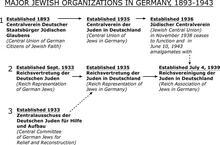

Central Organizations of Jews in Germany (1933-1943)

During the Nazi regime, Jewish leaders established a self-help organization called the Reichsvertretung was established by Jewish leaders. In 1938 the organization was reconstituted as the Reichsvereinigung, and its activities restricted by the Nazi regime. Although leaders of the League of Jewish Women attended its meetings and were close with its president, the League’s formal political participation in the Reichsvertretung was unwelcome by male leaders. In 1936 it was finally given a seat on the Council, but it was dissolved just two years later following Kristallnacht. Some of the League’s prominent members continued to participate in the Reichsvertretung’s important functions. Four eventually created their own special network in order to present a united front for Jewish women’s interests. All four chose to remain in Nazi Germany and continue to serve their community rather than emigrate; all four were eventually deported and murdered.

The Reichsvertretung & The Reichsvereinigung

Establishment of the Reichsvertretung

The Reichsvertretung der Deutschen Juden (Reich Representation of German Jews) was established in September, 1933. Its headquarters were in Berlin-Charlottenburg, on the Kantstrasse. For German Jewry, this was an umbrella organization comprising all the political and religious groups of Jews living in Germany. Its main task was the coordination of Jewish self-help activities during the harsh persecutions of the Nazi era. Jewish self-help activities were widespread, innovative and charitable. Programs were organized to provide whatever legal defenses were still acceptable to the Nazis, as well as to initiate and sponsor a variety of emigration efforts. Alongside these efforts, location of shelter and distribution of food and clothing for the elderly and handicapped, as well as for families suddenly impoverished, traumatized and dispirited was an ever-escalating responsibility.

The Reichsvertretung also served as the political representative of German Jewry. From 1939 on it was the only organization attempting to meet all the various needs of German Jews. Throughout its existence from 1933 to June 1943, its structure and tasks were constantly being reorganized.

Reconstitution as the Reichsvereinigung

In 1938 the members of the Reichsvertretung planned its reconstitution, one of the main goals being a more effective centralization of executive functions. In February 1939, efforts to restructure as a response to ever-changing and growing needs and desperation led to a “new” organization under a different name: The Reich Association of Jews in Germany (Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland).

On July 4, 1939, the legal status of the Reichsvereinigung was determined by a special directive from the Nazi regime. The Reichsvereinigung included all Jewish subjects of the Nazi Reich as defined by the Nuremberg Laws (1935) and not by religion. Thereafter, the government-approved tasks of the Central Organization were limited to the coordination and support of the emigration of Jewish people, the organization of basic and vocational education (the only approved schooling for Jews) and the distribution of welfare. The Reichsvereinigung was supervised by the Ministry of the Interior, (i.e. the Reich Security Main Office, RSHA), section IV B 4, headed by Adolf Eichmann.

The Role of the Reichsvereinigung after Deportations

The beginning of deportations to concentration camps in October 1941 brought a fundamental redirection of purpose to the Reichsvereinigung, which was forced by the Nazi government to help organize the deportations. It became the duty of the Jewish leadership to notify people who were to be deported. Any support or supply of necessary goods to people gathered at assembly points and about to be deported was left to the Reichsvereinigung. The “forced” collaboration of the Jewish community at this point was the subject of controversial discussion after the war.

In June 1943 the headquarters of the Reichsvereinigung in Berlin were summarily closed by the RSHA and the remaining staff deported to Theresienstadt. It was replaced by the “Rest-Reichsvereinigung” (Residue Reich Association), which existed until shortly before the fall of the Reich. It dealt mainly with Jews living in mixed marriages and their descendants, who were not being deported. It continued its restricted and controlled work within the Jewish hospital in the Iranische Strasse in Berlin until liberation, in May 1945. There were 285 Jewish women and men living in the hospital during the summer of 1943. This figure stands in stark contrast to the numbers of Jewish women and men living in Germany prior to January 1933, when there were more than 520,000, of whom approximately 170,000 lived in Berlin.

Within the Central Organization of Jews in Germany, especially between 1933 and 1938, in addition to the stress and urgency of a continually worsening situation for all Jews in Germany, there was a complicated hierarchy of leadership and power between women and the male leaders of the organization.

The League of Jewish Women and the Central Organization: 1933 to 1938

When the Jewish leadership negotiated the founding of a central organization of German Jews in the fall of 1933, Hannah Karminski (1897–1942), who was the secretary of the League of Jewish Women, participated in the meetings. Karminski was the “soul” of the League, succeeding Bertha Pappenheim, who had retired from her activities in the League.

