Dulcea of Worms

Dulcea of Worms was the wife of Rabbi Eleazar ben Judah of Worms, a major rabbinic figure. They were part of the elite leadership class of medieval Germany Jewry. In November 1196, Dulcea and her two daughters were murdered. Eleazar’s moving poetic and prose accounts of the incident are an important source for the activities of medieval Jewish women. Dulcea was a capable businesswoman and a moneylender who supported her household financially. She also managed this extensive household and was renowned for her needlework. Dulcea had a more extensive Jewish education than most women of her time and is among several medieval Jewish women who are described as leading prayers for other women. She also took on communal responsibilities relating to women, arranging matches and adorning brides.

Dulcea of Worms (sometimes transliterated as Dolce) came from the elite leadership class of medieval German Jewry. She was the daughter of a cantor and the wife of a major rabbinic figure, Rabbi Eleazar ben Judah of Worms (1165–1230), also known as the Roke’ah (the Perfumer), after the title of one of his most famous works (Sefer ha-Roke’ah). Dulcea and her husband were members of a small pietistic circle of Jews, the Hasidei Ashkenaz, that developed following the devastations of the First Crusade of 1096. The documents of this movement include many mystical works, as well as a volume reflecting their ethical concerns, Sefer Hasidim (The Book of the Pious), an important historical source for everyday Jewish life in medieval Ashkenaz. R. Eleazar ben Judah may have written some of the passages in Sefer Hasidim, and could have been its editor.

Accounts of the Attack

Among R. Eleazar ben Judah’s surviving writings are two accounts, one in prose and one in poetry, that describe the lives and the deaths of his wife Dulcea , and their daughters, Bellette and Hannah, who were murdered in November, 1196. According to these texts, two armed men, who had apparently gained entry to the family dwelling, set upon those present, including R. Eleazar, his wife, two daughters, at least one son, a number of students, and a junior teacher. Many scholars have assumed the attackers were Crusaders. There were, however, no massed Crusader forces in Germany at this time. While the two miscreants may have worn Crusader markings, they appear to have attacked the family out of criminal motives. Dulcea was a moneylender who supported her household financially and she was probably known to have valuable objects in her home. These assaults did not go unpunished. The local authorities, in accordance with the German Emperor’s mandate of protecting the Jews of his realm, quickly captured and executed at least one of the men.

The prose narrative describes the attack and its aftermath while the poetic elegy recounts the range of endeavors of “the saintly Mistress Dulcea” and her daughters. Based in part on Proverbs 31, the biblical acrostic describing the “woman of valor,” this poem, in the form of an expanded alphabetic acrostic, records numerous poignant details of its subjects’ daily lives. Together these documents constitute an important source for the activities of medieval Jewish women in general, as well as a moving tribute to Dulcea and her daughters. Three times in the prose account and again at the very outset of the poem, Eleazar describes his wife as “pious” or “saintly” (hasidah). He also uses the Hebrew ne’imah, “pleasant,” three times in the elegy, a play on the meaning of Dulcea’s name, which is derived from the Latin adjective dulcis, “agreeable, pleasant, kind.” Medieval Jewish women often had vernacular rather than, or in addition to, Hebrew names. Of Dulcea’s two daughters, one was known by a vernacular name, Bellette, while the other was referred to by a Hebrew name, Hannah.

Dulcea's Economic & Communal Activities

In both his prose and poetic laments, Eleazar describes Dulcea’s economic activities. A capable businesswoman, she was apparently entrusted with the funds of neighbors which she pooled in order to lend at profitable rates of interest on which she received commissions. She also managed an extensive household including her husband’s students and at least one teacher. In addition, she was renowned for her needlework. Dulcea is credited with preparing gut thread and sewing together books and forty Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah scrolls and is said to have spun thread for other religious objects. She is also said to have prepared candles for synagogue use.

