Haskalah Attitudes Toward Women

The Haskalah was an experimental, internal protest movement of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that tried to effect transformation of Jewish life by convincing the Jews of the idea of modernity and the need to respond to its challenges through education and literature. But adherents, almost entirely men, were worried by what they perceived as a loss of control over the modernization process. Would the alternative to the weakening of traditional elements of Jewish life be linguistic, social, and cultural assimilation and bourgeois European acculturation? In this context, women’s modes of modernization—education, careers, independence—were considered positive, because they broke from traditional patterns and authority, but also problematic, because they seemed to threaten the family, Hebrew culture, and the Jewish collective.

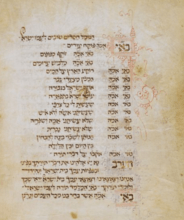

For the men of intellect who burst upon Ashkenazic Jewish society in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, starting a cultural revolution of Jewish Enlightenment; European movement during the 1770sHaskalah (enlightenment), the question of women’s status was the touchstone for the validity and consolidation of their innovative worldview. One of the outstanding proponents of the Haskalah was Judah Leib Gordon (1831–1892), who expressed the ambiguity of female/sing.: Member of the Haskalah movement.maskilim toward the “woman question.” Beginning in the 1870s, women Hebrew readers in the Jewish Pale of Settlement in Russia and women students in various cities in Europe considered him one of the few people who showed special sensitivity and empathy with regard to the difficult lives of Jewish women. His radical protest poem, “The Point of a Yod”—which opens with the words: “Hebrew woman, who knows your life? In darkness you came and in darkness you shall go. … A Jewish woman’s life is eternal servitude. … You shall be pregnant, give birth, suckle, wean, bake and cook and untimely wither”—was seen as expressing the cry of woman, at the mercy of hard-hearted rabbis, cut off from enlightenment and worldly pleasures. Some viewed it as a pioneering feminist manifesto (Gordon, 129–140).

Yet in one of Gordon’s last poems, he wrote a stinging satire mocking the character of the enlightened woman, many examples of whom could already be encountered in the urban communities of nineteenth-century Eastern Europe. “Oh, the learned woman has harmed me,” the poet laments. “I said: My life is better than that of my peers, now she shall be my resting place, the joy of my life—and I found, alas, pain and sorrow.” Her learning alters the gender hierarchy beyond recognition, infuses her with self-confidence, allows her to argue with her husband and even insist on her own point of view and, to her husband’s chagrin, reject his demands for sexual intimacy: “Tonight (I say it in a whisper) was a night for intimacy. I came to appease her, I called and there was no Biblically mandated fulfillment of a wife's sexual needs.onah [a play on words: “there was no answer” or “there was no sexual intimacy”], and when I said, ‘I desire sexual relations,’ she cried out, ‘No—I am nauseated.’” The disappointed husband regrets his bad bargain: “O erudite woman, quarrelsome woman, why did the Midianites not sell you?!” (Gordon, 329).

Women According to the European Enlightenment: Woman as Philosopher?

Intellectual women were a problem not only for Jewish enlightened men. Significant figures in the European enlightenment had already referred to their great difficulty in breaking with existing social norms and accepted gendered patterns of thinking. Women philosophers? Even the most liberal philosophers found it hard to accept what seemed an oxymoron. The most outspoken of them on this issue was Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778); despite his revolutionary and egalitarian approach to political regimes, in his book Emile (1762) he employed pseudo-scientific arguments to prove his claims of women’s social and intellectual inferiority. In his view, sex differences have their basis in natural law, and education must strengthen the perception of both sexes regarding their respective roles in society. While women’s education must not be neglected, it is nevertheless appropriate to teach them only that which will serve their destiny as faithful, submissive wives and devoted mothers.

The Prussian philosopher of Koenigsburg, Emmanuel Kant (1724–1804), denied women acceptance into the intellectual elite and portrayed learned women as deserving of ridicule since they bore characteristics contrary to those of “the fair sex.” Women were supposed to feel, not think intelligently. The opinion of his contemporary, the Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn (1729–1786), was not much different. When his fiancée Fromet Gugenheim (1737–1812) told him of the effort she was investing in her studies, he wrote her a letter in Yiddish expressing both disdain and concern for the reversal in the accepted gendered order of things: “You are greatly overdoing your diligence in reading. … What do you want to get out of it? Erudition? God save you from that! Moderate reading is proper for women, but not erudition. A young woman whose eyes are red from reading deserves to be mocked” (Mendelssohn 19:64).

The dispute in European enlightenment culture on the woman question showed how torn that culture was between its declared universalist, egalitarian tendencies and its difficulty in applying these absolute, lofty principles to social groups that were defined as “other” and discriminated against, such as poor people, slaves, Blacks, Jews and women. On the woman question, proponents of the old order based themselves on pseudo-scientific theories that provided a natural basis for women’s social inferiority and their exclusion from positions of power and prestige. There were even those who maintained that women’s brains were smaller and it was thus no wonder that they were incapable of philosophical discourse. Another justification cited the gendered division of labor into public and domestic spheres and the difference in economic functioning, given women’s emotional character, which naturally guided her to the warm, loving bosom of her home.

