Sarra Copia Sullam

Sarra Copia Sullam came from important and wealthy Venetian Jewish families. Her literary and polemical activities between 1618 and 1624 left a mark. She corresponded with monk and poet Ansaldo Cebà, and his publication of his side of the correspondence and some of her sonnets sheds much light on her personality and talent. In his published dedication of his play to her, Venetian rabbi Leon Modena recorded information about her engagement with the culture of Venice. Her published correspondence with priest, poet, and professor Baldassare Bonifaccio and her Manifesto against him on the immortality of the soul provide a further sense of her personality and education. Dramatic accounts of the plotting against her by members of her entourage, Numidio Paluzzi and Alessandro Berardelli, portray men’s reactions to an accomplished woman.

Introduction

The most well known and the least typical Jewish woman writer of early-modern Italy was Sarra Copia Sullam. The few known details of her life reveal the great opportunities and potential dangers for a woman of wealth and talent. She was born to Simone (d. 1606) and Ricca (Rivkah, d. 1642) Coppio, prominent and wealthy Venetian Jews. Her sisters appear variously as Stella (Diana or maybe Esther) and maybe Leah. She married Jacob Sullam, a Venetian Jewish communal leader and banker. Their first child died as an infant in 1615, and it does not seem that the couple had any surviving children. From around 1618 to 1624, Sarra Copia Sullam engaged publicly with leading intellectuals and produced poetry, letters, and polemics.

The Contexts: Italian Academies and Women Writers

The context of Copia Sullam’s literary activity was the academies (accademia) of the city states of early modern Italy. The most famous academy was Venice’s L’Accademia degli Incogniti (The Academy of the Unknown), formally organized around 1630 by, among others, Giovanni Francesco Loredan (1607-1661), a Venetian senator and author. Gatherings included readings of poetry, polemics, and drama; intellectual conversation and debate; and music. Members engaged in painting, circulated manuscripts, and published books. Their activities were often anonymous; conversations were conducted from behind masks; and works were published pseudonymously. They often spoke playfully, using parody, provocation, and posturing; they drew on elements of the bizarre, the grotesque, and the erotic. Almost totally male and Catholic, with libertine tendencies, the academies paradoxically fostered misogyny while enabling women writers.

In mid-sixteenth century Italy, elite secular Catholic women were emerging as poets, writers, painters, actors, composers, and singers. Women writers were praised for their talents but also served as ornaments for their families, and their accomplishments attracted both kind patronization and hostile backlash. Hence, afraid of their reputations, women might refrain from publishing their works openly, preferring pseudonyms, contributing to collected volumes, or circulating their work in manuscript or orally, often in connection with the members of the literary academies. By the end of the sixteenth century, Venice and the Veneto had become the major center for women’s writing.

Copia Sullam’s literary and academy activities took place in her house (casa), which Angelico Aprosio (1607-1681), a priest and member of the Incogniti, called an accademia. There a stream of distinguished visitors – from Treviso, Padua, Vicenza, and beyond – congregated because she was a brilliant conversationalist, though Aprosio also denigrated her originality and intelligence. Because the major episodes in Copia Sullam’s life appear in the context of academy circles, the question is whether their texts, with all their artifacts, conceits, and games, can serve as source of historical information about her life and her writing.

Corresondence with Ansaldo Cebà

In May 1618, Copia Sullam read a heroic play about the biblical Esther, L’Ester, by Ansaldo Cebà (1565-1623), a Genoese monk, author, and poet and an associate of those who would establish the Incogniti and other academies. Copia Sullam wrote Cebà of her admiration and spiritual love for him, telling him she carried his book with her and slept with it under her pillow. Cebà replied that he wished to continue to correspond with her and to convert her to Christianity. Although Cebà was a monastic and she was married, their correspondence continued, becoming more literary and polemical as well as titillating, typical of writing by members of academies. Although Cebà was a monastic and she was married, he wrote to her that like the two p’s in her name, Coppio, which means “couple,” they could be a Christian couple together. Copia Sullam immediately removed one p from her name, spelling it henceforth as Copia, now following the practice of using the female form of her family name.

