged only in groups, with a defined destination for their visits (vijitas)—either other homes or the mikveh. Separation was also the rule with respect to burial and shiva (the one-week mourning period); women did not attend funerals, instead visiting the cemetery in groups, primarily on [jwa_encyclopedia_glossary:389]Rosh Hodesh[/jwa_encyclopedia_glossary] (the festival of the new month).

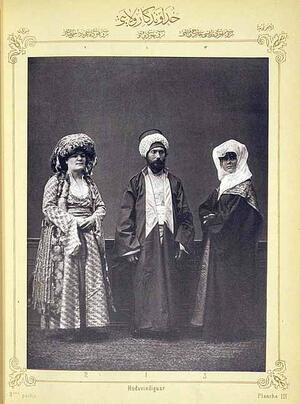

Since the entry of women into the public space placed their modesty at risk, a woman’s attire served as a protective barrier outside the home while at the same time defining her nationality and her social and economic status. Rich and poor women alike wore the same clothing, but there was a difference in the quality of the workmanship, the richness of the fabric, and the accompanying jewelry. The presence or absence of the latter testified to the woman’s marital status. Jewish women, like their Muslim and Christian sisters, went out into the street wrapped from head to toe in a cloak of sorts (ferace) topped with a veil (marama). As a result of European influences in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Western clothing “infiltrated” all levels of society, although few Muslim women abandoned the veil.

Language represented an additional barrier that relegated women to the private space and prevented them from playing a role in the public domain. Until the mid–1950s, Judeo-Spanish (Djidio, in Ladino) was the primary spoken language of the Jews. While most of the men knew how to speak Turkish, chiefly as a result of work and business connections, and some Hebrew, acquired as part of their religious studies, the language of women’s discourse was Ladino. Lack of knowledge of the official languages did not hinder the women’s communication with others, however, since all of their neighbors (including the non-Jews) spoke and understood Ladino. The Jews lived together in neighborhoods where they constituted the majority. Their homes, which opened onto shared courtyards, were simple dwellings referred to by the locals as yahudihane (in Turkish) and by the Jews as cortijo, or “cottage.” The entrance to the courtyard was guarded by a heavy wooden door reinforced with iron bands and locked with a vertical iron bolt. An opening between the courtyards allowed the women to move from one enclosure to another without exiting into the street.

The interior of the home was the woman’s domain, as reflected in the custom of providing a dowry (ashugar, in Ladino) to the woman upon her marriage. The bride brought with her the furnishings and interior fixtures of the bed chamber (cama armada), the household and kitchen utensils, curtains and tablecloths, in addition to clothing, jewels, and money. The custom of dowry indicates that the woman and her family expected her to have a home in which to place these objects.

Women’s Sense of Time

The majority of the women were illiterate. Since they could not read newspapers and were not taught to read the yearly calendar that formed the basis of Jewish life, the women had their own unique sense of time and place. The opening of special schools for girls, compulsory education instituted by the Turkish authorities, and the penetration of radio, gramophones, and films all influenced the women and brought the wider world to their doorstep. In other words, the women were aware of changes in time and space, but these did not lead to a synchronization between the broader world of Turkey and beyond, on the one hand, and their own sense of time, on the other. It was essentially the latter that continued to serve the needs of the family. From the way in which Jewish women allocated their time, it is apparent that they were preoccupied with household tasks. Their attention, their time, their feelings were devoted to the home and family, in particular to cooking and cleaning, the means through which the woman made her unique mark on her home. A clean home testified to the character of the housewife, who thereby earned the appreciation of the household, the family, and the neighbors. Cleaning and cooking took up most of her time, dictating her daily schedule and the dishes that she prepared. A special day was set aside for laundry. The tasks of running the household were numerous and the prevailing attitude was that girls did not need to study. What they required was guidance, warmth, and love, which their mothers bestowed in abundance. Consequently, young girls remained in the home to oversee the smaller children and to help clean house.

