Benvenida Abravanel

The introduction to Solomon ben Shem Tov Atiah’s Sefer Tehilim, a commentary on Psalms (Venice, 1549, f. 1a), in which he describes the leading rabbis, kabbalists, communal leaders, and business people he met in his travels in the Ottoman Empire and the Italian Peninsula, including Benvenida Abravanel.

Benvenida Abravanel was a member of one of the richest and most powerful Iberian refugee families in Italy. Successful in business with her husband and after his death, she devoted her assets and energy to supporting Jewish causes, including the messianic movement of David Hareuveni, and maintaining Jewish culture, including supporting authors, institutions, and publications. At the same time her family did battle over her late husband’s estate in a case that left a vast and informative historical record, although she herself left very few of her own words for posterity.

Benvenida Abravanel (also known as Benvegnita, Venida, and Doña Venida) was one of the most influential and wealthiest Jewish women in early modern Italy. Her family life, however, was wracked by strife. The sources about her include literary praise of her and her family, references to her in the travel diary of the political agitator and messianic figure David Hareuveni (1490-1535/1541), rabbinic discussions about her husband Samuel’s will, in which he made her the main beneficiary and executrix, and archival materials, not all of which have yet been studied.

Family

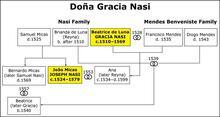

The year and the specific place in Spain of Benvenida’s birth remain uncertain. She was the daughter of Jacob Abravanel (d. 1528), a brother of Don Isaac Abravanel (1437–1508), the Spanish Jewish exegete, philosopher, and statesman. Don Isaac had three sons, the youngest of whom, Samuel (1473–1547), married Benvenida, though it is not clear where or when. With a very large dowry, she married her first cousin and was both the niece and the daughter-in-law of Don Isaacl. After waves of conversions and the establishment of the Spanish Inquisition, the Abravanels, along with the remaining Jews, were expelled from Spain. Perhaps after a stop in Portugal, where the Jews were forcibly converted in 1497, Benvenida and much of the family settled in Naples. Although Naples was under Spanish rule, many Jews and relapsed converts were able to find refugee there. First her father and then her husband, became the leaders of the Jewish community. Her uncle, Don Isaac, served in the royal court of Naples.

Benvenida had at least two sons and two daughters, and possibly one more child. She also raised an illegitimate son of Samuel’s. Depending on the source, the boys were variously called Jacob, Judah (Leone), and Isaac (Rafanellum or Benjamin), who is usually identified as the illegitimate son. The girls were Gioia and Letizia. In David Hareuveni’s description of his trip to Portugal, he wrote that Benvenida had a daughter in Lisbon who fasted every day and that her daughter’s children fasted on Mondays and Thursdays. Hareuveni found it difficult to put into words how venerable Benvenida’s daughter was, emphasizing that she was engaged in charitable and righteous deeds. Her fasting and her residence in Portugal after the forced conversions of 1497 indicate that this unnamed daughter was a penitent crypto-Jew.

Piety, Pedagogy, Politics

Benvenida’s pious activities became known around the world. When Hareuveni was in Alexandria and Jerusalem in 1523, he heard that she fasted every day, ransomed at least 1000 captives, and was known for her charitable generosity towards all who sought her aid. In 1524, she became an enthusiastic supporter of Hareuveni, although it is not clear if they ever met, and she sent him money three times when he was in Rome. She also sent him an ancient silk banner with the ten commandments embroidered in gold on both sides and a Turkish gown of gold, which she asked him to wear for her sake, highlighting her desire to support his political activities and messianic movement.

Don Pedro de Toledo, the Viceroy of Spain in Naples from 1532 to 1552, had his daughter Eleonora (Leonora) de Toledo (1522–1562) raised in Benvenida’s house. Later in life, Eleonora honored Benvenida and called her “mother.” Nevertheless, despite all the reports available in primary sources about the relationship between Benvenida and Eleonora, several writers seem to have been unable to accept Benvenida’s role as a teacher, and instead give credit to her husband.