As the number of independent, intellectual and erudite women increased, the more was this perceived as a problem, arousing debate and causing a rift in the literary republic of the enlightened. By the end of the eighteenth century, Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797), a writer, journalist, and teacher from London, exposed the problematic nature and lack of consistency in the Enlightenment’s attitude to women. In England, France and Germany, both men and women participated in the struggle for women’s equal rights and for recognition of their intellectual ability to join the literary republic. But it is clear that Wollstonecraft’s book A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) was the Enlightenment’s most important feminist work. In it, she demanded nothing less than the application to women of all the revolutionary principles and values of the Enlightenment, such as equality, universalism, humanism, intellect and positive characteristics. None of these values, Wollstonecraft argued, was sex-dependent, nor could one set up a double, contradictory standard of values. Ethics and reason, she wrote, had no sexual identity. And in any case, who made the male the sole determiner of whether woman shared his gift of intellect? If women are also gifted with reason and ethical standards, then they must participate equally in intellectual life. Otherwise, the Enlightenment would lose its justification to be perceived as an advocate for a phenomenon with universal applicability. Indeed, this provocative work by Wollstonecraft, whom her opponents called “the philosophizing serpent,” not only raised the issue of women in the public sphere, but also established the topic as a touchstone for the entire Enlightenment movement.

Women According to the Haskalah Movement in the Eighteenth Century: The Bourgeois Ideal

Almost a hundred years were to pass before Wollstonecraft’s Jewish counterpart appeared, emphatically and publicly demanding women’s share in intellectual life and literature. But among those of the early proponents of the Enlightenment who pointed out the defects and flaws in contemporary Jewish society, there were some who criticized women’s place in Jewish culture. The most prominent of these was Isaac Wetzlar (1680?–1751) of Celle, whose Libes Briv (1749), which remained in manuscript form only, expressed his deep concern over the neglect of women’s education. With unusual sensitivity, his unique expository-ethical work pointed out the deliberate exclusion of women from elite scholarly culture, in which the vast majority of texts were in Hebrew, and their consequent propulsion towards Yiddish culture which, in the writer’s opinion, was inferior and distorted religious values. It was inconceivable that Hebrew, the Jews’ native tongue, should be inaccessible to young girls. How would they gain unmediated access to the Pentateuch, and how would they understand the prayers? Imagine the absurdity of a situation in which many young girls in the eighteenth century acquired European languages such as French and Italian, while Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah scholars, in their weakness and insensitivity, denied them access to the Hebrew language, thereby committing an intolerable desecration of the Divine Name. “I believe,” Wetzlar wrote, “that women have been gifted with the intelligence to pray to God, to praise and thank Him, exactly like men, and they need to know the meaning of their prayers. Many God-fearing women weep bitter tears because even as they stand in the synagogue and worship with the congregation, they do not understand what they are praying. They listen to the cantor read from the Torah but don’t understand what he is reading.” The Yiddish alternatives such as Ze’enah U-Re’enah were, in his opinion, bad literature and so remote from the source that they imparted misinformation and distorted values (Wetzlar, 92–96).

One might have anticipated that the Jewish Haskalah movement would encourage this critical trend, which brought about a cultural and social revolution in the 1780s and 1790s—a revolution which altered Ashkenazic Jewish intellectual discourse beyond recognition and brought the modern Jewish intellectual into the sphere of public opinion. The maskilim had sharp criticism for various aspects of Jewish life, especially its educational systems, priorities, rabbinic authority, intolerance, the world of Torah literature, attitudes toward European culture, economic activities and much else. Proponents of the Haskalah had internalized several of the Enlightenment’s basic values (humanism, rationalism, critical thinking, freedom, the importance of knowledge, and tolerance) and, with all the self-consciousness of the avant-garde that opened up a new and promising future, leaving behind the flawed past, they demanded a multidimensional transformation in consciousness and in social and cultural agendas. At the same time, the maskilim set up their own literary republic and invented the secular author, who ventured forth to public opinion without the backing of religious authority. The maskil’s literary work was mostly in Hebrew, related to scholarly religious texts and was packed with terms and associations from the heart of the religious world. Yet it was not added to the bookshelves of religious scholarship, and some of it was even subversive.

While the Haskalah movement itself crumbled in its important centers, Koenigsberg and Berlin, as early as the end of the eighteenth century, it had successors in various European countries, especially Galicia, Poland and Russia, throughout the nineteenth century. There, the maskilim continued to fulfill their culturally revolutionary task as agents of modernization and challengers of religious culture and the religious elite, including hasidism, which they attacked as the foe of enlightenment, the modern state and progress. The maskilim were the liberal and critical ideologues of Eastern European Judaism, planning reforms in that Judaism and creators of its public venue via literature and newspapers. This continued until the nineteenth century, when other ideological alternatives of modernization appeared, in the form of modern nationalism, Zionism and the cultural and class rebellion of socialism.

