Haganah

From the founding of the Haganah, the Jewish paramilitary organization in British Mandate Palestine, in 1920, women faced significantly greater obstacles to join the organization than men did. Once a part of the force, they faced pressure from their male leaders and fellow soldiers to perform traditionally feminine activities. Though they fought for more equal opportunity and proved their ability in all parts of the Haganah, women were nevertheless mostly relegated to auxiliary duties such as providing first aid, serving as couriers, cooking, cleaning, and generally serving as motherly figures to the men in combat. Because they were not often at the center of the action, women are frequently overlooked in the Haganah scholarship. But their role in boosting morale and spirit, on top of contributions to combat, was vital to the Haganah’s success.

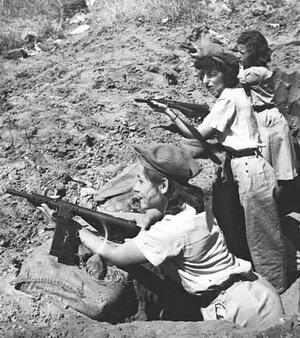

A Haganah officer demonstrates how to fire a STEN gun. Some women in the Haganah served in combat positions, but many more were relegated to "behind the scenes" work of the paramilitary organization, work that was considered more traditionally feminine and appropriate for women. Source: The Haganah Museum, via Wikimedia Commons

Although there has been much academic interest in assorted aspects of the history of the Haganah, the paramilitary organization of the Jewish community in Palestine prior to the establishment of the State of Israel. "Old Yishuv" refers to the Jewish community prior to 1882; "New Yishuv" to that following 1882.Yishuv, the subject of women in that organization has not yet merited an in-depth study, despite the considerable contribution of women in the Haganah during the struggle to establish the State of Israel. The present article is based on interviews conducted with some 30 women from various sectors of the population, who were active in the Haganah. The overall treatment of the various orientations among the women stems from, among other things, the information that emerged from these interviews.

The role of the women members of the Haganah evolved in accordance with the changing nature of the organization as it adapted to the shifting demands of reality. From an emphasis on individual service by selected volunteers, the group metamorphosed into a popular, broad-based organization. The women as well shifted from safeguarding the property and security of local communities to preserving inter-community networks, escorting convoys, and securing transportation routes. The women of the Haganah took part in the struggle against the British Mandatory authorities and the organization of the Lit. "ascent." A "calling up" to the Torah during its reading in the synagogue.Aliyah Bet “illegal” immigration in Palestine and abroad. They joined in the fight against the Germans in World War II and also participated in the War of Independence. They were frequently forced to confront physiological limitations, preconceived notions and human difficulties, for the most part simply because they were women. But they received no special concessions. In order to expand their spheres of activity, they were compelled to convince commanders of their worth, to constantly prove themselves, to display determination and stamina. It was only after strenuous effort and much hardship that they succeeded in carving out new areas for themselves, including those considered to be strictly masculine domains: firefighting; overseeing the secret weapons caches (slikim); engaging in combat, and so forth. It should be noted that even when the women managed to gain a foothold in masculine areas of involvement, they were still obliged to fulfill their traditional roles; their new roles did not come at the expense of the old, but rather in addition to them. Such was the dual function of the women: to hold a rifle or fireman’s hose in one hand, and a pot or broom in the other.

