Hagar: Bible

Hagar is Sarah’s Egyptian slave woman whom Sarah gives to Abraham as secondary wife and who would bear a child for him. This practice of surrogacy can be found in a number of ancient Near Eastern texts. After Hagar becomes pregnant, Sarah treats her harshly, and eventually Hagar flees from her mistress into the wilderness where God’s messenger speaks to her. She is the only character in the Bible who gives God a name based on her experience with the Divine. Although the Qur’an does not tell Hagar’s story, a collection of the words of the prophet Muhammed extol Hagar (Hajar). Hagar has long represented the plight of the foreigner, the slave, and the sexually abused woman.

The Slave as Surrogate

Hagar is Sarai’s Egyptian slave woman, whom Sarai (later Sarah) gives to Abram (later Abraham) as a wife who would bear a child that would be considered Sarai’s (Gen 16:3). Although it bears a resemblance to modern technological surrogate motherhood, this custom may seem bizarre. However, cuneiform texts of the second and first millennia BCE attest to this custom in ancient Mesopotamia.

The first such text, from the Old Assyrian colony in Anatolia, dates from around 1900 BCE. A marriage contract, it stipulates that if the wife does not give birth in two years, she will purchase a slave woman for the husband. The most famous text, in the Code of Hammurabi (no. 146), concerns the marriage of a naditu, a priestess, attached to a temple, who is not allowed to bear children. Her husband has the right to take a second wife, but if she wishes to forestall this, she can give her husband a slave. In the world of the ancient Near East, a slave woman could be seen as an incubator, a kind of womb-with-legs.

Sarai and Abram see Hagar in this role and never call her by name. Hagar, however, sees herself as a person and, once pregnant, does not consider Sarai a superior; “she looked with contempt on her mistress” (Gen 16:4). Sarai, in turn, “abuses her” (Gen 16:6; NRSV, “dealt harshly with her”). The Hammurabi laws acknowledge the possibility that the pregnant slave woman might claim equality with her mistress, and they allow the mistress to treat her as an ordinary slave (law 146). This may be what Sarai is doing. However, Hagar is not passive.

Hagar’s Encounter With God

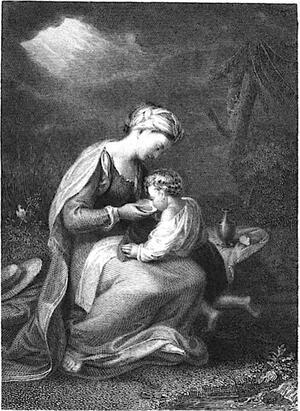

Rather than submit, Hagar runs away to the wilderness of Shur, where she meets God’s messenger, who tells her to return to submit to Sarai’s abuse for then she will bear a son who will be a “wild ass of a man” (Gen 16:12). Just as the wild ass was never domesticated, so too Hagar’s son would never be subject to anyone, and would live “with his hand against everyone” and “in everyone’s face” (Gen 16:12).

In this encounter with God’s messenger, Hagar realizes that she is actually speaking with God, and she gives God a name, El Roi, “The God who sees me.” Hagar is the only person in the Hebrew Bible who gives God a name (Gen 16:13).

The angel’s annunciation to Hagar is similar to announcements to Hannah, to the mother of Samuel, and to Mary the mother of Jesus: all would have children with special destinies, and all are addressed personally, not through their husbands. God’s request that Hagar become a slave again and return to be degraded by Sarai seems strange: why should God respect property rights over the freedom of persons? This is particularly odd considering the legal code of Israel, which, alone among ancient law systems, specified that runaway slaves should not be returned to their masters (Deut 23:16). But the angel’s speech here parallels God’s speech to Abram in Gen 15:13, which states that his children would be enslaved and degraded before their redemption. Both passages use the key terms that Israel uses to describe the Egypt experience. Hagar, the slave from Egypt, foreshadows Israel, the future slaves in Egypt. Her very name, Hagar, could be heard as hagger, meaning “the alien”; Hagar is an alien in Abram’s household as Israel will be aliens, gerim, in a foreign land. Hagar is to be degraded as Abram’s descendants will be degraded, and YHWH has “given heed to affliction” as God will hear the affliction of Abram’s descendants.

Hagar returns to Sarai and bears a son, whom Abram names Ishmael. Hagar and Ishmael are freed at Sarai’s instigation (Gen 21:9–14). Here too their destiny is parallel to later Israel’s, for the newly freed slaves head to the desert and struggle with thirst. God then saves the dying Ishmael, not because of Hagar’s cries or God’s promises to Abram, but because God heard Ishmael’s voice (Gen 21:15–21). God's relationship with Hagar is resealed with her son, as God’s relationship with Abram is resealed with Isaac and his son Jacob.

Like Jacob, Ishmael has twelve sons. Hagar is the ancestor of these twelve tribes of Ishmael (Gen 25:12–15). She may also be the ancestor of the Hagrites, tent dwellers mentioned along with Ishmaelites in Ps 83:7 (see also 1 Chr 5:10; 27:30).

Hagar in the Qur’an

The Qur’an does not tell the story of Hagar, but the Hadith (collections of the words of the Prophet Muhammed) give her the name Hajar, which may mean “splendid” or “nourishing.” In this version of the narrative, Sarai is explicitly jealous of Hajar and Ibrahim (Abraham) and accompanies Hajar into the wilderness.

Hagar has long represented the plight of a foreigner, a slave, and a sexually abused woman. She has been the focal point for oppressed peoples. Her story resonates with sexual abuse survivors, the poor and vulnerable, and in the past half century with African American women. While race is not a meaningful term for the biblical period, Hagar’s identity as an Egyptian woman has led some interpreters to see Hagar as African and dark-skinned. Some readers see in the relationship between Sarai and Hagar the story of the white female oppressor and the black slave woman.

Frymer-Kensky, Tikva. “Patriarchal Family Relationships and Near Eastern Law.” Biblical Archaeologist 44 (1981): 209–214.

Frymer-Kensky, Tikva. Rereading the Women of the Bible: A New Interpretation of Their Stories. New York: Schocken, 2002.

Gafney, Wilda C. Womanist Midrash: A Reintroduction to the Women of the Torah and the Throne. Louisville: Westminister John Knox: 2017.

Gossai, Hemchand. Power and Marginality in the Abraham Narrative. Lanham, MD: University Press of America: 1995.