Entrepreneurs: From Antiquity Through the Early Modern Period

Jewish women have been recorded in entrepreneurial roles as early as the fifth century BCE, and until around the nineteenth century, many women held vital roles in their communities’ economies. From the Middle East to Northern, Southern and Western Europe and the Americas, Jewish women took part in moneylending, trading, and property ownership, both with their husbands and independently. In all cultures, widows often took over their husbands’ businesses, were successful, and even expanded the original enterprise. In Egypt from 900 to 1300, some women were doctors, midwives, undertakers, and textile merchants and acted as go-betweens, representing female members of the Muslim nobility. Moneylending was a continually important entrepreneurial activity for European Jewish women, and many Jewish women around the world achieved high levels of wealth and social stature.

The dictionary definition of entrepreneur is “a person who organizes and manages any enterprise, especially a business, usually with considerable initiative and risk.” Following this definition to its logical conclusion, every pre-modern woman who managed a household was an entrepreneur since the household, at least until the seventeenth (in some places until the eighteenth) century, was an economic enterprise. For the purposes of this article, however, we have limited this broad definition of entrepreneurship, concentrating on women who specialized in commerce, selling what they themselves produced or what others produced and, in later centuries, women who were actively involved in the money economy.

Historical Background

Most of the earliest records relating to Jewish women entrepreneurs provide evidence only of prosperous women. This is because deeds and ownership lists were the transactions most often recorded in ancient societies, and it is this kind of information that remains. Such documents, preserved either in stone or on papyrus, reveal women as property owners, philanthropists, and buyers and sellers of real estate or large amounts of movable goods.

There are records of women property owners as early as the fifth century BCE. One was Mibtahiah, who lived in the Jewish colony of Elephantine. She bought and sold her properties and also owned valuable goods that she disposed of independently. Later records, from rural Egypt in the second century CE, show Jewish women who owned large herds of livestock. In that same century, documents from the Cave of Letters, uncovered by archeologists in the 1960s, inform us of Babatha, a woman from Judea who owned property and lent money to her husband.

Since poorer women rarely required the use of official documents, fewer details of their economic activities have been recorded. This fact gives a skewed image to history, since most people, whether Jews or gentiles, men or women, were not large property owners and thus have left scant evidence behind. However, from the little we know, we can assume that almost all women, from the richest to the poorest, were economically active. Even women who performed the traditional female jobs of spinning, weaving, and growing and preparing food often engaged in selling the surplus and thus were entrepreneurs.

Women who hired themselves out as wet-nurses might also be considered entrepreneurial, as they performed this service in exchange for money and accepted the responsibilities and risks that went along with that work. Wet-nursing was one of the few ways poor women might earn money without an initial investment, and several extant contracts are witness to the fact that some Jewish women earned a living in this way. One such woman, Theodote of Alexandria, lived in the first century CE and contracted to suckle a slave child for eighteen months. She was to get half of her money in advance. Another contract revealed a similar agreement with a wet nurse named Marta.

Both the Codification of basic Jewish Oral Law; edited and arranged by R. Judah ha-Nasi c. 200 C.E.Mishnah and the Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmud, reflecting Jewish life styles from the first century CE to the sixth century CE, assumed that most women worked. The sages carefully explained that the proceeds of a married woman’s labor belonged to her husband unless he failed to provide for her maintenance. In that case, she was allowed to use her earnings to support herself. These were traditions that conformed closely to social usage throughout the Middle East. They also fit well with the Biblical ideal of the woman as helpmate to her husband.

As helpmate, a woman might be a busy entrepreneur; she could buy and sell the fruits of her own or other women’s labors in the marketplace, acquire estates, plant vineyards, sew garments, either for her family or for sale, and teach other women. All these activities were expected of her in her role as helpmate. In fact, long before the Mishnah and the Talmud laid out the duties of a wife, these activities were all mentioned in the Biblical book of Proverbs (31) that described a woman of valor.

In later centuries, the assumption that women would work and make their own economic contribution to the household became even more entrenched, especially in Europe. In the early tenth century, R. Meshullam ben Kalonymus of Lucca, Italy, one of the founders of the Mainz Jewish community in Rhineland, Western Germany, pointed out in a Halakhic decisions written by rabbinic authories in response to questions posed to them.responsum: “It is the custom of men to appoint their wives as masters over their possessions.” In the eleventh century R. Solomon ben Isaac (Rabbi Solomon ben Isaac; b. Troyes, France, 1040Rashi) of Troyes, France, noted that a woman could do four things at one and the same time: “Watch the vegetables, spin flax, teach a song to a woman for a fee, and warm silkworm eggs in her bosom.” (Rashi to Ket. 66a, s.v. “ve’shalosh be’arba.”) At least two of these activities were income-producing.

In Muslim society, despite the growing isolation of women from the public and working life of the community, there is much evidence that Jewish women worked, most often side by side with husbands, but sometimes also independently. This was particularly evident in medieval Egypt. While Jewish women certainly did not enjoy equality, and their professional opportunities were much narrower than those available to Jewish or other minority men, they did often function in a variety of occupations.