The Kitchen

Food was prepared and served in accordance with the season, the festivals, and the Jewish dietary laws. The names and flavors of the dishes were reminiscent of the community’s origins in Spain and Portugal (prior to the Expulsions of 1492 and 1497): pan de españa, tortas, fila-dona, frojaldai and kezada, to name a few. Foods that were prepared quickly and were not the product of hours of work were evidence of a lazy, gluttonous housewife. Special dishes were prepared for the Sabbath and holidays. In the period preceding A seven-day festival to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nissan. Also called the "Festival of Mazzot"; the "Festival of Spring"; Pesah.Passover, the women rarely left the home, due mainly to the work of housecleaning and preparing the special festive meals.

Food preparation and cooking were done individually. In contrast to laundry day, which was a social event, the peeling of vegetables and preparation of dough were carried out within the privacy of the home. Young girls learned how to cook in their own home, from their mother. A girl who did not know how to cook and was unschooled in the tasks of homemaking brought shame not only upon herself and her husband but on her mother and family and even harmed the marital prospects of her sisters, since the deeds of the daughter reflected on the mother, who had not succeeded in preparing her daughter to perform household chores. Women prepared the food but endeavored to avoid eating in public and ate slowly and in small portions. A woman who never complained, did not crave luxuries, was frugal and healthy, and did laundry earned the title nikuchira, meaning a good housewife who runs her home properly.

Through her delicacies and baked goods, in which she invested hours of toil and devotion, the wife and mother was able to create a sense of uniqueness. Women sent homemade foods to newlywed couples during the seven days of post-wedding festivities, or, by contrast, to relatives and friends whose family member had passed away. Women did not take part in political activity in the community but did participate in communal life through the distribution of food. Affluent women provided food to soup kitchens, while poorer women donated breast milk to orphaned infants whose mothers had died in childbirth or had insufficient milk. They shared their meager bread with people poorer than themselves, with the birds, the dogs, and the street cats, as part of the network of charity and compassion that characterized women.

Healing Women

Virtually every ailment was attributed to “the evil eye” or to fear. Until the late nineteenth–early twentieth century, the custom of indulco (ritual confinement) was widespread throughout the Ottoman Empire. The treatment ritual was carried out by a woman with special healing powers who was known for her ability to exorcise demons, generally those that had entered a woman. Women who were trained in this practice were sought out due to a shortage of doctors, lack of money, concerns of modesty and the belief that the ancient treatment was effective. An examination of the substances used by the healer in the ritual shows that these were foodstuffs commonly found in any Sephardic Jewish woman’s kitchen throughout the Mediterranean Basin: water, rose water, honey, salt, and eggs. In the early twentieth century, this custom faded into obscurity, largely due to the ban imposed by the rabbis, the establishment of hospitals, and the system of public health care. Jewish women played a role in this communal health network through women’s societies that collected donations for hospitals, in addition to serving as nurses, attendants and auxiliary personnel.

Marriage

Until the late nineteenth century it was customary in Turkey to marry at an early age, with the grooms generally being seventeen to eighteen years old and the brides fourteen to fifteen. The reasons for marrying young included the high mortality rate and short life expectancy (parents wished to see their children settled, meaning that they had produced offspring and the family line had not been extinguished); the fear that the girl would be seduced and bring shame upon her family; and the fear of conversion and intermarriage to a Muslim or Christian. However, the practice of marrying girls off at a young age sometimes led to tragic results. The first year of marriage carried the highest incidence of mortality for women and newborns since the young girls had not yet reached physical and sexual maturity due to malnutrition, poor hygiene, and family pressure to produce offspring early in the marriage.

There was generally a set hierarchy within the family: the oldest daughter married first, followed by the remaining sisters in descending order of age. An important prerequisite for marriageability, apart from obedience, modesty, a good reputation, and virginity, was the dowry (dota y ashugar, in Ladino). Without a dowry, there was no marriage. Haim Nahoum, the chief rabbi of Turkey from 1892 to 1923, requested a loan to marry off his sister (“one of my sisters, who became engaged two years ago, is forced to postpone her wedding until the Messiah comes [i.e., indefinitely] for want of 1,000 francs, which she promised to provide in legal tender to her betrothed”).

