Artists in Britain: 1700-1940

Lilian Holt, Clara Klinghoffer, Gluck, Orovida Pissarro, Flora Lion, Lily Delissa Joseph, and perhaps most famously, Rebecca Solomon were just a few of the trailblazing Jewish female artists in England who overcame many obstacles to work professionally. The chief obstacle for women was the difficulty of obtaining art lessons. In 1906 over one-third of the paintings exhibited at the exhibition of Jewish Art and Antiquities at the Whitechapel Art Gallery were by women, and a year later sixteen Jewish women exhibited at the Summer Royal Academy Exhibition. Although a number of Jewish women worked as artists during the period between 1850 and 1940, most came from wealthy backgrounds. The majority of Jewish women who painted professionally in the nineteenth century were close relatives of male painters.

Introduction

The earliest recorded native Anglo-Jewish artist was Catherine da Costa (1678?–1756), daughter of the physician to Charles II, who studied under the famous drawing master and engraver Bernard Lens and painted portraits of her family and other members of the early Anglo-Jewish community in a charming, though somewhat naive style. Not until a hundred years later did another Jewish woman, Rebecca Solomon, make any impact whatsoever on the English art scene.

From then on the number of Jewish women exhibiting and working professionally increased steadily, so that in 1906 over one-third of the paintings exhibited at the exhibition of Jewish Art and Antiquities at the Whitechapel Art Gallery were by women, while a year later as many as sixteen Jewish women exhibited at the Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy. This was in spite of the fact that Jewish women had to overcome all manner of obstacles to work professionally as artists, not only on account of their sex, but also because they were adopting careers for which there were few precedents in the Anglo-Jewish community, even among the men.

The majority of women who took up painting came from wealthy backgrounds and were probably encouraged to paint and draw by their families, since such skills were considered assets on the marriage market. Indeed, the Royal Family set them a good example, for Queen Charlotte was a serious botanical painter and Queen Victoria an experienced amateur artist.

However, it was painting in watercolour that was primarily taught, oil painting not being considered suitable for a number of reasons. It was far more messy, it left an unpleasant odor, and it could not be carried out in the drawing-room. In addition, more time and serious training were required for a high standard to be reached than with watercolors. Furthermore, oil paintings, tending to be on a far larger scale, necessitated stronger composition, a talent that women were considered to lack. In this way “patriarchal discourses on art divided art practice into the categories of masculine art/feminine accomplishment and masculine professionalism/feminine amateur” (Cherry, 3).

The chief obstacle for women who wanted to become artists was the difficulty of getting art lessons. Women were barred from studying art other than at home with a private drawing master until 1893, when the Female School of Design opened at Somerset House. Even after this, it was hard to study art. One either had to be rich enough to afford the fees of such institutions as the Royal Academy (which opened to women in 1860) or prove that one intended to be a commercial artist. Only then could women enter the schools of design established by the government to train designers. The schools often refused entrance to middle-class women who did not have to support themselves. A further problem was that for many years women were not admitted to life classes, since drawing from the nude was considered outside the codes of respectability and propriety. If they were permitted to draw from the model or from antiques, these were either clothed or covered in draperies.

Rebecca Solomon

The majority of women who painted professionally in the nineteenth century were close relatives of male painters, and Jewish women were no exception. For example Rebecca Solomon (1832–1886) was the sister of the genre painter Abraham Solomon (1823–1862) and the Pre-Raphaelite Simeon Solomon (1840–1905). Their father, Meyer (Michael) Solomon, was a successful hatter who moved on the fringes of fashionable society. The fact that he could afford three of his eight children to study as artists suggests that there were significant funds available, since painting has never been a very secure way to earn one’s keep. While his sons attended the Royal Academy Schools, women were not yet accepted and Rebecca therefore studied at the Spitalfields School of Design.

Rebecca began exhibiting at the age of eighteen and her paintings were shown regularly all around the country, including at the Royal Academy. However, as an unmarried woman, she seems to have been quite dependent on her artist brothers and her career was directly affected by theirs. For many years she lived with Abraham, and since he already had ten years’ experience of the profession when she began exhibiting, she must have relied on his advice considerably.