If the father of a bride was rich enough or influential enough, a medieval Egyptian Jewish woman’s marriage contract (Marriage document (in Aramaic) dictating husband's personal and financial obligations to his wife.ketubbah) might allow her to keep her earnings and use the money to buy her own clothes. Later, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Jewish women in Arabic-speaking areas often had a similar clause in their marriage contracts, stipulating that the profit of a wife’s labor belonged to her and was not the property of her husband. This was one of the factors encouraging substantial commercial activities among the Musta’rab, indigenous, Arabic-speaking Jewish women. Interestingly enough, in spite of the relatively freer atmosphere for women in Europe, such a clause was never adopted in the marriage contracts of Jews in the West.

East or west, however, the women who appear most frequently in commercial records were widows. Widows often took over their husbands’ businesses, and while this was usually out of necessity, many were successful and even expanded the original enterprise. Because a woman usually received the promised payment from her ketubbah upon the death of her husband, this might give her a considerable sum of money, a lump sum never available to her while married. Many widows took the opportunity to invest this money, either by lending on interest—a common activity for women, both married and widowed—or as part of a commenda. A commenda was a type of partnership in which a person could invest as a silent partner in someone else’s business with a promise of a share in the profits. Other widows simply continued a skill that they had practiced in their husbands’ or fathers’ homes, such as embroidery, sewing, weaving, or other handicraft, and turned it into a business. Widows who failed most often became the responsibility of the Jewish community, and many appear on the charity rolls in every area of Jewish settlement.

Jewish Women Entrepreneurs in Muslim Lands

Egypt (900–1300)

From the seventh and eighth centuries on, Islamic governments ruled the Middle East, North Africa, and Spain, and the Jewish communities in those lands were heavily influenced by the Muslim attitude towards women. However, Jewish women’s freedom to engage in business activities was not always as curtailed as it would later become. While most female roles were limited to managing households and helping husbands in their work, many women did have an independent working life outside the home. Nowhere was this more documented than in Egypt, from 900 to 1300 under the Fatimid dynasty. Women in Egypt were doctors, midwives, undertakers, and textile merchants. They might also earn money as professional mourners or as bride combers. These were, in a sense, free-lance businesses. Some women worked as textile brokers, visiting the homes of other women to buy and sell their wares or trading the material in bazaars. Such activities were made easier for Egyptian women since the stipulation that women needed a male guardian when appearing in court—a requirement since Roman times—had been dropped. Women in Fatimid Egypt were allowed to appear in court on their own recognizance.

The most noted entrepreneur among the Egyptian Jewish women was Karima, the daughter of Ammar of Alexandria, a broker mostly referred to in documents by her nickname, Wuhsha. Married and divorced at least once, Wuhsha was the subject of several local scandals, but her economic success seems to have allowed her significant leeway in her social behavior.

As an active businesswoman, Wuhsha dealt with large sums and was accustomed to move around in the company of men. Several records concerning her business dealings have been preserved in the Cairo Place for storing books or ritual objects which have become unusable.Genizah (a repository for Jewish documents). In a lawsuit dated June 30, 1104, Wuhsha claimed eight hundred dinars, her share of an investment in her late brother’s commenda with two other people. Another claim shows the participation of Wuhsha in a trading venture in which twenty-two camel-loads of goods, totaling eleven thousand pounds, had already arrived at the time the court recorded her suit. Some of her holdings consisted of loans, for which she held collateral.

Wuhsha also had business dealings with women. One document shows her releasing a woman, Lady Beauty, from all obligations she might have incurred while making transactions on her (Wuhsha’s) behalf.

In over one hundred lists of donations to charitable causes, Wuhsha was the only woman whose name appears alone. In her will, in addition to dispositions to her family and the stipulation of her funeral expenses, she set aside money for the cemetery, several synagogues, and some poor people. In total, she willed about a tenth of the value of her estate to charity. Even after these deductions, Wuhsha was able to will a large estate at her death, including property, movable goods, and cash, some of it in gold. The bulk of her inheritance went to her son.

The Ottoman Empire (Fifteenth to Eighteenth Centuries)

In later centuries, there is much evidence of women’s entrepreneurial activities in the Ottoman Empire, which at one time encompassed the Middle East, Turkey, Greece , the Balkans. In the sixteenth century, at the height of Ottoman power, there were many types of work available for Jewish women. There were, of course, some limits based on what the community considered proper for their sex, but the parameters were surprisingly liberal. Moneylending was considered a desirable profession for women; widows and divorcées especially often engaged in this occupation, using their Marriage document (in Aramaic) dictating husband's personal and financial obligations to his wife.ketubbah money as an initial fund. In a query addressed to R. Eliezer ben Arha (d. 1652) the writer pointed out that in Jerusalem: “ … any man or woman who owned one hundred grushos (silver coins) could start up in the money lending business. …”

Women who had no cash assets found other ways to participate in economic life. Many owned real estate as part of their dowries and rented out space. Large numbers of women were involved in local trade, sometimes functioning as intermediaries, selling the handiwork of Muslim women. Pierre Belon, a traveler who visited Turkey in the sixteenth century, reported that “Jewish women who could go around with their faces uncovered are commonly found in the Turkish markets selling needlework. Since Islamic law does not allow Turkish women to sell and buy, they sold their [products] to Jewish women. … They [the Jewish women] ordinarily sold towels, kerchiefs, headgear, white belts, cushion covers, and other such products of much greater value … that the Jews bought to sell to strangers.”