Women’s Obstacles to Joining the Haganah

A small number of women joined the Haganah upon its inception in 1920. It should be noted that women were accepted into the ranks of the Haganah in the same manner as the men. Until late 1924, a commander would recruit members from among his circle of friends and acquaintances. After initial training and a trial period, the members would officially be accepted into the Haganah. During the riots of A seven-day festival to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nissan. Also called the "Festival of Mazzot"; the "Festival of Spring"; Pesah.Passover 1920 in Jerusalem, the few women participating in Haganah operations were nurses at Hadassah who were recruited to provide first aid. Among them was Rosa Cohen, a member and later commander in the Haganah, who was involved in providing first aid to the wounded, evacuating them from the Old City and transferring them to Hadassah Hospital. Testimonies of young women whose membership in the Haganah dates back to the 1920s are few and far between. Only a handful of women (the exact number is unknown) enlisted in the organization during the early years of its existence. The role of the female members at the time was undefined, although they received training in the use of revolvers and in first aid. The women did not group together into a cohesive nucleus but operated individually, each according to her strengths and abilities. One of the rare testimonies of a young woman who joined the Haganah during the 1920s is that of Devora Kirschenbaum, a Haganah member from Jerusalem: “I began to be involved in Haganah affairs during the riots of 1920, when I was a very young girl. At the time we lived in the Beit Yaakov neighborhood, and our house was a ‘point’ (a meeting place for Haganah members) where a few fellows would gather, among them Ze’ev Jabotinsky. They would bring weapons and put them in a hiding place inside our clothes closet. Since I was a Maccabi member, and our home was a ‘point,’ they trusted me and gave me all kinds of assignments” (Avrahami, 198). It seems that initially Kirschenbaum assisted the Haganah without actually becoming a member. It was only later that she was accepted into the organization, apparently after proving herself.

In the early years, the number of Haganah members throughout the country was negligible, largely for reasons of secrecy. In Jerusalem, due to its unique character as a mixed city, the center of the Mandatory administration, and the seat of consuls and legations, clergy, etc., the need to maintain secrecy was even greater. Members were expected to maintain maximum vigilance and be in a constant state of alert; for this reason, Jerusalem was more careful about accepting members in general, and women members in particular. Despite the paucity of female members during the Haganah’s founding stage, there were two women in leadership positions: Rahel Yana’it Ben-Zvi in Jerusalem and Rosa Cohen in Haifa. The policy of including women became official only in October 1924; on the initiative of Rahel Yanait, women members began to be formally inducted into the Jerusalem branch of the Haganah beginning in 1925.

In Tel Aviv in the 1920s women members were accepted only in limited numbers; traditionally, there was one woman for each platoon of men. In general, the sphere of activity for women in the Haganah was a narrow one. The small number of women in the organization in those years can also be traced to the fact that few women worked outside the home; most adult women at the time were homemakers. In late 1925 the number of Haganah members in Tel Aviv was extremely small (roughly 200–300 in total). The members were divided into platoons and the platoons into groups, each of which operated separately. Once a month, a joint operation took place for all members, including the women. The latter were dispersed, each to a different platoon, and served mainly as couriers and liaisons. The number of women Haganah members in Tel Aviv began to rise towards the end of the 1920s.

According to the testimony of Iza Sadeh, in 1927 there were only nine women members of the Haganah in Tel Aviv; in other words, women constituted less than five percent of the local membership (9 out of 200–300). One year later, the number of women had tripled. At the beginning of 1929, there were already 28 women out of 230 Haganah members in Tel Aviv. Hemdah Osio, commander of the women’s platoon in Tel Aviv, was the first woman to participate in a sergeants’ training course; from then on, the courses included a set number of women.

Demanding Inclusion

But women in the Haganah were still forced to fight over the small number of slots allocated to them. In the late 1920s the women of the Haganah demanded a 1:10 membership ratio in proportion to the men; even the right to make up ten percent of the organization entailed a struggle. As Hemdah Osio relates: “Our demand was to set the number of women in the ranks at a ratio of 1:10. After the organizational framework had been put in place, there was no problem at all in expanding the number of women. But here, a long, drawn-out struggle awaited us: raising the number of women members would entail appointing a female officer at the level of platoon commander. This was an audacious step in the dismal days following the Arab pogroms of 1929 … but the women fought for it. This time the struggle took two years, and it was only in 1931, at a special assembly of all the women members, that the commander-in-chief announced … the establishment of a women’s platoon.” In other words, in 1931 the women were granted their demand to make up ten percent of the organization.

At a meeting in October 1924 of the central command on the subject of women in the Haganah, it was determined conclusively that women were essential to the organization; their function, however, remained undefined. Ya’akov Pat, commander of the Haganah in Haifa, wrote in his memoirs: “Following the discussion of the role of the women members in the Haganah, which took place at a meeting of the three city commanders (Jerusalem, Haifa and Tel Aviv), we began to accept women into the ranks” (Eshel, 26). Despite the Haganah’s constitution, there were places in pre-state Palestine, such as Petah Tikvah, where women were still not accepted into the Haganah at this point.