Relationship between the League and Leo Baeck

Held in high esteem in the Jewish community, Hannah Karminski personified the women’s interests represented by the League of Jewish Women. During this time she became a close friend of Leo Baeck (1873–1956), who was one of the spiritual leaders of German Jewry and the president of the Reichsvertretung from 1933 until his deportation to Theresienstadt in January 1943. In 1939, when Hannah Karminski had a leadership position in the department of welfare, they became even closer. Their offices were side by side in the Kantstrasse and they had daily work meetings, often spending their private time together as well.

Leo Baeck was also close to the president of the League of Jewish Women, Ottilie Schönewald, and other members of the League, including Margarete Berent. He was frequently invited to speak at the annual meetings of the League. Although President Baeck and the Reichsvertretung thought highly of the work and activities of the League of Jewish Women, those same women did not have a seat or a vote in the Reichsvertretung. Between 1933 and its liquidation following the pogrom of November 9 and 10, 1938 (“Kristallnacht”), the women of the League led a campaign to become full members of the Reichsvertretung but failed in the attempt for a variety of reasons.

First, though the president of the Reichsvertretung, Leo Baeck, was sympathetic to women’s politics, the atmosphere in Jewish organizations and communities was patriarchal. Jewish women had no right to vote in the conservative Jewish communities. Their political participation was not welcome. Even when the League was part of the Jewish Self-Help and participated wholly in the attempt to survive as a community under Nazi persecution and violence, all power and influence remained in men’s hands.

The League is Given a Seat on the Council

It was only in 1936 that the League was given a seat on the Council of the Reichsvertretung. Although Hannah Karminski and Cora Berliner had attended the organization’s meetings from 1933 on, the League officially became a member only in 1936. Prior to this date, the League could propose a delegate, but the Council was not obligated to accept their suggestions. Instead they chose women who would promote their political interests and strategies. In 1936, for example, the women of the League proposed the chairwoman, Ottilie Schönewald, for this position, but the Reichsvertretung instead appointed Bertha Fraenkel-Ehrentreu (1895–1965), who was a Zionist and a member of the Orthodox denomination, both of which were underrepresented in the organization. Clearly, male power was far more important than women’s interests.

The League of Jewish Women was dissolved after the November pogrom in 1938. Some women continued their work, trying to fight for women’s issues within the Central Organization. Cora Berliner and Hannah Karminski, for example, advocated for women’s participation in the Reichsvereinigung while they continued their activities for and among women in the Women’s Self-Help. Primarily they supported the education and especially the emigration of women and girls.

After Kristallnacht

The pogroms of November 9 and 10, 1938 were called Kristallnacht (the Night of Broken Glass), because broken glass from damaged houses, shops and synagogues littered the streets of almost every German city or town. The Hitler Youth and the SS destroyed Jewish institutions and private homes and arrested more than thirty thousand Jewish men, among them leaders of the Reichsvertretung. Shortly after Kristallnacht, the offices of the organization were closed for approximately two weeks.

The Role of Cora Berliner

During this time, the members of the organization held meetings in private homes. Some of them took place in Cora Berliner’s apartment in Berlin. She had been hired by the organization in October 1933, and thereafter held important positions. She was responsible for reports on the economic situation of German Jews that were used by the organization for several protest pamphlets presented to the German government. She also worked in the public relations department, of which she became the head. In 1939 she headed the departments of women’s emigration, statistics and public relations. In March 1940, Cora Berliner became an unofficial member of the board and was allowed to participate in confidential meetings.

Other Prominent Women in the Reichsvereinigung

Her colleagues and friends, Hannah Karminski and Paula Fürst (1894–1942), also attended meetings of the board. Hannah Karminski co-managed the welfare department, while Paula Fürst was head of the school department. Hildegard Böhme (1884–1943) and Käte Rosenheim (1892–1980) were also prominent in the organization, Böhme being one of the few women to head a district office of the organization. (District offices were responsible for the administration of services to smaller Jewish communities.) Käte Rosenheim was the director of the Kinderauswanderung (Children’s Emigration) department from 1934 until her own emigration to the United States of America in 1940. Together with her colleagues, she helped more than 7,200 Jewish children to escape Nazi Germany.

Although Cora Berliner was a member of the board and Hannah Karminski and Paula Fürst joined the board meetings of the organization, the three women earned lower salaries than their male colleagues—only 350 RM per month as compared to the men’s 625 RM for virtually the same work. While leaders such as Leo Baeck often praised the women’s work, it was never suggested that they should have the same rank and the same pay as their male colleagues.

Perhaps this was one of the reasons why Cora Berliner, Hildegard Böhme, Paula Fürst and Hannah Karminski developed a special form of networking, creating a group of four, with a special purpose: to present a strong and united front to promote Jewish women’s interests.