The limitations on Muslim women created an additional opportunity for their Jewish and Christian counterparts, who were required as go-betweens, representing the female members of the Muslim nobility to the outside world. A few of the most outstanding of these were Jewish women who acquired the trust of the ladies of the Muslim Court and, functioning as their agents, built successful enterprises.

One such woman was Ester Kiera (a Greek word meaning “Lady”) Handali, who began her working life as a peddler and, together with her husband, sold trinkets and jewelry to the women of the Sultan’s harem. When she became widowed, she proved useful to the royal women by purchasing cosmetics, jewelry, and clothing for them and in general creating a link between the harem and the outside world. Through her activities she gained a great deal of political influence as well. This eventually led to resentment and finally to her execution by a mob in Istanbul in the last years of the sixteenth century.

However, Handali’s unhappy end did not eliminate this kind of work for other Jewish women. Esperanza Malchi was undoubtedly one of the successors of Ester Handali. In 1599, in a letter to Queen Elizabeth I of England, Esperanza described herself as “chief ladies’ maid” to the Sultan’s harem. She was writing to the queen on behalf of “the Serene Queen Mother” of the Ottoman Empire, who was sending expensive gifts to Queen Elizabeth. In return, Esperanza requested, on behalf of her employer, cosmetics and cloths of wool and silk from England. By providing necessary services to the harem women, Jewish women go-betweens, the kieras of the royal courts, were in a position to request and sometimes to receive important concessions.

But Jewish women who worked as agents for others made up only a small part of women’s business activity. Most often, they sold their own products, dealing especially in textiles of wool, linen, and silk, or in foodstuffs such as grain, wine, olive oil, and spices. The poorest sold the products of their own kitchens or kitchen gardens: pita, yogurt, or vegetables.

Other Jewish women were artisans. They embroidered and sewed and sold their goods to contribute to the family income or, in some instances, to support themselves. Rachel Sussman, an Jews of European origin and their descendants, including most of North and South American Jewry.Ashkenazi woman living in Jerusalem in the second half of the sixteenth century, reported that her daughter-in-law Beile “embroidered very nice things from silver and gold” that could be sold in the marketplace. In Salonika, where almost all the Jews were involved in the textile industry, women were active workers, dyeing the cloth, preparing it for market and selling it.

Isolated women have also been documented in more unusual professions. A Jewish widow from Aleppo (referred to in a Halakhic decisions written by rabbinic authories in response to questions posed to them.responsum by the pseudonym Leah) was a welder. She had originally learned the trade from her husband. A few Jewish women were public criers, proclaiming what was being sold and where. We know of A’ira bint (daughter of) ‘Abd-Allah, from North Africa, who was a crier in Jerusalem in 1558, and Maryam bint Ya’qub, Hanna bint Shuba, Kalala bint Ibrahim the Maghrebi and Simha bint Yusef who did the same in 1595.

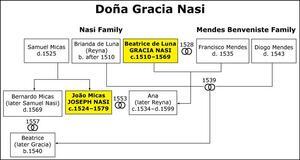

Although the vast majority of Jewish women were engaged in simple businesses, either in the marketplace or on its fringes, there were always the few who were rich and accomplished. The most outstanding of the women entrepreneurs, and the richest, both in Europe where she lived as a secret Jew, and later in the Ottoman Empire, was Beatrice de Luna, better known as Gracia Nasi, the name she adopted. Her life spanned the sixteenth century and her travels brought her from Portugal to Antwerp, then to several cities in Italy and finally to Istanbul. She controlled one of the largest fortunes in Europe and forged connections to rulers throughout the Western world.

Born into a converso family in Portugal, Beatrice married Francisco Mendes, a wealthy trader in gems and spices. Widowed in 1535, she became heir to half of the enormous Mendes fortune. At that time, she joined her brother-in-law in Antwerp and became involved in banking, which included the transmission of monies and the arrangement of bills of exchange. The Mendes firm granted credit to Italy, Hungary, and Poland. Utilizing their own ships, the firm traded in wool, linen, textiles, spices, and grain. After the death of the second Mendes brother, Gracia continued her vast business network alone, operating first from Europe as a Christian, then as a Jew from Istanbul, where she had been invited to take up residence by the Ottoman Sultan himself.

A good deal of Gracia’s fortune was spent on philanthropic works for the Jews. These included the funding of the first Spanish-language version of the Hebrew Bible, the founding of a Jewish settlement in Tiberias (Palestin,e) and the rescue of secret Jews who were threatened by the Inquisition. By the time of her death in 1569, she had achieved power, fame, and riches beyond most people’s imagination.

