Canada: From Outlaw to Supreme Court Justice, 1738-2005

Article

At the beginning of Jewish history in Canada, there was a woman. In 1738, Jacques LaFarge, a recently arrived sailor in Quebec City, was arrested for suspicious behavior. In that small, close-knit colonial outpost, it probably did not take much to arouse suspicion, but, as it turned out, there was good reason to question LaFarge. To be sure, the sailor posed no security threat; his presence, however, was proscribed by law. The sailor was, in fact, not a man but a woman. “His” name was not Jacques LaFarge but Esther Brandeau. And she was a Jew prohibited by law, like all non-Catholics, from settling in Canada or other French colonies.

Some years earlier, the teen-aged Brandeau had been shipwrecked while traveling to Holland to visit family. Rather than return home to her parents in Bayonne, the free-spirited girl decided to experience the world, an adventure that could not then be undertaken by an unaccompanied female or a Jew. Masquerading as a gentile male, Brandeau spent the next few years working as a ship’s cook, a tailor, a baker, a gofer in a convent, a footman to an army officer, and finally a sailor. That the young woman had arrived in New France in drag did not seem to bother the authorities. Men so greatly outnumbered women in the colony that any addition to female ranks was welcome. That she was a Jew, however, was intolerable. Over the course of months, strenuous efforts were made to convert Brandeau to the “true faith.” But that was an adventure for which she was unprepared. In the end, she was sent home to her family. A decade later another young French-Jewish woman, Marianne Perious, arrived in New France disguised as a man. She, however, preferred life on the North American frontier to being Jewish and became a Catholic.

Brandeau and Perious provide a unique opening to the Canadian-Jewish experience. What has followed, however, has been more “normal.” Some two centuries ago, the poet Heinrich Heine noted that “As the Christians go, so go the Jews”; Jewish life tends to reflect the life of the majority non-Jewish society. And in Canada since the British conquest in 1759, that has largely been the case for both women and men.

THE FORMATIVE PERIOD

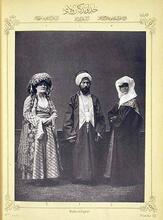

In many ways, Canada remained a frontier society throughout the nineteenth century and Canadian Jewry was a frontier Jewry. In 1851, after almost a century of Jewish settlement, there were only 354 Jews in all of Canada. Half a century later, there were 16,131, a Jewish population smaller than that of Buffalo, New York. Canada was still a country of wide open spaces; three-quarters of Canadian Jews lived in Quebec and Ontario, almost all of them in Montreal or Toronto. It was also a country that, despite its proximity to the United States, seemed to be perched on the periphery of civilization, certainly of Jewish civilization. As late as 1924, the militant Revisionist Zionist Ze’ev Jabotinsky considered Canada and Manchuria to be equally remote. It was a rather biting assessment, since he had recently visited Canada and had supporters there, and he had served with Canadians in the Jewish Legion during the World War I Palestine campaign.

Being situated on the New World frontier had different implications in Canada and the United States. The latter country was born in rebellion against the Old World and much that it stood for; Canada was born in fealty, first to ancien régime France and then to the British crown. Although it is a broad generalization, it may be said that for Americans, the frontier has meant valuing the new and untried over the customary, and the individual over the group. The frontier melting pot has offered Americans the opportunity to put the past behind them in order to create a new person and a new society. Until well after World War II, Canada reacted to frontier possibilities with conservatism, seeking to preserve the social and religious traditions of its two founding (European) peoples—Catholic French Canadians and Protestant English Canadians. The country remains politically tied to the British crown in 2006, and the template for Canadian society is the mosaic in which each ethnic and religious tile remains distinct while being part of the whole picture. Multiculturalism, which has been Canadian government policy since the 1970s, has broadened the mosaic conception; in theory, it was intended to strengthen it, although, as will be seen, that has probably not been its effect. Canadian conservatism has had implications for gender, ethnicity and religion, and it has shaped the experience of Canadian Jewish women over the years since Esther Brandeau first set foot on the soil of New France.

One aspect of Canadian (and not only Canadian) traditionalism has been a longstanding belief that women should take on the roles that traditional European societies assigned them, confining their activities to the private and personal spheres, preferably serving as helpmates to their husbands. Most professions and public affairs were considered neither “ladylike” nor “respectable” for the well-to-do. A 1920s article about the wife of an early twentieth-century rabbi at Toronto’s Holy Blossom Temple sums up this approach well. “Much of Rabbi [Solomon] Jacobs’ success,” the article asserts, “was due to the splendid co-operation and assistance given to him by his wife who dedicated her entire lifetime to welfare and philanthropic work” (Hart 256). Not surprisingly, these strictures were applied only loosely to the working classes and the petite bourgeoisie. To them, domestic service, child care, shopkeeping and, later, factory work, albeit not in heavy industry, were “permitted.”

One result of this attitude is that most Jewish women in Canada before the turn of the twentieth century and many after that elude the historian’s gaze. They are mentioned in the sources not for their accomplishments, but only as the wife, daughter or mother of a male family member. An eighteenth-century exception is Frances (David) Michaels (the widow of Myer Michaels), who made a large donation that enabled the tiny pioneer Jewish community of Montreal to build its first synagogue in 1777. Almost a century later, British Columbian Cecelia Davies (later Sylvester), when but a fifteen-year-old new immigrant from Australia and California, raised significant sums of money for the building campaign of Victoria’s first synagogue in 1863. The building was still in use by the congregation in 2006, the oldest synagogue building in continuous use in Canada. After her marriage, Mrs. Sylvester served on the executive board of the Royal Jubilee Hospital.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there were some notable examples of middle-class Jewish women who broke with prevailing norms and enjoyed successful professional careers, although mostly in the “respectable” fields of education, health and the arts. One of the first was a great-granddaughter of Aaron Hart (1724–1800), Canada’s pioneer Jewish settler, Caroline Hart, who headed the kindergarten department of the Toronto Normal School from 1885 to 1892 and is regarded as the founder of Toronto’s kindergarten system. Hart’s success notwithstanding, entry into education, a typical field of endeavor for second-generation Jews in the United States, was not easy for Jews of either gender in Canada. Until after World War II, school boards hired very few Jews. Religion permeated the “public” schools, and when boards did engage Jewish teachers, it was usually for the few schools in Jewish neighborhoods. The experience of Mary Frank (Zaritsky) is illustrative. After graduating from the Macdonald School for Teachers in Quebec in 1932, she discovered that there were no jobs for Jewish teachers in Montreal. She took a position in the two-room school of the Ste-Sophie Jewish farming colony.

University appointments were generally beyond reach in these years, as the experience of Mattie (Levi) Rotenberg demonstrates. In 1926, Rotenberg became the first woman and the first Jew to earn a doctorate in physics at the University of Toronto, and her dissertation was published in the Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada. From 1941 to 1968, she worked as a demonstrator in the physics laboratory of her alma mater; senior appointments in any field were rarely given to women and almost never to Jews.

An early success story, although rather idiosyncratic because it depended on great talent, is that of Pauline Lightstone (1882–1970), a well-known opera star. As Madame Donalda, she sang for decades at Covent Garden, the Manhattan Opera House, the Monte Carlo Opera and other houses, before returning to Montreal at the outbreak of World War II. Trained at the Royal Victoria College, she enjoyed the patronage of Lord Strathcona (Donald Alexander Smith, one of the chief promoters of the Canadian Pacific Railway) in honor of whom she took her stage name.

