Hasidic Hebrew Fiction: Portrayal of Women

Hundreds of compilations of Hasidic literature were published in Eastern Europe between the start of the nineteenth century and the outbreak of World War II. Derived from oral traditions that were passed down among the Hasidim from the movement’s beginnings, this genre of literature included women to a much greater degree than most types of traditional Hebrew literature, allowing us to peek into their world via stories that, in passing, describe their characters and lives. Yet despite the large number of women characters in Hasidic literature, it is impossible to relate a singular image of “woman” in Hasidism or even in Hasidic literature; we can only refer to individual women.

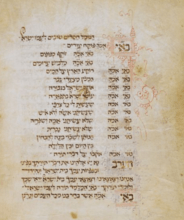

Hundreds of compilations of Hasidic literature were published in Eastern Europe from the start of the nineteenth century until the outbreak of World War II. This literature derived from oral traditions that were passed down among the Hasidim from the movement’s beginnings. Many stories were printed without processing or calculated editing in an attempt to preserve the tradition as intact as possible.

The relatively large amount of attention paid to women in Hasidic literature is not the result of any specific thought or belief but rather due to the fact that this literature is, as Martin Buber put it, a “life category” (Buber, Be-Pardess ha-Hasidut). Consequently, the frequent presence of women in everyday life dictates that here, too, they are found to a much greater degree than in most types of traditional Hebrew literature. Thus we are enabled to peek into the world of these women via stories that, in passing, describe their characters and lives. It is possible that many things written about women in the Hasidic world are no different from those written about their counterparts in the non-Hasidic world. Yet only in Hasidic literature, amid the many and varied compilations of Hasidic stories, do we find traces of many women.

Despite the large number of women characters in Hasidic literature, it is impossible to relate to the image of “woman” in Hasidism or even in Hasidic literature, since this would be to assume a priori that Hasidism , or Hasidic literature, espoused a specific position on the subject. In fact, no such position existed, and the attitudes varied according to the character in the story, its narrator and its setting in time and place. Therefore we can only refer to individual women, each on her own, and not to woman in general or women as a gender.

Women in Shivhei Ha-Besht

Shivhei ha-Besht (1815), the first published work of Hasidic literature, reflects the Hasidic experience of the eighteenth century. It contains many prominent women characters, starting with the women surrounding the Besht (Israel ben Eliezer Ba’al Shem Tov, c. 1700–1760) during his lifetime—his mother, wife and daughter—and ending with women who were possessed by a dibbuk or non-Jewish women who practiced sorcery. Also conspicuous is the proportion of women among those who came to the Besht for help and advice. In his essay “Women in Shivhei ha-Besht” (Molad 6, 1974), Gedalyah Nigal writes that about one-sixth of the stories in the book mention women. Yet this statistic applies only to Shivhei ha-Besht. In later Hasidic literature, printed from 1864 on, the appearance of women is extremely rare. The most prominent female character, on her own merit and not merely because she was the wife, mother or daughter of an important person, is a woman known as “di frume Riveleh” (Riveleh the pious). Riveleh is presented as an assertive woman who clings to her performance of A biblical or rabbinic commandment; also, a good deed.mitzvot. She haggles with the Besht several times about the amount of the donation he must give her “for the city’s poor and ill” and about her request that he pray for the recovery of a sick physician. The Besht tries to avoid granting her request on the grounds that the physician is an adulterer. While Riveleh does not deny this, still she tries to speak in his favor. The negotiations between herself and the Besht are noted at length, with the woman depicted as the stronger party, with right on her side. No other confrontation of this sort between a great Jewish scholar and a woman is to be found in any other kind of Orthodox Jewish literature of this period.