They never met, but through emissaries and by mail, they exchanged pictures, sonnets, and gifts, and in 1619 she performed a musical rendition of a passage from L’Ester for one of his visiting servants. Cebà’s letters and other evidence indicate that Copia Sullam held gatherings, which included discussions of philosophy, theology, art, and literature, attended by members of academies, patricians, and government officials as well as at least one rabbi.

Copia Sullam enthusiastically discussed Cebà’s L’Ester with Leon Modena (1571-1648), a Venetian rabbi and author. In 1619, Modena published his own play about Esther that he dedicated to Copia Sullam. In his dedication, he praised her for being his patroness, for her genteel conversation, for her advanced level of knowledge for her age and sex, and especially for her interest, understanding, and writing of Italian poetry. Modena’s play was published by Giacomo Sarzina, the publisher of many books by members of the Incogniti.

The extreme expressions of love, jealously, and religious polemic in the correspondence between Cebà and Copia Sullam were part of a public performance. Each shared the letters widely, raising the esteem of both in literary circles. The drama continued after Cebà died, when a published version of his letters to Copia Sullam appeared in Genoa, edited by Marcantonio Doria. It did not include her letters, but only references to them in his own letters. Copia Sullam knew in advance that the work was in preparation, and all she asked was that one of his letters not be published in it. This request raises the questions of whether her side of the correspondence was omitted because an exposé of the thoughts she expressed might have posed some danger to her or to him (his own L’Ester was put on the Church’s Index of Prohibited Books), whether she was modest about appearing in print, or whether men felt the need to silence her voice, at least in prose, because the book does contain four of her sonnets.

Baldassare Bonifaccio and the Immortality of the Soul

At around the same time, Baldassare Bonifaccio (1585-1659) was drawn into Copia Sullam’s academy. He was a priest, archdeacon of Treviso, a prolific poet and author, instructor of law, and a member of at least five academies, including the Incogniti. To give a sense of the gatherings Copia Sullam held at her home and the connections among her associates, at one she displayed a portrait of Cebà, and Bonifaccio recited some sonnets that he wrote in honor of Cebà. Also present at this gathering was Numidio Paluzzi (1567–1625), a Roman writer and poet who was supported by Copia Sullam and served as her teacher. He was accompanied by Alessandro Berardelli, a painter, poet, and member of the Incogniti.

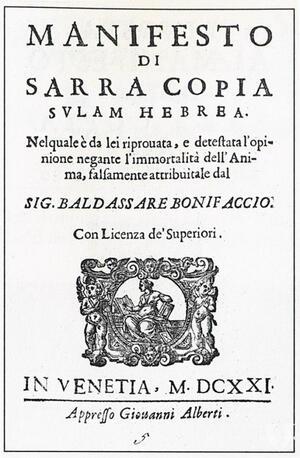

Copia Sullam and Bonifaccio discussed in person and by mail the immortality of the soul, a view considered basic to Judaism and to Christianity and a major topic for members of academies. In June 1621, Bonifacio published Dell’ Immortalità dell’anima : Discorso (On the Immortality of the Soul: A discourse). He began by saying “nor do I refuse to learn from a woman, for in intellectuals there is no distinction of sexes,” but he then accused Copia Sullam of being more dangerous than Eve listening to the serpent, the reason for the bodily death of humans. In his Discorso, he claimed that she did not believe in the immortality of the soul. Using her as a foil, he drew on passages from the Bible and Plato to formulate syllogisms to justify the dogma. Ultimately, he suggested, the issue could be resolved by her abandoning the despised condition of the Jews and becoming a Christian.