From its inception until almost its final years, the Haskalah was virtually an exclusively male movement. Those who launched the Enlightenment revolution of the eighteenth century were young men in their twenties and thirties who never imagined the possibility of women being in their ranks. Many maskilim earned their living as private tutors in the homes of the wealthy elite. They frequently formed deep friendships and romantic relationships there, but these connections did not render the girl a “maskilah” in her teacher’s eyes. The stereotypical character of woman as driven by emotion and desire, as opposed to the man who was guided by reason, did not allow him to see her as a candidate for joining the “covenant of the enlightened ones.” In addition, the distancing of Jewish women in the traditional milieu, their not being taught the religious texts which boys studied in school and their exclusion from institutions of higher Jewish learning all prevented them from acquiring a common cultural language with the maskilim. Hebrew, the language of the cultured religious elite, which was the focus of research and creativity during the Enlightenment, was not the language of women. Since they had not been exposed to Hebrew during childhood, they were unable to participate in literary and expository writing in that language, and only a few could read it. For young girls of wealthy families in Germany, German and French were the languages of literature and culture, part of the salon-bourgeois education they received and the profound acculturation to European tastes they acquired. The bourgeois ideal that destined women to the domestic roles of wife, homemaker, hostess and mother, left her no place in the public life that maskilic society wished to create. Moreover, some maskilim felt women were obstacles to the young female/sing.: Member of the Haskalah movement.maskil, threatening the male intellect and casting a net of inferior sexual temptations.

The sexual ethics of the maskilim were not very different from the traditional ones in moralistic works warning against “women’s sexual appetite,” spilling seed in vain and the sins of lust, which threatened transgressors with the punishments of hell. In guidance books for young men, Enlightenment teachers repeatedly warned against masturbation and erotic fantasies, which weakened the body and were obstacles to moral behavior. Adolescent boys were warned against the emotional and temptational threat of women and the danger of paralysis of their reason and their ability to develop in their studies. Women’s relegation to the field of sexual and domestic function prevented her from being perceived as a partner in intellectual dialogue. The Jewish maskilim in Germany adopted the bourgeois ideal of the “German housewife” who cultivates her modesty and morals and devotes herself to family and housework, which also became one of the values of the Haskalah even in its new centers in Eastern Europe during the nineteenth century. However, this did not mean that women’s education should be neglected. Various teachers praised those women who took the initiative to receive an education and some of them even set up the first organized learning frameworks for girls at the beginning of the century. But the goal of such bourgeois education was always the role of homemaker, wife and mother, with some added cultural polish necessary for the role of hostess.

The boundaries were very clear, and were stated explicitly in a short essay in the German-Jewish periodical Sulamit, in 1808. On the one hand, women were asked to abstain from harmful lowbrow culture, which expressed itself in romantic novels that attracted and aroused the imagination, and on the other hand they were warned not to become erudite. This phenomenon was already familiar and the author referred to it scornfully as being completely contrary to nature: “A woman who speaks and argues about abstract [philosophical] matters such as space and time, idealism and realism, or expresses an opinion about Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762–1814) or Friedrich Schelling (1775–1854), sounds utterly ridiculous.” Erudite women were just as despised as crude, ignorant women, whose world did not extend beyond the kitchen and pantry: “No enlightened person appreciates philosophy in a skirt, just as no one likes a stupid goose. The former is bad luck and a pest, while the latter is tasteless and boring” (Sulamit 1808: 69–70). The exclusion of women from the enlightenment revolution that the Jewish Haskalah brought about was almost total. Women were unrepresented in all the cultural struggles that agitated the public sphere, where liberal Jewish intellectuals, maskilim and subversives fought against the rabbinic cultural elite which increasingly became the orthodox guard of the walls of tradition.

Women According to the Haskalah Movement in the Nineteenth Century: The Boundaries of Modernization

If we are searching for the integration of women into the cultural awakening of the Jewish Haskalah and their entry into the public arena of internal Jewish discourse, we must turn to nineteenth-century Eastern Europe. The relatively slow and limited pace of modernization in Poland-Lithuania and Russia, the lower standard of living and the socio-cultural separation between the Jews and their environment did not allow for the same level of acculturation as served Jewish women of central and western European cities as their main pathway to modernization. The demographic concentration of Jews in Eastern Europe, the main center of European Jewry in the nineteenth century, led to especially intense religious and community life, comparable to that of the hasidic and yeshiva worlds. Until the second half of the century, Jewish cultural life consisted primarily of Hebrew culture, and the great internal argument aroused by the Haskalah movement maintained the high status of traditional texts. Women were excluded from this traditional culture and thus had no way of participating in the public sphere.