The Group of Four

The integration of the lives of these four women was remarkable. They not only worked together in the offices of the organization in Kantstrasse; they also lived together. Cora Berliner shared an apartment with Hildegard Böhme. Paula Fürst was the partner of Hannah Karminski, and they too shared an apartment. These women had similar backgrounds; they were educated and had teaching experience. They had known each other through their work before 1939 or from their activities for the League of Jewish Women.

The four spent almost all their private time together. On religious holidays they would go to the synagogue to hear Leo Baeck preach. There was a bond of affection and purpose among them, a special form of women’s networking and connection. Their lives contrasted with the daily lives of their male colleagues, who were married and lived with their families. Great calamity brought these women together in a voluntary association. Studies of women in the far more extreme conditions of concentration and labor camps have also revealed the development of forms of communication and additional survival strategies unique to women. The persecuted women often built small family units in which they helped each other to survive. The four women built their family within the Reichsvereinigung of Jews in Germany.

Relationship of the Group of Four with Leaders of the Reichsvereinigung

Nevertheless, every woman in this group of four also maintained a warm relationship with one of the leading male members of the organization. Hannah Karminski was very close to Leo Baeck, the president; they were both deeply religious and this created a special connection between the two. Paula Fürst and Hildegard Böhme were particularly fond of Moritz Henschel (1879–1947), who was on the board of the Reichsvereinigung and, at the same time, the president of the Jewish Community of Berlin. After Leo Baeck was deported to Theresienstadt at the beginning of 1943, Moritz Henschel became the president of the Reichsvereinigung.

Cora Berliner was a trusted friend and confidant of Otto Hirsch (1885–1941), a lawyer who had become secretary of the Reichsvertretung in September 1933. In 1941 he was arrested and murdered in the Mauthausen concentration camp because of his protest against the early mass deportations of Jews from Stettin and Baden in the fall of 1940. His death was a shock for his colleagues because it was obvious that the Nazi regime would punish protests or resistance with both imprisonment and execution. After his death, Cora Berliner cared for Hirsch’s wife, Martha Hirsch (1891–1943/44), spending time with her and supporting her in her unsuccessful attempt to flee Nazi Germany. In 1943, Martha Hirsch was deported to Auschwitz, where she perished.

Conflict Within the Group

Certainly the group of four were not without their conflicts. Though we have little documentation of quarrels, there is one letter from Cora Berliner, written after her fiftieth birthday in 1940, in which she wrote to her friend Hans Schäffer (1886–1967) that this birthday had been the most exhausting day she had ever experienced in her whole life. She had received sympathy and recognition for her work, but also “jealousy from her close female colleagues.” Possibly the conflict started with an article written by Otto Hirsch and printed in the Jüdisches Nachrichtenblatt (Jewish Newsletter, 1938–1943), at that time the only Jewish newspaper. In an article about Cora Berliner, Hirsch acknowledged her longtime significance for the League of Jewish Women. This must have disappointed Hannah Karminski, who had been the “soul” of the League and its most active member.

Fate of the Group of Four & the Male Leaders of the Reichsvereinigung

Although all four these women had various opportunities to escape Nazi Germany, they chose to stay in Germany and not to leave the Jewish community. They paid for this decision with their lives. In June 1942 Cora Berliner and Paula Fürst were deported to the East, leaving Hannah Karminski alone in her apartment for several months. In November 1942 Hannah Karminski was arrested and deported to Auschwitz a few weeks later. Hildegard Böhme had tried in vain to go in place of her friend and colleague. She herself was deported to Auschwitz in May 1943 and murdered there, sharing the fate of her friends and colleagues.

Only Leo Baeck and Moritz Henschel survived the Shoah. The other leading male members of the Reichsvereinigung perished in concentration camps. It is tragic that these talented, industrious and generous Jewish women and men lost their struggle to survive Nazi persecution in their native land. Their enemies simply held too much power and gloried in its brutal exercise, with no regard for innocence or human justice.

Adler-Rudel, Salomon. Selbsthilfe unter dem Nazi-Regime 1933–1939 im Spiegel der Berichte der Reichsvertretung der Juden in Deutschland. Tübingen: Mohr, 1974.

Alexander, Kurt. “Die Reichsvertretung der deutschen Juden.” In Festschrift zum 80. Geburtstag von Rabbiner Dr. Leo Baeck am 23. Mai 1953, 76–84. London: Der Council, 1953.

Ball-Kaduri, Kurt Jacob. “Von der ‘Reichsvertretung’ zur ‘Reichsvereinigung.’” In Zeitschrift für die Geschichte der Juden I, 191-199. Tel Aviv: Olamenu, 1964.