Jewish Women Entrepreneurs in Christian Europe

Northwestern Europe (Eleventh to Fourteenth Centuries)

Jews were originally invited into northwestern Europe (the Carolingian Empire) as merchants, to help increase the flow of goods to the West. Given that background, it is not surprising to find that several centuries later many Jews in European lands were still working as commercial traders or in occupations that furthered trade, such as lending money or acting as agents for the nobility. And because men routinely worked together with wives and children, women also followed these same professions, though with some differences.

While Jewish men traded throughout Europe and might travel far into Muslim lands, staying away for long periods of time, Jewish women traveled less and did not go as far. They could, however, act as local agents for long-distance traders who were often—but not always—their husbands. Sometimes, women earned money by supplying goods on a fixed commission, allowing the men to keep whatever excess profits they might be able to receive.

One of the earliest Jewish women entrepreneurs in northwestern Europe was Minna of Worms who lived in the Rhineland (western Germany) in the eleventh century. She lent money and was respected by both the gentile and Jewish communities. Minna was among the many Rhineland Jews who fell victim to the first Crusade of 1096.

Another woman from the late eleventh century who had economic connections with the feudal authorities is mentioned in a question sent to Rabbi Solomon ben Isaac; b. Troyes, France, 1040Rashi. Referred to by the pseudonym Leah, she held the right to collect the tithe in a certain village—a right that she had obtained from the local ruler.

In the following century, we know a little more about a woman named Dulcea of Worms, a busy entrepreneur as well as a spiritual leader to the women of her community. According to the description written after her death by her husband, R. Eleazar ben Judah of Worms (1165–1230), Dulcea spun cords for sewing the parchment of Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah scrolls, Phylacteriestefillin, and Lit. "scroll." Designation of the five scrolls of the Bible (Ruth, Song of Songs, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther). The Scroll of Esther is read on Purim from a parchment scroll.megillot. She made wicks for the synagogue and the schools and taught prayers and songs to the women in her own and in neighboring towns. But the bulk of her earnings were gained through her activities as a financial agent. Her husband wrote, “she supported me and my son and daughters by [lending] other people’s money.” Using the words of the Biblical book of Proverbs, R. Eleazar continued his praise of Dulcea, explaining: “Her husband trusts her implicitly, she fed and clothed him in dignity so he could sit among the elders of the land and provide Torah study and good deeds.”

Eleazar’s words imply that Dulcea was a helpmate to her husband not by working with him, but by working instead of him, freeing him to spend his days in study and teaching. This model eventually became the ideal in Eastern Europe, but during the Middle Ages it was far more common for European women to work side by side with their husbands. Despite this fact, most of the earliest records of women entrepreneurs relate to widows. This was because of the Talmudic ruling that a wife’s earnings did not belong to her but to her husband. Any record of a married woman’s business dealings, therefore, even if solely through her own talents and efforts, was automatically counted as part of a family income and registered to the male head of that household.

Working widows were common throughout the Middle Ages in every area of Europe. In eleventh-century France we find a widowed farmer who worked her land alone, with the help of sharecroppers. She complained about the amount of taxes she had to pay and her problems were catalogued in an appeal to Jewish communal leaders.

Pulcellina of Blois, France, a widow who was martyred with the other Jews of Blois in 1171, probably worked as a moneylender, since documents concerning her note that she was well known to the nobility and that she “acted proudly.” Earlier assumptions that she had been a lover to the Count are now being reexamined.

Women moneylenders were even better documented in England, where Jews were brought in by the Norman conquerors specifically as merchants and lenders. The royal rolls are filled with the names of Jewish women who worked in this profession, usually taking pledges for money lent.

Licoricia of Winchester was one of the most successful of these lenders. She began moneylending as a young widow in Winchester in the 1230s. By 1239 she was an active moneylender and may have continued this work during her brief second marriage, from 1242 to 1244. After the death of her second husband, David of Oxford, she was a successful moneylender for the next thirty-three years, lending money to the nobility throughout southern England, sometimes in partnership with her sons, but mostly as an independent entrepreneur. She continued her business until her murder in 1277, the result of a robbery.

Another Jewish woman moneylender in medieval England was Chera (d. 1244), prominent in Winchester. She often lent in partnership with one of her sons. Her business interests were widespread and there are records of her loans in Kent, Nottingham and Devon. A large number of her Winchester deals were with churchmen although she also lent to small landowners.

Chera’s daughter-in-law, Belia of Winchester (d. after 1273), began lending money on her own or with partners after the death of her husband, Deulebene, in 1235. Over the next few years her standing in the Winchester community grew and in 1241 she was elected to be responsible for the Winchester hostage, her brother-in-law Elias, who was answerable for collecting the community’s tallage. Belia was the only woman in medieval England elected to such a position. After her marriage to her second husband, Pictavin of Bedford, Belia moved to Bedford and became a powerful member of that community. She often appeared in court in Bedford and in Winchester, pursuing debtors, both her own and Chera’s.