Of the healing professions, nursing was considered acceptable for women in these years, but doctors were men. Jews faced discrimination in both fields. A number of Canadian-Jewish women were trained as nurses; one of these was Leila Rapoport of Calgary, who distinguished herself on the home front during World War I. The first Jewish woman physician to be trained in Canada was Dr. Bessie T. Pullan (later Singer). After graduation from the Ontario Medical College for Women in 1909, Dr. Pullan did post-graduate study in the United States for two years and then returned to Toronto to practice. She was married to Louis M. Singer, a distinguished lawyer and sometime Toronto alderman.

A second aspect of Canadian traditionalism was segregation enforced mostly by social rather than legal sanction. In many respects, the various groups composing the society and polity of Canada have led quite separate lives. These include the French and English nationalities, the ethnic communities that followed them, and, of course, the first nations; the religious groups: Catholics (divided into French, Irish, and others), Protestants (divided into various denominations), then Jews, and finally Muslims and the adherents of non-Western religions; and also men and women. It was not the mosaic conception alone which engendered segregation in Canada. Ethnic, racial, religious and gender prejudice reinforced social theory.

Even when their numbers were very modest, Jews began to organize their communal life. Synagogues and cemeteries came first, followed by charitable, educational and political organizations. Synagogues included both women and men, although they have tended to the present day to be much more conservative than American synagogues and, as a result, more male-oriented. Leadership roles in Jewish prayer services everywhere remained a male preserve until the late twentieth century. But, in general, religion is often considered to be more of a women’s concern than a men’s. South of the border, a measure of frontier-life equality was introduced into synagogues early on. Mixed seating for men and women became the norm among Americanizing Jews—although not among more recent immigrants—at the beginning of the twentieth century, and sisterhoods and ladies’ auxiliaries often assumed a major role in congregational affairs before that.

In Canada, however, Judaism mirrored the traditionalism of the Christian churches. As late as 1953, there were only three Reform synagogues in the entire country. At the largest of these, Holy Blossom in Toronto, the 1894 constitution permitted only limited membership rights to widows and unmarried adult women and none at all to married women; separate seating at the most important services obtained until 1920; and only in 1921, some seven decades after the congregation’s founding, was a Temple Sisterhood formed to “espouse such religious and Jewish educational causes as are particularly the work of Jewish women” (Hart 271). These “causes” included operating a gift shop, assisting immigrants, and arranging pulpit flowers, lectures about children and Holiday held on the 14th day of the Hebrew month of Adar (on the 15th day in Jerusalem) to commemorate the deliverance of the Jewish people in the Persian empire from a plot to eradicate them.Purim and Lit. "dedication." The 8-day "Festival of Lights" celebrated beginning on the 25th day of the Hebrew month of Kislev to commemorate the victory of the Jews over the Seleucid army in 164 B.C.E., the re-purification of the Temple and the miraculous eight days the Temple candelabrum remained lit from one cruse of undefiled oil which would have been enough to keep it burning for only one day.Hanukkah celebrations. In Canadian Conservative synagogues, separate seating was the norm until after World War II, and in 2004 many of them did not yet include women in the prayer quorum. At the turn of the twenty-first century, the constitutions of some Toronto Orthodox congregations still restricted the number of women who could be elected to the congregational boards of governors to a fixed percentage of the male governors.

While for many years women took a back seat in the religious life of the community, in charitable work they early on assumed a prominent role. In Calgary, St. John, New Brunswick, Ottawa and some other communities, women organized the first Jewish charitable organizations. Caring for the poor and needy is considered a religious obligation in Judaism, and since it was an arena of activity considered appropriate for women in the nineteenth century, Jewish women channeled some of their religious fervor in that direction. In Toronto, the Hebrew Ladies’ Sick and Benevolent Society (later the Montefiore Hebrew Benevolent Society) was founded in 1868 by wives of Holy Blossom members. Some years later women from the congregation established the Dorcas Society to make clothing for the poor. (This was an odd name for a Jewish group. It was taken from the New Testament Book of Acts and was the name of a group of societies begun in Scotland for clothing the poor and Christian outreach.) In Hamilton, the women of Anshe Sholom Congregation set up the Deborah Ladies Aid in 1878.

By the turn of the twentieth century, women’s charitable societies were proliferating across the country differentiated from one another by task, class and their members’ place of origin in Europe. Most were not directly related to synagogues. In Montreal, the Ladies’ Hebrew Benevolent Society had been founded in 1877. It assumed responsibility for those tasks related to women and children performed until then by the Young Men’s Hebrew Benevolent Society, the roots of which dated back to 1843. The Toronto Hebrew Ladies’ Aid Society was established in 1899; it was one of the first societies in the city other than a synagogue to be founded by the newer immigrants of eastern-European origin. In this organization and many others, Ida (Lewis) Siegel was the driving force. Subsequently two groups—the Austrian Ladies’ Aid Society and the Polish Ladies’ Aid—broke away from the Ladies’ Aid, leaving behind women who were mostly wealthier, of longer residence in Canada and of Lithuanian origin. The Hebrew Ladies’ Aid was an organization acutely aware of prevailing social norms and communal political realities. “In view of the responsibility assumed by the Society, it was agreed [at the outset] that the President should be a man” (Hart 262). They were not the only women’s organization to coopt men in order to achieve their goals. In 1916, the Hebrew Ladies’ Aid was disbanded and its assets were transferred to the new Federation of Jewish Charities (later, the United Jewish Welfare Fund and now UJA/Federation).

In Winnipeg, the Girls’ Benevolent Loan Association with an all female roster of officers was founded in 1902 (?) to offer interest-free loans to girls and unmarried women. Between 1912 and 1920, the Hebrew Ladies’ Orphan Home Association (later the Ladies’ Society of the Jewish Orphanage), together with B’nai Brith and men and women donors from Fort William in Ontario to Vancouver on the Pacific Coast, established the Hebrew Orphans’ Home in Winnipeg. By 1925, the Ladies’ Society had some two thousand members who supported a modern building that could accommodate one hundred and fifty children. From the start, women and men served as officers of the Orphanage and on its board of governors. Among the early women officers was Sadye Rosner (later Bronfman).

In the large communities of Montreal and Toronto, a number of rather specialized women’s aid associations sprang up in the years between the turn of the century and the outbreak of World War I. Jewish Endeavour Sewing Schools were established in Montreal (1902) and Toronto (in 1912 the name was attached to an existing group) to teach young girls a marketable skill, provide a venue for socializing and religious indoctrination, and combat Christian missionaries who lured Jewish girls with the promise of vocational training and other emoluments. (This name, too, was odd. It came from the Christian Endeavor Movement begun in Portland, Maine by evangelical Protestants for outreach among “new” or “undeveloped” young Christians.) Other organizations included the Hebrew Ladies’ Maternity Aid Society of Toronto, founded in 1908 to “bring cheer” to women and children hospitalized in the Weston Sanatorium, and the Hester How [Public] School Mothers’ Club. The ostensible goal of the Mothers’ Club was to keep young girls from shoplifting on Saturdays, but really it was to provide a venue for instruction in Judaism. In both of these groups, Ida Siegel was the guiding spirit. Over time, the Mothers’ Club grew into the city-wide, non-sectarian Home and School Association. Some other women’s societies of the day were the Friendly League of Jewish Women in Montreal with its Welcome Club founded in 1913 to provide “wholesome pleasures … for the [female Jewish] toiler”; the Ezras Noshem (Women’s Help) Society of Toronto, also founded in 1913, which provided mutual aid to its members and a free loan society and in 1921 purchased a building to house the new Mount Sinai Hospital; and the Hebrew Young Ladies’ Boot and Shoe Society founded in Toronto in 1914. In addition to providing shoes for the poor, the Boot and Shoe Society “encouraged sports” among its members and offered them “practical demonstrations of art, literature, music, drama, communal work [and] social science.” It affiliated with the Federation of Jewish Charities in 1919 and disbanded in 1924 (Hart 261–262, 264, 268).