Abraham had successfully exhibited paintings of period dramas; probably encouraged by this, Rebecca painted a number of works in a similar vein, with titles such as The Arrest of the Deserter and Fugitive Royalists. Her brother, however, was best known for his pairs of pictures showing people in contrasting situations, including First Class—The Meeting, which depicts a rich gentleman and lady meeting in the first-class carriage of a train, and its pair Second Class—The Parting, which shows a widowed mother bidding her son farewell as he prepares to go to sea. Rebecca also painted works in pairs, such as The Industrious Student and The Idle Student, and other works contain a similar contrast within one painting. Examples include The Lion and the Mouse, shown at the Royal Academy in 1865, in which the wealthy old landowner is contrasted both with the poor poacher and his mother, and with the young girl who pleads on the boy’s behalf. It has been assumed that in these works Rebecca was acting under Abraham’s influence, though since both artists produced their first examples of these types of paintings in 1854, it could well have been an idea that they developed together.

When Abraham died in 1862, Rebecca soon moved in with her younger brother Simeon. Although Rebecca had been exhibiting for seven years before her brother’s works were shown in public, many critics simply saw her paintings as substandard works in a style similar to his. Simeon and Rebecca became notorious for their flamboyant life-style and were so publicly linked in the public’s mind that when Simeon was arrested for homosexual offences in 1873, Rebecca also fell from grace. Her works were not exhibited after 1874. Simeon took to alcohol and Rebecca apparently followed suit. She died in 1886 after being knocked over by a tram.

There is little evidence of any Jewish subject matter in the paintings of Rebecca Solomon. It has been suggested that her own personal orthodoxy (she kept a Term used for ritually untainted food according to the laws of Kashrut (Jewish dietary laws).kosher home and observed all the festivals) led her to believe that Jewish ritual was an inappropriate subject for painting.

Lily Delissa Joseph

Self-portrait by English painter Lily Delissa Joseph, observing Shabbat with two candles and her head covered. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Like Rebecca Solomon, Lily Delissa Joseph (1863–1940) was also from a wealthy, cultured family and was also the sibling of a well-known artist. Her brother Solomon J. Solomon (no relation to the previous Solomons) achieved considerable fame and standing and in 1903 was elected a Royal Academician, only the second Jew to gain this honor. Like Abraham and Simeon Solomon, he had studied at the Royal Academy Schools and then in Paris, while his sister studied at the South Kensington School of Art.

Lily Delissa Joseph was certainly a serious artist and exhibited regularly throughout her life at the Royal Academy and other venues. However, this was only one of her interests. She was committed to the fight for women’s suffrage and was a pioneer in many fields, being one of the first women to own and drive her own car and learning to fly aeroplanes when in her late fifties. She was also deeply involved in the community of the Hammersmith Synagogue, where she founded the Ladies’ Guild and was its first President.

As an artist, Lily Delissa Joseph did not suffer from comparisons with her brother in the same way that Rebecca Solomon did. The most important difference was that she married, and thus moved away from the immediate sphere of her family. In her choice of career, she must have been supported by her husband, the architect Delissa Joseph, whom she married in 1887. He was certainly supportive of her other activities, including her struggle for women’s rights, and in 1915 placed the following announcement in the Jewish Chronicle beneath the review of her 1912 exhibition. “We are requested by Mr Delissa Joseph to state that Mrs. Joseph was unable to receive her friends at the Private View of her pictures, as she was detained at Holloway Gaol, on a charge in connection with the Women’s Suffrage Movement” (Jewish Chronicle [JC], 1912). Delissa Joseph’s interest in women’s rights spread to Jewish communal concerns and he was described as an “ardent supporter of the cause of women’s suffrage in synagogue affairs” (JC, 1927).