In addition to currency, the bride brought to the marriage her own apparel and the furnishings for the bedchamber. In the twentieth century new items made their way into the traditional dowry: girls who had studied at one of the foreign schools or at the school of the Alliance Israélite Universelle added books in French and Italian as well as training in bookkeeping, administration, and a musical instrument. An additional article was the sewing machine, which was not only a symbol of modesty and of being tied to the home but also a manufacturing tool: the woman could now work at home, as a subcontractor to sewing workshops. The preoccupation with the dowry as an integral part of marriage was a cause for concern among the community leaders; in order to reduce the social pressure and the moral problems liable to be caused by the surplus of single young women, the community set up a “dowry fund” aimed at providing dowries to orphaned and impoverished young girls. Money for the fund came from inheritance taxes, levies imposed on dowries and generous donations.

Most of the matches took place within the family (to cousins or other relatives) and were determined by the parents. Wealthy families, such as the Camondos or the Agimans, married within the family or with other wealthy, high-born urban families.

The modern education in the Alliance schools and the inclusion of the girls in youth movements and communal activities expanded the selection available to young men and women and narrowed the age gap between couples. Despite the element of personal choice, however, and largely because this was a class-based society, the encounters were not spontaneous and the choice of spouse did not extend beyond one’s own social group.

Wedding festivities, which in the past had lasted for two weeks, were now shortened, mainly for economic reasons. In the nineteenth century wedding ceremonies and festivities took place separately for men and women, but in the twentieth century these celebrations became mixed.

The wedding ceremony comprised several elements. The personal and feminine component was represented by the bride. Though the bride was not an active participant at any stage of the wedding—she was chosen, dressed, led, and “acquired” with a wedding ring or other valuable— the wedding ceremony was nevertheless the most significant event of her life and the culmination of a process toward which she had been guided since childhood, that of becoming a wife and mother. The groom’s obligations toward his bride were anchored in the Marriage document (in Aramaic) dictating husband's personal and financial obligations to his wife.ketubbah (marriage contract), which served as a legal document protecting the rights and property of the woman.

The one portion of the wedding festivities in which women alone took part was the day of the bride’s immersion in the ritual bath (el dia del banio, in Ladino). Each part of the ceremony had a special significance. The pristine waters of the spring symbolized the purity of the bride. Pieces of sugar were added to the water to ensure a sweet life. The immersion was not an intimate event but a ceremony attended by all the women of the family. The bride was perfumed with rose water and each of those present helped to dress her. The ceremony was accompanied by traditional songs praising the bride’s beauty, innocence, modesty, and her future as a married woman. In Izmir it was customary to break a cake-ring (kezada) over the head of the bride.

The bride’s procession from her home to that of the groom was not a private event of two families joining together in marriage. The entire assemblage of family members and guests took part in the rejoicing, accompanying the bride with music and song. The ceremonial escorting of the bride to the home of the groom was similar to the festivities surrounding the dedication of a new Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah scroll for the synagogue and the wedding songs were mixed with hymns praising God’s Torah and the Land of Israel, climaxing with the breaking of the goblet by the groom in remembrance of the Temple’s destruction. The custom of publicly escorting the bride began to die out early in the twentieth century, primarily due to the processes of Westernization and “Turkification” under the Republic.

After the wedding the newly married couple moved into the house of the groom’s parents. Living together with the mother of the groom was at times problematic. The bride brought with her opinions, ideas, and habits learned in her own mother’s home that did not always conform to the practices in the home of her mother-in-law. The bride and her mother-in-law vied for the use of the oven and the sink, not to mention the approval of the son/husband. Often, the bride, the mother-in-law, and the sisters-in-law (the sisters of the groom, or other daughters-in-law living under the same roof) had trouble getting along, turning life in the home into a series of quarrels and squabbles that sometimes required the groom to take a stand and even led to divorce.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the changes in the traditional marriage customs were compounded by other factors: migration, conscription, wars in the Ottoman Empire, and the Family and Matrimonial Law enacted in 1925. The new law, inspired by similar legislation in Switzerland, made civil marriage mandatory, although a religious ceremony was still permitted.