Unlike the Enlightenment revolution during the eighteenth century, which ended within a relatively short time, the significance of the Haskalah movement in Galicia and Russia was far greater. The maskilim were the internal critics of Jewish society, breaking the monopoly on culture and Hebrew literature which had hitherto been in the hands of the religious elite. Now they competed to be spokesmen and ideological leaders in public life. Thus, in a Jewish culture that valued the written word, the Haskalah movement was an agent of modernization of the first order. The maskilim led a series of cultural struggles against hasidism, its beliefs and its influence on the masses (beginning at the start of the century in Galicia), in favor of modern education (for example, the affair of governmentally driven Haskalah in Russia in the 1840s), in favor of making tradition meet the needs of modern life (the furor over religious reform in the 1860s) and against rabbinic control (for example, J. L. Gordon’s anticlerical campaign in the 1870s). The maskilim of the time had an opinion on almost every imaginable topic. As a result, they gradually rose to become the principal intellectuals, authors, journalists, editors, publicists, poets, novelists, and spokesmen for Eastern European Jewry in an era of change, leaving the rabbinical elite which opposed and feared these changes further and further behind.

Where were the women in all these social and cultural changes? Once again, just as in eighteenth-century Germany, the Jewish women of Eastern Europe were on different modernization tracks that bypassed the Haskalah. Alongside the continuation of traditional social and economic patterns of Polish and Lithuanian Jewry, in which many women supported their families as peddlers, storekeepers and merchants in the local markets, preserving the special model of devotion to religious values, customs and A biblical or rabbinic commandment; also, a good deed.mitzvot that women kept within their intimate home and family circle, there began processes of change that would have great significance.

In his critical work Sefer Ha-Mazref (The Crucible, 1868), Isaac Kovner (1840–?), a Lithuanian produce merchant and an eyewitness of keen perception, sketched the outlines of the new picture forming in the 1860s. More and more Jewish women were achieving economic independence, refusing to enter arranged marriages, and not allowing their parents to marry them off at a young age before they reached physical and economic maturity. Such a woman, Kovner wrote, “did not wish to remain at home and surrender to housework, awaiting her husband’s salary.” Young women in Eastern European cities, “young ladies of the new generation,” found work at stores, factories or shops, saved their money and sought their husbands with no interference from their families. The romantic ethos found a place among young people of this generation and with it not only marriage of choice at a relatively later age, but also religious permissiveness among working women of the lower class and women students of the middle and upper classes, many of whom became gymnasia pupils and students (Kovner, 206–214).

Haskalah literature such as the novel Ayit Zavua (The Hypocrite) by Abraham Mapu (1808–1867) or Fathers and Sons (1868) by Shalom Jacob Abramowitsch (Mendele Mokher Seforim, 1835–1917), the stories of Mordecai David Brandstaedter (1844–1928), and many contemporary accounts describe the increasing European acculturation of Jewish women during the second half of the nineteenth century. What had occurred in central and western Europe in the previous century now also began to impact on the largest Jewish centers in the world. Beginning with the reign of the Russian Tsar Alexander II (1855–1881), many phenomena encouraged the acceleration of acculturation. The development of cities, industrialization and railroad building, the success of wealthy Jewish entrepreneurs and industrialists, the extension of educational settings including girls’ schools, the opening of gymnasia and universities to Jews, the enticements of bourgeois life and the culture of fashion, theater, and music—all these contributed to the appearance of new types of Jewish women. Memoirs written by Eastern European women reflect the secularization process they underwent as they studied in the gymnasia or higher-education institutions in Russia or western Europe, their integration into the work force or migration from the provincial village to the lively metropolis.

Recently, Iris Parush has added another fascinating and significant element to the established list of factors through which modern European Jewish women blossomed—women’s exposure via literature to the multilingual modern cultural world (Parush, 2001). Women readers entered a unique historic “window of opportunity.” Their marginal position in the gender hierarchy and their exclusion from the public sphere of religion and Hebrew texts enabled them to devote themselves to reading freely and without supervision, especially belles lettres in Yiddish, German, French and Russian. Their exposure to European culture through reading novels and even radical Russian literature, and the ensuing legitimation of women’s reading, turned them into witting or unwitting agents of secularization and modernization. The women’s reading list was completely different from the men’s. They did not read the theoretical classics of the Enlightenment, from Moses Mendelssohn’s Biur Millot ha-Higayyon (the German translation of the Pentateuch, 1780–1783) to the Morei Nevukhei ha-Zeman (Guide of the Perplexed of the Time, 1851) by Nachman Krochmal (1785–1840); they took almost no part in the intellectual discourse of the Haskalah, did not, on the whole, undergo the cultural transformation that left its mark on the maskilic experience, and above all, were not part of the Haskalah’s literary republic, which was perhaps the major outcome of the maskilic revolution. When women read, they acculturated themselves to the European milieu, thus representing the development of the modern Jewish bourgeoisie, exactly as women learned to converse in foreign languages, played instruments, went to the theater, wished to dress according to Paris fashions and, in their walks along the city boulevards, displayed their European manners. When the male maskilim wrote, they were in fact waging a war against the rabbinic elite over the intellectual hegemony, in an attempt to revitalize the Jewish bookshelf and transform Jewish society and its culture.

