Infertile Wife in Rabbinic Judaism

The prooftext of Genesis 35:11 only legally obligates men to procreate. The rabbis view procreation as the masculine expression of potency – different than the feminine role of giving birth to the fruit of the male seed. They were also concerned about the possibility of female attempts at reproductive independence. Tosefta Yevamot 8:6 states that a man must divorce his wife is they are childless after ten years of normal marital relations. In contrast, rabbinic aggadic writings do not view the obligation to reproduce as paramount in the case of a childless but otherwise happy couple. Regardless, Genesis acknowledges the suffering and shame of a barren wife. And yet the initial infertility of the matriarchs reinforces the efficacy of prayer by demonstrating that the individual matriarchs’ suffering and supplications are what provoked a divine response.

Male Obligation to Procreate

Rabbinic Judaism constructed differing legal, religious, and social roles for men and women that were intended to foster women’s reproductive functions and nurturing qualities, even as it placed them under the control of a dominant husband. While childlessness was perceived as a grave misfortune for both men and women, a male’s failure to generate offspring violated a legal obligation, since men alone were obligated to have children. The prooftext frequently cited for this unilateral ruling was Genesis 35:11, where Jacob is commanded in the second person masculine singular to “Be fertile and increase.” According to BT Pesahim 113b, the childless man is reckoned as if menuddeh, “cut off” from all communion with God, like one who has deliberately disregarded divine commands. BT Nedarim 64b, among other texts, accounts him as already dead, together with the pauper, the leper, and the blind. BT Sanhedrin 36b ordains that the childless scholar may not sit on the Sanhedrin. The primary The Day of Atonement, which falls on the 10th day of the Hebrew month of Tishrei and is devoted to prayer and fasting.halakhic statement on procreation is found in The Day of Atonement, which falls on the 10th day of the Hebrew month of Tishrei and is devoted to prayer and fasting.Mishnah

Yevamot 6:6 and is further elaborated in BT Yevamot 65b–66a. According to Mishnah Yevamot 6:6:

No man may abstain from keeping the law “Be fertile and increase” (Gen. 1:28), unless he already has children: according to the School of Shammai, two sons; according to the School of Hillel, a son and a daughter, for it is written, “Male and female He created them” (Gen. 5:2). If he married a woman and lived with her ten years and she bore no child, it is not permitted him to abstain [from fulfilling this legal obligation]. If he divorced her she may be married to another and the second husband may live with her for ten years. If she had a miscarriage the space [of ten years] is measured from the time of the miscarriage. The duty to be fruitful and multiply falls on the man but not on the woman. R. Johanan b. Baroka [dissents from this view and] says: Of them both it is written, “God blessed them and God said to them, Be fertile and increase” (Gen. 1:28).

In the talmudic discussion of the final segment of this Mishnah in BT Yevamot 65b–66a, a majority of rabbis affirm that the obligation to procreate is limited to men. A significant minority of sages, however, express uneasiness with exempting women from the responsibility to fulfill the commandment. Some were uncomfortable with the modification of the plural imperative verbs of the biblical text “Be fertile and increase” (Genesis 1:28) to masculine singular forms. Moreover, to eliminate women from the directive also undermined the actions of such biblical women as Lot’s daughters (Genesis 19:31–36), and Tamar (Genesis 38), who took their obligation to procreate seriously enough to flout social custom, or even Rachel, whose poignant cry, “Give me children, or I shall die” (Genesis 30:1), became a standard rabbinic prooftext for obligatory male propagation.

Passive Reproductive Role of Women

Arguments tendered in BT Yevamot 65b–66a in support of the Mishnah’s ruling maintain that the biblical ordinance had to be modified from a plural to a singular form because “It is the nature of a man to master but it is not the nature of a woman to master.” For the rabbis, procreation is a masculine expression of potency quite different from the feminine role of bearing and giving birth to the fruit of male seed. In BT Berakhot 51b, the Palestinian sage Ulla explained his refusal to allow Yalta, a prominent Jewish woman in the Babylonian community, to participate in sharing the cup of benediction that concludes the recitation of grace after a meal on the grounds that the blessing did not apply to her because of her passive role in reproduction. His statement, attributed to R. Johanan, that “the fruit of a woman’s body is blessed only from the fruit of a man’s body,” is another way of indicating that woman’s role in the procreation process is secondary.