Numerous testimonies and accounts of Haganah members are marked by a recurring theme: the difficulty of being accepted into the organization. If the men faced stumbling blocks, for the women it was twice as hard. Ya’akov Pat spoke of the recruitment of female Haganah members in his city of Haifa: “It must be recalled that we were very demanding in our standards for new women members, much more so than with the men, and we selected the female candidates with great care. For this reason, the level of women members in the organization was high” (ibid., 29). The commanders do not refer in their comments to the reasons for this meticulousness in accepting women members into the Haganah. One can assume, however, that in those years the estimation among commanders and rank-and-file alike (and perhaps also among the women themselves) of the women’s ability to contribute to the organization was so low that an extensive recruitment of women was not deemed necessary. The gender perception of the women’s performance was one of distrust. There was a clear preference for the mobilization of males, although there were a few men who also supported the enlisting of women. Yizhak Sadeh’s favorable views on the inclusion of women in the Haganah and the Palmah can be gathered from his writings, in which women are presented as an integral part of the team going into battle. In an article that appeared in a Palmah newsletter in 1944, he wrote: “We will not be silent nor shall we rest until we have brought word of the Haganah to every girl and woman of the Yishuv. This will raise the level of our defense; it will increase the worth of the Hebrew woman” (Sadeh, 1944). The Arab riots of 1929 and 1936–1939 kindled in many the desire to join the ranks of the Haganah. The arrival of Ya’akov Pat as commander of Jerusalem in 1931 spurred the city’s recovery from the split in the Haganah and the formation of the Irgun Bet (forerunner of the Irgun Zeva’i Le’ummi, or Ezel). Pat began efforts to recruit new men into the Haganah, while Rahel Yana’it attended to the enlistment of women. During this period, many women, most of them young, joined the organization and the women’s areas of involvement were expanded. Upon the outbreak of Arab rioting in 1936, there were already over 200 women members in Jerusalem with training in light arms, signaling and first aid. The Jerusalem women constituted roughly one-tenth of the total membership of the Haganah, which at the time numbered approximately 2,000. By 1937, there were already close to 500 women members in Jerusalem. During the period of the 1936–1939 riots, the proportion of women in the Haganah nationwide surpassed twenty percent, and the numbers continued to rise: in late 1937, out of 24,947 members of the organization 5,487 were women. (It should be noted that the sources refer to an increase in the number of women members, but do not cite the percentage of growth.) Initially, the directive of the Haganah central command (following the aforementioned meeting in 1931 was that the number of women members not exceed ten percent of the total. Since the number of women at the onset of the 1936 riots was small, relative to the tasks assigned to them, it was necessary to immediately recruit more women from various places to meet the shortage; as a result, they were sent to take up their posts without any training or preparation.

Recruiting Youth

A sizeable number of women members joined the Haganah in a circuitous manner, by way of other organizations; from there, it was only a short road to the Haganah. As Zvia Fine recounts: “I joined the Haganah while I was still in Karkur, in 1933. When I moved to Rishon le-Zion, I joined a communications unit of the Haganah. I got my start in a first-aid group. The group was set up as part of Ha-Po’el [sports organization] under the guise of first aid for sporting activities” (Peleg, 733). Other ways of joining the Haganah were through the Civil Guard; through recruitment in schools, for example the Alliance school; and through Elizur, a sports organization for religious young people that operated in a number of cities (girls in the organization also asked to volunteer for patriotic missions).

Another major source of Haganah recruits was Hagam (an acronym for Expanded Physical Education). The idea for the program first took shape at the Reali School in Haifa, on the initiative of the school’s principal, Dr. Arthur Biram. The riots of 1936 prompted an expansion of activities. In 1937 Hagam training became compulsory for girls in the upper grades (until then, only the boys had been required to participate). For the boys, mandatory classes were added in field exercises and other forms of defensive sports. Male and female students at the Reali School took part in guard duty, attended to the wounded and assisted in the work of firemen and auxiliary police. With the help of Reali graduate Ya’akov Dori (the Haganah commander in Haifa and with the establishment of the State the first chief of staff of the Israel Defense Forces), the Reali School unit—consisting of male and female students together with their commanders—was incorporated as a separate platoon within the Haganah. A special program was formulated for the students, their curriculum and activities being determined in consultation with the school. In May 1939, with the massive awakening of the Yishuv in response to the British White Paper, the Zionist General Council of the Yishuv decided, at its session of June 8, 1939, “to implement an expanded program of physical education in all schools, starting with the 1939/40 school year” (Halperin, 246).