In two days, Copia Sullam wrote a Manifesto against Bonifaccio’s accusations. She began by acknowledging that her fame extended beyond Venice, that this was her first publication, that it was an area in which she was not expert, that she was recovering from a serious illness, and that she wanted to publish this work quickly. She affirmed belief in the immortality of the soul, dismissed his need to have written the Discorso, and attacked his methods and motivations, especially since she felt that their previous discussions had been intellectual exercises. In her Manifesto, Copia Sullam displayed her anger, pain, and humor as she launched into a series of ad hominem attacks and condescending remarks. She felt that his Discorso was a hostile breach of their friendship and a vain attempt to make a show of learning in which he was not competent, especially by challenging a woman. She drew on classical and Jewish knowledge, including references to the Old and New Testaments, Josephus, Aristotle, and Dante, as well as conversations that she had had with others. She also included four of her sonnets.

Bonifacio wrote a brief rebuttal, in which he denigrated Copia Sullam for excessive emotion and anger. He did not respond to the substance of her arguments because he did not think that she was able to reply and because he thought that engaging in a literary duel with a woman and a Jew would be to his discredit as a priest. He hoped that their friendship would continue, although he wrote that she was a Jezebel and a simple-minded woman. He asserted that the architect of her initial letter to him and of her Manifesto was her unnamed teacher, a rabbi, whom he admired, whose writing he recognized, and who was in debt to his family. Elsewhere, he specifically named Rabbi Leon Modena as one of those who helped with her writing. In Aprosio’s account, however, he accused Paluzzi of writing the Manifesto.

Copia Sullam had already sent Cebà a copy of Bonifaccio’s Discorso. He tried to dissuade her from responding to it and instead to focus on conversion, and he urged her not to engage in “waging war against men.” She then sent her Manifesto to him, and he replied that the way to attain immortality of the soul was to convert to Christianity.

Palluzzi and Berardelli

Numidio Paluzzi and Alessandro Berardelli had been present at academy gatherings at Copia Sullam’s house, and in exchange for her financial support Puluzzi served as her teacher. From around 1624-1625, Paluzzi and Berardelli might have been engaged in some domestic plots, literary controversies, and public humiliations involving Copia Sullam. The exact contours of these events are preserved in several overlapping, conflicting, if not imaginary, accounts. It is tempting to try to search for a grain of historical truth in these accounts, but they may reveal more about the nature of the literary interactions among the members of the academies of early modern Italy than about specific details in Copia Sullam’s life.

The fullest version of the drama is found in an anonymous Italian manuscript from about 1626. This text has two names: Codice di Giulia Solinga, after an otherwise unknown woman who wrote the dedication, the forward, and some poetry and edited it, or Avvisis di Parnaso, a literary genre developed in Italy at the end of the sixteenth century involving an imaginary trial on Mount Parnassus before Apollo. This particular trial has all the aspects of dramas of the academies, especially since it included mythical characters; classical, medieval, and Renaissance writers; Paluzzi himself, who was no longer alive; and many academy members. This literary creation contains conflicting versions of events that are also mentioned in other works associated with Copia Sullam: Cebà’s Lettere, Bonifaccio’s Discorso, Berardelli’s posthumous edition of Paluzzi’s Rime, and Aprosio’s account, which makes it even more difficult to ascertain the nature of actual events.

The manuscript described two major plots: In the first, Paluzzi, Berardelli, and members of Copia Sullam’s household staff invented an imaginary French admirer who had heard about Copia Sullam and her magic and wanted to correspond with her. In 1624, the conspirators concocted letters from this imaginary admirer that elicited from Copia Sullam costly gifts with which they absconded. When she learned the truth, she dismissed Paluzzi and Berardelli and had them charged before the Signori di Notte al Criminal; the records of this case have not yet been located.

In the second major plot, in retaliation for their dismissal, Paluzzi and Berardelli accused Copia Sullam of having received help in her writing, a charge that had already come up in Bonifaccio’s accusations against her. First, they wrote Le Satire Sarreidi, a no longer extant pamphlet slandering her. In a posthumous collection of Paluzzi’s poetry, Rime, the editor, Berardelli, reported that Paluzzi had written several works for Copia Sullam, including two books of paradoxes in praise of women against men, letters, and a manifesto on the immortality of the soul, and that while Paluzzi was sick she had taken the best part of Paluzzi’s work.