The period of the woman’s pregnancy was a time of rejoicing mixed with fear. During the fifth month of pregnancy, a diaper-preparation ceremony (cortar fashdura) took place, attended by the women of the family and female friends and neighbors. The birth of a daughter, unlike that of a son, was met with disappointment, principally due to the burden of providing a dowry.

When a daughter was born, a fadamiento or siete candelas ceremony was held (corresponding to the circumcision ceremony), at which the baby girl was given a name. The ceremony was usually held in the home or at the synagogue, with the infant dressed in clothing embroidered with gold and silver. Each of those present lit a candle and blessed the newborn girl with a life of joy and prosperity.

The names of the women bear witness to the changes in time and space, as well as the cultural and social transformations, which took place over the course of generations. Until the late nineteenth century, women were as a rule given ancient Hebrew names such as Sarah, Esther, or Rachel, or names originating from the Iberian Peninsula, including Oro (gold, in Ladino), Estreya (star), Alegre (happiness), Amada (beloved), Bolisa (housewife), Joya (jewel), Vida (life), Luna (moon), Sol (sun), and Regina (queen). It is no coincidence that girls were given names that expressed beauty and sweetness; these names conformed to the expectations of beauty and modesty that were placed on women. All of the names reflected the longing for, and promise of, a good life, but names such as Merkada (acquired, in Ladino), Haya (life), and Bohora (firstborn) carried an additional meaning. Merkado/Merkada was not a name bestowed on a child at birth but instead was given to a man or woman in danger of dying. To confound the Angel of Death, the person was symbolically “sold” to a family member. Other names that were particularly popular were Dudun and Hanum. The name Dudun was given when the baby’s mother and paternal grandmother had the same names. Hanum is a corruption of the Turkish word hanim, meaning lady or mistress. Over the centuries the Jews assimilated into the surrounding community and took on local names, but these still differed from the first names customary among the Muslims. One example is the name Sultana, which corresponds to the Hebrew name Malka (queen) and to Reina and Regina in the Spanish; despite its Turkish origins, Muslim women did not use this name. With the infusion of the French language and culture in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, new names were added: Mazalto(v) became Fortune, Gracia became Germaine, and Regina became Regine, to mention a few. In the 1950s, the desire to become part of Turkish society also had an impact on patterns of baby-naming and girls were given Turkish names.

Honor

The spectrum of values reflected in the concept of “honor,” in the sense of generosity, honesty, seriousness, loyalty to friends and family, and defense of the weak (i.e., women and children), relates to men. The honor of women, by contrast, is expressed through their modesty, particularly in the sexual realm. The woman was expected to sublimate her sexuality, the appropriate means of entry to the community at large lying in the number of offspring—preferably male—that she brought into the world. Women learned to keep silent and to accept their fate. A unique form of expression for women was poetry, through which they gave voice to their emotional state, to their hopes and dreams. The ancient romansas (narrative ballads) originating in the Iberian Peninsula express the problem of cultural identity, or more precisely, cultural alienation from the immediate time and place, in this case the Turkish state. Concurrent with the romansas, and inspired by Turkish folk poetry, a new poetry emerged that drew on the surrounding reality and expressed the women’s social status, their hopes and aspirations.

Education and Schooling

One way for women to be integrated into the communal space was via education. Since few Jewish schools existed, Jewish girls studied at schools under the auspices of the Christian mission. Fees at these private schools were high and the prevailing attitude among the men, and even more so, the mothers, was that young girls did not need to be “smart”; as a result, most of the girls were not sent to school. Young girls from affluent families studied in private schools under the patronage of the convents or with private tutors.