The maskilim were amazed at women’s modes of modernization, had difficulty understanding them in their immediate context and were even critical of them, if not downright hostile. This led to ambivalence on the woman question in general. At one end of the spectrum of maskilic opinion were the radical maskilim, many of whom subscribed to the positivist and socialist theories of the Russian intelligentsia of the 1860s and 1870s. They saw the “woman question” as part of the emancipation of modern human society. Abramowitsch, for example, favored a woman’s right to choose her husband, receive an education and demand equal and respected status in society in the name of the universal values of equality (Abramowitsch, 1875), and Moses Leib Lilienblum (1843–1910), in a series of Hebrew newspaper essays, fought for women’s economic independence. Only the possibility of supporting themselves would free women from subjugation to their husbands, raise their status in society, improve their self-image, ensure that they would not have to depend on others and strengthen them at times of family crises (Lilienblum, Writings, 2:7–14).

Russian radicalism and its Jewish spokesmen posed a significant challenge to the maskilim. Through the press, the question of women’s equality, promoted by the radicals, became one of the subjects of public Haskalah discussion. Like Rousseau in the eighteenth century, Perez Smolenskin (1840 or 1842–1885), editor of Ha-Shahar, and Alexander Zederbaum (1816–1893), editor of Ha-Meliz, maintained that woman’s biological tasks rendered her demands for equality contrary to nature. It was impossible to grant women powers which nature had denied them (Zederbaum, 1878). “The curse of Eve” is on woman, Zederbaum wrote in the face of Lilienblum’s call for woman’s equality; she will never be free unless she chooses to deny her own nature, remaining unmarried and childless (Zederbaum, 1872). On the other hand, many maskilim showed real interest in women’s education. In their opinion, the question was not one of inferior social status which only a revolution could remedy, but of a problem that required treatment by improving and broadening the settings in which women could obtain knowledge and good values. When they suddenly became aware of the depth of women’s acculturation and the appearance on the scene of women students influenced by Russian radicalism, the attitude of the maskilim became critical and conservative. This was not the Haskalah we had hoped for, many essays declared. Young Russian-speaking women, reading French novels, dressed according to fashion, playing the piano, dancing at balls, parading ostentatiously along city boulevards, represented a “counterfeit Haskalah,” endangered the Jewish family, and constituted a potential for assimilation and conversion. Indeed, one must not neglect women’s education, but in the end they must function within the setting of home and family, the maskilim declared. If they do not, they will become an extremely dangerous secularizing element. Paradoxically, the same Haskalah revolutionaries, who were critics of society and envisioned Jewish modernization, were the ones who anxiously tried, in the case of modern Jewish women, to moderate and even limit their race toward modernization.

Researchers who have tried to understand the significance of the anxiety that characterized the Eastern European Haskalah proponents’ attitude toward women have proposed several explanations. The first of them was David Biale, whose book Eros and the Jews proposed a psycho-historical interpretation that relied mostly on a sensitive reading of several revealing autobiographies of Haskalah proponents, especially Aviezer (1864) by the Lithuanian maskil Mordecai Aaron Guenzburg (1795–1846). In his opinion, the adolescent traumas that future maskilim underwent prematurely, especially early sexual frustration, oppression by their mothers-in-law and their fear of sexually mature women, made them criticize traditional society and marriage patterns in general, and crystallize an alternative idea in the form of a bourgeois family and sexual modesty (Biale, 1992). Israel Bartal adopted this interpretation to a certain extent, but also added other elements drawn from the modern historical context. He emphasized the Haskalah proponents’ sexual frustration, which manifested itself in criticism of traditional society, which they blamed for their sexual weakness, mostly because of the early marriages imposed upon them. The maskilim aspired to restore male dominance. Their greatest fear was of an over-dominant woman, an image which, in their view, was supported by pseudo-scientific theories of women’s sexual appetites. But the maskilim also justified male supremacy in the family and society because they had internalized the hierarchical structure of the centralized class society whose focus was on sovereignty. They were also influenced by eighteenth-century German morality literature, which strengthened the German bourgeois model of the family and sexual morality. “It was not emancipation of women in the sense of equality of the sexes which was the social vision of the Eastern European maskilim,” Bartal summarized, “but rather putting the woman in her rightful place: her husband’s bed, the kitchen and house parties. The Eastern European maskil feared and trembled at the thought of a strong-willed woman with an uncontrollable sexual appetite” (Bartal, 1998).