Dulcea had a more extensive Jewish education than most women of her milieu. She is among several medieval Jewish women who are described as leading prayers for other women. Her husband wrote, “In all the cities she taught women, enabling their ‘pleasant’ intoning of songs.” In her prominent role as rabbi’s wife, Dulcea took on other communal responsibilities relating to women. She is described as adorning brides and bringing them to the wedding canopy in honor. As a respected investment broker, Dulcea may have been involved in arranging matches and negotiating the financial arrangements which accompanied them. She is also said to have bathed the dead and to have sewn their shrouds, acts considered particularly meritorious in Jewish tradition.

Dulcea's Piety & Legacy

R. Eleazar stresses Dulcea’s piety in both the prose and poetic texts, stating that all of her actions were inspired by a desire to obey God, the pietist’s highest goal. She is described as knowing what was permitted and what was forbidden according to The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhah and as always eager to learn from her husband’s words. Dulcea was teaching her daughters to follow in her footsteps; their father mentions not only their needlework skills, but also their knowledge of Hebrew prayers and melodies. In everything, as the Roke’ah puts it in the poetic lament, Dulcea was concerned to “fulfil her Creator’s commandments.”

R. Eleazar’s final words of praise for Dulcea are that she rejoiced to perform her husband’s will and never angered him, an expression of his fundamental agreement with the rabbinic view that a woman earns merit by enabling her male relatives to study and pray. Dulcea is revered above all else for facilitating the spiritual activities of the men of her household. In the final phrase of the poetic lament, R. Eleazar envisions his beloved wife wrapped in the eternal life of Paradise, a worthy reward for the deeds upon which so many were dependent. While this idealized portrait certainly contains formulaic elements, there can be no doubt of its author’s deep grief at the loss of his wife and daughters. Although the Roke’ah’s memorializations of Dulcea, Bellette, and Hannah are framed by male assumptions about what constitutes admirable female behavior, they nonetheless provide important insights into Jewish women’s lives in an era from which independent female voices do not survive.

Baskin, Judith R. “Dolce of Worms: The Lives and Deaths of an Exemplary Medieval Jewish Woman and her Daughters.” In Judaism in Practice: From the Middle Ages through the Early Modern Period, edited by Lawrence Fine, 429–437. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001.

Includes English translations of all of the documents related to Dulcea and a discussion of Dulcea’s activities.

Baskin, Judith R. “Women Saints in Judaism: Dolce of Worms.” In Women Saints in World Religions, edited by Arvind Sharma, 39-70. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2000.

This article delineates all the documents (both contemporary and later) connected with the attack on the Roke’ah and his family and its ramifications, and illuminates the historical context in which these events took place.

Haberman, Abraham M., ed. Sefer Gezeirot Ashkenaz ve-Zarfat. Jerusalem: N.p., 1945.

Hebrew versions of the documents concerning Dulcea appear pp.164–167.

Kamelhar, Israel. Rabbenu Eleazar mi-Germaiza, ha-Roqeah. Rzeazow: N.p., 1930.

Hebrew versions of the documents concerning Dulcea appear pp. 17–19.

Marcus, Ivan G. “Mothers, Martyrs, and Moneymakers: Some Jewish Women in Medieval Europe.” Conservative Judaism 38, no. 3 (Spring 1986): 34–45.

Includes an English translation of R. Eleazar ben Judah’s poetic elegy for Dulcea.

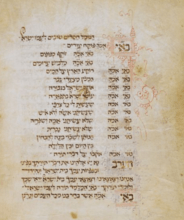

Neubauer, Adolf, ed. Catalogue of the Hebrew Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library and in the College Libraries of Oxford (Oxford, 1886–1906), 762, 798.

The relevant manuscripts in the Bodleian Library are Hebrew MS Michael 448, folio 30, and Hebrew MS Oppenheim 757, folios 25–27.

Taitz, Emily. “Kol Ishah—The Voice of Woman: Where was it Heard in Medieval Europe?” Conservative Judaism 38, no. 3 (Spring 1986):46–61.

Taitz, Emily. “Women’s Voices, Women’s Prayers: Women in the European Synagogues of the Middle Ages.” In Daughters of the King: Women and the Synagogue, edited by Susan Grossman and Rivka Haut, 59–71. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1992.