Shivhei ha-Besht depicts the Besht’s loving, appreciative treatment of his wife and daughter. The relationship between the Besht and his wife (his second; his first wife, who died young, has no independent existence in the book) is outstanding in its mutual esteem and the feeling of partnership between them. Even at the beginning of their life together, the Besht’s wife Hannah (whose name is mentioned only once) is shown as the person closest to him and his confidante. She is the only person to whom, prior to their marriage, he revealed his true inner nature, and she also covers for him and helps him to conceal his secret from the eyes of others. The closeness between the Besht and his wife is also noted in later Hasidic sources. For example, in Hitgalut ha-Zaddikim (Shlomo Gabriel Rosenthal, Warsaw: 1901) she is termed “his pure partner, the lady Hannah,” and the book also shows that the Besht included his wife in his spiritual world. As for his son and daughter, it is evident that his relationship was especially affectionate towards the latter, Adel, who later became the mother and grandmother of prominent Hasidic zaddikim: Rabbi Baruch of Medzibezh (1757–1810), Rabbi Moses Hayyim Ephraim of Sudylkow (c. 1740–1800?) and Rabbi Nahman of Bratslav (1772–1811).

The frequent presence of women in Shivhei ha-Besht may be due to the Besht’s own sympathetic and appreciative attitude toward the women around him and toward women in general.

Women in Later Hasidic Literature

More than fifty years separate the publication of Shivhei ha-Besht from that of hundreds of later collections of stories. These thus constitute a completely separate literary entity, one of the differences between the compilations and Shivhei ha-Besht being the frequency with which women are mentioned. Though they appear far less frequently in the later works, nevertheless one can find quite a few female characters, who fall into two main categories: women who themselves or with the aid of relatives seek the blessing or advice of the zaddikim, and women who are related to the zaddikim: mothers, wives, daughters and, on occasion, sisters.

An exception is to be found in Imrei Zaddikim, a collection of Hasidic short essays and stories compiled by Rabbi Abraham Ittinga and printed in Lvov in the 1930s. One chapter of the book, entitled “The Wisdom of Women,” contains short stories and proverbs of women, all of them from the families of zaddikim.

Women Helped by the Zaddik

Women who ask for the help of a zaddik are usually childless, have difficulty giving birth, seek salvation from the zaddik through their husbands, or are agunot. The agunot seem to constitute the largest group of women who themselves come to the zaddik to ask for help. There are stories of many zaddikim who helped agunot, most prominent among them being the Maggid of Koznitz (Israel ben Shabbetai Hapstein of Kozienice, 1733–1814). The large number of stories about his aid to agunot may be the result of the considerable extent to which he dealt with this topic, which is also the subject of Agunot Yisrael, his book on the laws permitting agunot to remarry. Even non-Jewish women who came to seek his blessing and healing appear in the stories.

Agunot turned to him and to other zaddikim for help primarily because of their supernatural powers and ability to work miracles. The women hoped that through the zaddik they would receive the divorce they desired, confirm the absent husband’s death or, in rare cases, succeed in bringing about his return.

Although agunot, childless women and women who had difficult births contacted many of the zaddikim, according to the stories, the women are not depicted as possessing any unique characteristics. They are not referred to by name or by any identifying detail, but exist solely in order to convey the power and greatness of the zaddik.

Women of the Zaddik’s Family

We can find more specific characterizations and a certain amount of penetration into women’s lives and their world in a number of stories about women members of a zaddik’s family. Occasionally the description of the goings-on in the zaddik's household enables us to learn about certain customs regarding women, which varied from place to place. Rabbi Jacob Isaac, the Seer of Lublin (1745–1815), was amazed to find on a visit to Rabbi Baruch of Medzibezh, the Ba’al Shem Tov’s grandson, that the women of the family sat at the table together with the men. This shows us that the practice did not exist among the Hasidim of Poland.

Sometimes the women of the family are mentioned by name, but even then they are not distinguished from each other by their character or through events in their lives. Although Miriam, the sister of Rabbi Samuel Shmelke of Nikolsburg (1726–1778), is mentioned by name and called “the zaddeket,” all anyone wanted of her was that she tell stories about her brother the zaddik.

Perl, daughter of Rabbi Israel, the Maggid of Kozienice (1736–1814), is mentioned in several stories, but always in connection with her father or her son, Rabbi Hayyim Jehiel, the Seraph of Mogielnica (1789–1849).

The mother of Rabbi Uri of Strelisk (d. 1826) is said to have been an orphan of whom people spoke ill. Rabbi Levi Isaac of Berdichev (c. 1740–1810) assured a poor young man that the rumors were false and that once they married, they would have a son like himself. Here, too, the woman has no status of her own but exists between the blessing and prophecy of one zaddik and the birth of another.

