Babatha

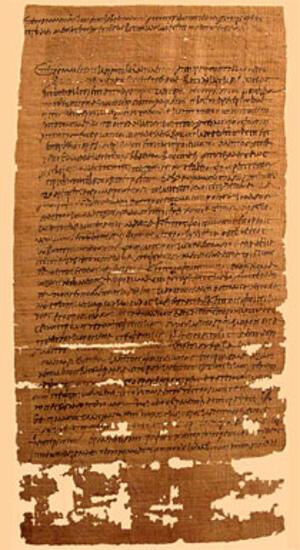

Registration document for four date orchards owned by Babatha, a second century Jewish woman. One of the 35 separate papyrus scrolls belonging to her that were found in the Cave of Letters.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The story of Babatha’s life demonstrates the differences between the ideal world of the Mishnah and the real lives of second-century Jews, especially women, in Greco-Roman Palestine. Widowed several times during her life, Babatha repeatedly fought for her rights to property and repayment in court; her numerous legal battles, as well as information about women’s other activities at the time, are recorded in the contracts, deed,s and other documents found in Babatha’s archive.

Babatha daughter of Shim’on, a Jewish landowner who lived in Roman Arabia, owned a document archive found in a cave in the Judaean desert. The following biographical information derives from the documents found in this archive.

Early Life and First Marriage

Babatha was born around the turn of the second century C.E., probably in the large village of Mahoza, south of the Dead Sea. The village was predominantly Nabatean in population makeup, but a sizeable Jewish community was formed there between the two revolts against Rome (73–132 C.E.). Babatha’s father Shim’on came from En-Gedi to Mahoza together with other Jews around the time of her birth and bought property in the village. Babatha seems to have been his only child. Although nothing is stated specifically in the deed of gift he left to his wife (Miryam daughter of Menahem), where Babatha is first mentioned in 120 C.E., when he died his daughter apparently inherited his property in Mahoza, which consisted of several date orchards. In 124 C.E., the date of the first document belonging to Babatha in the archive, she is already a mother and a widow. Her first husband, Jesus (Yeshua) left her a son by the same name and Babatha’s first legal battle was fought against the guardians nominated for him by a Roman court of law in Petra. Babatha thought the guardians had not invested his estate properly and it was thus not producing for him the sort of income he deserved and could expect.

Second Marriage and Legal Battles

By 127 C.E. Babatha was married for a second time to a Jew from En-Gedi by the name of Judah son of Eleazar Ketushyon. The man must have been much older than Babatha for at the time of his second marriage he had in En-Gedi another living wife, Miryam daughter of Beianus, and a daughter of marriageable age, Shelamziyyon. The relations between Babatha and her second husband were economic as well as marital. He accompanied her to Rabbath Moab in 127 to declare her property in Mahoza to the Roman governor of Arabia during a Roman census, and also served as her legal guardian in the process. She lent him money in February 128, apparently to cover the gift he gave his daughter on the occasion of her wedding in April of that same year.

By June 130 C.E. Babatha was widowed again. Her legal battles, however, were just beginning. In September of the same year we find her appropriating her late husband’s date crop in lieu of her marriage settlement, which had apparently not been paid by his family. In July 131 we find her embroiled in a legal battle with her co-wife over the possessions of their dead husband.

Preserving the Documents

The last of Babatha’s documents dates from August 132 in Mahoza. We can only guess what happened to her between this date and the end of the Bar Kokhba revolt against Rome in 135, when her documents were carefully deposited in a cave inhabited by rebel refugees, who fled En-Gedi when the Roman forces occupied it. Babatha, together with other Jewish inhabitants of Mahoza, fled the village either because they felt threatened by the local population, or because the Jewish rebellion had impinged on the neighboring Roman province of Arabia. She found refuge in a cave in Nahal Hever, together with the family of Jonathan son of Beianus, Bar Kokhba’s general in En-Gedi, who was apparently her co-wife’s brother. The fate of the refugees in the cave is not known, but we can assume that they died in the desert.