In the late nineteenth century, the Alliance Israélite established schools for boys and girls, with the aim of revitalizing Ottoman Jewry through education and changing the status of Jewish women in the Sephardic communities. The girls’ curriculum differed from that of the boys; in addition to French, general studies, and Turkish (in Izmir, they studied Greek), the girls learned sewing and embroidery. In 1872 the Alliance decided to include women among the teaching personnel. By 1929 seventy-nine young Jewish women from Turkey had completed teachers’ college in Paris. This low figure suggests that, despite the social prestige of the profession, most families preferred the time-honored practice of marrying off their daughters.

Young girls of fourteen who excelled in their studies were sent to study at the teachers’ college in Paris, after which they taught or served as principals at girls’ schools in Tunis, Morocco, Istanbul, Haifa, and elsewhere. From the reports of women principals of Alliance schools to the central office in Paris, the portrait emerges of a vigorous, independent new Sephardic Jewish woman who emerged from the Alliance schools. They considered themselves a part of both general Ottoman society and the Jewish community; yet, as representatives of the Alliance, they sometimes found themselves in conflict with the Jewish community and its leadership, who were fearful of changes in the standing of Jewish women. During the Balkan wars and World War I the women operated workshops in the schools that produced sheets and bandages for hospitals in the large cities of Edirne and Istanbul and ran a fundraising and assistance network within the Jewish and local communities.

Turkish Jewry was not unaffected by the changing times. The subject of education for women came up at conferences conducted by the Jewish community, with the general attitude being that women were equal to men and had the same right to an education; since they had different functions to fulfill, however, their education must be suited to their future role, that of being a mother. With the establishment of the Republic, sweeping changes were instituted in Turkey’s national educational system and many teachers lost their jobs.

Leisure Time

Women as a whole made similar use of leisure time, although there were differences between the classes. The more affluent women met in the homes of female relatives or friends. At these gatherings, they caught up on the local gossip and mothers of young men surveyed the “pool of potential brides” who came with their mothers, checking their manners and personal traits and analyzing the economic status of the well-known families and the marriage market in general. Women and young girls knitted, embroidered, and exchanged recipes. On occasion, a table would be set out, and a few of the women would launch a friendly game of cards for small sums of money, some of which was donated for charitable purposes. Women’s organizations were established whose primary goals were the organizing of donations for destitute orphans, fundraising for the dowries of poor girls, and volunteering in charitable institutions of the community, such as orphanages, hospitals, and soup kitchens.

Dozens of Jewish newspapers were published in Istanbul and Izmir, but there were initially none geared specifically to women (even the humor sections appearing under women’s names, such as Kadonika and others, were not necessarily written by women). In 1895, a Turkish-language magazine for women appeared for the first time in Istanbul.

The Ladino literature and folk ballads that flourished in the late nineteenth century offer evidence of a new factor that had entered the lives of Jewish women in Turkey: love. Owing to the power and influence of the family, this concept was rarely acted upon, and young girls who “strayed” in the name of love paid for it with their honor and sometimes with their lives. One form of leisure-time activity that captivated all of Turkish Jewish society, men and women alike, was the cinema. Women went out to movie theaters, accompanied by female relatives, friends, and neighbors. Another popular form of entertainment was festive balls organized by the Jewish community, largely to raise funds for Jewish charitable institutions and for the Turkish army.

Political Sphere

The silence of women both inside and outside the home was reflected in the realm of communal activity. Women did not take part in political and social decision-making, nor did they participate in elections to the community council. While Turkish women ventured out of the home to study in state schools for training teachers and midwives, and from 1908 onwards were permitted to study at university, Jewish women did not study in these schools, principally because they did not speak Turkish. Although a number of Jewish men participated in the political changes taking place in Turkey, including the Young Turks rebellion, and Jews were elected to the Turkish parliament, the women’s voice was not heard.