The wife of Rabbi Jacob Isaac, the Seer of Lublin, is mentioned mostly for her complaints about her childlessness and her part in the conflict between her husband and Jacob Isaac of Przysucha (Pshiskhah), the “Holy Jew” (1766–1814). The Hasidic story attributes much of the mutual tale-telling and fanning of the conflict to the wives of both zaddikim.

Even women in this group of female family members of zaddikim are not depicted as individuals. They are simply part of the “human scenery” surrounding the zaddikim, the protagonists of the Hasidic tale.

The Zaddik and His Wife

Only in the rarest instances can we learn about the relationship between zaddikim and their wives. Usually, the Hasidic story does not mention the subject at all. As mentioned above with reference to Shivhei ha-Besht and other sources, the Besht and his wife enjoyed an exceptionally good relationship. Among the zaddikim mentioned in later works, the relationship between Rabbi Simhah Bunem of Przysucha (Pshiskhah, 1765–1827) and his wife Rivkeleh is especially remarkable. Like the accounts of the Besht and his wife, and perhaps even more so, the stories indicate that Rabbi Simhah Bunem included his wife in both his spiritual world and his work in his pharmacy. The connection between the couple is especially noteworthy in view of the complete lack of mention of the wives of other zaddikim. Indeed, the stories note their good relationship and mutual trust briefly and with few words, as is typical for the genre.

Of the wife of Rabbi Shalom Rokeah of Belz (1779–1855) it is said that she was renowned for her high spiritual attainment and that her husband would do nothing without her. It is also said of her that she would often accompany her husband, even when they were among rabbis, and “remained awake with her husband for a thousand nights,” helping him in his spiritual work. The partnership and mutual support between the two led to their being seen “like Adam and Eve before the Fall,” and the room where they dwelt as the Garden of Eden.

In recent times, a story which in the version by Shmuel Yosef Agnon (1888–1970) is called “The Zaddik’s Etrog,” deals with Rabbi Jehiel Michael (“Michel”) of Zloczow (c. 1731–1786) and his wife. In this version of the story, the relationship between the zaddik and his wife is filled with tension and bitterness on the wife’s part because her husband sold his valuable Phylacteriestefillin for an etrog. An earlier Hasidic tale (Sippurei Zaddikim he-Hadash, edited by Abraham Isaac Soibelman, Piotrkow 1909–1910) has a completely different version of the relationship between Rabbi Jehiel Michael of Zloczow and his wife, told in the name of their son, Rabbi Joseph of Yampol (d. 1812). Here, the wife of her own free will gives her last valuable possession to her husband so he can purchase an etrog, and the relationship between the two is exceptionally harmonious. The husband and son even mention her as having merited a revelation of Elijah the Prophet.

In another instance, the story reveals two completely different relationships that the zaddik has with his two wives. While Rabbi Jacob Isaac of Przysucha, the “Holy Jew,” enjoyed a relationship of trust with his first wife, his relationship with his wife’s sister, whom he married after his wife’s death, was so unpleasant that, as the story recounts, the “Holy Jew” hinted at her in his story about the angel whose punishment was to be sent to live on earth with a bad wife.

We know very little about the relationships of the majority of zaddikim with their wives or other female family members. In most cases, these relationships were apparently not considered sufficiently important to deserve the attention either of the zaddik’s close associates or the storytellers.

Women as Unique Personalities

In the most unusual instances, stories do delve more deeply into the lives of individual women such as the Lady Baila, mother of Naphtali Zevi of Ropshits (1760–1827), who was known for her wisdom and sharp wit. The clever wordplays attributed to her would have made any Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmud student or zaddik proud. Yet we hear very little about her life aside from these few witty comments.

A lesser-known figure, who is the major protagonist in one story and whose wisdom and strong personality triumph over her father and husband, is Raizeleh, the daughter of Rabbi Joshua Asher of Presov (1804–1862), the son of the Holy Jew of Przysucha (Pshiskhah), and the wife of Rabbi Moses of Zelechow. When her husband complained to her father that she gave more money to charity than he could afford, she justified herself by sophisticated The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhic arguments, so that her father had to admit that “there was justice in her words, and he praised her statements every time.”