Babatha’s archive is an extremely important resource for many issues, especially on the question of Jewish women’s legal position in Greco-Roman Palestine. It demonstrates the extent to which Jews reverted to a Jewish code of personal law and the extent to which they relied on the Greco-Roman legal system and the law courts it provided to enforce this system. It serves as a corrective to the impression that one may derive from rabbinic literature that the Codification of basic Jewish Oral Law; edited and arranged by R. Judah ha-Nasi c. 200 C.E.Mishnah and its commentaries (the Jerusalem and Babylonian Talmuds) dictated Jewish women’s position. It allows us a glimpse into specifically feminine documents used by Jewish women, such as marriage contracts and deeds of gift, revealing what they looked like and how they compare with the literary documents described in rabbinic sources. But it also shows us less specifically feminine activities in which women were involved—ownership of agricultural property and its management, guardianship of orphans and a mother’s outsider position vis-à-vis her son, women as money lenders and even women’s (il)literacy.

Cotton, Hannah M. “The Guardianship of Jesus son of Babatha: Roman and Local

Law in the Province of Arabia.” Journal

of Roman Studies 83 (1993): 393–420.

Hannah Cotton is the foremost scholar on Babatha. She has written numerous

articles on various aspects of the documents in her archive. This one discusses

Babatha’s legal battles over her son’s guardianship and what she may have

hoped to achieve in a Roman court of law.

——. “Subscriptions and Signatures in the Papyri from the Judaean Desert: The

Χειροχήστης,”

Journal

of Juristic Papyrology 25 (1995): 29–40.

This article discusses Babatha’s declared illiteracy in the wider context

of illiterate persons seeking court assistance in the Roman period.

——. “The Guardian (epitropos) of a Woman in the Documents from the Judaean

Desert,” Zeitschrift

für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 118 (1996): 267–73.

In all Babatha’s documents executed for a Roman court of law a male guardian

accompanies her. Cotton discusses this institution in its historical and legal

setting.

—— with J.C. Greenfield, “Babatha’s Property and the Law of Succession in

the Babatha Archive,” Zeitschrift

für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 104 (1994): 211–24.

In this article Cotton conflates the geographical data from Babatha’s and

other women’s legal document to suggest an interesting law of succession practiced

in the Judaean Desert which discriminated against daughters even over and

against their uncles.

Ilan, Tal. “Women’s Archives in the Judaean Desert.” In The

Dead Sea Scrolls: Fifty Years after their Discovery 1947–1997, eds.

L. Schiffman, E. Tov and J. VanderKam, 755–60. Jerusalem: 2000.

This article discusses the contents of women’s archive in antiquity in light

of the Babatha archive and two other archives of women from the Judaean Desert.

Katzoff, Ranon. “Polygamy in Papyrus Yadin” Zeitschrift

für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 109 (1995): 128–32.

In this article Katzoff suggests a different reading of some of the Babatha

documents, suggesting that her second husband was not married to both his

wives simultaneously.

Lewis, Naphtali. The

Documents from the Bar-Kokhba Period in the Cave of Letters: Greek Papyri.

Jerusalem: 1989.

This is the publication of all Babatha’s Greek documents.

Peters, Sigrid. “Caves, Documents, Women: Archives and Archivists.” The

Dead Sea Scrolls: Fifty Years after their Discovery 1947–1997, eds.

L. Schiffman, E. Tov and J. VanderKam, 761–72. Jerusalem: 2000.

This article examines the archeological context in which Babatha’s archive

was discovered and suggests that women in general may have served as archivists

for documents at the time.

Yadin, Yigael, J.C. Greenfield, A. Yardeni. “Babatha’s Ketubba,”

Israel

Exploration Journal 44 (1994): 75–101.

This is the publication of Babatha’s second (Aramaic) marriage contract.

——. “A Deed of Gift in Aramaic found in Nahal

Hever:

Papyrus

Yadin 7,” (Hebrew). Eretz

Israel 25 (1996): 383–403.

This is the publication of the Aramaic deed of gift Babatha’s father wrote

for her mother.