The revolt of the Young Turks had an impact on the perception of the Turkish woman and the notion began to spread that women should be politically aware in order to educate their children. In other words, a new aspect was added to motherhood, that of nationalism. The entire family was enlisted in the Zionist cause, with politically aware Jewish girls and women recruited to assist the Jewish national movement, which operated openly from 1908 to 1910. Parents sent their daughters to the Girls’ Section of the Maccabi Gymnastics Club, to movement hikes and to other activities, but after political and national gatherings were banned, Jewish men and women alike vanished from the political arena. During World War I Jewish girls and women went out to work in factories, both to assist in the war effort and as a means of supporting themselves in the wake of the conscription of the men. Late in World War I, a group sponsored by the Joint Distribution Committee of American Funds for the Relief of Jewish War Sufferers (later known as the JDC, or the Joint), in conjunction with B’nai B’rith, distributed 6000 food parcels daily to Jewish women whose husbands were missing in action, war orphans (1,500 in number), refugees, and other needy Jews.

As a result of the ban on activities of political organizations not affiliated with the state, there is virtually no information on public activities of the women’s Zionist organizations, although there is evidence, chiefly from oral testimonies, that young girls took part, together with young men, in clandestine Zionist groups. Despite the fact that women did not participate in politics, Jewish women served as the pretext for a slur campaign maligning the patriotism of Turkish Jewry. In addition to the claim that the Jews ate different food and spoke a different language, and that their loyalty to the Turkish state was suspect, the question was raised of why Jewish women did not marry Muslims. The campaign reached its climax with the Aliza Niego affair, in which a young Jewish girl was murdered by a married Muslim suitor, his father, and his grandfather while walking along an Istanbul street with her sister. The mass funeral that followed offered a ready excuse for nationalist elements to attack the Jews, claiming that the gathering was a demonstration against the Turkish Republic and a disturbance of the peace. The prosecutor in the case later referred to Aliza Niego as a “daughter of Zion,” noting that the Jews bore the coffin of the deceased as if she symbolized Turkish Jewry in its entirety.

In 1934 men and women above the age of twenty-two were granted the right to vote in parliamentary elections and to stand as candidates. Jewish women entered the political scene at a slower pace than their Turkish counterparts, not because of a lack of skills but because all the minorities—among them, Jews in general and Jewish women in particular—were not (and did not always wish to be) integrated into the Turkish national space. Those young Jewish girls who were politically aware—largely as a result of antisemitism and the masses of refugees who streamed from occupied Europe during World War II—secretly dreamed of The Land of IsraelErez Israel, some even taking part in clandestine activities of the Ne’emanei Zion and He-Halutz associations operating in Izmir and Istanbul and the Betar movement in Edirne. The young girls who participated in the activities of the Zionist movement did not breach the accepted frameworks but acted with the blessing and approval of their families. “Young girls scarcely take part in the prohibited activities of the He-Halutz movement, and this is because, despite all the rights granted them under the law, they cannot walk around by themselves at night. And this does not stem solely from the conservatism of the parents; rather, there is a genuine danger, because they could be snatched from a street corner and the matter could end in tragedy. Turkish women in general are not seen on the streets. One sees only Jewish and Greek women” (Central Zionist Archives, S25/6308, June 29, 1946).

Strict separation was maintained between girls and boys in all the groups. Young women served as group leaders for the girls and were involved in community life, tutoring pupils, helping at orphanages, teaching Hebrew, putting on plays, and founding a choir. During World War II they assisted Jewish refugees from Europe who had fled to Turkey and took part in the smuggling of Jews to Palestine. The liaison with the “border crossers” in the eastern city of Gaziantep was a woman known as the Night Seamstress. World War II, in particular the activities of the Rescue Committee and the Zionist emissaries from Palestine based in Constantinople, led to a certain shift in the political attitudes of both the young girls and their parents, which expressed itself in the immigration of young people to Palestine. Young girls who in Turkey had not ventured out of their doors for fear of harassment were sent to A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutzim in Palestine at the age of fourteen or fifteen as part of Aliyyat ha-No’ar (Youth Lit. "ascent." A "calling up" to the Torah during its reading in the synagogue.Aliyah).