Lily’s work was also unlikely to be compared or confused with that of her brother, for their styles were very different. This was emphasized at the joint exhibition of their paintings held at the Ben Uri Gallery in 1946, where Lady Swaythling, who opened the exhibition, “pointed out the great difference in their painting although they were not only contemporaries, but also brother and sister. The former, the second Jewish RA, being more conventional in his approach and the latter having an experimental approach” (JC, 1946).

Solomon’s style of painting was very conservative and remained unchanged by modern movements such as Cubism and Fauvism. Towards the end of his life, he painted a number of small works influenced by the Impressionists, but by then fifty years had already passed since the first Impressionist exhibition. In contrast, many of Lily’s works were obviously influenced by Impressionism, but were also described as “experimental,” particularly for the use of “an extremely limited palette” (JC, 1927) of white, cobalt, rose madder, orange madder, and black. An example of this restricted use of color can be found in her Self Portrait with Candles, a rare example of Jewish subject matter in her work.

Self Portrait with Candles is a very striking and memorable piece of work, but it is, in fact, a rare example of a Jewish subject painted by Lily. Delissa Joseph. In 1927, the Jewish Chronicle described her as a painter of “interiors, portraits, family groups and landscapes” and this is borne out by a study of catalogues of her exhibitions and of paintings that she exhibited at the Royal Academy. Only two other works, both Old Testament subjects, could be suggested to be on Jewish themes. However, many of her paintings have not survived, for she destroyed a number herself, either by discarding them, or by ruining them by continually reworking the faces of her models. It has been suggested that it was her deep personal orthodoxy that led to this “curious habit,: inhibiting her from making what could have been viewed as idols. This would explain why Jewish subject matter does not appear more often in her work for she would have considered the religious rituals as inappropriate subjects for representation.

There is of course another reason why both Rebecca Solomon and Lily Delissa Joseph, and indeed their brothers Abraham Solomon and Solomon J. Solomon, did not paint Jewish subject matter. Both sets of siblings came from families that had been in England for some years and were well established in fashionable society. In the 1840s and 1850s when the Solomons were painting, there was a movement towards assimilation to fight antisemitism, in which Jews made great efforts to prove that they made fine and respectable Englishmen and women differing only from Christians in a few observances. The various Solomon painters may have been promoting this view in avoiding religious subject matter in their work.

The problem of antisemitism occurred again in the early years of the twentieth century. It is interesting to note that just a year after the 1905 Aliens Act put a stop to unlimited immigration from Eastern Europe, the Jewish community organised a major exhibition entitled “Jewish Art and Antiquities” at the Whitechapel Art Gallery. The exhibition showed the remarkable contributions that Jews, not only from Britain but also from Europe, were making in the visual arts, but the exhibition catalogue emphasized that Jewish artists were not by any means restricted to painting Jewish subjects. “Some of the figure painters may choose to infuse racial passion into their Jewish subjects, pregnant in their significance and of profound sincerity, but the majority, identifying themselves entirely with their adopted country … show no trace of distinctive thought or differentiation of artistic sentiment. And this, we may be sure, will be the course of the future development – continual assimilation with the single object in this country of advancing the honour and the glory of the British school.” One of Lily Delissa Joseph’s paintings echoed this sentiment entirely. Entitled A Jewish Family it depicted nineteen members of her own family, not one wearing any special clothing or bearing any features that could mark them out as Jewish. Sadly this painting was one of those which met an unfortunate end at the artist’s own hands, and only some of the heads of the sitters are still in existence.

Flora Lion

The Solomon family produced one other woman artist of note. Flora Lion (1876–1958) was a cousin of Solomon and Lily Delissa Joseph, and also came from a wealthy background. She studied first at St. John’s Wood Art School, at the Royal Academy Schools and then at the Académie Julien in Paris. In 1915 she married the journalist and artist Ralph (Rodolphe) Amato, who changed his name to hers rather than vice versa. She was obviously the better known artist of the two, and in one reference book Rodolphe is listed as the husband of Flora, a rare occurrence since it is usually the women who are defined in terms of their relationship to a male painter.