In 1533, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V ordered the expulsion of the Jews of Naples, but it was postponed for ten years due both to the intervention of Benvenida and several princesses from Naples who petitioned the emperor, and to a significant payment to the government by the Jewish community. Although Benvenida’s young charge, Eleonora de Toledo, was only eleven at the time, she may have been one of those involved in this appeal, especially considering that her father argued against the expulsion in order to maintain the continued presence of the Jews in Naples for economic reasons. Finally, in 1541, the Abravanel family left Naples. In January, they accepted the invitation of Ercole II, Duke of Este-Ferrara (1508–1559), and headed for Ferrara, a major refuge for Sephardic Jews and former New Christians who returned to Judaism, but first they spent about a year and a half in Venice. When they arrived in Ferrara in 1543, the ducal secretary referred to Samuel as the king of the Jews from Naples.

Benvenida was engaged in the family banking business. Her former pupil, Eleonora de Toledo, had become Duchess of Tuscany and lived in Florence, the wife of the Grand Duke Cosimo Medici (1519–1574). In 1544, Benvenida went to Florence for a visit to the duke and duchess, during which they had conversations regarding religious matters. By 1547, Benvenida received permission from the authorities in Florence to open five banking establishments in Tuscany with her sons, Jacob and Judah, and despite competition from other Jewish families, she continued to expand the family’s business activities on the Italian peninsula. In 1548, the former New Christian, businesswoman, and benefactor for Jews around the world, Doña Gracia Nasi (1510-1569), received a safe-conduct to settle in Ferrara, where Benvenida was the major force in the Jewish community, and the financial interests of the two families did not always coincide.

The Contested Will

When the Abravanels left Naples in 1541, Samuel, fearing bandits and murderers because of the influx of wealthy Jews on the roads, turned to the city scribe and judge and nine witnesses to make his last will and testament, a common practice that allowed men to leave property to their wives and daughters, rather than relying on the traditional male lines of inheritance Several rabbinic [encyclopedia_glossary_term:386responsa[/encyclopedia_glossary_term] deal with the controversy over the nature of his deposition and the validity of the document.

According to the will, Samuel made Benvenida beneficiary to all his movable and immovable property because she brought a large dowry that was the source of much of their wealth, she cared for the household according to his wishes, and she showed good judgment and strong character in managing his affairs. He was concerned that one of his sons, who behaved haughtily and immorally, might destroy in a moment everything he had acquired.

Benvenida was authorized by Samuel to do what she wished with the property, except for specific amounts that he stipulated as gifts for various children when they married, provided they did so according to her wishes. In addition to sums of money provided for each child, gifts to the eldest son included a large basin, a silver jar, jewelry with a large sapphire and a ruby, a ring with a platform of diamonds, and all the parchment books that had been his father’s. He noted that Benvenida would know which books these were.

Samuel also left his illegitimate son a certain sum and made him a beneficiary, with provisions of food, drink, shoes, and clothing. When he married—if he did so according to Benvenida’s wishes—he would be given a further amount, double that which he had already received, two full beds, and more jewelry and clothing for his wife. If the will was challenged by any of the children, it would become invalid.

In 1547, Samuel died suddenly in Ferrara as a result of a drug that left him paralyzed. After waiting three years, Benvenida made public Samuel’s 1541 will. The reasons for her delay, she explained, were to protect the reputation of her husband, to protect the feelings of the sons who were disinherited, and to avoid a controversy.

“Benjamin”(Isaac), the son born outside the marriage, then demanded that the will be cancelled, asserting that a wife cannot be a beneficiary. From 1550 to 1551, Benvenida’s rights in the will became a major global dispute among rabbis from Italy to the Ottoman Empire.. Jacob and Judah sought rabbinic support against Isaac’s claims. Benvenida herself—in one of the few statements attributed to her—responded that, although according to Jewish law a wife cannot inherit from her husband, she can acquire his possessions according to the law of gifts, especially when the gift was made by a man who mentioned the possibility of his death in his bequest. She further defended her role as beneficiary on the grounds that documents produced by Jews with Christian notaries were binding, since “the law of the land” is binding on Jews.

The struggle among the Abravanels continued. Isaac seized Samuel’s account book in order to use the information in it to force Benvenida and the others to compromise with him over the terms of the will. In June 1551, he complained before a notary in Ferrara about the differences between his fortunes and those of the other members of the family: while Benvenida and the other sons had honor, wealth, and control of the estate, he was spending his portion on legal fees. He referred to himself as poor and willing to compromise.