In late 1940 the Haganah High Command decided to establish youth battalions also in the form of Field Units (Heil ha-Sadeh, or Hish). The purpose was to absorb young people, both male and female, students and workers, who would receive training in preparation for entering active duty in the Field Units at age eighteen. The Gadna (Hebrew acronym for “youth battalions”) program itself, which had already been in existence since 1936, consisted of units between the ages of fourteen to seventeen where young men and women were trained in communications, signaling, etc.

Acceptance into the Haganah depended largely on personal impressions, but there were also various objective criteria. In the organization’s early days there was a tendency not to accept members under the age of twenty. At a meeting of the city commanders in 1927, it was decided that membership should be limited to those aged eighteen and above and that no more than twenty-five percent of the total membership should be under the age of twenty. This decision was never implemented. Young people always constituted the majority of Haganah members. The primary method of recruitment was through personal acquaintance with the candidate. In the early days of the organization, when there was not yet any formalized acceptance procedure, it was simpler and more convenient to rely on the recommendations of members who had already proven themselves. An additional precondition was the ability of the candidate to adhere to the Haganah’s strict code of secrecy. The candidate’s family background was also a factor; the young woman’s family was observed and its political/underground activities were “graded”; any Communist leanings, even on the part of a relative, were considered a definite shortcoming.

Motivations for joining the Haganah were identification with the nation and the homeland, family norms, social norms, the Arab riots, personal factors and feminine motives.

Profile of the Typical Woman Member

Unmarried Women

Recruitment into the Haganah began at an early age, generally twelve or thirteen. The women usually entered the organization while single, although many of them later married and started a family. The Women Fighters’ Brigade in Haifa, for example, included twelfth-grade girls (Gadna members who had not participated in the training for women recruits on the A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutzim) and those belonging to the Magen David Adom (the Israeli version of the Red Cross) who had learned first aid and were “transferred to weapons training” (Eshel, 97). In Jerusalem, as in the rest of the country, the female members of the Haganah included high school students.

Wives and Mothers

Among the young women of the Haganah there were those who entered the organization already as wives and mothers. Rahel Ben Porat, commander of a group of women in Petah Tikva, relates: “In 1936, I was approached by Eliezer Rubinstein, commander of the Haganah in Petah Tikva at the time, who requested that I organize the female members of Ha-Po’el, whom I had taught as a physical education instructor, to join the Haganah. I liked the idea. I later brought into the Haganah girls from various circles, from nearby neighborhoods and also from Magen David Adom. I myself was included in a co-ed course for group leaders. I engaged in these activities, to which I devoted many days and nights, in addition to my work and while the mother of a young child. …When I returned (from the nationwide course for women members), I recruited new groups of girls” (Oren, 161). This blending of the tasks of wife and mother with those of Haganah member was not unusual in those days. Some of the women in the Haganah were mothers of older children, a fact that freed them to devote more time to their Haganah activities.

Education and Occupations

The members of the Haganah included women from a range of fields. It was not unusual to see secretaries, clerks and manual workers serving alongside women with higher education. In fact, it seems that manual laborers were actually in the majority although, not surprisingly, they left much less in the way of written testimonies than did the better educated members. Given the fact that those who set down their recollections generally represented the upper strata of the female recruits, the image of the woman member of the Haganah that has entered the collective memory is that of an educated woman.