More wide-reaching in scope and more long-lasting than any of the foregoing were the Young Women’s Hebrew Association (YWHA, now the YM-YWHA) of Montreal established in 1910 and the YM-YWHA of Toronto (now the Jewish community centers) established in 1919. The Montreal Y was originally intended to provide a residence for young, single Jewish women as the YWCA did for gentiles. It closed in 1918 but reopened in 1920 with a broadened social and educational mission after merging with the Welcome Club of the Friendly League of Jewish Women. In Toronto, following several false starts, various clubs joined together in 1919 to offer activities for young men and women ranging from Friday evening lectures to Saturday night dances. Once again, Ida Siegel was the moving force; in the first few years of the Y’s existence, Adelaide Cohen served as executive director. By 1924, the Toronto Y had 1,100 members.

The Y movement came to Canada from the United States, although it had originated in England. It was one of several international groups to establish a Canadian beachhead in the early years of the twentieth century. The Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire was a non-Jewish society imported from England; in Canada, several all-Jewish chapters were established. The National Council of Jewish Women (NCJW) was imported from the United States. The Council had emerged from the women’s activities organized during the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. It attracted middle- to upper-middle-class women, often adherents of Reform Judaism, interested in social service to Jews and gentiles. The NCJW was brought to Canada in 1896 by Katie De Sola, the wife of the stridently Orthodox Rabbi Meldola De Sola of Montreal’s Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue. A Toronto section established in 1897 with the help of Mrs. De Sola assisted the Red Cross during World War I and the influenza epidemic of 1918, offered aid to immigrants and instruction in English and citizenship over the years, and sponsored the Jewish Girls’ Club which had over a thousand members by the mid–1920s. A Montreal section of the Council founded in 1918 undertook to work with juveniles and immigrants, inaugurated a Big Sister program in 1920, set up a recreation program in the 1920s in schools in Jewish neighborhoods and sponsored summer camps in the Laurentians for young girls. In the 1920s, NCJW sections were established in Edmonton, Calgary, Vancouver and elsewhere in Canada. In 1927, the Vancouver section of the Council opened a Well Baby Clinic, and since 1922 the Toronto section has maintained a “council house.”

In 1924 the Montrealers declared their independence from the American parent organization and from that time the Canadian Council members began to assert their autonomy. In 1937 the first all-Canadian convention of the NCJW was held in Winnipeg. In 1940 the Council boasted a membership of over two thousand women and six hundred “juniors.” At that time it claimed to be “the only [national] Jewish organization in Canada concerned [exclusively] with local and national [rather than Zionist] problems.”

World War I provided the impetus for new women’s activities including the Soldiers’ Comfort League, headed by Anna Selick of Toronto, a social worker and pioneer Zionist. The League was established “to provide comforts for the members of the Jewish Legion who saw service in Palestine.” (North American recruits trained in Canada before being shipped overseas.) In Winnipeg, the Mogen Dovid Society raised “funds for the relief and comfort of the Jewish Legionnaires.”

The most celebrated, but in some ways the saddest, undertaking of the war period involved bringing Jewish war orphans from Ukraine to Canada. While both women and men were involved in the rescue effort, Lillian Freiman, one of Ottawa’s foremost civic leaders and Canadian Jewry’s most prominent woman, spearheaded the movement as chair of the Jewish War Orphans Committee of Canada. It was estimated in 1920 that some 137,000 Jewish children had been orphaned in Ukraine during the war and subsequent pogroms. An ad hoc committee of Canadian-Jewish notables decided to bring one thousand of the children to Canada and a highly publicized campaign for funds and foster parents was mounted. The government, however, gave permission for only two hundred. The official who fixed the quota was Frederick C. Blair, secretary of the Department of Immigration and Colonization. He was the man who would stand guard at the gates during the Holocaust era, ensuring that fewer Jews in relation to its population would enter Canada than any other Western country. In the end, partly because of a cautious, cumbersome selection process, only 146 orphans came to Canada (one girl was adopted by Mr. and Mrs. Freiman) and another ten to the United States, although considerable quantities of food and clothing were sent to those left behind in Europe. That carefully planned and executed publicity and lobbying by some of Canada’s best-placed Jews—including the Freimans—had accomplished so little illustrated the political impotence of Canadian Jewry as well as the power of better- placed antisemites, although few Jews at the time recognized the extent of the problem. In some ways, the affair was a rehearsal for the Holocaust period.

While charity and social service work were the central concerns of a large number of Canadian-Jewish women until well after World War II, political activity, often combined with social service, attracted an increasing number in the formative years of the community. At the turn of the twentieth century, Annette (Pinto) Joseph (Mrs. Montefiore Joseph) was a life member of the Navy League in Quebec City. Aimee (Lyone) Green was a member of the Winnipeg Civic Club and served as one of two Manitoba representatives on the Dominion Executive of the Liberal [Party] Ladies’ Clubs. (Her husband, S. Hart Green, was elected to the Manitoba legislature in 1910, the first Jew to sit in a provincial legislature since Confederation.) Some years later, Ida Siegel was elected a trustee of the Toronto Board of Education, but she failed in a subsequent bid for an aldermanic position.

Most politically engaged Jewish women in these years worked within the Jewish community. In 1910 in Montreal and in 1917 in Toronto, Jewish women rose up in protest against the rising price of Term used for ritually untainted food according to the laws of Kashrut (Jewish dietary laws).kosher bread. In Toronto, a boycott was declared and picket lines set up in front of the bakeries and the groceries and restaurants they served. On more than one occasion, women forcibly removed bread from shelves and display cases, and deliveries were suspended for a time out of fear for the drivers’ safety. Prices in both cities were eventually lowered but more as a result of market forces than because of the strike. More successful were kosher meat boycotts in 1924 and 1933.

While the bread and meat protests were not solely the products of leftist protest, union activity, socialism and communism did have many adherents in Canada’s Jewish communities in the turn-of-the-century years, especially among the large number of immigrant blue-collar workers in the needle trades. One might expect to find leftist organizations operating according to egalitarian principles and to some extent they did. Jewish women played a role in union activity together with Jewish men and with gentiles and participated in a number of strikes. Women were even more exploited than men in the garment industry, and, according to labor historian Irving Abella, “no strike would have been possible without their support.” Perhaps the bitterest of these was the Montreal garment workers strike of 1917 which lasted almost half a year and erupted into violence on a number of occasions, some of it “perpetrated by Jewish women” strikers. And yet, Abella notes, women “were allowed to play only a minimal role in the Jewish trade unions.”

Not only were organizations of the left not necessarily egalitarian in practice; often they adhered to prevailing Canadian social norms with regard to segregating Jews from gentiles and men from women. And they were not immune to prejudice. The Labour League (later UJPO, the United Jewish People’s Order) was a workers’ communist front organization with branches in Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg, Vancouver and some smaller centers. It was a breakaway from the Workmen’s Circle, a socialist, Yiddishist organization that had its origins in New York. The League was, in fact, a men’s league; women workers were organized in the Jewish Working Women’s League, which remained affiliated with the Workmen’s Circle in part to avoid becoming a ladies’ auxiliary of UJPO. Another example is Toronto’s Jewish, communist Freiheit Club, which, beginning in 1923, directed its women members into the Jewish Association of Progressive Women with responsibility for children’s activities. The women ran a summer camp and from 1925, Sabbath morning classes in Marxist ideology.