Emigration

For centuries, widows had immigrated to The Land of IsraelErez Israel to live out their final days there and be buried in its soil. They were supported by their sons who remained behind in the city of their birth and sent them a yearly stipend known as añada. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries a wave of emigration began, primarily to France and the Americas, due mainly to political instability, the economic crisis/the Depression, wars, and mandatory conscription of minorities.

This emigration also had a gender aspect. In the wake of the departure of the young men, many young women of marriageable age were left behind in Turkey, as portrayed in the folk song “Buenos Aires”: “As soon as it opened/it filled with boys./The first is my lover/He went and left me.”

Many young women understood that if they waited until their prospective grooms had saved enough money to marry off their unmarried sisters and bring over their parents and only then be free to marry them, they themselves would remain unmarried for a long time. Young girls immigrated to pre-state Palestine as part of Youth Lit. "ascent." A "calling up" to the Torah during its reading in the synagogue.Aliyah, while women whose husbands had emigrated to avoid conscription took the children and left Turkey in any way possible.

Turkey became a multi-party democracy between 1945 and 1948. Following the elections of 1946, the rights previously stripped from them were restored to the Jews. Beginning in 1947, Jewish institutions and organizations began to renew their activities: sports groups, B’nai B’rith, and camps for Jewish children were established.

In schools with a majority of Jewish children, Hebrew and religion were studied once more. With the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, Jews were forbidden to immigrate there, but when the government changed in 1949, a mass aliyah began. Within four years, over half of Turkey’s Jews reached Israel. At the end of the twentieth century, there were some 20,000 Jews living in Turkey, who were involved in all spheres of society, the economy, education, science, and culture. While the younger generation is no longer fluent in Ladino, the community has a Ladino theater group, a musical group, Ladino journal, and a museum. Jewish women poets and writers are publishing poetry, collections of sayings, stories, and cookbooks in Ladino and Turkish.

Primary Sources (Archives)

Central Zionist Archives, Jerusalem. S3/463/2, February 26, 1941.

S75/1504 1505, 1506, 1943–1944.

S25/6308, June 29, 1946.

Archives de l’Alliance Israélite Universelle. Dossiers: Turquie XCVI E, carton 7145. Turquie II B4–7, carton 657, 1–4.

English Secondary Sources (books and articles)

Benbassa, Esther. Hayim Nahoum, A Sephardic Chief Rabbi in Politics, 1892–1923: Selected Letters and Documents (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 1998 (English edition, Tuscaloosa, AL: 1995).

Duben, Alan, and Cem Behar. Istanbul Households: Marriage, Family and Fertility, 1880–1940. Cambridge: 1991.

Jelavich, Barbara. History of the Balkans: Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. 2 vol. Cambridge: 1983.

Karpat, Kemal H. Ottoman Population, 1830–1914: Demographic and Social Characteristics. Madison: 1985.

Lamdan, Ruth. A Separate People: Jewish Women in Palestine, Syria and Egypt in the Sixteenth Century. Leiden: 2000.

Levy, Avigdor. The Sephardim of the Ottoman Empire. Princeton: 1992.

Levy, Avigdor, ed. The Jews of the Ottoman Empire. Princeton: 1994.

Lewis, Bernard. The Emergence of Modern Turkey. 3rd edition. New York-Oxford: 2002.

McCarthy, Justin. Muslims and Minorities: The Population of Ottoman Anatolia and the End of the Empire. New York: 1983.

Rodrigue, Aron. French Jews, Turkish Jews: The Alliance Israélite Universelle and the Politics of Jewish Schooling in Turkey, 1860–1925. Bloomington, IN: 1990.

Hebrew, Ladino and French Secondary Sources (books and articles)

Attias, Moshe. Romancero Sefaradi: Romansas y cantes populares en Judeo-Español (Hebrew and Ladino). Jerusalem: 1961.

Attias, Moshe. Jewish-Sephardic Cancionero: Folk Songs in Judeo-Spanish (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 1972.

Bardavid, Beki. “The Life of Turkey’s Jews from 1850 to 1950” (Ladino). Aki Yerushalayim 61 (1999): 15–17.