Like Solomon J. Solomon, Flora Lion was a successful portrait painter, and although her style was not unlike his, their relationship was not mentioned by reviewers of her work. She was particularly praised for her strong use of color and love of decorative detail, and the regular appearance of her work at the Royal Academy and Paris Salon brought her many commissions, her preference being paintings of women. Like Solomon, she not only painted many of the most important members of the Jewish community, but also several members of the Royal Family, including Elizabeth, the Queen Mother with her two sisters, the Duchess of Kent and other establishment figures including the wife of Anthony Eden and the wife of Clement Attlee.

It is interesting to note that Flora Lion did not have any children. The demands of being a successful artist combined with raising a family were obviously too great for many women to contemplate. However, this must have been particularly difficult for other members of the Jewish community to accept, since children and the family have always played so central a part in Jewish life.

Orovida Pissarro

An artist who might well have suffered from comparisons with male members of her family was Orovida Pissarro (1893–1968), only daughter of Lucien Pissarro and grand-daughter of Camille. Although it could have been a helpful tool in her career, she decided not to trade on the family name and preferred to be known by and to sign her works simply with her first name.

Orovida showed an early talent for drawing; at the age of five, her drawings were praised by her illustrious grandfather. Orovida began painting with her father and from her uncle she learned to etch, using Camille’s press and tools. She studied for only short periods at art schools and was basically self-taught, referring to her father when necessary.

Orovida, who never married, lived for many years with her parents. It was thus doubly important that she showed work in a different vein to that of her relatives in order to avoid the inevitable comparisons. Indeed, Orovida chose not to continue the family tradition of Impressionism, but instead, inspired by the British Museum’s Chinese Art collection, soon gained a reputation as a painter and etcher of animal subjects imbued with an Orientalism whose novelty attracted a great deal of interest. She painted in tempera on silk, following the Eastern tradition, and experimented a great deal with her etchings, using different kinds of paper, many of them from the Far East. Her favorite subject was the tiger, and her successful depiction of these and other wild animals, and the Mongolian hunters in pursuit of them, was much admired. “An expert of horses has declared that she realized to perfection not only the type of the Tartar horse but also the characteristic seat of the rider, though she had never been out of Europe” (The Times, 1968).

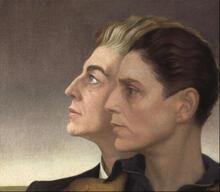

Hannah Gluckstein (Gluck)

Orovida was not the only Jewish woman who shortened her name when pursuing a career in art. Another to do so was Gluck (1895–1978), who was born Hannah Gluckstein. Like the other artists mentioned, she was born into a wealthy family, the only daughter of Joseph Gluckstein, one of the founders of J. Lyons and Co. Her American mother, Francesca Halle, had musical aspirations but had been forced to give these up on her marriage to conform to the conventions of the family into which she had married. Gluck was determined to escape a similar fate and seems to have been convinced that her parents wanted to prevent her becoming an artist. In fact, it appears more likely that what upset them was the fact that she refused to conceal the fact that she was a lesbian.

Gluck, who shared her mother’s talent for music, initially wanted to be a singer but had a sudden change of heart on viewing a photograph of a portrait by Sargent. “There was a great whirl of paint in this, and this hit me in my solar plexus. All thoughts of being a singer vanished. That sensuous whirl of paint told me what I cared for most.” She had already won a number of drawing prizes at school and her parents agreed that she could attend art school. They chose the St. John’s Wood School, which was very near their home.

Gluck did not enjoy her studies there and commented, “As far as I was concerned there was nothing taught that could be considered ‘training.’” She also felt that the teachers took little notice of her because they expected her to marry shortly and give up art altogether. However, considering that the school opened in 1890 specifically to prepare ladies for admittance into the Royal Academy Schools, and that over the years one hundred and sixteen women, including Flora Lion, who was from a very similar background, had gone from there to the RA, this is difficult to believe. In any case, she did have some success there, for in 1913, “at the annual distribution of prizes at St. John’s Wood Art School … Miss Hannah Gluckstein (daughter of Mr. Joseph Gluckstein) … was awarded a prize.” This announcement in the Jewish Chronicle, presumably entered by her proud father, suggests that her parents might not have been as opposed to her career as she suggested.