Of the various pre–1920 Jewish organizations and movements, the one that early on accorded women a position of power was the Zionist movement. The idea of a national revival in the ancient Jewish homeland gradually gathered force in Europe and elsewhere in the Jewish world in the latter half of the nineteenth century. In Canada, it achieved instant and universal popularity among Jews, who increasingly felt themselves to be an anomaly in their country of residence, neither French nor English, neither Protestant nor Catholic. As Molly Lyons Bar David, a columnist in the American Hadassah Newsletter who immigrated to The Land of IsraelErez Israel from western Canada, observed, perhaps with a tinge of irony, Canadian Jews “were not plagued by the idea of dual loyalties as many American” Jews were. By 1899, just two years after the founding of the World Zionist Organization, some twenty-five percent of Montreal Jewish males had joined the movement and in that year Toronto’s first women Zionists came together as the Daughters of Zion. Except for fringe circles of the far left and a few idiosyncratic individuals, Zionism has never encountered serious opposition among Canadian Jews.

From the early 1900s to the 1930s the Federation of Zionist Societies in Canada (FZSC—later, the Zionist Organization of Canada, ZOC, and then the Canadian Zionist Federation, CZF) served as the national representative organization of Canadian Jews and the community spokesman. Until the sixteenth convention of the FZSC in 1919, “women, as Zionists, participated” fully in its activities at every level. To be sure, a number of separate women’s organizations emerged in the early years of the movement: Daughters of Zion in a number of cities, B’noth Zion Kadimah groups, Herzl Ladies’ Societies, Herzl Girls, Red Mogen David, Nordau Girls, De Sola Girls, the Young Ladies’ Progressive Zionist Society, the Jewish Women’s League for Cultural Work in Palestine, Hadassah and others. But women “were also members of the main body to which they paid per capita dues.” In 1901, Esther Feldstein was elected to the national Council of the FZSC for the first time. In 1903, Belle Maude De Sola of Montreal, the wife of Clarence I. De Sola, the FZSC president, Mrs. Manolson of Montreal, Ida Lewis (Siegel) of Toronto, and Mrs. Livingstone of Ottawa were elected FZSC vice-presidents, and Siegel remained in office until 1911. In 1908, Anna Selick was elected vice-president of the Toronto Zionist Council and later a member of the National Executive of the ZOC. In the 1920s, Rose Dunkelman served on the ZOC National Executive. Women were certainly “under-represented” in the Federation in those years, and after 1911 they were not elected to major national office until the ZOC was reorganized in the 1920s with regional representatives. But this was still a greater level of equality than in any other major Canadian-Jewish organization of the time.

Following visits to the Toronto Daughters of Zion in 1917 and 1919 by Henrietta Szold, the founder of Hadassah in the United States, the Hadassah idea began to spread rapidly in Canada spearheaded by Anna Selick. In 1916 Hadassah was a group of ten Toronto women; eight years later it was a Dominion-wide federation of 4,500 members raising some $45,000 CDN annually for work in Palestine. In 1919, Lillian Freiman “readily consented to become the generalissimo” (national president) of Hadassah. In 1921, she was officially elected Hadassah president and served until her death in 1940. Her successor was Anna (Selick) Raginsky.

Under Freiman’s guidance, Canadian Hadassah severed its connection with American Hadassah and affiliated with WIZO, the Women’s International Zionist Organization, a group headquartered in London and led by the wives of British Zionist leaders. The Canadians assumed the name Hadassah-WIZO, which indicated not only their dual origins, but also the role Canada so often played as a bridge between Britain and the United States. Szold never forgave the Canadians, especially Freiman, for what she perceived to be treachery and ingratitude for the “effective and wholly unselfish” assistance given them by “Hadassah in America.” But the very American Szold was not sensitive to Canadian fears of being swallowed up by the United States, nor did she understand the importance of Canada’s British connection. For all Anglo-Canadians, British ties provided Old-World roots and legitimacy. For Jews caught between French and English, this was not inconsequential. And since Britain was the occupying power in Palestine and had issued the Balfour Declaration, the British link was a way to short-circuit any possible accusation of disloyalty.

Over the years, Hadassah-WIZO became the largest Jewish women’s organization in Canada, although, unlike the American Hadassah, it did not overshadow the ZOC and was largely apolitical. Its first major project was the Helping Hand Fund for Destitute Jewry in Palestine headed by Freiman. Fund raisers combined sophisticated advertising techniques with personal canvassing to great success. Freiman barnstormed across the country in 1919, and the largest sum to date of any Canadian-Jewish charitable campaign—over $159,000 plus $20,000 ($40,000?) worth of clothing—was raised. In 1921, Junior Hadassah for younger women was founded, and two years later, Hadassah-WIZO adopted the Agricultural Training Farm for Women at Nahalal. Later, Hadassah-WIZO joined American Hadassah in support of Youth Lit. "ascent." A "calling up" to the Torah during its reading in the synagogue.Aliyah and then of Israeli hospitals.

In 1923, Rose Dunkelman spearheaded the establishment of Hadassah Mascots for young girls. According to a contemporary observer, the Mascots occupied “somewhat the same relation to the main Hadassah organization as the Boy Scouts do to the regular soldiers.” A year later, Dunkelman initiated the annual Hadassah Bazaar in Toronto at which new and used donated articles were sold by volunteers with all the profits going towards Hadassah projects in the land of Israel. By 2004, the Bazaar was regularly held at the Canadian National Exhibition and was a well-established Toronto institution.

During World War II, Hadassah-WIZO reoriented itself towards Canada to a degree. The organization furnished hostels for soldiers, purchased ambulances for the Canadian troops and worked with the Canadian Red Cross. The group also equipped a thirty-bed hospital ward in Britain and a hospital in Palestine for British soldiers serving there. In 1949, the organization undertook to furnish the first Israel consulate in Montreal.

In addition to Hadassah-WIZO, Zionist women’s organizations in Canada include the Pioneer Women’s Organization and Emunah Women. The Pioneer Women, a Labor Zionist group which had begun in the United States, first branched out to Canada in 1925. Its main goals were to raise funds for the support of working people’s institutions in the land of Israel and to sponsor the Habonim Youth Movement in Canada and the United States. In the 1930s, Goldie Myerson (Golda Meir) visited Canada on several occasions to speak to Pioneer Women chapters. In the 1960s Pioneer Women Canada became independent of the American parent organization.

Before World War II Canadian Zionists, both men and women, dedicated themselves chiefly to fund raising, but they also encouraged fulfillment of the Zionist ideal by taking up residence in Palestine. Although the number of Canadian Jews that immigrated in those years was small, it included a few women. One was Montrealer Goldie Joseph, whose husband, Bernard (later Dov Yosef), also a Montrealer, played an important role during and after Israel’s War of Independence. Another Canadian émigré was Sylva Gelber, the enormously talented but restless daughter of a prosperous, patrician Toronto family involved in Zionism and Jewish life in general. After being rejected by Barnard College in New York because the “Jewish quota … was already filled,” she tried her hand at Jewish journalism, acting and study but without finding fulfillment. Unable to find a place for herself in Canada and unable to afford living in New York, she decided to try Palestine in 1932, becoming the first graduate of the Hadassah School of Social Work established by Henrietta Szold. Gelber returned to Canada just before Israel became independent.

Canadian Jews were pulled towards Palestine out of romantic idealism and loyalty to the Jewish people, but also because “the fate of the new Jewish settlements . . . . [there was] bound up with the fate of Great Britain,” Canada’s mother country. They were pushed in that direction because, to a larger degree than in the United States, they felt themselves “alien to their surroundings,” as Chaim Arlosoroff, the Zionist emissary, noted after a visit to western Canada in 1928.

