Rachel: Bible

The younger daughter of Laban and the wife of Jacob, Rachel is the mother of Joseph and Benjamin, who become two of the twelve tribes of Israel (Gen 35:24; 46:15–18). She spends much of her married life attempting to bear children for Jacob and eventually uses her maid Bilhah as a surrogate, but Rachel still craves biological children. She and her sister Leah, also Jacob’s wife, conspire so they both may have children with him, leading to the birth of Rachel’s son Joseph. Soon after, Rachel dies giving birth to her second son; her early death makes her an image of tragic womanhood. After the biblical period, “Mother Rachel” continued to be celebrated as a powerful intercessor for the people of Israel.

Marriage

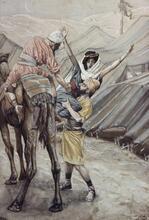

When Jacob goes to Mesopotamia to find a wife from his mother’s family (the line of Terah), he meets the shepherd Rachel at a well. He waters her flock, kisses her, and announces their kinship, for Jacob is both Laban’s nephew (through his mother Rebekah) and his second cousin (through his father). Rachel runs home to tell of his presence, and Laban invites Jacob to the house (Gen 29:9–14). Jacob loves Rachel and arranges to marry her and to work seven years as her bride wealth. At the wedding, however, Laban substitutes Leah, his older daughter, for Rachel. Explaining that it was not the custom to give the younger in marriage first, he promises Rachel to Jacob at the end of the week of the wedding feast, on the proviso that Jacob work another seven years to pay off a second bride price (Gen 29:15–30).

Like Sarah and Rebekah before her, Rachel experiences a long period of barrenness. The infertility of the matriarchs has two effects: it heightens the drama of the birth of the eventual son, marking Isaac, Jacob, and Joseph as special; and it emphasizes that pregnancy is an act of God. For when God “saw that Leah was unloved, he opened her womb” (Gen 29:31), giving Leah four sons (Gen 29:32–35). Rachel, envious of her sister, forcefully demands children from Jacob: “Give me children or I shall die!” (Gen 30:1). Jacob is incensed, declaring that he can do nothing because it is God who has denied Rachel children (Gen 30:2). As a consequence of her demand, Jacob agrees to her plan, to give Bilhah, whom her father had given her (Gen 29:29), to Jacob as a wife.

Efforts to Bear Children

Jacob already has children, but Rachel herself wishes to acquire children through her surrogate (as does Bilhah). The plan works, and Rachel names the child Dan, explaining “God judged [that is, vindicated] me” (Gen 30:5–6). Still competing with her sister, Rachel has Bilhah bear another son, whom she names Naphtali (meaning “I have prevailed”), in reference to the “contest” with her sister that she has been waging and winning (Gen 30:7–8).

The competition between the sisters/co-wives continues as Leah gives her maid Zilpah in turn. Despite the birth of children to these surrogates, Rachel and Leah still want to conceive their own. A turning point comes when Leah’s son Reuben finds mandrakes. A mandrake root, which looks like a newborn baby, was often considered a fertility charm and an aphrodisiac. Rachel wants the mandrakes, and she has something that Leah wants even more than mandrakes. She has occupancy of Jacob’s bed and trades a night with Jacob for the mandrakes. When they reach an agreement, Leah announces to Jacob that she has “hired” him (Gen 30:14–16). Co-wives are normally rivals, which is perhaps why biblical law forbids a man from marrying sisters (Lev 18:18). But when the co-wives cooperate, Jacob, like other husbands, complies with their wishes.

This agreement proves fruitful for both wives. Leah bears three more children; finally, after eleven children have been born to Jacob, Rachel bears a son and names him Joseph (“he adds”). Her two explanations for the name reveal her state of mind: “God has taken away my reproach” and “may the Lord add to me another son!” (Gen 30:22–24). In the very moment of relief and joy, she is not satisfied: she wants more. Rachel, like Jacob, is simply not content with what is given her. Her lack of satisfaction becomes clear when the family leaves Laban and sets out for the land of Canaan. Like Rebekah before them, both sisters actively agree to leave for Canaan. At the same time, they both express their anger at Laban, who never gave them any of the bride wealth earned by Jacob’s fourteen years of service for them (Gen 31:14–16).