In addition to Chera, Belia, and Licoricia, there were a number of other prominent women moneylenders in medieval England. These included Avigay of London; Belassez of Oxford; Belassez, widow of Leo; Bella and her granddaughter Pucell; Comitissa of Cambridge; Floria, widow of Bonevie of Newbury; Floria, widow of Master Elias; Henne, widow of Aaron of York; Henne, widow of Jacob of Oxford; Milka of Canterbury and her daughter, Mirabel of Gloucester.

In Germany, too, numbers of Jewish women, mostly widows, became successful moneylenders, especially during the fourteenth century. These include Kandlein of Regensburg, Reynette of Koblenz, and Minna of Zurich.

Kandlein of Regensburg was a widow whose family were among the largest taxpayers in their town. Not only was she a prominent moneylender, but after her husband’s death she became one of the appointed leaders of the Regensburg Jewish community, a post she held for at least two years. She was also the leader of the group that set the taxes for the Jews in the town. Along with others, Kandlein regulated which Jews should be allowed to settle in Regensburg and how much they should pay for the privilege. Although her dates of birth and death are not recorded, she was active in business until October 8, 1358, when the last mention of her name appears in town records. Later documents indicate that she was murdered and that her son took over her business.

Reynette of Koblenz became an independent entrepreneur following the death of her first husband, Leo. She continued in the moneylending business during her second marriage to Moses Bonenfant and eventually the size of her financial dealings surpassed those of both her husbands. Her most successful year was 1372, when she raised the exceptional sum of eight thousand guildens to meet the demands of the Andernacher city fathers.

Financial documents concerning the widow Minna of Zurich show her in partnership with her two sons in the fourteenth century. In all likelihood she simply continued what she had done together with her husband, Menahem of Zurich, but after his death her name appeared in the records instead of his. Theirs was one of the richest families in Zurich and Minna owned a house with a grand salon and painted murals. She was known to have raised substantial sums of money, and one of her loans had the value of eight to ten large town houses.

Besides the paucity of records concerning the activities of married women, the stipulation that they could not own or control their own earnings created another interesting result. Married women could not be held liable for any loss because technically they owned nothing. As entrepreneurial activity increased in Europe and the society became more sophisticated economically, this dilemma, long ago noted in the Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmud (B. Baba Kamma 87a), became more problematic and many sages, beginning in the eleventh century, sought solutions. However, since all of the suggestions depended on the good will of either the person who caused the loss or the one who incurred it, they never completely solved the problem.

Only in the second half of the twelfth century did R. Eliezer ben Nathan (c. 1090–c. 1170) find an acceptable, two-part compromise. The first part claimed that the right of a husband to the fruits of his wife’s labor did not relieve her of responsibility for her own actions. This part of the decision was controversial and many sages believed that it was against Jewish law. The second part was far more acceptable. It established that no matter in what activities a wife engaged, she was always acting as an agent for her husband and therefore he was always responsible for her losses. This was the case even if she administered her own business or profession independent of his supervision. R. Eliezer’s ruling was widely accepted and allowed businesses to function more smoothly, but it did little to advance a married woman’s status. Throughout the Middle Ages, and well into the early modern period, there continue to be very few documents recording the business activities of married women.

Only the rabbinic Halakhic decisions written by rabbinic authories in response to questions posed to them.responsa reflect the heavy involvement of married women in commerce. As is the case in all responsa, real names are never given, but from this vast literature we know about the business activities of many married women. One early example describes a mother and daughter who produced gold-embroidered gloves and sold them through a third party. Another describes a woman who had been in casual partnership with someone else’s husband. She gave him supplies and he, in return, gave her silk “from his assets.” One woman had an arrangement with her brother who sold products that she had made and took a commission. Sometimes women combined commercial and financial activities. A twelfth-century French woman began by trading. When she had accumulated enough capital, she went on to moneylending. R. Eliezer ben Natan, in his writing on women’s responsibility for loss, clearly affirmed the varied business activities of married women. He wrote “[W]omen work as administrators and shopkeepers. They are business women; they borrow, they lend, they pay, they collect, they take pledges and make deposits.”

Moneylending continued to be an important entrepreneurial activity for European Jewish women, especially during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, when economic activity increased. One medieval German Jewish writer noted that daughters needed to be taught reading and writing so that when they lent money they would not be forced to call in a man to record the pledge for them, since this might lead to sin.

Southern Europe

Italy, the earliest site of Jewish settlement in Europe, reveals few records of Jewish business activities until the Middle Ages, but by the late thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, we begin to find many Jewish women engaging in commerce, most working together with their husbands. Here, too, moneylending was a common occupation for Jewish women and there is a great deal of evidence of it throughout southern Europe. In thirteenth-century Perpignan (then part of Catalonia), twenty-five of a total of sixty-one loans recorded in the register were made by women. Thus, women were principals in about forty percent of the loans found in those records. The frequency is even higher in parts of southern France.

Although moneylending activities leave the most records behind, Jewish women were involved in other areas as well, especially those closely tied to women’s traditional activities—the production of food and clothing. Records of the sixteenth century show Stella Sacerdote and Chiara Sciunnach who engaged in the silk business, Dulcia bat Hanniah who raised buffalo (probably for manufacturing cheese), and Gioia di Montalto, who manufactured and sold buttons.