Benbassa, Esther, and Aron Rodrigue. Jews of the Balkans: Judeo-Iberian Spaces, Fourteenth–Twentieth Centuries (French). Paris: 1993.

Bornstein-Makovetsky, Lea. “Activities of the American Mission” (Hebrew). In Yemei ha-Sahar: Peraqim be-Toledot ha-Yehudim ba-Imperiyah ha-Otmanit, edited by M. Rozen, 273–310. Tel Aviv: 1996.

Bornstein-Makovetsky, Lea. “Immigration to Erez Israel from the Ottoman Empire in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries” (Hebrew). Shorashim ba-Mizrah: Kevatzim le-Heker ha-Tenu’ah ha-Zionit ha-Halutzit be-Kehilot Sefarad ve-ha-Islam 5 (2002): 71–96.

Chikorel, Avraham, Araham Strumza, and Shelomo Rabi, eds. History of the Ne’emanei Tzion–He-Halutz Movement in Izmir, Turkey (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: 2002.

Falkon, Mordehay, Daniel Tzipper, and Mashih Avidan, eds. Zionism and the Jews of Turkey (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 2000.

Friling, Tuvia. “Between Friendly and Hostile Neutrality: Turkey and the Jews During World War II.” In The Last Ottoman Century and Beyond: The Jews in Turkey and the Balkans, 1808–1945, edited by Minna Rozen, vol. 2, 309–423 (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: 2002.

Galante, Avraham. History of the Jews of Turkey (French). 9 vol. Istanbul: 1985.

Gerber, Hayim, and Ya’akov Barnai. Jews of Izmir in the Nineteenth Century: Turkish Documents from the Shar’i Religious Court (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 1985.

Levi, Avner. “Attitude of the Turkish Authorities and Society towards the Jews in Connection with the Alizah Niego Affair” (Hebrew). In Hevrah ve-Kehilah, mi-Divrei ha-Kongres ha-Beinleumi ha-Sheni le-Heker Moreshet Yahadut Sefarad ve-ha-Mizrah, 1984, edited by A. Hayim, 237–246. Jerusalem: 1991.

Levi, Avner. History of the Jews in the Republic of Turkey: Their Political and Judicial Status (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 1992.

Nahum, Henri. “The Jews of Izmir in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries” (Hebrew). Shorashim ba-Mizrah: Kevatzim le-Heker ha-Tenu’ah ha-Zionit ha-Halutzit be-Kehilot Sefarad ve-ha-Islam 5 (2002): 122–151.

Rosanes, S. A. History of the Jews of Turkey and the Eastern Countries in Recent Generations (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 1945.

Rozen, Minna. “The Life Cycle and Significance of Old Age During the Ottoman Period” (Hebrew). In Daniel Carpi Jubilee Volume, edited by Dina Porat, Minna Rozen, and Anita Shapira, 109–175. Tel Aviv: 1996.

Rozen, Minna. “Public Space and Private Space Among the Jews of Istanbul in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries” (Hebrew). Turcica 30 (1998): 331–346.

Rozen, Minna, ed. Days of the Crescent: Chapters in the History of the Jews in the Ottoman Empire (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: 1996.

Rozen, Minna. The Last Ottoman Century and Beyond: The Jews in Turkey and the Balkans, 1808–1945 (Hebrew), vol. 2. Tel Aviv: 2002.

Rozen, Minna. The Last Ottoman Century and Beyond: The Jews in Turkey and the Balkans, 1808–1945 (Hebrew), vol. 1 (forthcoming).

Shaul, Eli. Folklore of the Jews of Turkey (Ladino). Istanbul: 1994.

Yohas, Esther, ed. Sephardic Jews in the Ottoman Empire: Aspects of Material Culture (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 1989.

Idem. “Characteristic Jewish Attire.” In Yehudei Sefarad ba-Imperiyah ha-Otmanit: Perakim be-Tarbut ha-Homrit, edited by Esther Yohas, 120–171 (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 1989.