A CHANGING COMMUNITY IN A CHANGING COUNTRY

When Canadian society began to open up and prejudice to diminish is hard to pinpoint; when the boundaries demarcating Canada’s various ethnic, religious and gender groups began to become somewhat fuzzy is even harder to determine. Although World War II and its accompanying dislocations had an effect, change did not seem very evident at the time. Contributing to the fight against Nazi Germany involved “joyful offerings of time and self” for Canadian-Jewish women, as may be imagined. And yet, the Red Cross permitted them to participate in its activities only through a segregated “Jewish Branch” or through independent Jewish groups, such as Hadassah-WIZO and the National Council of Jewish Women, which turned over funds or handiwork to the gentile organization. Earth and High Heaven (Toronto: 1944) was a best-selling novel by a highly regarded Canadian novelist, Gwethalyn Graham. The heroine of the story is an upper-class Montreal WASP, a capable and successful newspaper journalist whose sexist boss has pigeonholed her on the society page. (In the same years, physicist Mattie Rotenberg was a regular commentator on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s “Trans-Canada Matinee,” a program dedicated to women’s issues.) The plot of Earth and High Heaven centers around the impediments encountered by those who wish to marry across the Canadian religious and ethnic divides (French/English and English-Protestant/Jewish). The novel ends with the boundaries crossed, but it is a work of protest, a polemic against the unlikelihood of such an event occurring in wartime Canada, not a celebration of reality. And, as noted earlier, during the Holocaust era Canada shut its doors in the faces of Jewish refugees, women and children no less than men.

Beginning in the 1950s, some changes could be perceived. For one thing, the sense of living in a frontier community began to dissipate as Canada took a prominent role in international affairs (the Palestine partition question, for one), and as Canadian Jewry grew into one of the world’s largest and most prosperous communities. By the year 2005, Canada no longer appears to be guided by the conservative impulse to preserve the traditions of the past. The country’s openness to immigrants from Africa and Asia, the decline of religious practice among many Canadians (Catholic Quebec now has the lowest birth rate of any Canadian province), the 2004 Supreme Court ruling and subsequent legislation legalizing gay marriage, the concern with inclusiveness in most social and political institutions, the outlawing of capital punishment, a fairly permissive approach to soft drugs and sexual relations, all point away from the old Canada and towards a new reality in the making. With regard to women, from the late 1960s feminist notions including personal fulfillment and equality and the devaluation of life as a home maker contributed to the erosion of conservative Canadian attitudes.

Feminist scholar Sheva Medjuck has argued that there is no inherent conflict between the values of Judaism and those of feminism. But there is no question that middle-class Jewish women now shifted some of their energies from volunteering in the community to working in the market place and from family to career. And many began to work towards equality in Jewish religious life which more traditional Jews strongly opposed. On the other hand, a 1991 survey of Montreal Jews revealed that eighty percent valued most highly a happy marriage and raising a family (women more than men with regard to the second), while fewer than half considered “being outstanding in one’s field of work” a very high priority (rather more in the 18 to 29 age cohort without much gender differentiation). And while Medjuck and others claim that single women have no proper place in the Jewish community, a Toronto survey of single Jewish mothers seems to indicate that the problems they encounter have much to do with the objective difficulties involved in juggling roles and finances rather than communal attitudes. Like other Canadians, most, although certainly not all, Jews of the late twentieth century were more relaxed about their traditional values than their forebears.

A variety of social and legal developments influenced the new attitudes towards and of Canadian women and Jewish women, in particular. The adoption of the new Canadian constitution and the attendant Charter of Rights and Freedoms at the beginning of the 1980s was a milestone in the process of change, shifting emphasis from the group to the individual. As Lorraine Weinrib has pointed out, Jews played a significant role in the constitutional process. To a degree, the embarrassment of non-Jews regarding Canada’s role during the Holocaust also helped to alter public opinion. The Constitution, the Charter and legislation regarding hate crimes and hate speech signaled a shift of attitude regarding Canadian segregation and served to undermine its legal foundations. Multiculturalism, which in the 1970s replaced the two-nations concept of Canada enshrined in the quasi-constitutional British-North America Act of 1867, may also have served to weaken the barriers separating the different sectors of Canadian society. The multiplicity of ethnicities and religions in post-l960s Canada may have encouraged a kind of relativism regarding issues of culture and nationality which subverted fealty to one’s group of origin. Moreover, the many groups could not all exercise meaningful autonomy without creating social, cultural and linguistic anarchy.

Notwithstanding social change, in many ways the communal life of Canadian-Jewish women has retained a recognizable shape from the earlier period. At the local level, many of the older organizations have ceased to exist or have been folded into larger, usually mixed-gender agencies. This is especially the case regarding welfare and education, where needs have shifted and a high degree of professionalization is now called for. But new local agencies have emerged, and the most prominent of the older organizations, especially those on the national scene, remained active in 2004 showing evidence of being able to shift priorities and adopt innovative programs.

It is sometimes asserted that volunteerism has declined in North America as a result of feminism, but in Canada it remains at a fairly high level among Jews and higher among Jewish women than among their male counterparts. It has also been suggested that the average age of “joiners” in voluntary organizations has risen considerably, which is probably the case, especially in synagogue sisterhoods. Still, in 2004 Hadassah-WIZO claimed a membership of fifteen thousand women and one thousand male “Life Associates” in thirty-four cities across the country. As it has since its inception, Hadassah continues to provide generous support for institutions in Israel including innovative projects to meet changing needs, such as the Youth Lit. "ascent." A "calling up" to the Torah during its reading in the synagogue.Aliyah Child Guidance Clinic in Jerusalem. Na’amat Canada (formerly the Pioneer Women) engages in a range of Israel-oriented activities, and the Emunah Women are stronger than ever as a result of the increasing strength of Orthodoxy in North America. In addition to fund raising, Emunah sponsors a Rosh Hodesh (first day of the month) lecture series for women in Montreal.

The National Council of Jewish Women also retains considerable vitality and has responded to new—or newly recognized—needs. Working with immigrants and aid to the needy remain concerns of the Council; in Toronto, the annual A seven-day festival to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nissan. Also called the "Festival of Mazzot"; the "Festival of Spring"; Pesah.Passover Food Drive is one of its best known activities. Since 1985, the Montreal group has sponsored Auberge Shalom, the first Jewish women’s shelter in Canada. Established in response to the murder of a local Jewish woman by her husband in 1984, the shelter deals generally with domestic abuse, a phenomenon often acknowledged only reluctantly in the Jewish community. In 2004 the shelter felt the need to hire an Orthodox professional to deal specifically with that sector of the community. Emergency shelters are also maintained in a number of cities by Jewish Women International, formerly B’nai Brith Women.

In the late 1980s the NCJW gained unexpected notoriety, when the former president of its Toronto section, Patricia (Patti) Starr, was accused of diverting organization funds illegally to the Liberal Party and engaging in other corrupt practices. Starr, who had used her work with the Council as a stepping stone to a political appointment and a position as fund raiser for the Ontario Liberals, was convicted and served a short jail sentence. The scandal touched two other Jewish women who were Liberal politicians: Elinor Caplan, the provincial Minister of Health, and Chaviva Hosek, the provincial Minister of Housing. Both were accused of colluding with Starr in illegal acts, as was the provincial premier, David Peterson, but the accusations were never proved. While the entire Jewish community was embarrassed by the affair, looking back, it can be seen as an indication of the degree to which Jewish women had become integrated into Canadian politics.