The making and selling of cosmetics was also an accepted profession for Italian women and several are mentioned in that field. One of these was Anna the Hebrew who supplied the Italian noblewoman Catherine Sforza with face cream and other lotions and powders. In one letter to Catherine she listed the products she manufactured along with their uses and gave a price for each one.

Venguessone Nathan, a fifteenth-century woman from a prosperous Provençal family, was both a merchant and a moneylender. She was the largest possessor of property in Arles in 1424 and owned a shop where she sold draperies and dishes of wood, earthenware, and glass. She also owned books in both Hebrew and Latin. Many of her business activities are known through her will, which listed debts and pledges as part of her assets. In addition to these as yet unpaid assets, she bequeathed to family members “a house and well free of all taxes,” “a vineyard in St. Medard,” and jewels of gold, silver, and pearls as well as items of silver plate and large amounts of cash.

Among the records concerning the Jews of Navarre, from the end of the thirteenth and first half of the fourteenth century, we find information on some Jewish women who were active in all sorts of commerce. Oro Ceti Franco was the most important merchant of thread and sold belts, turbans, dresses, shirts, linen, wool, fur, and parchment. She was also in the meat business and, together with Esther Harbon, also sold an assortment of foodstuffs. This same Esther Harbon was part of the group of Jewish silk merchants that included another woman, Esther Mayo. Donna Cedella was an important seller of belts, turbans, dresses of wool, linen, and cloth. Oro Ceti and Oro Shul assisted their husbands in the footwear industry. They exported, repaired, and marketed shoes of all kinds and had both Jews and Christians among their customers. Oro Ceti also sold accessories, while she and Esther Harbon also manufactured and sold leather and fur. Two other women, Donna Gamila, widow of Don Ismail Abad, and the widow of Isaac ibn Shaprut (it is not known whether Isaac is a descendent of the tenth century Hisdai Ibn Shaprut.), were moneylenders, also from Navarre.

Benvenida Abravanel was one of the most successful businesswomen in southern Europe, perhaps second only to Doña Gracia. Like the latter, she operated from Italy for many years. Also part of a substantial and prosperous family, Benvenida was born in Spain and migrated to Naples after the Spanish expulsion of Jews in 1492. Well educated in both Jewish and secular subjects, she began her working life as a teacher to Eleonora, the daughter of the Spanish Viceroy. Benvenida lived comfortably and was a generous philanthropist. Although she probably assisted her husband Samuel, who was a commercial trader, it was only after Samuel’s death in 1547 that she became more active commercially. Her husband left her full control of the family business, which she expanded. Working with her two sons Jacob and Judah, and possibly also with a son-in-law, she became successful in her own right, obtaining important commercial privileges through her connection with Eleanora, Duchess of Tuscany, the woman she had once tutored.

Central and Eastern Europe

When the Jews were expelled from the various territories of Western Europe, many emigrated east. Settling in eastern Germany, Bohemia, Poland, and Lithuania, they usually took up the same professions that had supported them in earlier times. Commerce and trade were needed in these developing lands and the Jews, both men and women, were experienced in that field.

In the course of business, women routinely went outside their homes to the marketplace and some traveled longer distances. They bought and sold on their own account or for a family business; they owned property in their own names and pursued a variety of activities, both inside and outside the home, in order to help make a living. In the towns and villages of Eastern Europe it became even more common for a woman to gain favor in God’s eyes by supporting her family and enabling her husband to study.

As it was everywhere, Jewish women often followed occupations that were connected to their responsibilities in the home. Records show women working in the food trades, for example as cheese-makers and goose herders, and in the clothing trades, as veil makers, weavers, embroiderers, milliners, and seamstresses. Poor Jewish women often worked as street vendors. By the sixteenth century, when Jewish life was well-established in Eastern Europe, R. Solomon ben Jehiel Luria (1510?–1574) wrote: “Our women now conduct business in the house [and] represent the husband.”

From the writings of one Jewish man from Mezhirichi, Moravia, we know that his mother Gnendel initially supported her family by making brandy in her kitchen, while her husband studied. “This was very hard labor,” he wrote, “but she succeeded.” Later, her husband joined her and the local count granted them the right to operate a distillery. This work was very difficult and the heat and fumes eventually made her sick. Gnendel died in 1672 at the age of thirty-four.

In addition to working with her husband in business, Sarel Gutman of Prague, another seventeenth-century woman, organized and ran a private mail service from Prague to Vienna. She originally started it to facilitate communication with her husband, who often traveled to Vienna on business. But the enterprise was a success and paid messengers carried letters back and forth on a regular basis.

In every location a few Jewish women stand above the rest because of their success and relative prosperity, and Eastern Europe was no exception. During the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries, many of these prosperous women were moneylenders. Approximately twenty-five percent of all moneylenders in Eastern Europe were women and some Halakhic decisions written by rabbinic authories in response to questions posed to them.responsa even indicate that married women may have worked independently of their husbands. Others had some connection with the nobility, as court factors or agents.

