Bertha Pappenheim

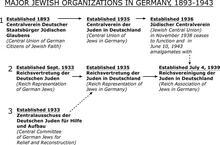

Bertha Pappenheim was the founder of the Jewish feminist movement in Germany. She was committed to both Judaism and feminism, believing that feminism could reinvigorate German Judaism. As a young adult she was Josef Breuer’s patient, and her case was the subject of Sigmund Freud’s writings – her treatment thus marked the beginning of psychoanalysis. In 1902 Pappenheim established a modern social work organization and, based on its success, she founded the League of Jewish Women. Pappenheim believed that male-led Jewish social service societies underestimated the value of women’s work and insisted on a woman’s movement that was equal to and entirely independent of men’s organizations. Pappenheim was also dedicated to the issue of prostitution – she attended all major international conferences on the subject and traveled to Eastern Europe to organize Jewish anti-white slavery committees.

Bertha Pappenheim founded the Jewish feminist movement in 1904 and led it for twenty years, remaining on its board of directors until her death in 1936. She introduced German-Jewish women to beliefs and issues raised by feminism. She spoke openly of Jewish unwed mothers, illegitimate children and prostitutes, and she encouraged Jewish women to demand political, economic and social rights as well as commensurate responsibilities.

Family & Early Life

Pappenheim was born in Vienna on February 27, 1859. Her parents Sigmund (born July 10, 1824 in Prmain essburg, Hungary; died in 1881 in Vienna) and Recha (née Goldschmidt, born in Frankfurt am Main on June 13, 1830; d. 1905) were wealthy, religious Jews. They had three other children: Henriette (1849–1865), Flora (1853–1855) and Wilhelm (1860–). Bertha was always conscious that her parents would have preferred a male child. Years later she wrote that “the old Jews” considered women of secondary importance:

This can already be seen in the different reception given a new citizen of the world. If the father or someone else asked what ‘it’ was after a successful birth, the answer might be either the satisfied report of a boy, or—with pronounced sympathy for the disappointment— ‘Nothing, a girl,’ or ‘Only a girl.’

After her schooling, Pappenheim was supposed to train to become a leisured lady, waiting for the perfect marriage candidate to come by. She led a dull existence, often escaping into daydreams. She did some charity work, which was for her, like for many other girls and housewives of her class and society, the only acceptable diversion besides entertainment, reading, and embroidery. She would later urge other middle-class girls who were bored or unhappy with their meaningless lives to demand vocational preparation and higher education, as well as to pursue social work.

Pappenheim first made history at the age of twenty-one as “Anna O.” Her relationship to Josef Breuer and the later discussions of her case by Sigmund Freud marked the beginning of the psychoanalytic age. Anna O’s treatment with Breuer, her “talking cure,” was the first known psychoanalytic therapeutic alliance. She suffered from disturbances of sight and speech, paralysis, a split personality, the loss of her native language and its replacement with English, hallucinations and suicidal impulses. Breuer hypnotized her and encouraged her to explain how certain symptoms first appeared. As her memories revived, the symptoms disappeared. Patient and doctor shared the discovery of her surprising therapy. She called it “chimney sweeping” or “talking cure” and, with the doctor’s assistance, she actually treated herself. Ernest Jones, Freud’s biographer, considered her the real discoverer of the cathartic method.

Women’s Welfare

After a long convalescence, she moved to Frankfurt in 1889 with her mother. Her entry into Frankfurt social work began with volunteer work in soup kitchens. She quickly gained the experience necessary to organize Women’s Welfare (Weibliche Fürsorge) which she intended as a modern social work organization for women and by women. Although she felt she was fulfilling a religious commandment to help those in need—she spoke of social work as a mitzvah—she shied away from the practices of traditional charity clubs. Instead, she hoped to apply the goals of the German feminist movement, whose literature she read and admired, to Jewish social work. Women’s Welfare serves as an example of one of the most modern Jewish social welfare organizations of the prewar era. Initiated and organized solely by women in 1902 (when other such organizations still had men on their boards), the group envisaged broader programs and cooperated with other organizations in a systematic and comprehensive manner.

Women’s Welfare set up its own day care center for over one hundred infants in 1907 and ran an infant feeding station. It supported its own employment service and Commission to Protect Children. In addition, it initiated international outreach programs to help Jews in Eastern Europe. Its leaders also supported the general women’s movement, attending protest meetings against the establishment of official brothels, and signing petitions to allow women to serve as jurors, to increase women’s citizenship rights, and to raise the requirements for compulsory schooling of girls.

Representing Jewish Women’s Interests

The success of Women’s Welfare (and similar organizations in Hamburg, Munich, Berlin, and elsewhere) encouraged Pappenheim to found the League of Jewish Women (Jüdischer Frauenbund, or JFB) in 1904. League leaders preferred their own organization because Pappenheim believed that the male-led Jewish social service societies underestimated the value of women’s work and trifled with their interest by refusing to admit them as equals. She insisted on a women’s movement that was equal to and entirely independent of men’s organizations. At the inception of the League, Pappenheim’s feminism and her clear anger at men were unflagging: She appealed to women to reach a “certain independence, especially since in most cases...the feelings and understandings of women are more accurate than those of men.” Her suspicion of male-led organizations remained unabated and she rejected an offer from the B’nai B’rith to head its women's auxiliary.