Barkai, Avraham and Paul Mendes-Flohr. Deutsch-Jüdische Geschichte in der Neuzeit, Vol. 4: Aufbruch und Zerstörung 1918 bis 1945, 249-271, 330-338. München: Beck C.H., 1997.

Brodnitz, Friedrich S. “Memories of the Reichsvertretung. A Personal Report.” In Leo Baeck Institute Year Book 31, 267-277. N.p.: Secker and Warburg, 1986.

Esh, Shaul. “The Establishment of the Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland.” In Yad Vashem Studies 7, (1968) 19-38.

Fabian, Hans Erich. “Die letzte Etappe. I. Die Reichsvereinigung, II. Theresienstadt.” In Festschrift zum 80. Geburtstag von Rabbiner Leo Baeck am 23. Mai 1953, 85-97. London: Council for the Protection of the Rights and Interests of Jews from Germany, 1953.

Fabian, Hans Erich. “Zur Entstehung der Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland.” In Gegenwart im Rückblick, edited by H. A. Strauss and K. Grossmann, 165–179. Heidelberg: L. Stiehm, 1970.

Gruenewald, Max. “The Beginning of the Reichsvertretung. In Leo Baeck Year Book 1 (1956): 57–67.

Ibid. “Der Anfang der Reichsvertretung.” In Deutsches Judentum. Aufstieg und Krise. Gestalten, Ideen, Werke, edited by Robert Weltsch, 315–325. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1963.

Hahn, Hugo. “Die Gründung der Reichsvertretung.” In In zwei Welten, edited by H. Tramer, 97-105. Tel Aviv: N.p., 1962.

Hildesheimer, Esriel. The Central Organization of the German Jews in the Years 1933–1945: Its legal and political status and its position in the Jewish community. Jerusalem: N.p., 1982.

Ibid. Jüdische Selbstverwaltung unter dem NS-Regime. Der Existenzkampf der Reichsvertretung und Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1994.

Jüdisches Nachrichtenblatt (Berlin, Germany: 1938–1942). Berlin: Verlag Jüdische Rundschau, 1938-1942.

Kulka, Otto Dov. “The Reichsvereinigung of the Jews in Germany.” In Patterns of Jewish Leadership in Nazi Europe 1933–1945, Proceedings of the Third Yad Vashem International Conference, 45–58. Jerusalem: Vad Vashem, April 1977.

Ibid. “The Reichsvereinigung and the Fate of German Jews 1938/1939–1943: Continuity or Discontinuity in German-Jewish History in the Third Reich.” In Juden im Nationalsozialistischen Deutschland, edited by Arnold Paucker, 353-363. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1986.

Ibid, ed. Deutsches Judentum unter dem Nationalsozialismus. Dokumente zur Geschichte der Reichsvertretung der deutschen Juden 1933 bis 1939, Vol. I, Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1997.

Ibid. Hildesheimer, Esriel. “The Central Organisation of Jews in the Third Reich and its Archives.” In Year Book of the Leo Baeck Institute, 34 (1989): 187–201.

Maierhof, Gudrun. Selbstbehauptung im Chaos. Frauen in der jüdischen Selbsthilfe 1933–1943. Frankfurt/New York: Campus Verlag, 2002.

Margaliot, Abraham. “The Dispute over the Leadership of Germany Jews 1933–1938.” In Yad Vashem Studies 10 (1974): 129–148.

Meyer, Beate. “Gratwanderung zwischen Verantwortung und Verstrickung: Die Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland und die Jüdische Gemeinde zu Berlin 1938–1945.” In Meyer, Beate and Hermann Simon. Juden in Berlin 1938 bis 1945. Begleitband zur gleichnamigen Ausstellung in der Stiftung Neue Synagoge Berlin. Centrum Judaicum, 291-337. Berlin: Philo, 2000.

Plum, Günther. “Deutsche Juden oder Juden in Deutschland.” In Die Juden in Deutschland 1933 – 1945, edited by Wolfgang Benz, 35–74. München: N.p., 1989.

Archives

Bundesarchiv, Berlin: Files Reichsvereinigung. Centrum Judaicum Archives, Berlin: Collection Reichsvereinigung.

Zentrum für Antisemitismusforschung an der Technischen Universität Berlin, Bibliothek: Arbeitsberichte des Zentralausschusses der deutschen Juden für Hilfe und Aufbau bzw. der Reichsvertretung der Juden in Deutschland 1933 bis 1938.

Leo Baeck Institute, New York: Collection Reichsvertretung/Reichsvereinigung.

Yad Vashem Archives, Jerusalem: Ball-Kaduri-Collection; Collection Kulka/Hildesheimer.