Nevertheless, she felt stifled and restricted at home, despite the fact that her father offered to build her a studio there, and after a painting trip to Cornwall where she met and was encouraged by two successful women artists, Laura Knight and Dod Procter, she left home in 1915 with little money and no ration card. At this stage, she cropped her hair, began to wear men’s clothing and insisted on being known only as Gluck. Despite this eccentric behavior, her family soon agreed to support her financially. She had a private income, a large house in Hampstead and several members of staff and was therefore able to dedicate herself to her painting.

Gluck is best known for her portraits, her flower paintings inspired by her close relationship with the cookery and flower expert Constance Spry, and a series of works showing scenes from the London stage. These works particularly suited the spirit and fashions of the 1920s and 1930s and Gluck’s eccentricity must also have contributed in some part to the attention that she received. Indeed, after her 1926 exhibition at the Fine Art Society, she was furious that critical attention focused more on her appearance than on her paintings. Nevertheless, at two of her exhibitions all works were sold, and her 1932 exhibition, again at the Fine Art Society, proved particularly popular. It was there that she installed “The Gluck Room” in which she framed all her works in a three-tiered white frame that she later patented, and remodelled the room to echo the design of the frame. The exhibition was extended a month by popular demand, and there was even talk of transferring it to New York.

Gluck professed to be uninterested in commercialism and stated, “I made a vow that I would never prostitute my work and I never have. … Never, never have I attempted to earn my bread at the cost of my work.” In fact, between 1937 and 1973, she painted only intermittently and did not exhibit at all. However, since she did not at all depend upon her painting for her income, this statement loses its daring tone.

These are the Jewish women who made a particular mark in the art world in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but there are indications that many more were studying art and going on to exhibit regularly, both at the Royal Academy and elsewhere. This does not seem to have caused any great outcry in the Jewish community and their submissions to the Royal Academy were regularly referred to in the Jewish Chronicle, where most years the art critic was careful to list all the Jewish participants, even if mention of the women usually came after the men. The early years of the twentieth century produced a particularly high number of Jewish women exhibiting, and this may have been as the result of the 1906 exhibition of Jewish Art and Antiquities held at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, which was a huge success and attracted over 150,000 visitors.

Among the women not so far mentioned who were singled out for praise in the Jewish Chronicle was Mary Raphael, a pupil of Solomon J. Solomon’s who, like him, had studied in Paris and showed regularly at the Royal Academy between 1896 and 1915. For many years she submitted large canvases with subjects taken from the Romantic poets or from Shakespeare, although from 1906 she turned to landscape painting, frequently of French subjects. Like Solomon, she moved in the highest society and Queen Alexandra and Princess Victoria visited her in her studio in 1915.

Amy Drucker

All the artists so far mentioned came from wealthy backgrounds. A study of the other Jewish women known to have participated in Royal Academy exhibitions between 1904 and 1915 reveals that of those who lived in London, all resided in the West End or in North London, and it seems likely that they, too, were not actually dependent on painting to support themselves. Amy Drucker (1873–1951), however, may have been the exception.

Unfortunately, there is very little information available about her early life, so it is difficult to ascertain much concerning her background. What is known is that she studied at Lambeth School of Art, a school intended for artisans who wished to earn a living from art, and it seems likely that she may have been that rare example of a Jewish woman who painted for a living. She painted a number of atmospheric paintings of London life, including scenes from the East End where she was obviously aware of the poverty in which so many Jews lived. The painting she showed at the Whitechapel Exhibition in 1906 had a Jewish subject. Entitled Aliens, it depicted a family of new immigrants to the country and was similar in style and subject to For He Had Great Possessions.