For many, the process of joining the Haskalah undoubtedly involved a personal transition that shook them from one consciousness and literary space to another, causing both a crystallization of ideology and feelings of alienation, and sometimes hostility vis-à-vis traditional Jewish society. Often, this transition brought on a crisis characterized by displacement, wandering and separation from the family. One fascinating and especially touching example of this was Lilienblum’s relationship with his wife, as he described it in his book Hatte’ot Ne’urim (The Sins of Youth, 1876). When he became a maskil, he studied and wished to progress to higher learning, dreamed of a career and became a target for the Orthodox, who were angry that he had dared to publish his ideas on religious reform in the pages of Ha-Meliz. His wife remained behind, completely alien to his new world. He tried his luck as a maskil refugee in Odessa, on the shores of the Black Sea, one of the most modern Russian cities in the 1860s. “When we lived together, I found no common language with you,” Lilienblum wrote to his wife in a letter notifying her of his emotional separation from her. “The cultural gap between us has become a complete rift. Indeed, society is to blame, especially the Talmudic attitude to women: ‘How inferior the woman is to such despicable and base people!’ For them, women are men’s vessels, and in their opinion, ‘A reverent and awe-inspired Jewish man does not need a wife and companion but a chamber pot for waste fluid and a servant who will cook dinner for him and rock his ‘kaddishes’ [male children]” (Lilienblum, Writings, 2:370–373). In this sharp protest against rabbinic culture, Lilienblum represents the radical Haskalah. Like Solomon Maimon (1753–1800) eighty years earlier, he felt that the difference between cultured people and barbarians lay in their treatment of women. A man marries a woman, Lilienblum wrote with pain, so that she shall be a lifelong friend: “So that she will live in partnership with him and share his life, goals, ideas and feelings. In our case, that may no longer happen. Nothing can connect us, and so my ideal of marriage cannot be realized.”

But the maskilim were also suspicious of young girls who underwent acculturation and were members of the “new generation,” and did not necessarily accept them gladly. City girls seemed frivolous to them as is the case, for example, in the image of the girls of Odessa whom Reuben Asher Braudes (1851–1902) described in his novel Shetei ha-Kezavot (The Two Extremes, 1888): “I dwell in the city of Odessa, and my wife is one of the new generation for whom now is a time for laughing and dancing, who prefers the theater to the House of God, and banquets and dancing with a crowd of merrymakers to resting at ease in her home” (Braudes, 339). The daughters of a considerable number of maskilim were being trained as modern girls, receiving an education and professional training. Male and female tutors taught the daughters of Judah Leib Gordon. His eldest daughter “already hastens to speak and write in three languages: Russian, German and French, and all the other complementary studies customary among enlightened Jewish girls.” His youngest daughter attended the Russian gymnasia “according to a well-known program and will grow up in the big city among decent people who speak a clear language.” After a few years, the two women married, respectively, a Jewish lawyer and doctor.

The daughters of the radical maskil and socialist Dr. Isaac Kaminer (1834–1901) received a similar education, as did the daughter of the moderate maskil Abraham Baer Gottlober (1810–1899) (Feiner, The Modern Jewish Woman, 1998), who fought against the radicals. Yet women who wished to advance in their studies and careerist women ambitious to succeed in law or medicine were also seen as a worrisome phenomenon. “A woman of great intellect will neglect her home,” Mapu stated in concern. By doing so, he merely added his conservative opinion to that of the man considered the founding father of the Russian Haskalah, Isaac Baer Levinsohn (1788–1860), who in the 1860s wrote sharply against equality in education for women, saying that it could bring down the foundations of homemaking (Mapu, Letters, 185–189). Another especially interesting essay in Hebrew journalism, titled “What’s Happened to Our Sisters?,” warned against the assertiveness of “enlightened women,” and especially against women students who cried: “Let us go to St. Petersburg! Ours is the learning! Ours the sciences! We shall thrust aside our male colleagues and we shall be the doctors and the advocates in the land” (Maggid Mishneh, 1880).

The Haskalah was an experimental, internal protest movement that tried to effect a comprehensive transformation of Jewish life by convincing the Jews of the idea of modernity and the need to respond to its challenges through education and the written word: essays, stories, novels and poetry. Beginning in the 1860s and 1870s, maskilim of all hues in the ideological spectrum were worried by what they perceived as a loss of control over the modernization process. What was the vision for the new era that was coming into being? Would the alternative to the weakening rabbinic culture be a hedonistic life in the big city, with all its enticements? Would linguistic, social and cultural assimilation be the alternative? In this context, women’s modes of modernization were seen as positive because they broke the traditional patterns and the authority of those who by tradition had the power. Nevertheless, they were also viewed as problematic because in addition to threatening the family and certainly male identity, they also seemed to threaten Hebrew culture and Jewish collective continuity. In particular, theirs were seen as anti-nationalistic methods of modernization. For prominent maskilim such as Judah Leib Gordon, Lilienblum, Shmuel Joseph Fuenn (1818–1890), and especially Smolenskin, this was a source of profound concern. Was not the appearance of modern women evidence of their own failure to define the limits of Jewish modernization?