Plan to Trick Jacob

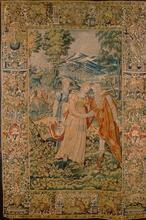

But Rachel alone takes action: she steals her father’s teraphim, his household gods (Gen 31:19). Her behavior often bears a shadowy resemblance to Jacob’s. Jacob supplanted his elder sibling, but Rachel didn’t succeed in supplanting hers at marriage. Jacob had received Esau’s birthright; Rachel takes the teraphim, which may have had something to do with property rights, perhaps to secure some inheritance. Or they may have been primarily religious images, intended to invoke the protection of the ancestors. In either case, possession of the teraphim was the prerogative of the head of household. Laban would never have given them to her, and he comes looking for them.

Unaware of what Rachel has done, Jacob takes an oath that “anyone with whom you find your gods will not live” (Gen 31:32). The reader knows what Jacob does not—that Rachel has taken the gods and is now in danger, not only from her father, but also from the oath. Laban must not find the gods; Rachel, a trickster like her father, her aunt (Rebekah), and her husband, thinks of a stratagem. She places the gods under her seat and declines to rise because she is menstruating (Gen 31:33–35). Her womanhood perhaps disqualifies her from receiving the teraphim legitimately, so she uses her womanhood to prevent Laban from taking them away once she has taken them illegitimately.

In the end, Rachel’s stratagem comes to naught. She could not keep the teraphim, for Jacob commands his household to bury (NRSV, “put away”) all their foreign gods, which almost certainly would include these teraphim (Gen 35:2). More tragically, in a sad irony, the very womanhood that has helped her trick Laban thwarts her daring and her ambition in a way that has plagued women through the ages. Finally fertile, she dies bearing her second child, Benjamin. Jacob buries her where she died, in her own tomb (Gen 35:20; 48:17) and not in the ancestral tomb at Machpelah.

Legacy

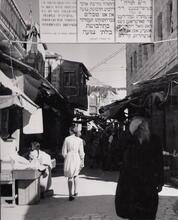

There is one more twist to the story. Rachel, who died young, becomes an image of tragic womanhood. Her tomb remained as a landmark (see 1 Sam 10:2) and a testimony to her. She and Leah were remembered as the two “who together built up the house of Israel” (Ruth 4:11). Rachel was the ancestress of the Northern Kingdom, which was called Ephraim after Joseph’s son. After Ephraim and Benjamin were exiled by the Assyrians, Rachel was remembered as the classic mother who mourns and intercedes for her children.

More than a hundred years after the exile of the North, Jeremiah had a vision of Rachel still mourning, still grieving for her lost children. Moreover, he realized that her mourning served as an effective intercession, for God promised to reward her efforts and return her children (Jer 31:15–21). After the biblical period, “Mother Rachel” continued to be celebrated as a powerful intercessor for the people of Israel.

Greenberg, Moshe. “Another Look at Rachel’s Theft of the Teraphim.” Journal of Biblical Literature 81 (1962): 239–248.

Meyers, Carol, General Editor. Women in Scripture. New York: 2000.

Niditch, Susan. Underdogs and Tricksters: A Prelude to Biblical Folklore. San Francisco: 1987.

Pardes, Ilana. Countertraditions in the Bible: A Feminist Approach. Cambridge, MA: 1992.

Spanier, Ktziah. “Rachel’s Theft of the Teraphim: Her Struggle for Family Primacy [Gen 31].” Vetus Testamentum 42 (1992): 404–412.

van der Toorn, Karel. “The Nature of the Biblical Teraphim in the Light of the Cuneiform Evidence.” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 52 (1990): 203–222.