Yet even about (Yiddish) Rabbi's wife; title for a learned or respected woman.Rebbetzin Zizia Hannah, daughter of Rabbi Ze’ev Wolf, a woman described as a zaddeket whom, according to the stories, “Hasidim and even zaddikim would visit,” nothing is related that could enlighten the reader about her life or personality. “She functioned as a rebbe after the death of her saintly husband, Rabbi Israel Abraham of Chernyostrov (1772–1814), son of Rabbi Zusya of Hanipoli (d. 1800). Hasidim streamed to her as they did when her husband, the holy rabbi and zaddik, was alive. Once Rabbi Mordechai of Chernobyl (1770–1837) stayed in Chernyostrov for the Sabbath and went to the rebbetzin for the third meal.” While this little story expresses great admiration and respect for the rebbetzin, it contains not the slightest bit of information about her characteristics, personality, actions or life.

There is a certain difference in Habad Hasidism, perhaps because of the special relationship between Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Lyady (1745–1813), founder of the Habad movement, and his daughters. But the literature of this particular branch of Hasidism, like that of Bratslav, constitutes a completely separate section of Hasidic literature.

Even if the incidents described in the stories are historically questionable, they still give the reader a general picture of a specific character or relationship. This is true of characters in Hasidic stories in general and also of women characters. Thus, while it may be unclear whether the quotations attributed to Rabbi Naftali’s mother are accurate, what other statements she made and what she did, it is nevertheless clear that she was regarded as wise and assertive. Similarly, we cannot be certain whether the stories describing the relationship between the Besht and his wife or Rabbi Simhah Bunem with his wife really occurred. Yet the consistency of the stories that describe the good relationship between these figures leads us to conclude that in these instances each couple enjoyed an especially good relationship. On the other hand, it seems that even if the stories exaggerate and distort, we can see that the Seer of Lublin’s third wife and the Holy Jew of Przysucha’s second wife were prone to slander and provoking quarrels.

As a rule, we can say that women’s place in the Hasidic story is not more marginal than that of others in the community who were not themselves zaddikim. The advantage of Hasidic literature is that it describes the way of life and the daily lives of those it depicts, even as incidental characters. As such, it depicts a relatively large number of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century women characters, who appeared only rarely in other literary genres.

Biale, David. “A Feminist Reading of Hasidic Texts.” In Lift Up Your Voice, edited by Renée Levine Melammed, 125–144 (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: 2001.

Dvir-Goldberg, Rivka. “The Voice of an Underground Spring: Images of Women in Hasidic Literature” (Hebrew). Jerusalem Research on Jewish Folklore 21 (2001): 27–44.

Idem. “Views of Women in Hasidic Tales: Israel Ba’al Shem Tov and His Wife” (Hebrew). Massekhet 3 (2005): 45–63.

Leventhal, Naftali. “Women in Hasidism.” Dimuy 21 (summer 2002): 27–31.

Nigal, Gedalyah. “Women in Shivhei ha-Besht” (Hebrew). Molad 6 (1974): 138–145.

Idem. Women in Hasidic Literature (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 2005.

Oron, Michal. “The Woman as the Narrator in the Hasidic Story. A Literary Strategem or Preservation of Tradition? A Study of S.Y. Agnon’s ‘The Etrog (Citron) of That Zaddik.’” In Studies in East European Jewish History and Culture in Honor of Professor Shmuel Werses, edited by David Assaf, Israel Bartal, Shmuel Feiner, Yehuda Friedlander, Avner Holtzman and Chava Turniansky, 513–529 (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 2002.

For further reading on attempts to find women’s place in Hasidic literature, see: Horodezky, Samuel Abba. “Jewish Women in Hasidism.” In Hasidism and Hasidim. Tel Aviv: 1943, 67–41, and Ada Rapoport’s response to Horodezky: Rapoport-Albert, Ada. “On Women in Hasidism: S. A. Horodezky and the Maid of Ludomir Tradition.” In Jewish History: Essays in Honor of Chimen Abramsky. London: 1988, 495–525.