Women Attempt to Join the Haskalah Movement: Taube Segal

In light of all this, it is no wonder that when educated women who had acquired Hebrew knowledge, the entry ticket into the ranks of the maskilim, as well as some who had even internalized the values of the Haskalah and its vision, knocked on the doors of the Haskalah movement they were greeted with great surprise. Reactions were mixed: some criticized the entry of women into male territory and were concerned that the literary level would decline, while others welcomed it. Thus, for example, Lilienblum responded in 1868 to the book The Jews in England, translated by Miriam Markel-Mosessohn (1839–1920) from German to Hebrew: “You have removed from your sisters the shame of the misguided ones who prevent their daughters from learning an ancient tongue.” For him, she represented a positive alternative to frivolous modern women of the “new generation,” and he hoped that this would not be a unique phenomenon. “Your name will remain as a permanent memorial in Hebrew literature, for you are the first, and perhaps also the last, Jewish woman who has written a lucid and beneficial book!” (Lilienblum, 1869).

The new phenomenon of women authors reached maturity starting with the 1860s, when some of the women began to demand their right to an equal education and social recognition in the Haskalah movement’s public arena. In 1879, Mary Wollstonecraft’s Jewish counterpart made her appearance in Hebrew Enlightenment culture. The Galician periodical Ha-Ivri published, in several installments, an essay entitled “The Woman Question,” by Taube Segal, a Vilna woman of about twenty (Segal, 1879). This was the first feminist essay written in Hebrew, the work of a woman who declared a “women’s war” against the attempts to block their way to the heart of the Haskalah movement. There was no hope that the members of the “old generation” and the conservative Orthodox, who believed that “fortunate is he whose wife is not erudite” and zealously preserved women’s inferiority and ignorance would see the light and act for women’s benefit. Yet in a cynical and sharply critical style, she showed her readers the internal contradiction of the “new generation” of maskilim: that they favored the lofty values of freedom, equality and humanism with their enlightened slogans and rhetoric while treating women with scorn and discriminating against them, seeing the Haskalah as an exclusively male province. Could it be that “in these days of freedom and liberty, the daughters of Jacob should not know liberty and not breathe the air of freedom which they, too, desire and be able to study and work?” Could it be that “even in these days of elevated, lofty civilization, in our own time, men should regard the daughters of Zion as of little value and not human?” And why did the maskilim not make women’s education a major goal in their enlightenment project? When a woman who writes in Hebrew appears, people react with surprise to such a rare apparition, but that is only because enlightened men still maintain their prejudices and believe that women’s abilities are less than men’s: “Are we monkeys, have we no human understanding, that men should be so amazed to find anything excellent in us?” Women’s salvation would not come from the opinions of the maskilim, and so Segal saw a duty to inspire women with a fighting spirit: “I will overcome my fears and gird up my loins like a man to fight women’s battle with my poor pen.” If women could only obtain a suitable education and the recognition of their strength, and if women themselves understood that they must win their freedom and independence through learning a profession and beware lest men’s romantic advances and enticements numb their senses, they too could contribute to civilization, integrate into society and attain the emancipation they so desired.

When Judah Leib Gordon wrote the poem Ishah Melumdah (Erudite Woman, 1891 or 1892), one could regard it only as amusing satire and not as an expression of hostility that closed the gates of education to women. Gordon and his colleagues in the Haskalah movement knew very well that it was not only the fashionable city women or women who read foreign languages and were exposed to European culture that underwent the modernization processes of Jewish women, but also educated women who were involved as readers or writers in the modern culture that the maskilim had created. The turbulent nineteenth century, during which all the Jews in Europe coped with the challenges of modernity, also offered women Jewish education as one of the paths to modernization. The educated Jewish woman derived most of her values from the educated maskilim, but she always retained gender consciousness and sometimes, like Taube Segal, even burst out angrily against the maskilim for their discrimination against women, demanding that they address women’s equality with the terminology of enlightenment. Yet by the end of the nineteenth century, as this phenomenon became more familiar despite its relatively limited scope, significant reversals occurred in the ideological climate as well as in the areas of politics, demography and economics. The Haskalah movement reached its end for all practical purposes, making way for critical, post-maskilic ideas. The enlightened discourse of the Haskalah in Eastern Europe flowed mostly toward the new nationalist discourse, also incorporating the woman question. From then on, women who took part in Jewish public debate in Hebrew demanded an active role in the national movement and offered their help in nation-building—the project that gradually replaced the Enlightenment.

Primary Sources (in Hebrew)

Abramowitsch, S. J. (Mendele Mokher Seforim). What Are We? 6 (1875): 464–485; 526-534.