At the imaginary trial on Mount Parnassus before Apollo described in the 1626 manuscript, Paluzzi defended himself by accusing Berardelli of altering his Rime by adding accusations of plagiarism against Copia Sullam and by erasing his dedications of poems to her. What emerges is a circle of recriminations, almost a parlor game.

This imaginary trial before Parnassus, longwinded and repetitious in the spirit of writing by members of academies, was conducted by women from the past. Paluzzi was interrogated by Isabella Andreini (1562-1604), actress, writer, singer, musician, and member of the Accademia degli Intenti of Pavia (Academy of the Focused Ones). The investigating judges were some of the greatest published women writers of Italy: Veronica Gambara of Correggio (1485–1559) and Vittoria Colonna (1492–1547). They were assisted by two women writers from ancient Greece, Sappho of Lesbos and Corinna. The chief prosecutors of Paluzzi were Pietro Aretino (1492–1556) and Baldassar Castiglione (1478–1529), male authors with much negative to say about the role of women in Renaissance society. Aretino’s denunciations at the trial had all the components of writing by members of academies: bizarre, grotesque, exaggerated, and scatological, dwelling on Paluzzi’s syphilis and the prospect of his being hanged, overlooking the fact that not only was he already dead but that the trial was merely about theft and plagiarism. Cino da Pistoia (1270-1336), who had connections with Dante, Petrarch, and the Medici, appealed for mercy for Paluzzi and placed the blame instead on Berardelli.

The verdict of the judges was equally exaggerated and grotesque. Paluzzi’s punishments included the pillory, but no amputations; his forehead was to be branded; he had to wear bells under his knees; and on the Sabbath he had to stand by the door of the Temple of the Graces holding a candle. Bizarre statues of Beradelli and other members of the household were to be dragged through the streets of Parnassus, hung, and dismembered. The next day the judges held a masked banquet with singing and dancing for 500 people including mythic, ancient, medieval, and Renaissance characters, but there is no mention of Copia Sullam. Nothing further is known about her life. Her ornate tombstone in the Jewish cemetery on the Lido indicates that she died in 1641. The text of the trial of those who slandered Copia Sullam presents her among distinguished women writers and created for her a distinguished panel of defenders. Her Jewishness was noted regularly in their defense, but it certainly was not portrayed as an obstacle to her receiving a fair hearing before Apollo.

Conclusion

A full appreciation of the context of Copia Sullam’s life and work can be seen from a comparison with her Venetian Catholic contemporary, the nun Arcangela Tarabotti (1604-1652), the details of whose life – embedded primarily in literary works, sometimes using pseudonyms and elements of play and satire – can be equally obscure. Tarabotti corresponded with Giovanni Francesco Loredon, who established the Incogniti. He helped her to acquire books and to publish her work. She also corresponded with Angelico Aprosio, who also conveyed an account of Copia Sullam’s life and accusations of her plagiarism. Tarabotti had to live in forced confinement in a monastery due to family financial circumstances, and she wrote against this common practice. In 1638, in response to an attack on the vanity of women, she published an anonymous counterattack, Antisatira, against men. As Aprosio had accused Copia Sullam of plagiarism, he made a similar accusation against Tarabotti. Others claimed that a man must have written the polemic because a woman could not possibly write so well. Sheltered from society, these two women established circles that extended beyond their living quarters, to the literary academies of Venice and to an international network. Along the way, they received much recognition for their talents and support from men, but these men turned against them, accusing them of not being capable of their accomplishments and having to rely on men to do their writing for them.

Tarabotti’s and Copia Sullam’s literary careers were conspicuous for women confined in a monestary or in a Jewish ghetto. They were both well known, well connected, and isolated. However, the home and the convent were not closed, and many, especially members of academies, met with them and they were able to establish extensive networks beyond Venice. They were regularly mentioned in the literary accounts of other writers of their day, but during subsequent centuries their work appeared only in a few anthologies and bibliographies. Their public presence was both welcomed and scorned, and part of their legacy is not only their creativity and engagement but also their bravery.