Ethnic Background

Those who enlisted in the Haganah can be divided into various ethnic groups. Most of the women members were of European/Ashkenazi origin, with a minority from long-established Sephardi families. Rahel Tzabari, daughter of a Yemenite family with deep roots in Palestine, was a group leader in the Haganah in Tel Aviv—a fact that her parents tacitly accepted. Likewise, Leah Domarni, a Yemenite girl from the Kerem ha-Temanim quarter in Tel Aviv, whose parents were long-term residents of Palestine and did not object to their daughter’s joining the Haganah. Her father was a well-known laborer and a loyal member of the Histadrut. Leah recalls that there were few Yemenite women in the Haganah, while the Ezel had more. The reason was apparently that the image of the Haganah was of an Ashkenazi, elitist, secular organization; by contrast, the Ezel and Lehi were considered more populist and their ranks included many Descendants of the Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal before the explusion of 1492; primarily Jews of N. Africa, Italy, the Middle East and the Balkans.Sephardim as well as members of religious and even ultra-Orthodox families. Daughters of Sephardi religious families who entered the Haganah met with numerous obstacles. The families did not always look favorably upon their daughter’s activities in a mixed organization that was secular from the outset, in which training exercises were held on the Sabbath and holidays, and basic religious strictures such as The Jewish dietary laws delineating the permissible types of food and methods of their preparation.kashrut and modesty of dress were not observed (the girls wore trousers or shorts).

Religious Women in the Haganah

The integration of religious women in the Haganah was far from simple. The religious authorities were not of one mind on the question of women’s inclusion in the Haganah, although the need for religious rulings on such problematic issues as women’s participation in combat and defense did not prevent the religious-Zionist public from joining the Haganah.

The The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhic (Jewish legal) issues were of less concern to people during this period because of the urgency of the situation: it was a time to act (et la’asot, in religious parlance) and not a time for questions or debate. The need to mobilize was immediate. Consequently, the (religious-Zionist) Mizrachi movement generally tried to refrain from issuing religious rulings on political matters, preferring to shift the onus of decision-making from the religious institutions to the political ones. By contrast, the rabbis of the (ultra-Orthodox) Agudath Israel movement argued that military service was inappropriate for women (the prohibition against women serving in an army does appear in Jewish sources). Nevertheless, the rabbis agreed that in a state of emergency women could be included, although solely in auxiliary service roles. However, since the typical women’s assignments, even within the military framework, did not undermine tradition, religious girls were generally able to find their place in the defense forces during the Yishuv period without harming their faith and customs.

Attitude of Families Toward the Recruitment of Women

As a result of the veil of secrecy, not all parents knew that their daughters were in the Haganah and thus they could not express an opinion. But the attitude of the mothers and fathers to their daughters’ activity in the Haganah was generally supportive, although one can assume that many parents feared for their child’s safety and there may have been some who shared these concerns with their children. In many instances, the parents themselves belonged to the Haganah. But even if they were elderly, or were new immigrants who were unable to actively participate in Haganah activities, they generally supported their daughter’s decision to join—or at least looked the other way. For the most part, those parents who saw the Haganah as a vital endeavor tended to consent to their daughter’s participation; conversely, parents who disapproved of the Haganah were typically opposed to their daughter’s taking an active role. Parents did not always identify with the Haganah’s methods or its principles and it was only natural in such cases that they would attempt to steer their children towards an organization that conformed to their own views. Additionally, the fear (on the part of religious parents) of their daughter’s religious or moral decline may have caused parents to object to her joining the Haganah.

Women’s Roles in the Haganah

Until 1929 the women members nationwide were organized in separate groups without any clearly defined plan. After that date, they continued to provide first aid, serve as couriers, receive weapons training and assist in transporting weapons to their destination—a situation that persisted until World War II. As stated, the entire issue of women’s participation in the Haganah was wrapped in uncertainty. The women gradually worked their way into an active role without any guidelines from Haganah headquarters. In addition to transporting arms and providing first aid, they engaged in assorted domestic tasks and kitchen work to which women were tied “by tradition.” Many of the women members felt that it was their job to send the men out into action and greet them upon their return, in the meantime managing to cook and clean for the exhausted “boys” coming home from the battlefield. This may explain the connection between the image of the women in their own eyes and those of the men—as mothers and caregivers seeing to their every need—and their negligible representation in the senior command posts, even in the spheres of activity in which they constituted the majority.