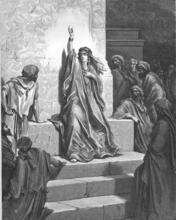

BT Yevamot 65b–66a also suggests that obligating women to procreate when they are incapable of doing so on their own would teach them to scorn the law in general. Another explanation invokes the necessity of male control over female sexuality to prevent promiscuity and uncertain lineages of offspring, while a third opinion suggests that this limitation promotes peace. Indeed, preventing disruptions was a primary goal of the rabbis’ social agenda. Concern about possible female attempts at reproductive independence, even for worthy purposes, is apparent in the discussion of a segment of Hannah’s prayer (1 Samuel 1:11) in BT Berakhot 31a–b. According to Numbers 5:28 the wife falsely accused of adultery will be cleared and will subsequently conceive: “And if the woman has not defiled herself and is pure, she shall be unharmed and able to retain seed.” Commenting on a portion of Hannah’s supplication, “If you will look” (I Samuel 1:11), R. Eleazar interpreted Hannah’s motivation as follows:

Hannah said before the Holy One, blessed be He: Sovereign of the Universe, if You will look [upon my affliction], it is well, and if You will not look, I will go and shut myself up with another man in the knowledge of my husband Elkanah, and as I shall have been alone [with this other man in compromising circumstances] they will make me drink the water of the suspected wife, and You cannot falsify Your law, which says, “She shall be unharmed and shall retain seed” (Num. 5:28)

On a literal level, Numbers 5:28 promises conception for the barren wife cleared of a charge of adultery. However, considerable social uproar would result from barren wives pretending to be adulterous in order to be cleared so that they would subsequently conceive. The probable disappointment of many of their hopes would also call the law of Heaven into question. BT Berakhot 31b therefore reinterprets the Numbers ruling as follows: “No, it teaches that if she formerly bore with pain she now bears with ease, if she bore short children she now bears tall ones, if she bore swarthy ones she now bears fair ones, if she was destined to bear one she will now bear two.” This metaphorical exegesis of an inconvenient biblical reassurance obviated the potential anarchy that might have been occasioned by women taking their sexual destinies into their own hands. The potential for chaos would have been even greater if women were legally obligated to produce children.

Divorcing an Infertile Wife

Mishnah Yevamot 6:6 also rules that “If a man took a wife and lived with her for ten years and she bore no child, he may not abstain [any longer from the duty of propagation],” although exactly how he is to proceed in this instance is not spelled out. (Aramaic) A work containing a collection of tanna'itic beraitot, organized into a series of tractates each of which parallels a tractate of the Mishnah.Tosefta Yevamot 8:5, however, explicitly states that a man in this situation must divorce his wife and return her marriage settlement to her “For perhaps he did not merit being built up through her.” Since there is no proof that their infertility is the divorced wife’s fault, the Tosefta Yevamot 8:6 states that the divorced wife may marry again, “For perhaps she did not merit being built up through this man.” These measures are also recommended in BT Yevamot 65b, where the rabbis point out that a precedent for the practice of divorcing an infertile wife after ten years may be drawn from Genesis 16:3, since it was only after ten years of living in the land of Canaan that Sarai accepted her infertility and surrogated her servant to bear a child on her behalf. This passage goes on to say that “If the man or the woman was ill, or if both were in prison, [the years when they are separated] are not included in the number” of years after which a divorce is required. The assumption of infertility must follow ten years of normal marital relations.

Mishnah Yevamot 6:6 ruled that “If he divorced her, she is permitted to marry another and the second husband may also live with her [no more than] ten years [without offspring].” A childless woman who does not become pregnant during ten years of her second marriage is presumed to be barren and must once again be divorced. BT Yevamot 65a rules that she may marry again only if her third husband already has children from a previous union. Although the The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhah mandates divorce so that both partners may try again in new relationships, an unresolved discussion in BT Yevamot 65a indicates that some men in childless marriages chose to take a second wife rather than divorce an apparently infertile spouse. Conversely, BT Yevamot 65b records instances of wives who successfully petitioned rabbinic courts to compel their unwilling husbands to divorce them after ten years of infertile marriages. These requests were granted, not because women are obligated to have children, but because their pleas based on fears of an impoverished widowhood and old age without the support of offspring were persuasive to the court.

Rabbinic Aggadic Writings

The extent to which infertile marriages ended in divorce is impossible to determine but it is noteworthy that rabbinic aggadic writings generally deplore dissolution of marriages, even when male procreation is at stake. Many passages in the Statements that are not Scripturally dependent and that pertain to ethics, traditions and actions of the Rabbis; the non-legal (non-halakhic) material of the Talmud.aggadah present the childless marriage as a situation where human needs and feelings overrule legal prescriptions. In the case of a childless but otherwise happy couple, where significant human suffering would result from divorce, there is an acceptance that the obligation to reproduce is neither enforceable nor paramount.