Adelman, Howard Tzvi. Women and Jewish Marriage Negotiations in Early Modern Italy: For Money and Love. New York: Routledge, 2018

Adelman, Howard Tzvi. “The Literacy of Jewish Women in Early Modern Italy,” in Women’s Education in Early Modern Europe: A History, 1500–1800. Whitehead, Barbara J., ed. New York, 1999: 133–158.

Adelman, Howard Tzvi. “Jewish Women and Family Life, Inside and Outside the Ghetto.” In The Jews of Early Modern Venice, edited by Robert C. Davis and Benjamin Ravid, 143–165. Baltimore: 2001.

Boccato, Carla. “Sara Copia Sullam: La poetessa del ghetto di Venezia: episodi sua vita in un manoscritto del secolo xvii.” Italia 6 (1987): 104–218.

Boccato, Carla. “Un episodil della vita di Sara Copia Sullam: Il Manifesto sull’Immortalita` dell’Anima.” 39 (1973): 633–646.

Boccato, Carla. “Lettere di Ansaldo Cebà, genovese, a Sara Copia Sullam, poetessa del Ghetto di Venezia.” 40 (1974): 169–191.

Boccato, Carla. “Un altro documento inedito su Sara Copia Sullam: il ‘Codice de Giulia Soliga.’” 40 (1974): 303–316.

Boccato, Carla. “Nuove testimonianze su Sara Copia Sullam.” 46 (1980): 272–287.

Boccato, Carla. “Il presunto ritratto di Sara Copia Sullam.” 52 (1986): 191–204.

Boccato, Carla. “Una disputa secentesca sull’immortalità ell’anima, contributi di’archivio.” 54 (1988): 593–606.

Boccato, Carla. “Le Rime postume di Numidio Paluzzi: un contributo alla lirica barocca a Venezia new primo Seicento. Lettere italiane 57 (2005): 112-131.

Bonifaccio, Baldassare. Dell’Immortalita dell’Anima: Discorso. Venice: Antonio Pinelli, 1621.

Cebà, Ansaldo. Lettere d’Ansaldo Cebà scritte a Sara Copia, edited by Marcantonio Doria. Genoa: Giuseppe Palvoni, 1623.

Copia Sullam, Sarra. Sonetti editi e inediti raccolti e pubblicati insieme ad alquanti cenni biografici, edited by Leonello Modona. Bologna: Società Tipografica, 1887.

Copia Sullam, Sarra. Jewish Poet and Intellectual in Seventeenth Century Venice, edited and translated by Don Harran. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Copia, Sullam, Sarra. Manifesto di Sarra Copia Sulam hebrea Nel quale e` da lei riprovate, e detestata l’opinione negante l’Immortalità dell’Anima, falsemente attribuitale da SIG. BALDASSARE BONIFACIO. Venice: 1621, published in three editions.

Cox, Virginia. Women’s Writing in Italy, 1400-1650. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press), 2008.

da Fonseca-Wollheim, Corinna. “Faith and Fame in the Life and Works of the Venetian Jewish Poet Sara Copia Sullam (1592?–1641): Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Faculty of Modern and Medieval Languages, Cambridge University, 1999.

Fortis, Umberto. La “Bella Ebrea.” Sara Copio Sullam poetessa nel ghetto di Venezia del ‘600. Turin: Silvio Zamorani Editore, 2003.

Paluzzi, Numidio. Rime. Venice: Ciotti, 1626.

Reale Simioli, Carmela. “Tracce di letteratura ligure (1617–1650) nelle carte napoletane dell’Archivhio Dorio d’Angri.” Accademie e biblioteche d’Italia 49 (1981): 321–339.

Westwater, Lynn Lara. “The Disquieting Voice: Women’s Writing and Anti-Feminism in Seventeenth-Century Venice: Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Department of Romance Languages and Literatures at the University of Chicago, 2003. Westwater’s third chapter and appendix offer a significant historical study and detailed analysis of Copia Sullam’s work from a literary point of view.

Westwater, Lynn Lara. Sarra Copia Sulam: A Jewish Salonnière and the Press in Counter-Reformation Venice. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2020

Zinano, Gabriel. Rime diverse. Venezia: 1627. Contains one of her sonnets.