The women of the Haganah can be divided into two groups: the first (which included the bulk of the women) consisted of those who were satisfied with the auxiliary duties they performed. They internalized the masculine perception that designated them for service roles while simultaneously expecting them to keep up the young men’s spirits and the general morale—a function that the women readily accepted. By serving as mother figures, they instilled a feeling of warmth and hominess in the military camps: they insisted that the men wear clean clothes, made sure to turn down the bed when the men returned from combat, placed a chocolate under their pillow and welcomed the men home from battle with a steaming cup of tea or coffee, a smile and a hot meal. They encouraged the men when they went into battle and when they came back, and helped them return to a state of normalcy, of sanity. The women valued their own work and even if they sometimes felt left out, they believed that their contribution was important.

The second group consisted of the small number of women who did not resign themselves to the traditional roles and who demanded more combat missions. Nyuta Halperin, the commander of the women’s battalion in Tel Aviv, recounted that there were female commanders who were fighters by nature, like Hemdah Osio. Osio argued that the women needed to constantly demand and insist, and not content themselves with being treated nicely by central command or Tel Aviv headquarters. She believed it was necessary to initiate assignments and demand training rather than relying on what was decided for the women by others. In her view, this approach proved effective.

The few women who were not satisfied with service roles were forced to fight for the right to take part in combat. They demanded the right to full participation in all training exercises with all types of weapons, in addition to being included in military operations. In some cases the women fulfilled their goal, proving their worth as fighters and later as commanders. The majority of them passed through all the stages of training, displaying an impressive willpower that helped them overcome the obstacles of the grueling training process. But this was still insufficient to convince their male counterparts that they were suited to be full partners on the battlefield. The fears for their fate should they fall into the hands of the ruthless Arab enemy; the belief of Ben-Gurion, Yisrael Galili and others, that these were the mothers of the next generation; the lack of cooperation on the part of commanders who demeaned their abilities—and perhaps also the masculine need for the glory of victory, the incessant praise for their sacrifice, the constant encouragement of the women—combined to prevent women from realizing themselves in a field where they felt they had much to offer: the battlefield. The exclusion of women from combat roles was frustrating and painful, especially after they had gone through so much training and were in a state of advanced combat readiness.

Even the few women fighters who were “granted” a male assignment—that is, a combat role—understood that their post was only temporary and that when the crisis was over they would return to being ordinary women, with all that that entailed. In time of battle, their womanliness was obscured: their similarity to the male warrior was manifest not only in their outward appearance, i.e., the military uniform, but in their adoption of a lower speaking voice and other male practices. This led to a loss of their feminine identity in the eyes of the men. In general, the women made a point of dressing in a sloppy, careless manner, without fuss or attention to their appearance (another reason for this was that one of their primary functions was to conceal weapons under their clothing). But the women of the Haganah and the Palmah also made use of their femininity when necessary; in fact, this was their primary role in some cases: to be “ordinary” women in the eyes of the British, women who would not be suspected of involvement in questionable activities. True, there were some who disguised themselves as men so as not to be separated from their comrades-in-arms, but this phenomenon was not widespread. On the contrary, most women of the period used their womanliness as a tool for advancing the cause of the Haganah.

Image of the Haganah Woman

In terms of the male assessment of woman’s role, the preference was for women to engage in service rather than combat roles. The men were much more appreciative of a woman who held a cup of tea in her hand than of one who scrambled from peak to peak holding a STEN gun. The presence of women on the battlefield was problematic not only because the members of the Haganah and the Palmah were unenthusiastic about such a move but because of its potential impact on the Arab enemy, who would supposedly be inflamed at the sight of a woman fighter, as Yona Golani, a member of the Palmah, attested. Women were sent into battle at the discretion of the local field commander. Whether or not they made it to the front was determined by their degree of success in convincing the commander that they were worthy and capable of taking part in, and contributing to, the fighting. In the view of the women, the later decision to keep them off the battlefield led to their exclusion from combat tasks and the preservation of their inferior status on the home front, in service occupations. This decision in fact substantiates the assessment that the acceptance of women in combat roles at an earlier point was only a temporary emergency measure.