Aggadic traditions about the infertility of the biblical matriarchs also express ambivalence about the option of divorce and stress the efficacy of prayer and the necessity of faith in God. The following homiletical tale from Pesikta de-Rab Kahana 22:2 teaches that infertility is never more than a presumption:

A man is under the obligation to fulfil the commandment, “Be fertile and increase” (Gen. 1:28) but a woman is under no such obligation. . . . In Sidon it happened that a man took a wife with whom he lived for ten years and she bore him no children. When they came to R. Simeon bar Yohai to be divorced, the man said to his wife: “Take any precious object I have in my house—take it and go back to your father’s house.” Thereupon, R. Simeon bar Yohai said: “Even as you were wed with food and drink [being served], so you are not to separate save with food and drink [being served].” What did the wife do? She prepared a great feast, gave her husband too much to drink [so that he fell asleep], then beckoned to her menservants and maidservants saying, “Take him to my father’s house.” At midnight he woke up from his sleep and asked, “Where am I?” She replied, “Did you not say, ‘Whatever precious object I have in my house—take it and go back to your father’s house?’ I have no object more precious than you.” When Simeon bar Yohai heard what the wife had done, he prayed on the couple’s behalf, and they were remembered with children. For, even as the Holy One remembers barren women, righteous men also have the power to remember barren women.

Among the striking aspects of this vivid story are its anti-nomian slant and its subversive tendencies. The husband is only trying to obey the law that he is obligated to fulfil, even though that means dissolving a happy union. His wife, who is not so obligated, is free to maneuver events behind the scenes to preserve her marriage. She does so by using deceptive stratagems that succeed in convincing those around her that she is in the right. A great rabbi prays for the woman and her husband who are now reunited, and they are ultimately blessed with children. Hope is offered to all who hear or read this story that infertility is never a certainty, that intercession is possible through prayer, and that devoted human relationships have a meaning that transcends halakhic demands. Both Pesikta de-Rab Kahana 22:2 and a version of this aggadic tale found in Song of Songs Rabbah 1:4 §2 end the story with a consolation text offering future comfort to all who depend on God. The following is the ending found in Song of Songs Rabbah:

And is not the lesson clear: If a woman, on saying to a mere mortal like herself, “There is nothing I care for more in the world than you,” was visited, does it not stand to reason that Israel who wait for the salvation of God every day and say “We care for nothing in the world but You,” will certainly be visited? Hence it is written: “Let us delight and rejoice in Your love” (Song of Songs 1:4).

A Barren Wife’s Shame & Suffering

Not all infertile marriages were resolved so happily and the rabbis fully acknowledged the suffering that results from childlessness. Even if the barren wife has no religious obligation to fulfill, she has failed to fulfill the primary expectation of her societal role, and as Genesis Rabbah 71:5 remarks, in the name of R. Ammi bar Nathan, it is children who assure a wife’s position in her home. The importance of offspring in securing a woman’s status, as well as the divine role in facilitating fertility, is elucidated in Genesis Rabbah 71:1:

“The Lord saw that Leah was unloved and He opened her womb” (Gen. 29:31). “For the Lord listens to the needy,/ and does not spurn His captives” (Psalm 69:34). . . . “And does not spurn His captives” alludes to childless women who are as prisoners in their houses, but as soon as the Holy One, blessed be He, visits them with children, they become erect [with pride]. The proof is that Leah was unloved in her house, yet when God visited her she became erect; hence it is written, “The Lord saw that Leah was unloved and he opened her womb.”

As this passage compassionately delineates, the barren wife endured shame and reproach for disappointing her husband at home and in the eyes of the world. Pesikta Rabbati 42:5 alludes to the “governors and governors’ wives who for so long jeered at Sarah, calling her ‘barren woman,’” and the same text at 43:8 describes the way the childless Hannah was mocked by her co-wife, Peninnah:

Peninnah would vex Hannah with one provocation after another. What would Peninnah do? According to R. Nahman bar Abba, Peninnah would get up early and say to Hannah: “Why don’t you rouse yourself and wash your children’s faces, so they are fit to go to their schoolmaster?” And at twelve o’clock, she would say: “Why don’t you rouse yourself and welcome your children who are about to return from school?” Such is the provocation referred to in the words, “Moreover, her rival, to make her miserable, would taunt her that the Lord had closed her womb” (1 Samuel 1:6).