Like Gluck, Drucker must have been a striking figure, for “her fashion in dress was always her own and many will remember the broad-brimmed black hat, the cloak designed for use as a cape and traveling rug and above all the ubiquitous many-colored Mexican bag slung from her left shoulder” (Hansen) She traveled extensively, visiting Palestine, India, China and Abyssinia in search of new subjects to paint, but during both World Wars worked in other fields, serving in the Land Army in World War I and as a factory hand and night watchman in World War II. This all suggests that despite her West End addresses she may have had more humble origins than her fellow exhibitors at the 1906 Whitechapel exhibition.

One thing is very clear. Not one of the women whose work was represented in the 1906 exhibition came from the East End despite the fact that the majority of the Jewish population of London lived there and that some of the best-known Anglo-Jewish artists of the twentieth century, including David Bomberg, Mark Gertler, Isaac Rosenberg and Leon Kossoff, grew up there.

Immigrant Jewish Women

It is perhaps not surprising that more Jewish women from the East End did not become artists, since this area was home to the 125,000 recent immigrants from Eastern Europe, many of whom were pitifully poor. Those women who did work outside the home either helped in family businesses or took on approved jobs, for example as seamstresses, but usually gave up work on marriage. It is unlikely that these families would have had the funds to pay for the studies and materials necessary for an art training; furthermore, the idea of women taking part in life classes would not have been tolerated.

Bomberg, Gertler, and Rosenberg were able to attend the Slade School of Art only thanks to an enlightened organization called the Jewish Educational Aid Society, which was established in 1896 to give grants to Jewish children of promise to enable them to further their studies. The society helped a number of other male artists including Bernard Meninsky and Jacob Kramer, most of whom went to the Slade to study, but had only one application for help from a woman, fifteen-year-old Annie Aaronstein, who had a talent for drawing. However, rather than encouraging her to study to become an artist, they sent her to Goldsmiths’ College for six years, to train to be an art teacher and thus be sure of earning a living.

It is interesting to note that a number of the Jewish artists from immigrant backgrounds who were given the opportunity to study at the Slade became involved with the emergence of the modern movement in England. The fact that few East End women joined their male counterparts at the Slade meant that they did not share this involvement. When, in 1914, David Bomberg organized a Jewish section as part of the Whitechapel Exhibition “Twentieth Century Art—A Review of Modern Movements” and brought over work by Modigliani, Kisling, Nadelman and Pascin, the majority of the British artists selected were those who had received grants from the Jewish Educational Aid Society to study at the Slade, and only one woman was represented. She was Clara Birnberg, a fellow student of Bomberg’s at the Slade.. The work of a similar group of artists was represented in the New English Art Club exhibition in 1913, and this time no Jewish women were included.

Clara Klinghoffer

There was, however, one important female artist who grew up in the East End, Clara Klinghoffer (1900–1970), who was born in Austria but came to England as a small child. After a short stay in Manchester, the family settled in the East End, where Klinghoffer’s father had found work as the manager of a drapery shop. He proved a good businessman, and although they stayed in the East End, they had a house to themselves rather than living in a tenement block.

When Klinghoffer showed a talent for drawing, her mother was determined that she should be able to make something of it and family funds were made available to further her artistic education. Significantly, none of her six sisters trained for a profession, and a special case was made for Clara because her talent was recognized as being extraordinary. She first went to the John Cass Institute in Aldgate, but left early after a teacher made a pass at her. This is the one recorded example of harassment by a teacher of a female pupil, but one imagines that it was not an uncommon problem.

Klinghoffer then went to the Central School, where her work was admired by Meninsky, who commented, “Good Lord, that child draws like da Vinci,” and by Epstein, who called her “a painter of the first order.” From there she went to the Slade for two years and won the admiration of Alfred Wolmark. He recommended her to the Hampstead Gallery, who organized a major exhibition of her work, the first of six exhibitions held in London before World War II. She had a preference for portraits and her early works in particular are a delight. She captured her sitters in seemingly natural poses, demonstrating a wonderful sense of form and mass.