Braudes, Reuben Asher. Two Extremes. With introduction and notes by Ben-Ami Feingold. Jerusalem: Mosad Bialik, 1989.

Frischmann, David. Ha-Boker Or 6 (1881): 387–391.

Gordon, Judah Leib. Writings. Tel Aviv: Devir, 1964.

Gordon, Judah Leib. Letters. Edited by Yitzhak Weissberg. Warsaw: ha-aḥim Šuldberg, 1895.

Jashinowsky, Abraham. “What’s Happened to Our Sisters?” Maggid Mishneh 2 (1880): 153–154.

[J. Jeitteles]. Sulamit 2:1 (1808), 69–70.

Kant, Immanuel. “The Fair Sex.” In The Portable Enlightenment Reader, edited by Isaac Kramnic, 580–586. New York: Penguin, 1995.

Kovner, Yitzhak Isaac. Sefer ha-Mazref: Protest Writings of Nineteenth-Century Maskilim. Compiled from manuscript with an introduction and notes by Shmuel Feiner. Jerusalem: 1988.

Lewin, Judah Leib. “The Questions of Time.” Ha-Shahar 9 (1877): 45–49.

Lilienblum, Moshe Leib. Collected Works. Krakow: 1912.

Lilienblum, Moshe Leib. Letter to Miriam Markel-Mosessohn, 1869. In Collected Works: 1926.

Lilienblum, Moshe Leib. Correspondence with Miriam Markel-Mosessohn. Edited by Abraham Ya’ari, Jerusalem: 1937.

Mendelssohn, Moses. Complete Works. Vol. 19. Stuttgart: Frommann-Holzboog, 1974.

Segal, Taube. “The Hebrew Woman Question.” Ha-Ivri 16 (1879): 69, 77–78, 85, 94, 101–102.

Smolenskin, Perez. “Women Doctors and Midwives in Ancient Times.” Ha-Mabbit 15 (1878): 118–119.

Zederbaum, Alexander. “Completely Free—How?” Ha-Meliz 12 (1872): 17–19; 64–68.

Primary Sources (in English)

Wetzlar, Isaac. The Libes Briv of Isaac Wetzlar. Edited and translated by Morris M. Faierstein. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1996, 92–96.

Rousseau, Jean Jacques. Emile. Translated by Barbara Foxley. London: J.M. Dent, 1993.

Wollstonecraft, Mary. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Edited with introduction by Miriam Brody. London: Penguin, 1992.

Secondary Sources (in Hebrew)

Bartal, Israel. “‘Potency’ and ‘Impotence’: Between Tradition and Haskalah.” In Sexuality and the Family in History, edited by Israel Bartal and Isaiah Gafni, 225–237. Jerusalem: Zalman Shazar Center for Jewish History, 1998.

Cohen, Tova. “Scholarly Technique: The Code of Haskalah Literature.” Jerusalem Studies in Hebrew Literature 13 (1993): 137–168.

Feiner, Shmuel. “The Struggle against False Haskalah and the Boundaries of Jewish Modernization.” In From Vilna to Jerusalem: Studies in the History and Culture of Eastern European Jewry, Presented to Professor Shmuel Werses. Edited by Shmuel Feiner et al., 3–23. Jerusalem: Magnes 2002.

Ibid. “The Modern Jewish Woman: A Test Case in the Relationship between Tradition and the Haskalah.” In Sexuality and the Family in History, edited by Israel Bartal and Isaiah Gafni, 253–268. Jerusalem: Zalman Shazar Center for Jewish History, 1998.

Parush, Iris. Reading Women: The Benefit of Marginality in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society. Tel Aviv: Am Oved, 2001.

Secondary Sources (in English)

Biale, David. Eros and the Jews: From Biblical Israel to Contemporary America. New York: Basic Books, 1992.

Feiner, Shmuel. The Jewish Enlightenment. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003.

Hyman, Paula. Gender and Assimilation in Modern Jewish History: The Roles and Representation of Women. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 1995.

Landes, Joan B. Women and the Public Sphere in the Age of the French Revolution. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1988.

Feiner, Shmuel and David Sorkin, eds. New Perspectives on the Haskalah. London and Portland, OR: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2001.

Magnus, Shulamit. A Woman's Life: Pauline Wengeroff and Memoirs of a Grandmother. London: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2016.

Magnes, Shulamit. “Sins of Youth, Guilt of a Grandmother: M. L. Lilienblum, Pauline Wengeroff, and the Telling of Jewish Modernity in Eastern Europe.” POLIN: Studies in Polish Jewry 18 (2005): 87-120

Magnus, Shulamit and Pauline Wengeroff. Memoirs of a Grandmother: Scenes from the Cultural History of the Jews of Russia in the Nineteenth Century, Stanford: Stanford University Press, Vol.1, 2010, Vol. 2, 2014.