Devotion to Duty

Many of the women made great efforts to prove that they were physically fit for battle and could carry out all the men’s duties. It was clear to the women that any failure on their part would gradually affect their right to continue their service in the Haganah and Palmah and would prove to the opponents of women’s inclusion in the Haganah that their opinion was justified. For this reason, the women made super-human efforts not to fail or break down. As Hadassah Avigdori relates: “I was the only woman among twenty men and in addition to my weapon I had to drag along a first-aid pack, canteens and a stretcher. … I exert the last of my strength not to fall behind the boys. Rushing up this steep incline is beyond my powers, but I must make sure that no one notices my weakness because afterwards there’ll be talk and complaints about the girls. … Musa politely offers his help, which I decline with exaggerated pride. I must not provide a pretext [for criticism] against the girls.”

“I swear that in the next war married women will not serve—at least not on the same battlefields as their husbands,” Yigal Allon remarked to Rina Dotan, when the latter recounted the difficulties of a woman on the battlefield along with her husband, whose life was in constant danger. His comment proves that there was no unequivocal decision to remove women from the front during the War of Independence. While there was a directive from Ben-Gurion on the subject, it was not always enforced and the matter was frequently subject to the discretion of individual commanders. If the commanders were opposed to women in masculine roles, they would obviously not agree to include women in combat activities. If, on the other hand, they (like Yizhak Sadeh, David Elazar [Dado], Rehavam Ze’evi [“Gandhi”] and others) did not support the approach that women were better off in the kitchen or solely in service occupations—or even if they were simply aware of the desperate need for manpower—the women had a chance of serving in a male role, on the battlefield.

It should be noted that many commanders later underwent a major change of heart on the subject of women’s involvement in combat. The opinion of such commanders as Uri Ben-Ari, Jimmy (Aharon Shemi) and others shifted from one extreme to the other after they witnessed the devotion of the women and their contributions on the battlefield. The decision to totally remove women from the battlefield became an established fact only after the War of Independence. Yigal Allon was unaware when he made his remark that in the next war not only married women but also women in general would not go into battle. Thus the attitude toward women in combat can be reduced to the following principles: Motherhood took priority over security needs; it was just as important as active participation in the war effort because of the lofty goal of survival of the nation. If women were being mobilized in any event (since not all of them were mothers), they were generally directed towards rearguard positions so as to free the men for the battlefield. In times of emergency, there was a greater openness and flexibility regarding the placement of women in masculine positions, in accordance with the opinion of the individual commander.

Conclusion

Did the ideology of equality of the Second Aliyah pioneers find expression in women’s inclusion in the Haganah and the Palmah? The answer to this question is that not only the women of Ha-Shomer (an earlier Jewish self-defense force, founded in 1909) were surprised to discover that the promised equality was only pretty words on paper; the women of the Haganah and the Palmah also came to realize that equality was an important principle—but not a realistic one.

One must, however, be wary of applying the concepts of present-day feminism to the Palmah generation. The very fact that the women were there at the battle positions and command posts, where they combined their traditional roles with combat duties, symbolized, for them, the ideal of equality. The sense of inclusion and camaraderie, of personal contribution to the best of their ability—sometimes to the point of self-sacrifice—gave the women the feeling that they had carried out their mission to the fullest. Even those who held that the equality being offered them was imperfect, and that there existed a gap between reality and the expressed commitment to equality between the sexes, avoided engaging in criticism. Amid the storm of battle and the need for full-scale national involvement, they did not preoccupy themselves with questions of equality and did not protest the traditional roles allocated to them. At the same time, there were individual women who were interested specifically in being included in military operations; when they encountered male opposition, they were left with the bitter taste of the mythical equality.

The psychologist Erik Erikson stated that one of the primary hallmarks of ideology is “The tendency at a given time is to make facts amenable to ideas, and ideas to facts, in order to create a world image convincing enough to support the collective and individual sense of identity” (Hazelton, 22). In other words, although the women proved themselves daily, the men’s opinion regarding the role of women did not change; they continued to believe that women should fill service positions only. And since the bulk of the women engaged in these occupations, they have been neglected by researchers and their contribution virtually ignored by the history books. For since when do people write of the unsung heroes who toil behind the scenes? Nor has much been documented about the women fighters themselves. “People generally speak of the male fighters; the role of the women is not referred to. They were truly few in number—maybe one per division, on average. But perhaps that is why the story of the women fighters has not been told” (Savorai, 116). While the myth of the woman on the battlefield in 1948 is known to every child in Israel, no one can say what they actually did there.