As fund raising in the major communities became increasingly centralized after World War II, special campaign divisions for raising funds from women were created in the 1960s by the United Jewish Appeal (Combined Jewish Appeal in Montreal). The assumption underlying those divisions was that although middle-class women did not have independent control of large sums of money, most would be willing and able to give gifts supplementary to those of their husbands. Although an increasingly large number of women earn substantial salaries or control considerable fortunes, the women’s divisions have persisted under various names.

Education is an area of community activity where much innovation has taken place in recent years with regard to women. Separate schools for ultra- and modern-Orthodox girls are not new, but in Toronto especially they proliferated in the late 1990s and early 2000s, often with only minute distinctions differentiating one from the other (families with television at home and those without, for example). More interesting, perhaps, are some new thrusts in adult women’s education, particularly in Toronto. One is the Mekorot Institute of Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah Study for Women, which aims “to make a full range of traditional Jewish texts available [in] … an atmosphere of spiritual and intellectual growth.” Mekorot is loosely modeled on the Drisha Institute of New York; the teachers are both men and women. Two Orthodox Toronto women, Rachel Turkienicz and Shoshana Zolty, conduct study programs for adult women. Both have a B.A. from York University and doctoral degrees from Brandeis and the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education respectively; both aim to deepen women’s knowledge and spirituality through the study of classical Jewish texts in an intimate atmosphere. Another new educational initiative in Toronto is Kolel, the Adult Centre for Liberal Jewish Learning. Founded in 1991 by Rabbi Elyse Goldstein, the first woman to serve as a rabbi at Holy Blossom Temple, Kolel “encourages [women and men] students to experience, learn and understand traditional Jewish thought and practices and apply them in our modern world.” Funded at first by Toronto’s Reform congregations, Kolel has become independent and, to a degree, non-denominational. In Montreal, Arna Poupko served as Federation scholar in residence in the 1990s. More recently, the Torah MiTzion network of Orthodox Zionist academies, which aims “to provide classes and chavruta [buddy-system] learning for [young, male, Orthodox] members of the community,” established a branch in Montreal. Classes for women taught by young men from Israeli yeshivahs were also being offered several times each week in 2005.

An example of innovative women’s organizational work in the latter years of the twentieth century is lobbying for the reform of Jewish divorce practices. The Canadian Coalition of Jewish Women for the Get under the leadership of Evelyn Brook has become a highly visible and effective pressure group which has succeeded in sensitizing the community to the problems faced by Jewish women whose husbands refuse to grant them the religious divorce required by Orthodox and Conservative Jews and by Israeli law before a woman may remarry (agunot). Within the community, there has been broad support for change, but some Orthodox rabbis seem to feel that ancient privilege should be upheld. Where the group, acting together with many other groups and individual women and men, has had unqualified success is in effecting legal relief for agunot through an amendment to the Canada Divorce Act passed in 1990. The amendment makes it very difficult for anyone to prevent a remarriage from taking place, a legislative step possible in Canada, where the wall of separation between church and state is less high than in the United States. Ironically, however, the resorting to civil enforcement of Jewish law (The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhah), while undoubtedly necessary, serves to undermine the authority of the community. Relief for agunot is yet another milestone in Canadian Jewry’s movement away from its frontier origins. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the country had been famous as a haven for Jewish men who had abandoned their wives in Europe or the United States.

Many Jewish organizations in recent decades demonstrate both continuity and change with regard to segregation. They remain exclusively Jewish, but they are no longer exclusively male. Community institutions, national and international organizations, and synagogues in which women were once accorded only a supporting role, have become increasingly integrated in the turn-of-the-millennium years, and women are now among the leaders. The Allied Jewish Community Services (now CJA/Federation), Montreal’s major community Jewish agency, elected its first woman president, Dodo Heppner, in 1983. She was followed by Maxine Sigman (1989–1991) and Marilyn Blumer (1999–2001). Dorothy Zalcman Howard headed the Canadian Jewish Congress Quebec Region for a term at the turn of the millennium. In 1995, Sandra Brown became the first woman president of the Jewish Federation of Greater Toronto (later UJA/Federation), after occupying a number of key policy-making positions in the community. (Rose Wolfe, a philanthropist who was later appointed chancellor of the University of Toronto, a largely ceremonial position, served as president of the Toronto Jewish Congress, a short-lived transitional phase of UJA/Federation, from 1978 to 1980.) The president (now chair) from 2003 to 2005 was Leslie Gales. The Vancouver Federation has also been led by a woman. From 1987 to 1990, Montrealer Dorothy Reitman served as president of the Canadian Jewish Congress, the first woman to head the national representative organization of Canadian Jews. Goldie Hershon, also from Montreal, served in the same post from 1995 to 1998.

Internationally, Canadian-Jewish women have assumed leading roles in recent decades in new organizations and in others which were once led almost exclusively by men. Women were in the forefront of the Struggle for Soviet Jewry in the 1980s; individuals such as Wendy Eisen, Jeannette Goldman and Genya Intrator were among the leaders of the movement and were supported vigorously by women’s groups including the National Council for Jewish Women. Judy Feld Carr’s largely one-woman, ultimately successful, twenty-five-year battle for the freedom of Syrian Jews is both remarkable and unusual. Beginning in the early 1970s, Carr succeeded in securing the right to emigrate for almost the entire Syrian-Jewish community. Most notably, Canadian Jews, both men and women, have been engaged with Israel. The involvement of women’s organizations has already been mentioned; among individuals, Julia Koschitzky stands out. In addition to the many responsibilities she has assumed in the Canadian-Jewish community over the years, she chaired the World Board of Trustees of Keren Hayesod from 1992 to 1997 and in 2003 she co-chaired the Education Committee of the Jewish Agency for Israel, perhaps the most important organization for Lit. (Greek) "dispersion." The Jewish community, and its areas of residence, outside Erez Israel.Diaspora-Israel cooperation.

In the once all-male preserve of worship, there has also been considerable change. The first woman to serve as president of a Canadian synagogue (1950–1953) was Victoria, British Columbia businesswoman, Anna Mallek. In 2004, only a few Canadian Orthodox synagogues allowed women to serve in that capacity, but almost no Conservative, Reform and Reconstructionist synagogues any longer place obstacles in the path of women aspiring to office. Since the mid–1980s women have served continuously as (assistant or associate) rabbis at Holy Blossom Temple in Toronto; in 2003 Rabbi Tina Greenburg became rabbi of that city’s Reconstructionist congregation, Darchei Noam. Over the years, a number of other Toronto synagogues have engaged woman rabbis and cantors and women have served in rabbinic posts in Vancouver, Halifax and elsewhere in Canada. With regard to the prayer service, women are now freer to express themselves directly. New rituals involving women, such as the Lit. "daughter of the commandment." A girl who has reached legal-religious maturity and is now obligated to fulfill the commandmentsbat mitzvah celebration when a girl turns twelve and the simhat bat celebrating the birth of a girl, are coming into general use, and greater involvement of women in synagogue worship is occurring in all denominations, ranging from full participation in egalitarian synagogues to annual special events such as dancing with the Torah scroll on the Lit. "rejoicing of the Torah." Holiday held on the final day of Sukkot to celebrate the completing (and recommencing) of the annual cycle of the reading of the Torah (Pentateuch), which is divided into portions one of which is read every Sabbath throughout the year.Simhat Torah holiday in some Orthodox synagogues. The first all-women’s prayer group in Canada started in Montreal in 1982 and has since been meeting each month, in Sha’ar Hashomayim and the Spanish and Portugese Synagogue, both Orthodox congregations. In 1993 the group published its own prayer book. Women’s seders have been held in various places on Passover, and for several years Toronto feminists celebrated the Lit. "booths." A seven-day festival (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Tishrei to commemorate the sukkot in which the Israelites dwelt during their 40-year sojourn in the desert after the Exodus from Egypt; Tabernacles; "Festival of the Harvest."Sukkot festival in a Booth erected for residence during the holiday of Sukkot.Sukkah by the Water which aimed especially to reach out to disaffected Jewish women. Among the chief organizers of that event was Toronto Star columnist Michelle Landsberg, the wife of Stephen Lewis, once Canada’s ambassador to the United Nations General Assembly.

