Matriarchs: A Liturgical and Theological Category

Among egalitarian religious congregations throughout the world, the most popular addition to the traditional liturgy is the mention of the Matriarchs in birkat avot (the blessing of the ancestors), the opening blessing of the Amidah. This addition derives from a broadened theology that aspires to enshrine the encounter between the matriarchs and YHWH in the Jewish national memory. The addition of the Matriarchs to birkat avot may be seen as a continuation of a later midrash that Israel was saved from Egypt by the merit of the Matriarchs.

Origins

Among egalitarian religious congregations throughout the world, the most popular addition to the traditional liturgy is the mention of the Matriarchs in birkat avot (the blessing of the ancestors), the opening blessing of the Lit. "standing." The primary element of each of the three daily prayer services.Amidah:

Praised are You, Adonai our God and God of our ancestors, God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob [Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah], great, mighty, awesome, exalted God who bestows lovingkindness, Creator of all. You remember the pious deeds of our ancestors and will send a redeemer to their children's children because of Your loving nature.

This addition derives from a broadened theology that aspires to enshrine the encounter between the matriarchs and YHWH in the Jewish national memory as this finds expression in the liturgy. The phrase “Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah” originates in a Lit. (Aramaic) "outside." Halakhah and aggadah from the tanna'ic period that was not included in Judah ha-Nasi's Mishnah.baraita that reflects the ancient stratum of the sages’ philosophy: “The term ‘patriarchs’ is applied only to three, and the term ‘matriarchs’ only to four” (BT Berakhot 16b). The following saying, which clarifies how the sages interpreted the term “four Matriarchs,” occurs three times in the The discussions and elaborations by the amora'im of Babylon on the Mishnah between early 3rd and late 5th c. C.E.; it is the foundation of Jewish Law and has halakhic supremacy over the Jerusalem Talmud.Babylonian Talmud (Nazirite; person who vows to abstain for a specific period (or for life) from grape and grape products, cutting his hair, and touching a corpse.Nazir 23b, Sanhedrin 105b and Horayot 10b):

Blessed above women shall Jael be, the wife of Heber the Kenite. Above women in the tent shall she be blessed, and by “women in the tent,” Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah are meant.

Merit of the Matriarchs

This Talmudic expression found its way into the blessing for daughters on the eve of the Sabbath: “May God make you like Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah.” Along with this tradition, there is also an apparently later midrashic tradition that the nation of Israel had six matriarchs: “Six corresponding to the six matriarchs: Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, Leah, Bilhah and Zilpah” (Pesikta de-Rav Kahana 1:7, “And the tribal heads approached”; also Song of Songs Rabbah 6: “You are beautiful”; Esther Rabbah 1:12, “On the throne”). The liturgical wording “Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah” was based on Rashi’s commentary on a baraita in BT Berakhot 16b: “There are only three Patriarchs of Israel, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob … and only four Matriarchs, Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah.” The addition of the Matriarchs to birkat avot in the Amidah may be seen as a continuation of a later A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).midrash that Israel was saved from Egypt by the merit of the Matriarchs (and not that of the Patriarchs):

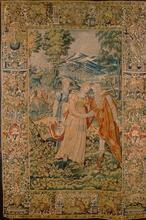

The Holy One, blessed be He, rescued Israel from Egypt only because of Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah: as a reward for Sarah’s taking hold of Hagar and bringing her to Abraham’s bed; for Rebecca’s saying “I will go” when asked, “Will you go with this man?” (Genesis 24:58), putting her trust in her Father in Heaven; as a reward for Rachel’s taking hold of Bilhah and bringing her to Jacob’s bed; as a reward for Leah’s taking hold of Zilpah and bringing her to Jacob’s bed. Therefore the Holy One, blessed be He, rescued Israel from Egypt, because of the deeds of Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah. Therefore, it is said: “God restores the lonely to their homes” (Psalms 68:6 (Lit. "order." The regimen of rituals, songs and textual readings performed in a specific order on the first two nights (in Israel, on the first night) of Passover.Seder Eliyahu Rabbah 25, “Blessed is He, blessed is His name”).

If so, then what, in the sages’ opinion, is the merit of the Matriarchs which brought the redemption upon the people of Israel? The midrash from Seder Eliyahu Rabbah replies that it was their insistence on the continuity of family, which is the basis of the nation, and their demonstration of complete faith in God even in the face of hardship: each woman’s barrenness; natural, human jealousy— Sarah’s of Hagar and Rachel’s and Leah’s of each other; Rebecca’s risk in marrying a stranger and of going to live in the foreign land of Canaan, not her native land—the latter being a risk they all took. Their coping with these painful hardships was considered a deed of hesed (lovingkindness). Deeds of hesed, the subject of birkat avot in the Amidah, are deeds done for others, which the Matriarchs themselves performed beyond the required extent (Moses ben Maimon (Rambam), b. Spain, 1138Rambam, Guide to the Perplexed, 3:53). These acts of hesed, which the midrash in Lit. (from Aramaic teni) "to hand down orally," "study," "teach." A scholar quoted in the Mishnah or of the Mishnaic era, i.e., during the first two centuries of the Common Era. In the chain of tradition, they were followed by the amora'im.Tanna d’ve Eliyahu Rabbah calls “the acts of Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah,” brought the revelation of God to their sons and daughters in the great miracle of the redemption from Egypt. The mention of the Matriarchs’ merit and their hesed takes on even greater significance in our generation, in which the female descendants of the Matriarchs are enriching the Jewish people with their public religious leadership and modes of commentary. For the first time in Jewish history, these women are expressing their feminine religious experiences, which are rooted in the everyday reality of the female body, child care, family and homemaking. From the point of view of feminist interpretation and philosophy, the varied encounters with Yhwh in the midst of this reality are perceived as complementing the religious reality of the study hall and the synagogue, and thus, in our generation, they warrant mention in the Amidah liturgy.

Harlow, Jules, ed. Siddur Sim Shalom for Shabbat and Festivals. New York: 1998:3b, 35b, 115b, 156b, 234.

Teutch, David. Kol Haneshamah: Shabbat Eve (editor of Hebrew Text: Rabbi Arthur Green). Wyncote, PA: 1989: 98–99.

Orenstein, Debra. “Matriarchs and Patriarchs.” In Etz Hayim: Torah and Commentary, edited by David Lieber, 1359–1365. New York: 2001.

Ruddick, Sara. Maternal Thinking: Toward a Politics of Peace. Boston: 1989.