Further Family Quarrels

Another quarrel broke out between Benvenida and the children in May 1552. She and Jacob had Judah jailed and his possessions seized because he had married a Portuguese Jewish woman in Pesaro. Although Benvenida herself had a daughter living in Portugal, her displeasure may have resulted from the woman’s crypto-Jewish past or from the rivalry between her interests in Ancona and the woman’s connection with Pesaro. On February 17, 1553, when she made her own will, Benvenida took the matter one step further by cutting Judah off completely because of this marriage and because of his involvement with Isaac’s claim to be an Abravanel in the dispute over their father’s will. Nevertheless, on June 21, 1554, when representatives of the Jewish communities of northern Italy issued a series of important enactments, at least one manuscript version of the enactments includes Isaac Abravanel among the fourteen who signed it, a possible indication of his status among the Jews of Italy despite his strained relations with Benvenida.

Additional Vulnerabilities

Showing the continued vulnerability of the family, in 1553 Jacob and Isaac handed over their copies of the [encyclopedia_glossary_term:416]Talmud[/encyclopedia_glossary_term] to the Ferrara Inquisition. In 1555, the papal inquisition immolated about 25 Iberian New Christians in Ancona. In retaliation, Doña Gracia tried to organize a boycott of the city and divert Ottoman merchants to Pesaro. Now the rivalry between the two families became especially pronounced. Unlike Dona Gracia, the interests of the Abravanel family, and especially of Benvenida’s son Jacob, were with maintaining the viability of Ancona, though his brother Judah sided with the interests of the Jews of Pesaro, where he was living with his Portuguese Jewish wife, alienated from his mother in Ferrara.

In 1563, Judah and his wife Gioia, both of whom had been accused of some sort of unspecified religious relapse, received a letter of protection from Duke Cosimo.

Recent findings indicate that Benvenida Abravanel was still alive during the 1560s.

Conclusion

Benvenida Abravanel used her family’s wealth to serve her own interests, those of her family, and those of her people. She gave generously but also reacted vindictively when she felt that her honor, influence, or assets were threatened. Married to one of the most powerful Jews of the period, she provided the source of much of his wealth and endured the humiliation of the antics of his illegitimate son as well as of some of her own children. She ultimately used her authority to punish severely those sons who did not meet her expectations.

During the sixteenth century, elite Italian women entered literary circles by supporting authors, institutions, and publications. To encourage patronage, authors dedicated books to prominent women. Benvenida received praise from Jewish writers in their books. Although these glowing dedications and comments were prompted by the possibility of financial patronage from Benvendia for the author, they indicate her involvement in a network of literary creativity. However, Benvenida herself left very few words in the historical record. In addition to her defense of women receiving bequests, one folk remedy in her name is found in a British Library manuscript. Future archival findings may enable her to speak again.

Adelman, Howard Tzvi. Women and Jewish Marriage Negotiations in Early Modern Italy: For Money and Love. New York: Routledge, 2018.

Griffi, Filena Patroni. “Documenti inediti sulle attività econimiche degli Abravanel in Italia Meridionale (1492-1543).” La Rassegna Mensile di Israel 58:2 (1997): 27-38.

Malkiel, David. “Jews and Wills in Renaissance Italy: A Case Study in the Jewish-Christian Cultural Encounter.” Italia 12 (1996): 7-69.

Segre, Renata. “Sephardic Refugees in Ferrara: Two Notable Families.” In Crisis and Creativity in the Sephardic World, 1391-1649, edited by Benjamin R. Gampel. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997, pp. 164-185, 327-336.

Samples of recent discoveries from the Medici Granducal Archive (Archivio di State di Firenze, Mediceo del Principato, 1171, f. 226r; 219; f. 35r-v) are available with translations and commentaries at http://www.medici.org/jewish-history.

Contemporaneous Praise

Atiah, Ssolomon ben Shem Tov. Sefer Tehilim. Venice. 1549, 1a

Aboab, Immanuel. Nomologia. In-Be-Ma’avak al erkah shel torah. Translated by M[oshe] Moises Orfali. Jerusalem: 1997, 266.

Hareuveni, David. Sippur David Reuveni. Edited by Aaron Ze’ev Aescoly. Jerusalem: Ha-hevrah ha-eretz yisraelit le-historia, 1940, 57, 82.

Melli, Eliezer. Le-Khol Hefez. . Venice: Daniel [Bomberg], 1552, 1a.

Sommo, Judah. “Magen Nashim.” In Zahot bedihuta de-kiddushin.Edited by Hayyim Shirmann,. Jerusalem: 1965, 138–141.

Usque, Samuel. Consolation for the Tribulations of Israel. Translated by Martin A. Cohen. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1964, 209–210.