More dramatic than the changes in Jewish community life are those that have occurred in the lives of Jewish women participating in the larger Canadian society. The change is three-fold. In 1931, about a third of Canadian-Jewish women worked at blue-collar occupations. Four decades later, that number had diminished to about six percent. Second, by the late twentieth century, Jewish (or other) women of the middle class were no longer restricted to “ladylike” careers or to the private realms of activity. And finally, it is no longer the case that female or male Jews are restricted to a limited number of professions or to the Jewish community as a venue for volunteer service.

By the turn of the millennium, Jewish women were participating in many areas of urban, middle-class Canadian life from business and the media to the arts, politics, the civil service and academia. In a few fields, their presence is striking. One is politics at the provincial and federal levels, mostly in the Liberal Party to which Canadian Jews have tended to gravitate since early in the twentieth century. Journalist Simma Holt served in the federal Parliament from 1974 to 1979 from Vancouver-Kingsway, Sheila Finestone from 1984 to 1997 from Mount Royal (Montreal), the riding once represented by Pierre Elliott Trudeau and in 2005 by Irwin Cotler; Elinor Caplan served from 1997 to 2004 from Thornhill (suburban Toronto) and was succeeded by Susan Kadis. In 2005, sitting Jewish women mps in addition to Kadis were Raymonde Folco representing Laval-les Iles, a Montreal riding, first elected in 1997, and Anita Neville from Winnipeg South Centre, first elected in 2000. All are Liberals. Finestone and Caplan were elected from ridings with large Jewish populations; both were appointed to cabinet, Finestone as (junior) Minister of Canadian Heritage and Caplan as Minister of Citizenship and Immigration and then Minister of National Revenue. In the civil service, Sylva Gelber enjoyed a distinguished career after her return from Palestine. Among other posts, she directed the Women’s Bureau of the Canada Department of Labor from 1968 to 1975 and served as Canada’s representative to the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women during much of the same period. Sylvia Ostry served as chief statistician of the Government of Canada from 1972 to 1975, deputy minister (chief civil servant) in the federal Ministry of Corporate Affairs from 1975 to 1978, chair of the Economic Council of Canada in 1978 and 1979 and in other positions. Several Jewish women have been nominated to judgeships over the years, most notably Rosalie Abella, the daughter of Holocaust survivors and wife of a historian of Canadian Jews. She was named to the Supreme Court of Canada in 2004. Abella is widely respected for her concern with human-rights law. In 2000, Myra A. Freeman was appointed lieutenant governor of the province of Nova Scotia, the first Jew to occupy that post in any province. A respected educator and community worker, Freeman is a publicly identified Jew who, among other things, has installed a Term used for ritually untainted food according to the laws of Kashrut (Jewish dietary laws).kosher kitchen in government house in Halifax.

In academia, Jewish women include professors in a variety of disciplines, and many of them take an active role in Jewish affairs. A few of the most notable in 2004 were Ruth Wisse of McGill and then Harvard, one of the foremost experts on Yiddish literature and an outspoken neo-conservative advocate for Israel; Lorraine Weinrib of the University of Toronto Law Faculty, one of Canada’s most highly regarded constitutional scholars and a consultant to Israeli jurists; Norma Baumel Joseph of Concordia University, a leading feminist activist, Orthodox Jew and Jewish Studies scholar; Adele Reinharz, a Bible scholar and University of Ottawa administrator; and Sara Horowitz, director of the Centre For Jewish Studies at York University and a respected scholar of Holocaust and women’s literature. In 2002 Heather Munro Blum was appointed principal (equivalent to president) of McGill University, one of Canada’s oldest and most prestigious institutions of higher learning, succeeding Bernard Shapiro, also a Jew. Judy Rebick, who in 2004 held an endowed chair in Social Justice at Ryerson University in Toronto, is an activist who was one of the founders of the Ontario Coalition for Abortion Clinics and who served as president of Canada’s largest women’s group, the National Action Committee on the Status of Women, from 1990 to 1993. Since 2002, Rebick has spoken out forcefully against both antisemitism and Israeli policies with regard to Arabs.

As Canadians have moved farther from their European origins, and as many once vibrant smaller communities decline, nostalgia combined with a growing appreciation of the Canadian past have sparked interesting initiatives, especially in the maritime provinces. In several cities, museums have been established to commemorate aspects of Canadian history, and Jewish women have been the driving force behind these institutions. In New Brunswick, Marcia Koven was the founder and long-time curator of the St. John Jewish Historical Museum, the only Jewish museum in Atlantic Canada, which opened in 1987. In Nova Scotia, Nina Cohen founded the miners’ museum of Glace Bay, and Ruth Goldbloom spearheaded the Pier 21 Museum in Halifax which opened in 1999 and documents the arrival in that port city of over a million immigrants from Europe, including, of course, many Jews.

An interesting field in which to take the measure of Jewish women in Canada is literature. Among the significant Yiddish poets and prose writers who have lived and written in Canada are several women, most notably Ida Maze (Maza) in the 1930s and Rochel Korn and Chava Rosenfarb (once married to Canada’s pioneer abortion activist, Henry Morgentaler), who came later. Among the most highly regarded postwar Canadian writers, there was a significant number of women, including Gabrielle Roy, who wrote in French, and Margaret Laurence, Mavis Gallant, Margaret Atwood, Alice Munro and Adele Wiseman, who wrote in English. Among the women, only the last was Jewish, and her output was very slim. In the same years, some of Canada’s best-known men writers were Jews: Mordecai Richler, Irving Layton and Leonard Cohen, to name only three, all of whom published prodigiously. The question why only one Jewish woman succeeded in reaching the front ranks of Canadian-Jewish, English-language writers in the postwar years begs to be answered.

The answer may, of course, be talent or the luck of the draw. But it may also have something to do with being a Jewish woman in Canada. Wiseman and her peers, such as Miriam Waddington and others, grew up in a community “totally at home in the European context of ethnic authenticity. … Jewishness still permeated every aspect of daily existence.” Born in Winnipeg, Wiseman was rooted in Jewish culture and the segregated Jewish experience of the Canadian mosaic—although not in Jewish belief. Such rootedness nurtured her literary imagination, as is evident in her first and best novel, The Sacrifice (Toronto: 1956). But from her personal life, Wiseman knew the special difficulties faced by all woman writers: “marital difficulties related to their writing careers;” frustrated sexual desire; childlessness as the only way to personal freedom and a career; facing the envy of a frustrated writer-spouse; and doing the “endless, repetitious, taken-for-granted labor that is the lot of the housewife and mother.” And for a Jewish woman who accepted many of the values of the Jewish community and family, these problems were exacerbated. Wiseman had close, traditional, “Jewish” relationships with her parents, siblings, daughter and, for a time, with her husband, and she felt responsibility for Jewish continuity after the Holocaust. She was pulled in many directions, never entirely free to follow her muse. For such a person, the cost of a writing career might well be very high, as it was for Wiseman.