Court factors engaged in a type of money lending. They laid out money for members of the nobility, buying items that the court needed or the nobleman himself desired, and were paid back with interest and often with increased privileges. In the eighteenth century Blümele Homburg of Mainz (western Germany) took over her husband’s business after he died and became court factor to the ruler there, supplying his army. A woman known only as Chaile Raphael Kualla, matriarch of a large and influential family, was a court factor in Württemberg.

The best-known and most successful of the court factors was Esther Schulhoff Liebmann, who came from a distinguished and scholarly family and was first introduced to the world of business through her first husband, Israel Aron. When he died, the financial challenges she faced were daunting. She managed to extricate herself, partly through a second marriage to Jost Liebmann, to whom she offered, in lieu of a dowry, her contacts with Frederick I of Prussia and her right to dwell in Berlin. After Jost’s death in 1702 Esther continued their business, supplying precious jewels and gems to Frederick I and his family. Because the royal family owed her so much money for all the jewelry she had supplied after her husband’s death, she was given the right to mint and distribute coins. Her fortunes waned after the death of her royal patron, Frederick I, and most of the debt owed to her remained unpaid. Esther died in 1714.

Although a large number of financially successful women were engaged in the money trades, this was not always the case. Rachel (Rashka) of Poland, a sixteenth-century widow, became active in her husband’s business affairs and also in communal affairs. She was granted an honorary position in the king’s court and was the only Jew granted the right to own a house in Cracow after the expulsion of Jews from that city.

Glückel of Hameln lived most of her life in Hamburg (northern Germany) in the seventeenth century. As a young wife and mother she advised and aided her husband in his business dealings. After his death she continued his business of buying and selling and was very successful at it. As she wrote,

At that time I was still quite energetic in business, so that every month I sold goods to the value of five thousand to six thousand reichstaler. Besides this, I went twice a year to the Brunswick fair and at every fair sold goods for several thousands … I did not spare myself but traveled summer and winter and all day rushed about the town. ... I had a fine business in seed pearls. I bought from all the Jews, picked and sorted the pearls and sold them to the places where I knew they were wanted. I had large credits. When the Bourse was open and I wanted twenty thousand reichstaler, cash, I could get it.

As a young widow Glückel supported eight of her twelve children (the older ones were already married). Although she often borrowed money for her business needs and was acquainted with important Christian citizens, she did not lend on interest.

Many Jewish women were successful printers, running the active Jewish presses of Eastern Europe together with their husbands. Some, such as Gutel bat Yehudah HaKohen and Bella Hurwitz, both from Prague, and Rebecca and Rachel Judels of Wilmersdorf gained prominence as printers.

Through the nineteenth century, women in the Eastern European villages and towns continued to work alongside their husbands as shopkeepers or in small businesses and widows usually took over those businesses. This was also true for the few Jewish women who settled in the colonies of the New World. For example, Abigail Minis of Savannah, Georgia, widowed in 1756 and with eight children to support, ran the family farm and a retail business single-handedly. She was successful enough to be able to acquire additional property and she and her five daughters operated a local tavern.

Although women continued working throughout the 1800s, managing a household and caring for children was becoming more of a primary activity throughout the western world. As the nineteenth century neared its end, the Jewish middle class was embracing this new standard: Women remained at home and men supported them. As Jews trickled back to Western Europe, this practice became more and more common. In larger cities, where the industrial revolution had taken most work out of the home and into factories, women who needed to earn money increasingly looked to the fields of education and social work, while less educated women went into the factories and became wage earners. By the nineteenth century this was true in North America as well and the Jewish women who gained prominence were mostly involved in the fields of philanthropy or labor union organizing.

In the latter half of the twentieth century, Jewish women re-entered the work force in large numbers and are now reclaiming the entrepreneurial fields that they had left behind only a few centuries ago.

Agus, Irving. Urban Civilisation in Pre-Crusade Europe. 2 vols. New York: 1965.

Assis, Yom Tov, and Ramón Magdalena. The Jews of Navarre at the Close of the Middle Ages (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 1990.

Bartlet, Suzanne. “Three Jewish Businesswomen in Thirteenth-Century Winchester.” Jewish Culture and History 3 (2000): 31–54.

Baskin, Judith. “Dolce of Worms: Women Saints in Judaism.” In Women Saints in World Religions, edited by Arvind Sharma, 39–69. Albany: 2000.

Bastian, Franz and Josef Wideman (eds.). Monumenta Boica Regensburger Urkundbuch II Band Urkunden der Stadt 1351–1378. Munchen: 1956.

Breuer, Mordechai. “The Early Modern Period.” In Tradition and Enlightenment: 1600–1700. Vol. 1 of German-Jewish History in Modern Times, edited by Michael Meyer. New York: 1996.

Davis, Natalie Z. Women on the Margins: Three Seventeenth-Century Lives. Cambridge, MA and London: 1995.

Einbinder, Susan. “Pulcellina of Blois: Romantic Myths and Narrative Conventions.” Jewish History 12 (1998): 29–46.