Similarly, referring to the derision and sarcasm suffered by the childless wife as a present reality, Genesis Rabbah73:5 interprets, “Now God remembered Rachel; God heeded her and opened her womb. She conceived and bore a son, and said, ‘God has taken away my disgrace’”(Gen. 30:22–23) as follows: “R. Levi b. Zechariah said: Before a woman has given birth, any misdeed is attributed to her. After she gives birth all the blame is on her son—‘Who ate this thing—your son! Who broke this article—your son!’” As these sarcastic remarks reveal, the rabbis recognized the unfortunate situation of the barren woman.

Barren Matriarchs

Rabbinic exegetes were aware of the theme of apparent infertility in a number of biblical narratives having to do with matriarchs and the mothers of great leaders such as Samuel. A strong exegetical tradition, intended to console as well as to explain, addressed the question, “Why were the matriarchs barren?” The most meaningful responses to this question stressed the efficacy of prayer and the value of suffering that leads to purification and brings people closer to God, as in this passage from Genesis Rabbah 45:4:

Why were the matriarchs barren? R. Levi said in R. Shila’s name and R. Helbo in R. Johanan’s names: Because the Holy One, blessed be He, yearns for their prayers and supplications. Thus it is written, “O my dove, in the cranny of the rocks,/Hidden by the cliff” (Song of Songs 2:14): Why did I make you barren? In order that, “Let Me see your face,/Let me hear your voice” (Song of Songs 2:14).

Similarly, BT Yevamot 64a suggests that the matriarchs and patriarchs were initially childless “because the Holy One, blessed be He, longs to hear the prayer of the righteous.”

Other reasons for the infertility of the matriarchs are offered in the remainder of Genesis Rabbah 45:4:

R. Azariah said in R. Hanina’s name: So that they might lean on their husbands despite their beauty. R. Huna and R. Jeremiah in the name of R. Hiyya b. Abba said: So that they might pass the greater parts of their life untrammeled. R. Huna, R. Idi, and R. Avin in R. Meir’s name said: So that their husbands might derive pleasure from them, for when a woman is with child she is disfigured and lacks grace. Thus, the whole ninety years that Sarah did not bear she was like a bride in her canopy.

Two of the explanations recorded in this text consider childlessness in terms of the mothers of Israel themselves. The first suggests that infertility was meant to humble the matriarchs, who are imagined as great beauties. Given women’s propensity for vanity and light mindedness, they might have behaved contemptuously to their husbands without the pain of childlessness to depress their spirits and render them dependent. The second explanation, conversely, explains childlessness as a benefit which allows a woman considerable freedom since she is not subject to the constant needs of her offspring. The matriarchs were spared such inconveniences until unusually late in their lives. Genesis Rabbah 45:4 concludes by suggesting that the matriarchs were infertile so that their husbands could enjoy their wives’ beauty unimpaired by the ravages of pregnancies and childbearing. No doubt some comfort is intended here, for as BT Yevamot 63b notes, “A beautiful wife is a joy to her husband; the number of his days shall be [as if] double.” A parallel passage in Song of Songs Rabbah 2:14 §8 adds at this point, that “as soon as Sarah conceived, her good looks faded,” as it is said, “In sadness [at the loss of beauty] you shall bring forth children” (Gen. 3:16).

More convincing are rabbinic explanations that connect fertility to the operation of divine providence and the unfolding covenantal narrative of the relationship between God and Israel. Biblical and rabbinic sources are convinced that conception is granted by the grace of God and this presumption informs a number of rabbinic remarks on the ultimate success of the matriarchs in conceiving and bearing children. BT Ta’anit 2a–b quotes R. Johanan as follows:

Three keys the Holy One, blessed be He, has retained in His own hands and not entrusted to the hand of any messenger: these are the key of rain, the key of childbirth, and the key of the revival of the Dead. . . . .The key [mafteah] of childbirth, for it is written, Now God remembered Rachel; God heeded her and opened her womb” (Gen. 30:22).

Similarly, Genesis Rabbah 45:2 explains “And Sarai said to Abram, ‘Look, the Lord has kept me from bearing” (Gen. 16:2) as follows: “Said she, I know the source of my affliction: It is not as people say [of a barren woman], ‘She needs an amulet, she needs a charm,’ but ‘Look, the Lord has kept me from bearing.’”

Sarah is said to reject the talismans and spells of popular religion because she knows that it is God who can open the womb whenever He wills it. The aggadic tradition attaches a number of seemingly miraculous elements to this conviction of divine intercession in human conception. BT Yevamot 64a–b relates that prayer reversed not only the infertility of Abraham and Sarah but prompted God to transform their actual physical forms to make conception possible because originally each was of doubtful sex (tumtumim). In the same passage, R. Nahman is said to have stated in the name of Rabbah ben Avuha that prior to God’s response to her entreaties: “Our mother Sarah was incapable of procreation; for it is said, ‘Now Sarai was barren, she had no child’ (Gen. 11:30); [this means] she had not even a womb.”