Her second novel, Crackpot (Toronto: 1974), was fifteen years in the writing. During that period, she held a teaching job and had primary responsibility for raising her child; her marriage dissolved. Wiseman’s daughter, Tamara Stone, has said that her mother tried to assume “the role of perfect housewife-mother” and, she might have added, daughter. As a footnote, Stone adds that her mother faced “the most dreadful blatant sexual and age discrimination” in the Canadian academic and literary communities. Her life illustrates the conflicts and challenges faced by many Jewish women in recent decades.

LOOKING AHEAD

The first Jewish woman in Canada arrived with her womanhood and her Jewishness concealed. Since then, Canadian-Jewish women have lived increasingly open lives. Like women in many countries, however, and especially in Canada where members of ethnic and religious communities and women were encouraged to stay within their own group, willy-nilly women have historically directed their energies inward towards the Jewish community and their families.

A primary concern of Canadians for much of their history was preserving their connection to Europe while grasping some of the opportunities for creativity and renewal offered by the North American frontier. Since the mid-twentieth century, Canada has become ever more democratic, egalitarian and open. The clear lines demarcating the tiles of the Canadian social mosaic have blurred somewhat. Like women and men from most groups in Canada, Jewish women are now participating widely in what were once groups or activities reserved exclusively for Jewish men or for gentiles. Ultra-Orthodox Jews, both men and women, still succeed very well in isolating themselves from the mainstreams of Canadian and Canadian-Jewish life, preserving their traditional ways. But even they are not unaffected by developments in the larger society, such as the recent changes to the Canada Divorce Act.

The positive aspect of the Canadian mosaic has been a strong Jewish community (and other communities) which nurtured traditional ethnic and religious values and benefited from the talent and energy of women and men restrained from participation in the broader society. The negative aspect has included considerable antisemitism and, especially for women, the sometimes stifling narrowness and conservatism of the community which inhibited creative and exceptional people from charting their own individual paths. The extraordinary and unprecedented achievements of individual Canadian-Jewish women at the turn of the millennium serve as testimonials to their talents and hard work, but they are also testimonials to the suppression of such talent in earlier periods. Unquestionably, individual women and men have benefited from the openness of the present day. The group, too, has benefited from the decrease in prejudice towards Jews and women and the fructification that can come from interaction in a diverse society. On the other hand, the group survival of Jews and other ethnic and religious groups is harder to ensure in the melting-pot society than it was behind the borders of a mosaic tile.

The future, of course, is impossible to predict. The extensive integration that has taken place since the 1970s has liberated individual Canadians. It threatens the former mosaic model of the polity and society of Canada, however, even as vigorous single-gender and single-ethnicity groups like those of Jewish women and of vibrant ethnic and religious communities breathe continuing life into it by maintaining their separate institutions.

The first Jewish woman to set foot on Canadian soil was expelled from the colony as an outlaw, because Jews were forbidden to settle in French colonies. Now a Jewish woman sits on the Supreme Court of Canada and another is lieutenant governor of a Canadian province. Perhaps it is not inconceivable that Canada’s traditions of conservatism and moderation will make it possible for both groups and individuals to thrive in the future in mutual enrichment. As the career of Adele Wiseman suggests, however, there is likely to be ongoing tension.

Abella, Irving. A Coat of Many Colours. Toronto: 1999.

Abella, Irving, and Harold Troper. None Is Too Many: Canada and the Jews of Europe, 1933–1948. Toronto: 1982.

Allied Jewish Community Services, Community Planning Department. Montreal Jewish Community: Attitudes, Beliefs and Behaviors. 1991, 14–15.

Arlosoroff, Chaim. Kitvei Hayyim Arlosoroff 6 (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: 1934. 198–200.

Brown, Michael. “A Case of Limited Vision: Jabotinsky on Canada and the United States.” Canadian Jewish Studies 1 (1993): 1–25.

Idem. Jew or Juif? Jews, French Canadians, and Anglo-Canadians, 1759–1914. Philadelphia: 1987.

Idem. “Canada and the Holy Land: Some North American Similarities and Differences.” In With Eyes Toward Zion III: Western Societies and the Holy Land, edited by Moshe Davis and Yehoshua Ben-Arieh, 77–91. New York: 1991.

Canadian Jewish Population Studies: Canadian Jewish Communities Series 7. Montreal: n.d..

Canadian Jewish Year Book 2 (1940–1941).

Daddy’s Gone: A Study of Jewish Single Mothers in Toronto. Toronto: 1988.

Eisen, Wendy. Count Us In: The Struggle to Free Soviet Jews—A Canadian Perspective. Toronto: 1995.

Hart, Arthur Daniel, ed. The Jew in Canada. Toronto and Montreal: 1926.

Gelber, Sylva M. No Balm in Gilead: A Personal Retrospective of Mandate Days in Palestine. Ottawa: 1989.

Land of Promise: The Jewish Experience in Southern Alberta, 1889–1945. Calgary: 1996.

Joseph, Norma Baumel. “Jewish Women in Canada: An Evolving Role.” In From Immigration to Integration: The Canadian Jewish Experience: A Millennium Edition, edited by Ruth Klein and Frank Dimant. Toronto: 2001.

Leonoff, Cyril Edel. Pioneers, Pedlars and Prayer Shawls. Victoria, British Columbia: 1978.

Lyons Bar David, Molly. My Promised Land: The Story of a Jerusalem Housewife. New York: 1953, 297.

Macleod, Roderick, and Mary Anne Poutanen. “Upstairs for Hebrew, Downstairs for English: The Jewish Community of Ste-Sophie, Quebec and Strategies for Public Education, 1914–1952,” Canadian Jewish Studies 10 (2002): 41.

Medjuck, Sheva. “If I Cannot Dance to It, It’s Not My Revolution: Jewish Feminism in Canada Today.” In The Jews in Canada, edited by Robert J. Brym, William Shaffir, and Morton Weinfeld, 328–329. Toronto: 1993.

Paris, Erna. Jews: An Account of Their Experience in Canada. Toronto: 1980.

Rosenberg, Louis. A Gazeteer of Jewish Communities in Canada Showing the Jewish Population in the Cities, Towns, and Villages in the Census Years, 1851–1951. Schlesinger, Rachel. “Changing Roles of Jewish Women.” In Canadian Jewry Today: Who’s Who in Canadian Jewry, edited by Edmond Y. Lipsitz, 60–70. Downsview: 1989.

Speisman, Stephen A. The Jews of Toronto: A History to 1937. Toronto: 1979.

Stone, Tamara. “A Memoir of My Mother.” In We Who Can Fly: Poems, Essays and Memories in Honour of Adele Wiseman, edited by Elizabeth Greene. Dunvegan, Ontario: 1997.

Troper, Harold. The Ransomed of God: The Remarkable Story of One Woman’s Role in the Rescue of Syrian Jews. Toronto: 1999.

Tulchinsky, Gerald. Taking Root: The Origins of the Canadian Jewish Community. Hanover and London: 1992.

Weinrib, Lorraine Eisenstat. “‘Do Justice to Us!’ Jews and the Constitution of Canada.” In Not Written in Stone: Jews, Constitutions, and Constitutionalism in Canada, edited by Daniel J. Elazar, Michael Brown, and Ira Robinson. Ottawa: 2003, 33–68.

Weisgal, Meyer. So Far: An Autobiography. London and Jerusalem: 1971.

Wiseman, Adele. “Word Power: Women and Prose in Canada Today.” In Memoirs of a Book-Molesting Childhood and Other Essays: Studies in Canadian Literature. Toronto: 1987.

Wisse, Ruth. Quoted in the symposium “Jewish Culture and Canadian Culture.” In The Canadian Jewish Mosaic, edited by Morton Weinfeld, William Shaffir and Irwin Cotler, 321, 323. Toronto: 1981.