Eliezer ben Natan. Sefer Raban (1904, reprinted in Jerusalem in 1983–1984), part 1, 115.

Emery, Richard. The Jews of Perpignan in the Thirteenth Century. New York: 1959.

Emery, Richard. “Les veuves juives de Perpignan (1317–1416).” Provence Historique 150 (1987): 559–569.

Garshowitz, Libby. “Gracia Mendes: Power, Influence, and Intrigue.” In Power of the Weak: Studies on Medieval Women, edited by Jennifer Carpenter and Sally-Beth MacLean, 94–125. Urbana & Chicago: 1995.

Glückel of Hameln. The Life of Glückel of Hameln, 1646–1742, Written by Herself. Trans. and ed. Beth Zion Abrahams. New York: 1963.

Goitein, Shelomo D. A Mediterranean Society: the Jewish Communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Genizah. 6 vols. Berkeley: 1967–1993.

Grossman, Abraham. Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Europe in the Middle Ages . Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2012.

Habermann, Abraham Meir. Women as Printers, Editors, Publishers and Financial Backers (Hebrew). Berlin: Reuben Mas, 1932–1933.

Iancu-Agou, Danièle. “Une vente de livres hébreux à Arles en 1434: Tableau de l’élite juive Arlésienne au milieu du XVe siècle.” Revue des études juives 146 (1987): 5–62.

Jordan, William Chester. “Women and Credit in the Middle Ages: Problems and Directions.” The Journal of European Economic History 17 (1988): 33–62.

Keil, Martha. “Business Success and Tax Depts: Jewish Women in Late Medieval Austrian Towns.” In Jewish Studies at the Central European University II (1999–2001), edited by Andras Kovács and Eszter Andor, 103-123. Budapest 2002.

Keil, Martha. “Public Roles of Jewish Women in Fourteenth and Fifteenth- Centuries Ashkenaz: Business, Community, and Ritual.” In The Jews of Europe in the Middle Ages (Tenth to Fifteenth Centuries), edited by Christoph Cluse, 317-330. Turnhout: Brepols, 2004.

Kraemer, Ross S. Her Share of the Blessings: Women’s Religions Among Pagans, Jews and Christians in the Greco-Roman World. New York and Oxford: 1992.

Lamdan, Ruth. A Separate People: Jewish Women in Palestine, Syria and Egypt in the Sixteenth Century. Leiden and Boston: 2000.

Lew, Myer S. The Jews of Poland: Their Political, Economic, Social and Communal Life in the Works of Rabbi Moses Isserles. London: 1944.

Luria, Shlomo. Responsa of the Maharshal (Hebrew). Lemberg: 1859. Marcus, Ivan G. “Mothers, Martyrs, and Moneymakers: Some Jewish Women in Medieval Europe.” Conservative Judaism 38 (1986): 40–77.

Marcus, Jacob R. The Jew in the Medieval World: A Sourcebook: 315–1791. 1938. Reprint, New York: Atheneum, 1974.

Meir ben Barukh. The Responsa of the Maharam, Prague Edition (Hebrew). 1893. Reprint, Tel Aviv: 1969–1970; Porten, Bezalel. The Elephantine Papyri: Three Millennia of Cross-Cultural Continuity and Change. Leiden: 1996.

Shmuelovitz, Aryeh. The Jews of the Ottoman Empire in the Late Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. Leiden: 1984.

Stern, Selma. The Court Jew: A Contribution to the History of the Period of Absolutism in Central Europe. Rpt. New Brunswick, NJ: 1985. 47–50.

Stow, Kenneth, and Sandra Debenedetti Stow. “Donne ebree a Roma nell’eta del ghetto: affeto, dipendenza, autonomia.” Rassegna Mensile di Israel 52 (1986): 63–116.

Taitz, Emily, Sondra Henry, Cheryl Tallan. The JPS Guide to Jewish Women, 600 B.C.E —1900 C.E. Philadelphia: 2003.

Tcherikover, Victor and Alexander Fuks, eds. Corpus Papyrorum Judaicarum. Vol. 1. Cambridge, Mass.: 1957.

Toch, Michael. “Selbstdarstellung von mittelalterlichen Juden.” Bild und Abbild vom Menschen im Mittelalter Akten der Akademie Friesach. “Stadt und Kultur im Mittelalter,” Friesach (Kärnten), September 9–13, 1998, Klangenfurt: 1999, 173–192.

Weinryb, Bernard D. The Jews of Poland: A Social and Economic History of the Jewish Community in Poland from 1100–1800. Philadelphia: 1982.

Winer, Rebecca. Women, Wealth, and Community in Perpignan c. 1250–1300: Christians, Jews, and Enslaved Muslims in a Medieval Mediterranean Town. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005.

Yadin, Yigael. “Expedition D: The Cave of Letters.” Israel Expedition Journal 12 (1962): 235–238.

Zives, Franz. “Reynette—eine jüdische Geldhändlerin in spätmittelalterlichen Koblenz.” Koblenzer Beiträge zur Geschichte und Kultur 4 (1994): 25–40.