God and Fertility: The Efficacy of Prayer

In these passages, God’s primary role in fertility is again emphasized. Men may be like God in their ability to generate new life, but the similarity has its limits. Men may plant their seed but only God can open the womb and God does so according to a divine calculus beyond human understanding. The only way in which humans can play a role in the process is through prayer.

The childless matriarchs provided an important model of the efficacy of prayer and they also became important metaphors for consolation and comfort. Over time rabbinic enumerations of infertile biblical women whose prayers were answered evolved. Based on an alternate reading of Hannah’s invocation to God in 1 Samuel 2:5, “While the barren woman bears seven,” as “On seven occasions has the barren woman borne,” the seven barren women are said to include Sarah, Rebecca, Leah, Rachel, the wife of Manoah (Samson’s mother), and Hannah. The seventh is not an individual who lived in the past but is the personified Israel of some future time, based on Second Isaiah’s characterization of Zion as a barren woman: “Shout, O barren one,/You who bore no child!/Shout aloud for joy,/You who did not travail!/For the children of the wife forlorn/Shall outnumber those of the espoused/—said the Lord” (Isaiah 54:1).

A typical example of such an enumeration appears in the homiletical A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).midrash collection Pesikta de-Rav Kahana20.1. The first section of a sermon based on Isaiah 54:1, “Shout O barren one,” begins:

“He sets the childless woman (akarah) among her household/As a happy mother of children (banim)” (Psalm 113:9). There were seven such barren women: Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, Leah, Manoah’s wife, Hannah, and Zion. Hence the words “He sets the childless woman (akarah) among her household” apply to Sarah [since we read] “Now Sarai was barren (akarah)” (Gen. 11:30), but the words “As a happy mother of children (banim) also apply to our mother Sarah: “Sarah suckled children (banim)”(Gen. 21:7).

The passage continues with a consideration of the remaining five biblical barren wives; in each instance biblical prooftexts demonstrate both her initial infertile status as an akarah and her ultimate triumph as a mother of children (banim). Peskita de-Rav Kahana 20:1 concludes with references to the future of Zion:

Finally, the words, “He sets the childless woman among her household” apply to Zion [of whom it is said]: “Shout, O barren one,/ You who bore no child!” (Isaiah 54:1); so [too] do the words “As a happy mother of children” [as it says] in, “And you will say to yourself,/ ‘Who bore me these for me/ When I was bereaved and barren,/ Exiled and disdained’” (Isaiah 49:21).

In this and similar homilies, the repeated fulfillment of the prayers of the childless point to the ultimate restoration and flowering of the nation and land of Israel. In rabbinic society infertility was not an affliction exclusive to women. Childless men were painfully aware of having failed to fulfill a religious obligation. Still, the models of the barren matriarchs, and the accounts of divine responsiveness to their individual supplications, must have had singular and empowering resonances for women, whose participation in prayer, at least in public, was neither facilitated by education nor sanctioned by communal norms. The gleefulness with which the vindication of such suffering wives as Sarah is recounted seems proof of a popular female piety which cherished the recollection of biblical women who could communicate so effectively with God. The matriarch’s answered entreaties and redemption from abasement, as well as their frequent linkage to the happy and fecund future of Zion, must have provided spiritual sustenance to women in a society which limited their access to most avenues of religious affirmation.

Baskin, Judith R. Midrashic Women: Formations of the Feminine in Rabbinic Literature. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2002.

Baskin, Judith. “Rabbinic Reflections on the Barren Wife.” Harvard Theological Review 82 (1989): 1–14.

Biale, Rachel. Women and Jewish Law. New York: Schocken, 1984.

Callaway, Mary. “Sing, O Barren One”: A Study in Comparative Midrash. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1986.

Cohen, Jeremy. “Be Fertile and Increase, Fill the Earth and Master It.” The Ancient and Medieval Career of a Biblical Verse. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1989.

Feldman, David M. Marital Relations, Birth Control and Abortion in Jewish Law. New York: New York University Press, 1968.

Hauptman, Judith. Rereading the Rabbis: A Woman’s Voice. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1998.

Patai, Raphael. “Jewish Folk-cures for Barrenness.” Folklore 54 (1943):117–24 and 56 (1945): 208–18.

Weisberg, Dvora. “Men Imagining Women Imagining God: Gender Issues in Classic Midrash.” In Agendas for the Study of Midrash in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Marc Lee Raphael. Williamsburg, VA: Department of Religion, College of William and Mary, 1999, 63–83.