In addition to the fact that history has not devoted much space to such trifles as the service occupations filled by women in the Haganah, the women themselves did not seek publicity. As Nyuta Halperin, commander of the women’s brigade in Tel Aviv, puts it: “We did not know how to make ourselves stand out. In general, the work did not involve earthshaking events, and we were raised on the value of privacy, on the notion that some things are better left unsaid” (Davar, 1984).

But despite their silence, the women’s role in the Haganah was nonetheless not marginal. They took part in all spheres of activity, from transporting and cleaning weapons, giving training courses, tending to the fighters and engaging in active combat when the occasion arose, to the more monotonous tasks of cooking and cleaning, raising morale through song and encouragement and bringing warmth and interest to the dreary routine of the fighters. It was not only a matter of: “How could we forgo anyone who could bear arms?,” as described by the editor of the Palmah Book, Zerubavel Gilad. The importance of the women went beyond their filling the ranks of the Haganah, which were greatly diminished in battle. Their contribution lay in the fact that they brought a different spirit to the Haganah and the Palmah—a spirit of devotion and sacrifice, courage, willingness to fulfill any task, warmth and gentleness, an attentive ear and the desire to prove themselves and excel at everything. There is no question that without the added impact of the women, the defensive force of the Yishuv would not have succeeded in carrying out its missions with the same degree of success, given the complex reality of the times.

The myth of the fighting women of the Palmah persists to this day. As stated, the number of women fighters in the Haganah and the Palmah was actually very small, and for the most part, their fight was for the right to take part in actual combat; as a result, they could not really have participated in all operations. This myth is fed by yet another myth that still exists, namely, the myth of equality between the sexes in the State of Israel. Those who have contributed to the creation of this myth include historians, sociologists, women themselves, the labor movement and so on. In and of itself, the military role of women in the pre-State period was limited; but it was also merely a way station along the road to their true destiny—tending to the next generation. From this standpoint, Israeli culture is no different from other cultures or, as Lilly Rattok put it so well: “What makes [Israeli culture] unique is only the gap between the flaunting of equality and the insistence that women fulfill their patriotic duty in the fighting forces, on the one hand, and their exclusion in reality from the domain in which the myth of the creation of the state was forged” (Rattok, 298). This myth can have great educational value, especially for those young people unfamiliar with the Palmah generation; but we must nonetheless take pains to ensure historical accuracy and keep the myth in perspective.

Avigdori-Avidov, Hadasa. Ba-derekh she-halakhnu (The Path We Walked). Tel Aviv: Ministry of Defense, 1988, 116.

Eshel, Tsadok. Ha-Bahurot ha-hen: sefer havrot ha-Haganah be-Hefah (Those Girls: The Book of Defense Companies in Haifa). Tel Aviv: Ministry of Defense, 1997.

Oren, Benjamin. Their Best Years. Petah Tikvah: 1983, 161.

Peleg, Avraham, editor. Rishonim ba-Haganah (The First Haganah Members). Rishon le-Zion: The Haganah Organization, 1990.

Rattok, Lily. “Women in the War of Independence: Myth and Memory.” In Yom ḳerav ṿe-ʻarbo ṿeha-boḳer shele-moḥorat: yitsugah shel milḥemet ha-ʻatsmaʼut ba-sifrut uva-tarbut ha-ʻIvrit be-Yiśraʼel (Battle Cry and the Morning After: Representations of the War of Independence in Israeli Literature), edited by Hannah Naveh and Oded Menda-Levy. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University, 2002, 298

Sadeh, Yizhak. “The Woman Member in Our Units” (Hebrew). Allon ha-Palmah (February 15, 1944): 2–3

Savorai Gozes, Aya. Palmaha’iyot be-Milhemet Tashah (Women Palmah Members). En-Harod: Ma’arekhet, 1997, 255

Haganah Historical Archives, File 55/59, newspaper clippings, Davar, December 20, 1984.