Klinghoffer married a Dutch journalist and in 1930 moved to Holland. She must have had her husband’s support in her career, for she managed to combine painting and exhibiting with raising a family. With the outbreak of war, she and her family moved to New York and from 1946 they divided their time between London and New York. Although Klinghoffer had exhibitions in the United States during the 1950s and 1960s, her work was so different from the Abstract Expressionism which prevailed there at the time that she never really established a name for herself. She obviously found it very difficult to appreciate “the pretentious, yet meaningless abstraction” and, perhaps in defiance, her own work developed very little, becoming slightly too sweet and light on the canvas.

As the century wore on, the number of Jewish women painting professionally appears to have decreased slightly, as did the interest in art in the Jewish community, for further exhibitions of Jewish Art at the Whitechapel in 1923 and in 1927 did not repeat the success of the 1906 exhibition and failed to attract the same number of exhibitors. Clara Klinghoffer was well represented at both these exhibitions, as were a contemporary of hers from the Slade, Mabel Greenberg, and Lena Pillico, the wife of the well-known painter of Jewish genre scenes, Leopold Pilichowski; but few new names appear. Painting and drawing were probably no longer seen as a necessary accomplishment for a wife, and as a result fewer wealthy women were taking up art studies. At the same time, the majority of Anglo-Jewish women now came from families of recent immigrants, where conditions dictated that they learn a practical trade and where they had no time to develop their artistic tendencies.

Lillian Holt

Lilian Holt (1898–1983), for example, the daughter of a civil servant, was interested in painting from an early age and studied at Putney Art School before starting work in an office. She took up painting again at the Regent Street Polytechnic and left a job when the opportunity arose to work for the art dealer Jacob Mendelson. She hoped that there she would learn enough about the art world to be able to follow a painting career herself, and her contract stated that she should be allowed time to paint. Instead, she found herself exploited by Mendelson, although through her work she did meet a number of artists, among them David Bomberg.

They first met in 1923, shortly before Bomberg left for Palestine. When they met again on his return in 1928, they were both on the point of divorce (for Holt had married Mendelson in 1924) and they set up home together and married. Although she had always wanted to paint and was now living with an artist, Holt accepted that her primary role should be to help and encourage Bomberg in his art and that her desire to paint would have to wait. “I had no time to paint while doing the housework and posing for David.” She did not take up painting again until 1945, when Bomberg began teaching at the Borough Polytechnic and, realizing that she had always remained frustrated in her wish to paint, suggested that she join his classes.

From then on, she painted regularly, and when in 1946 a group of his students formed the Borough Group to exhibit under Bomberg’s guidance, Holt was a founder member, exhibiting regularly with them and with the Borough Bottega which succeeded it in 1953. After Bomberg’s death in 1957 Holt continued painting and traveled extensively, visiting isolated sites in Mexico, Morocco, Montenegro, Turkey and Iceland to seek inspiration for her painting. She had her first one-person show in 1971, and her work was purchased for the Tate Gallery in 1980. No doubt other women whose husbands were not painters also put their husbands’ careers before their own.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is noticeable that although a number of Jewish women worked as artists during the period 1850–1940, most came from wealthy backgrounds and did not derive their primary income from painting. Furthermore, several of those women who had successful careers as artists were closely related to male artists who had established a precedent in that field. This suggests that there may have been many other Jewish women unable to fulfill their artistic aspirations due to lack of money, or because their families simply could not contemplate the idea that being a professional artist was a suitable career for a Jewish woman.

Cherry, Deborah. Painting Women: Victorian Women Artists. Rochdale Art Gallery: 1987, 3.

Hanson, P. E. “Memorial Exhibition of the Works of Amy J. Drucker.” Ben Uri Art Gallery: 1952.

Jewish Chronicle Supplement. November 9, 1906.

Jewish Chronicle, January 14, 1927.

Jewish Chronicle, May 17, 1946.

Spielmann, M. H. Jewish Art and Antiquities. Whitechapel Art Gallery. London: 1906.

The Times, August 13, 1968.

First published in 1996 by Lund Humphries Publishers, London. In Rubies and Rebels: Jewish Female Identity in Contemporary British Art.