Aware that Protestant and Catholic women had their own national organizations, Pappenheim believed Jewish women also needed a national organization to represent their needs. She turned exclusively to women, convinced that “men always and in every situation follow their private interests.” She expected women to volunteer their services, because Jewish organizations could not afford to pay for the amount of help they needed and because volunteer work would enrich what she saw as the empty lives of middle class Jewish women. She brought the League into the largest middle-class feminist organization, the Federation of German Women’s Associations (Bund deutscher Frauenvereine). Pappenheim credited German feminism with giving “the shy, uncertain advances of Jewish women direction and confidence.”

Pappenheim's commitment to Judaism and to feminism went hand in hand. She argued that feminism could reinvigorate Judaism in Germany, insisting that Jews were turning away from Judaism because women—the transmitters of culture—were alienated from Jewish customs and communities. She did not blame women. Instead, she created the Jewish women’s movement to fight for women’s equality as both a means by which women would return to Judaism and an end in itself. She believed that social work for women within the Jewish community offered a form of practical politics to enhance women’s lives.

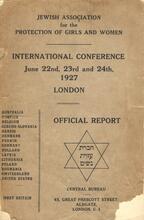

Although Pappenheim devoted her life to the League, she never ceased to do what she called “holy small deeds.” These included ministering to children in the home for unwed mothers that she set up at Neu Isenburg, personally advising its teenage residents, and writing about the tragedy of Jewish prostitution. Pappenheim attended all the major Jewish and secular international conferences on the subject of prostitution and the traffic in women; wrote her best known book, Sisyphus Arbeit (Sisyphus Work), describing the problem of Jewish prostitution and the traffic in women in Eastern Europe and the Middle East; and traveled to Eastern Europe to publicize the dangers of the traffic in women and to organize Jewish anti-white slavery committees. Her campaign blended two major concerns: the status of Jewish women and the fight against antisemitism. She hoped to alleviate the economic and social conditions that pulled Jewish women into the traffic, particularly the need for better education and employment opportunities; expose the Jewish agents responsible for this entrapment; and show the world that Jews were fighting the Jewish portion of this criminality.

Publications & End of Life

Pappenheim’s writings, begun in the 1890s and continued throughout her lifetime, reflected her feminist and Jewish concerns. By 1899, when she published a play entitled Women’s Rights and a translation of Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Women, she was firmly committed to fighting for women’s human rights and their educational advancement. Her pamphlets and books on Jewish life in Eastern Europe expressed her growing alarm at the conditions there. She attempted to mobilize Jewish communities to educate young women and to aid the victims of antisemitic government policies. Her translations (under the pen name of Paul Berthold) and publication of the Ze’enah U-Re’enah (Tsenerene: (1930) a sixteenth century exegetical rendering in Yiddish for women of the Pentateuch, the haftarot, and the Five Scrolls), the Mayse Bukh (1929) (a collection of medieval folk tales, Biblical and Talmudic stories which had been widely read by women), and the seventeenth-century diary of Glückel of Hameln ([1910], a distant relative) can be seen as efforts to retrieve for Jewish women parts of their cultural and historical heritage.

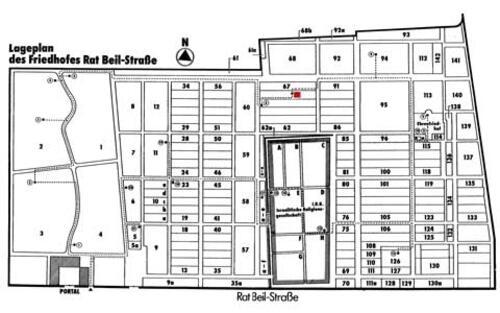

Although Pappenheim retired from the Presidency of the League in 1924, she remained active in it and continued to live at the home for unwed mothers at Neu Isenburg. She was a vigorous opponent of Zionism and of emigration from Germany due to its disruptive effect on family life but in 1935 met with Henrietta Szold to discuss Youth Lit. "ascent." A "calling up" to the Torah during its reading in the synagogue.Aliyah. After the promulgation of the Nuremberg Laws on September 15, 1935 she changed her mind regarding Youth Aliyah. At the age of seventy-six she took several children out of Nazi Germany, delivering them to safety in an orphanage in Glasgow. She died in Isenburg of cancer on May 28, 1936 and was buried in the old Rat Beil-Strasse Jewish cemetery in Frankfurt. In her “last will,” written in 1930, she hoped that people who visited her grave would leave a small stone, “as a quiet promise...to serve the mission of women’s duties and women’s joy...unflinchingly and courageously.”

Selected Works

In the Junk Shop and other Stories. Translated by Renate Latimer. Riverside, CA: Adriane Press, 2008

Kämpfe: Sechs Erzählungen. Frankfurt am Main: Kauffmann, 1916

Sisyphus Arbeit: Reisebriefe aus den Jahren 1911 und 1912. Leipzig: Linder, 1924

Tragische Momente: Drei Lebensbilder. Frankfurt am Main: Kauffmann, 1913.

Guttman, Melinda. The Enigma of Anna O: A Biography of Bertha Pappenheim. New York: Moyer Bell, 2001

Kaplan, Marion. The Jewish Feminist Movement in Germany: The Campaigns of the Jüdischer Frauenbund, 1904–1938. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1979

Konz, Britta. Bertha Pappenheim (1859-1936): Ein Leben für jüdische Tradition und weibliche Emanzipation. Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag, 2005.

Loentz, Elizabeth. Let Me Continue to Speak the Truth: Bertha Pappenheim as Author and Activist. Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 2007

Rosenbaum, Max and Melvin Muroff, eds. Anna O.: Fourteen Contemporary Reinterpretations. New York: The Free Press, 1984.